Cantray and Kilravock: The early medieval place-names of Strathnairn

In which I consider what these names might tell us about early medieval settlement along a stretch of the River Nairn

(With many thanks to Chris Callow, Murray Cook, Clare Downham, Alan G. James, Daniel Maclean, Roddie MacLennan, Simon MacLennan, Peadar Morgan, Michael S. Newton, and Victoria Thompson for their help.)

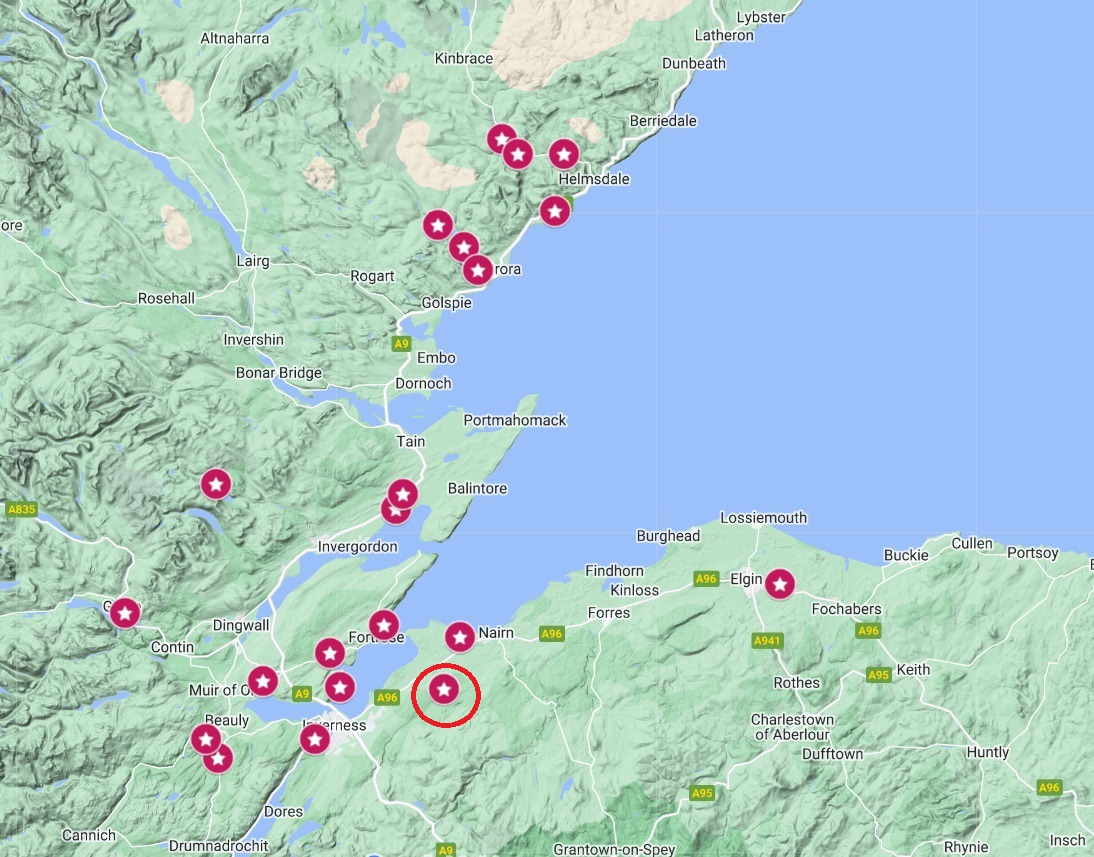

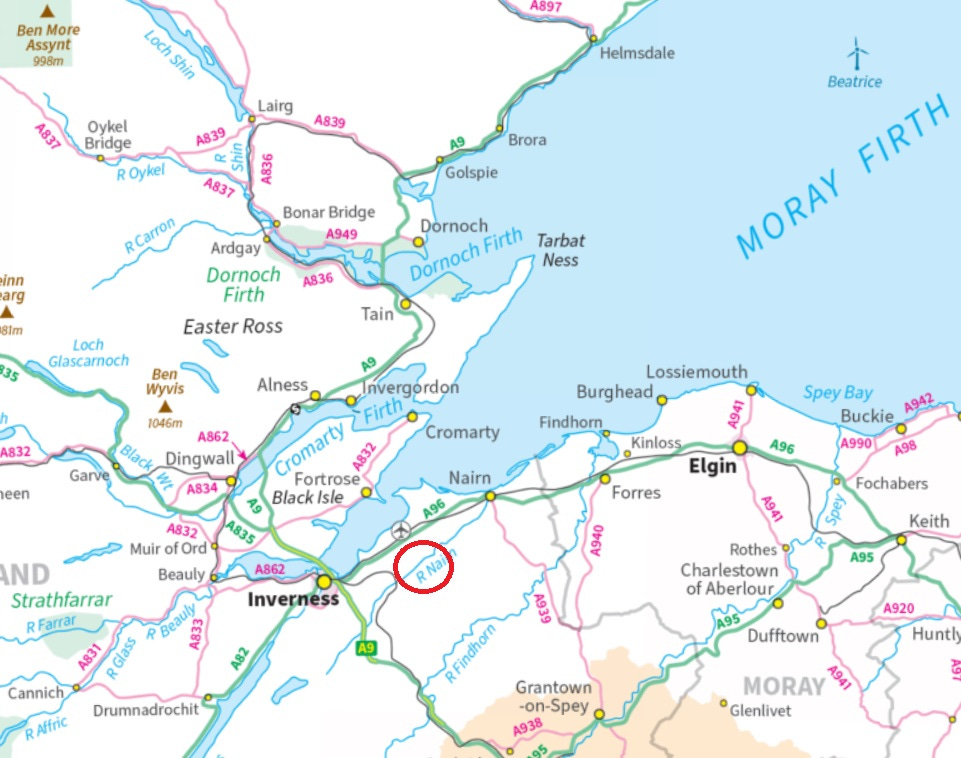

Hello, and welcome! You join me as I’m getting stuck into my PhD research into the early medieval Moray Firthlands, with a particular focus on Nairnshire.

One strand of my research relates to place-names of Nairnshire that have survived from the early medieval period (c.500–1000 AD).

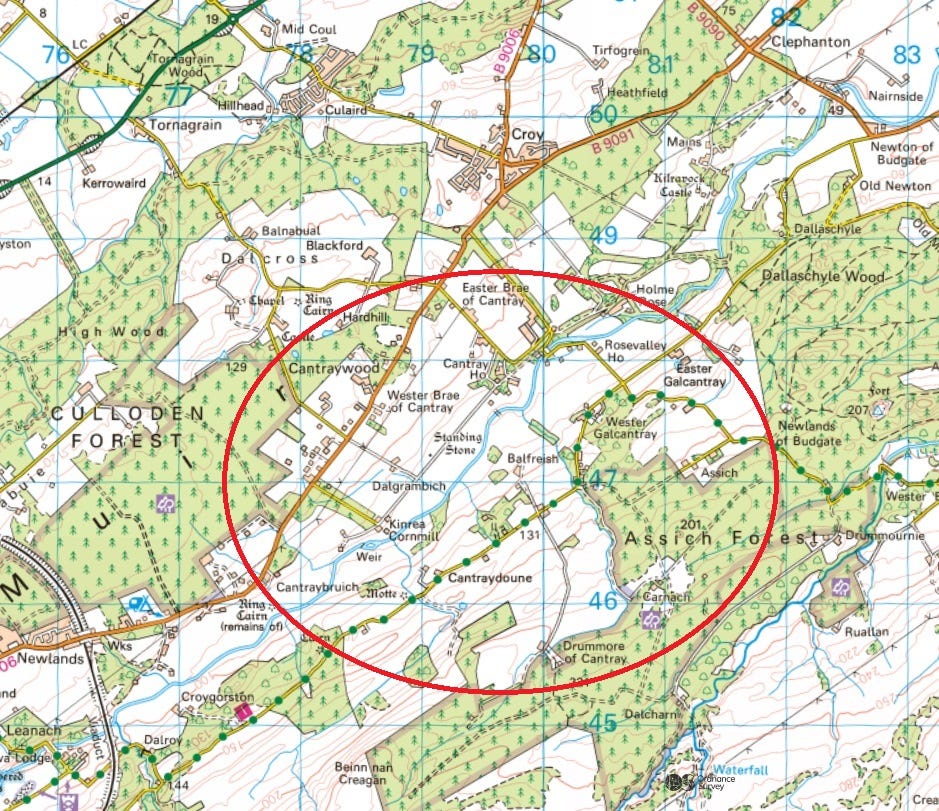

There’s one particular cluster of names that I’d been meaning to look into for a while. They lie along a c. 3km stretch of the River Nairn, roughly between Kilravock Castle and the Clava Cairns.

They come in various forms and were clearly coined at different times (as we’ll see), but they all share a common element: Cantray, pronounced ‘Cantra.’

A clue to Pictish settlement patterns?

My hunch was that this name was a survival from the Pictish era (c. 300–900 AD), and thus one that had persisted through the language shifts in the area from Pictish to Gaelic and from Gaelic to Scots and English.

Given that ‘Cantray’ names occur on both sides of the river, I also thought they might be evidence of early territorial organisation based on river valleys.

While researching my MA dissertation I’d come across examples from Anglo-Saxon England, like the Rodings in Essex, about which Tom Williamson wrote:

The parishes’ shared name indicates an earlier, tribal origin for this territory, as the land of Hroða’s people. The eight parishes lay either side of the River Roding, extending up to the watersheds on either side.

It’s hard to discern similar early territories in the Moray Firthlands, because Pictish population-group names don’t seem to have survived in place-names in this region. In their absence, I thought the Cantray names offered the most promising avenue for exploration.

So I dug into it, and as always, I wrote this blog as I went along, not knowing where I’d end up.

An early Celtic place-name element: trebo

My first port of call for place-name research is always William J. Watson’s The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland, first published in 1926 and still the go-to reference work.

Watson interpreted the second syllable of ‘Cantray’ as:

An early Celtic ‘trebo-‘, ‘settlement,’ perhaps also ‘village’.

He went on to explain that:

In Welsh, tref is a homestead, hamlet; technically in the Welsh laws it was a division consisting of four ‘gauels,’ each of 64 acres, and four trefs made a ‘maynaul’; cantref is the largest division of land in a lordship or dominion, a ‘hundred’.

Indeed the similarity of Cantray to cantref had often made me think it might be what we’re seeing here in Strathnairn: a Pictish unit of land division similar to a Welsh cantref or Anglo-Saxon hundred.

But Watson didn’t think so, because regarding Cantray specifically, he wrote:

This is probably for an early canto-treb-, ‘white stead’.

So not a cantref or hundred, but a ‘white’ (in the sense of ‘shining’) settlement or village.

A surviving Pictish name?

But at least it seemed like I was dealing with an ancient name. When Watson says ‘early,’ he means the Common Celtic language ancestral to both Pictish and Gaelic, as well as Welsh, Irish, Cornish, Manx and Breton.

Since Pictish preceded Gaelic in this part of Scotland, it seemed that Watson’s canto-treb might belong to a time when Pictish, or its immediate ancestor, Common Brittonic, was spoken in Strathnairn. That might be as long ago as the late Iron Age.

Technically, the name could have arrived in the area with Gaelic, and the word order, with the specific (canto) preceding the generic (treb), might initially suggest that. In other Brittonic languages, the word order tends to be the other way around.

Here where I live in Cornwall, for example, I’m surrounded by place-names where treb is the first element: Tremough, Treliever, Treluswell, etc.

However, another great place-name scholar, W.F.H. Nicolaisen, noted that treb is a rare element in Gaelic, and that the reverse word order is quite common in Pictish Scotland:

There is in the north-east, a considerable number of names in which tref is preceded by the specific, unless it is assumed that they contain the Gaelic cognate treabh (evidenced in no more than a couple of Irish place-names) rather than [Brittonic] tref.

As well as Cantray, Nicolaisen cites Menstrie, Clenterty, Fintray and Fortray as examples of treb places where the specific (adjective) precedes the generic (noun).

‘canto’ – a word for a portion of land?

Armed with the near-certainty that I was looking at a really early name, I turned my attention to the specific element, canto.

Watson had interpreted this as ‘white’ or ‘shining,’ but it turned out that this is one of the rare occasions when later toponymists disagree, and see it instead as a demarcation of land.

It’s the word underlying the county name of Kent, for example. The Romans called Kent Cantium, about which Rivet and Smith in The Place-Names of Roman Britain wrote:

For Cantium, [Kenneth] Jackson suggests a variety of possible meanings: ‘encircled (seagirt) land,’ ‘land on the periphery,’ ‘borderland,’ or ‘land of hosts’.

Rivet and Smith preferred the first of these for Kent in particular, arguing that:

Jackson’s first meaning, ‘corner land, land on the edge,’ or similar, seems most natural.

Alan James, in his survey of Brittonic place-name elements in north Britain, also took up the idea of ‘corner land,’ and suggested it might mean a piece of land of a particular shape:

In the Celtic languages, *canto- has the senses of ‘a circumference, a boundary’ and ‘a division, a share of land’. Both roots have contributed to semantic developments between and across languages. In south-east English dialects, the sense ‘a portion of land’ seems to have been carried over from late British, but in northern place-names the reference seems to be generally to ‘a corner, an oblique angle,’ though it may also indicate ‘a triangular piece of land’ or even ‘a sloping edge’.

The idea of canto as a portion of land appealed to me, because the name element ‘Cantray’ did seem to be used that way in Strathnairn.

I was aware of the names Cantraybruich, for example, which (with help from the Gaelic speakers in the Scottish Place-Names Facebook group) I understood to mean ‘Cantray of the embankment,’ and Cantraydoune, meaning ‘Cantray of the motte’.

In these names it seems to behave like the well-known Pictish word element pett, or the Gaelic dabhach (Scots davoch), both of which mean a portion of land. There are no pett or dabhach names in this part of Strathnairn, and I wondered if ‘cantray’ might be standing in for them.

With this in mind I started to look at how the name had been used in the past, to see if it might offer any clues.

Cantray in medieval charters

The first place I looked was the medieval charters of neighbouring Kilravock Castle. These are discussed in the book A Genealogical Deduction of the Family of Rose of Kilravock, written in 1684 by Hew Rose, continued in 1753 by Lachlan Shaw, and edited by Cosmo Innes in 1848.

These charters threw up five Cantray names, in chronological order of appearance:

Cantrafreskyn: A lost 13th-century charter recorded a grant of the land of ‘Cantra freskyn’ by Marjorie de Moravia to her daughter Isobel. Its extent is not known, but the de Moravia family were big landholders in Strathnairn in the central Middle Ages.

Cantrabundie: A charter of 1364 records a dowry to Joneta Chisholm from her father Robert, lord of Urquhart Castle on Loch Ness, of “the ten-mark land of Cantrabundie,” on her marriage to Hugh Rose of Kilravock. I don’t know what the ‘bundie’ element might refer to, although I believe bun is Gaelic for ‘bottom or foot of’. (Any suggestions gratefully received!)

Little Cantray: A charter of 1420 records the grant of Cantrabundie, Little Cantray and Ochterurchill to John Rose of Kilravock from his great-uncle John Chisholm. This may be a renewal of the 1364 charter above, since most of the Kilravock charters were destroyed in 1390 when Alexander Stewart, earl of Buchan (better known as the Wolf of Badenoch), set fire to Elgin Cathedral where they were kept.

Galcantree: A charter of 1458 shows a William of Doles (Dallas in Moray) as holder of the lands of Mikilbudwete (Budgate) and Galcantree (Galcantray) on the east side of the river. I don’t know what the ‘gal’ element here means, although since this is its first textual appearance, it’s unlikely to be Old Irish gaill, vikings or foreigners. (Again, any thoughts gratefully received!)

[UPDATE 30/11/24: Very many thanks to Peadar Morgan, who has drawn my attention in the comments to his 2013 PhD thesis on Scottish place-names that contain references to ethnic groups. He wrote on p. 251 regarding Galcantray that:

The model Gall + existing name… existed in Ireland, where in 1605 Balligalantrim (1565 Ballygallantry), IrG n.m. baile + Gall-Aontroim, applied to that part of the town of Antrim, IrG Aontroim, which was inhabited by the English.

As we saw above, the earliest landholding family on record for Cantray is that of Freskin ‘de Moravia,’ a Flemish aristocrat implanted into the Laich of Moray by David I circa 1150. There is a Loch Flemington around three miles north-east of Cantray, and Galcantray may be another indicator of Flemish settlement in medieval Nairnshire.]

Cantra: A charter of 1493 shows another William of Dallas as the holder of ‘Cantra,’ presumably the estate now centred on Cantray House (see ‘Kantradallash’ below).

Cantray- names in 1590

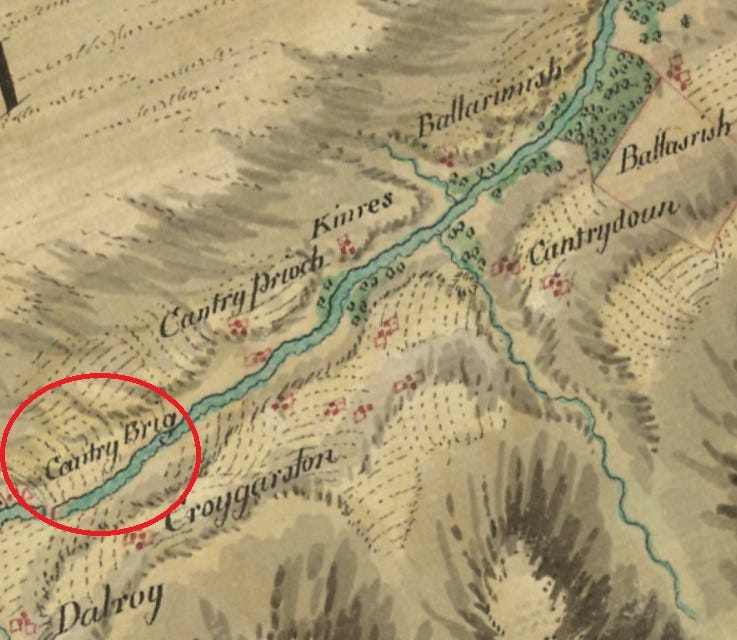

Moving to the earliest map of the area, Timothy Pont’s map of Moray made in around 1590, there are five ‘Cantra’ (or, as he has it, ‘Kantra’) names along both sides of the river.

They comprise:

Kantradallash: This is shown as a castle, and seems to correspond to the estate mentioned above, centred on the current Cantray House. Its name has been updated since its appearance in 1493 as ‘Cantra’ to incorporate the name of the landholding family of Dallas.

Kantrafrish: This is likely the farm now known as Balfreish, on the east side of the river. Alan G. James has suggested to me on Facebook that ‘frish’ may be:

phris, the genitive of preas, ‘bush, thicket’, cognate with P-Celtic pre:s.

If so, Kantrafrish consists of three Pictish/Brittonic (P-Celtic) elements: cant (plot of land), treb (stead or settlement) and pres (thicket). Ordinarily this might mean something like “plot of the farmstead of the thicket,” but since cantra appears to be operating as a single element, seemingly to denote a portion of land, it might just mean “portion of the thicket.”

Kantraprisaish: Pont shows this as adjacent to Kantrafrish, but he wasn’t always correct and this may be Kantrafrish again. If not, my nearly-non-existent Gaelic suggests that ‘prisaish’ may mean something like ‘thicket-y’, describing a place perhaps abounding in gorse. If anyone has any more informed suggestions I would be very happy to hear them!

Kantradoun: This is Cantraydoune, a name still in use. The ‘doune’ refers to an artificial mound that sits on the property that is usually thought to be the remnants of a Norman castle motte. (I think it may (also) be an earlier moot-hill, but there’s no space to go into that here.)

Cantra na karn: This, on the west side of the river, means ‘Cantra of the cairn,’ presumably referring to the chambered cairn at NH 77793 45949. This may be the same place as the extant Cantraybruich, since on a map of c. 1645, ‘Cantra na karn’ has gone and ‘Cantra Bruach’ has appeared.

Cantra in the 18th century

On General Roy’s military map of Scotland, drawn up between 1747 and 1755 in the wake of the 1745 Jacobite rising, one new Cantray name appears alongside ‘Cantry’ (Cantray), ‘Gallachantry’ (Galcantray), ‘Cantrydoun’ (Cantraydoune) and ‘Cantry Prioch’ (Cantraybruich):

Cantry Brig: At the south-western limit of the ‘Cantray’ names, Roy shows a bridge next to a small fermtoun, with the name Cantry Brig (Cantray Bridge). On later maps ‘Cantry Brig’ is shown as ‘Cantray Beg’ (Little Cantray) and it is still known as Little Cantray today. Indeed it’s likely that Cantry Brig/Cantray Beg was the ‘Little Cantray’ cited in the 1420 charter noted above.

Modern Cantray names

The coining of names with ‘Cantray’ has continued into modern times, with the addition of Scots, English and hybrid names of:

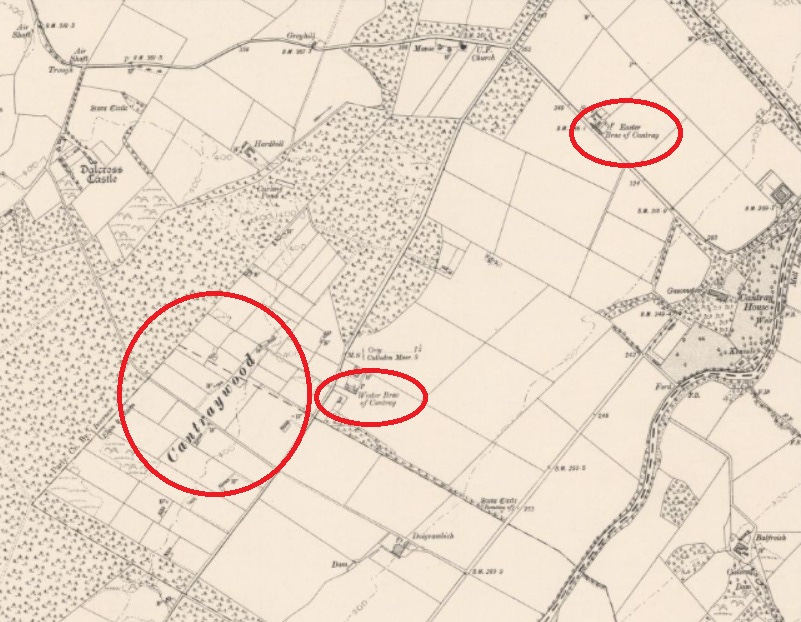

Easter and Wester Brae of Cantray: These two hamlets, halfway up the hillside on the west side of the River Nairn, first appear on the Ordnance Survey six-inch map of 1869.

Drummore of Cantray: This farm, on the ‘big ridge of Cantray,’ as its name implies, overlooks the river from the top of the eastern hillside, and also first appears on the 1869 OS map.

Cantraywood: This name first appears on the 1903 six-inch OS map. It looks like new farmland at that time, carved out of woods and waste along the top of the western ridge above the river.

The names come to a stop at the top of the ridges either side of the river, suggesting that ‘Cantray’ is, and always has been, confined to the valley of the Nairn.

A Pictish settlement in Strathnairn?

So I’ve established that the name element ‘Cantray’ goes back as far as textual and cartographical records will take us—to the thirteenth century.

But as I noted at the start, its underlying elements canto + treb suggest that it dates from much earlier—to Pictish or even Iron Age times.

In particular, the treb element seems to refer to a stead or settlement. So is there a Pictish settlement in the area that it could have originated with?

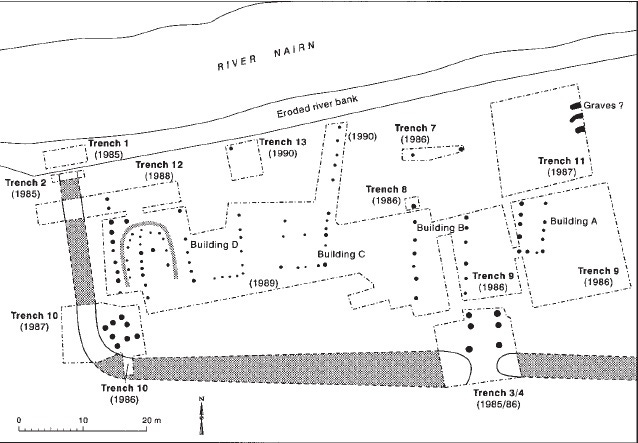

In fact there is evidence of a sizeable ancient settlement in Cantray. Cropmarks identified in 1984 revealed a large rectangular enclosure with an entrance gate, severely truncated by river erosion, standing on a terrace beside the river just north of Easter Galcantray farm.

The site was first identified in an aerial survey conducted by Professor Barri Jones and local aviator and archaeologist Ian Keillar. It revealed many previously-unidentified cropmarks along the southern Moray Firth littoral, including similar rectangular-shaped enclosures at Thomshill near Elgin, Balnageith near Forres and Tarradale near Dingwall.

A Roman camp of the Agricolan period?

Their rectangular shape and regular spacing led Jones to think, reasonably enough, that these were temporary Roman camps; vestiges of Agricola’s military campaign in the north that culminated in the battle of (the still unsatisfactorily-identified) Mons Graupius in 83 AD.

Between 1985 and 1990 Jones spent several seasons excavating the site at Easter Galcantray, producing an interim progress report in 1986 in which he concluded that:

The space available for this site in its form prior to the major river erosion of 1829 would have allowed the presence of a site of up to five acres, standing on a spur overlooking both the course of the Nairn and the spate channel to the south.

Jones sadly died before he could fully write up his findings, but in 2002 Dr Richard Gregory agreed to produce a summary and critique of Jones’s notes and interim reports for the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Why Easter Galcantray may not be a Roman camp

Jones’s proposal that this was an Agricolan camp was based on three main findings: the V-shaped ditch of the main enclosure; a single radiocarbon date of AD 80–220; and the layout of buildings inside the enclosure—including what Jones perceived to be evidence of a timber gate, corner tower and rectangular barracks.

In his critique of Jones’s notes, however, Gregory noted that alternative interpretations can be made of all of these pieces of evidence. Of the V-shaped ditch, he wrote:

Although V-shaped defensive ditches were undoubtedly used by the Roman army, it is a form which is also found on a number of Iron Age sites in Scotland.

The single radiocarbon date also came in for some criticism:

[The date] is not, in itself, conclusive evidence that the site was occupied and abandoned during the late first century. Still less is it conclusive evidence that it was occupied and abandoned by the Roman military, particularly since no late first-century Roman pottery was recovered from this feature or from elsewhere on the site.

Gregory argued that an alternative explanation could also be found for the internal structure that Jones proposed was a tower:

At the nearby site of Tarradale, located at the head of the Beauly Firth, a comparable corner tower arrangement was also found associated with a large ditched enclosure. In this instance, however, artefactual evidence suggests that this putative tower dates to the middle centuries of the first millennium and was associated with a large native site.

Like Tarradale, then, Gregory felt that the enclosure at Easter Galcantray could have been a native Pictish site rather than a temporary Roman camp.

The find of a single dark blue bead (below) at Galcantray may add weight to this idea. It’s similar to a ‘Roman bi-conical’ bead found this year at The Cairns, an Iron Age broch site in Orkney currently being excavated by Martin Carruthers. (There’s no space to say more about this, but the similarity is intriguing!)

If Gregory was correct in this assumption, could the enclosure be the original treb (‘settlement’) of the Cantray place-names?

Was the rectangular enclosure the treb of canto-treb?

Strangely, neither Jones nor Gregory seem to have made that connection. This must be partly because Jones was convinced that the site was Roman, and partly because Gregory seems to have taken at face value a rather perplexing claim by Jones that:

The root of the name Galcantray was probably derived from the Irish Gaelic for the ‘place of two streams’.

As we’ve seen, however, ‘cantray’ is almost certainly not Gaelic but Pictish or Brittonic canto-treb. While treb almost certainly means settlement, translations of canto range from the discredited ‘white, shining’ to notions like circumference, boundary, angle, corner and triangular piece of land.

One possible interpretation of canto-treb might be “the settlement on the triangular piece of land.” In fact Jones did see the enclosure as sitting on a spur between the River Nairn and a second spate channel; a piece of land which might be thought of as triangular, or at least pointy.

Another possibility I’m mulling, given that this settlement was enclosed by a rectangular ditch, is that the canto, in its sense of boundary or circumference, refers to this type of enclosure. I don’t have any firm ideas on this at the moment—as always, any thoughts are most welcome.

Did early medieval Cantray have a church?

One striking thing about Cantray is that, despite seemingly being a cohesive geographical unit stretching back into the early Middle Ages, at first glance it doesn’t seem to have a place of Christian worship.

The oldest known ecclesiastical sites in the area are the fourteenth-century church at Barevan, over the ridge to the east, and the medieval chapel of Dalcross, over the ridge to the west.

However, Kilravock, a medieval castle on the river just downstream of Cantray, is one of an intriguing cluster of names in Inverness-shire and Easter Ross that start with the Gaelic element cill-, meaning church (below).

Indeed Lachlan Shaw, editor of the Kilravock charters, noted in 1753 that:

The name of Kilravock indicates the cell or chapel dedicated to some now forgotten saint; and tradition points, alas! to the present pigeon-house as the site of that chapel.

This exact spot seems unlikely, however, as the dovecote (or doocot) at Kilravock is built into the side of a slope, unusual for an early medieval church in this part of the world.

The National Monuments Record of Scotland file on the doocot notes that:

There is no trace or local knowledge of the chapel mentioned by Shaw.

However a chapel there certainly was, as a charter of 1363 confirms that the chaplain of Dalcross was to come and preach in the chapel of Kilravock twice a week.

A seventh- or eighth-century church site?

Indeed the Kil- prefix suggests that this chapel had a pedigree far more ancient than the castle itself. Simon Taylor sees cill- names in this part of the world as locations of churches founded in the late seventh or early eighth century, perhaps dependent on the monastery at Rosemarkie.

He and others also see them as indicators of a first wave of Gaelicisation in the area, with churchmen coming from Iona and other Gaelic monasteries to establish outposts among the Picts.

If Taylor is correct and these cill- names are signifiers of early Gaelic churches in Pictland, it’s possible to imagine that one such church was founded at Kilravock, adjacent to the enclosed Pictish settlement at Cantray. Its clerics were perhaps even tasked with converting the local inhabitants to the new faith, or at least with ensuring they didn’t lapse from their faith when things got tough.

This of course can only be speculation. Apart from the place-name, there’s no evidence of an early church at Kilravock, and the jury is still not decided on whether the enclosure at Galcantray is a Roman camp or a Pictish/Iron Age settlement.

But if the scenario above is correct, then what we may have in this part of Strathnairn is evidence of an early encounter between indigenous Picts and incoming Gaels, preserved in place-names that have persisted for centuries.

Conclusion: Evidence of proto-historic settlement in Strathnairn

This investigation hasn’t ended as neatly as I would like. I’m still not sure exactly what the name ‘cantray’ signifies, or why it has been used for centuries in this particular valley as a word for a portion of land.

But I am reasonably confident that it is ancient (Pictish or late Iron Age) and confined to the valley, and therefore that it might be evidence of early territorial organisation based on river systems.

It’s also turned out to be far more productive as a place-name element than I thought, being used in at least 15 place-names in this part of Strathnairn since 1200.

And I’m very tempted by the possibility that the original canto-treb was the big enclosure at Easter Galcantray, and that neighbouring Kilravock was originally a Gaelic church tasked with administering pastoral care to its inhabitants, and perhaps even converting them.

If you have any thoughts, I’d be very glad to hear them!

References

Richard Gregory, Excavations by the late GDB Jones and CM Daniels along the Moray Firth littoral, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 131 (2002)

Alan G. James, The Brittonic Language in the Old North: A Guide to the Place-Name Evidence (updated 2024)

G.D.B. Jones, Ian Keillar and K. Maude, Excavations at Cawdor 1986 (1986)

Ailig Peadar Morgan, Ethnonyms in the place-names of Scotland and the Border counties of England, PhD thesis, University of St Andrews (2013)

W.F.H. Nicolaisen, Scottish Place-Names: Their Study and Significance (1976)

A.L.F. Rivet and Colin Smith, The Place-Names of Roman Britain (1979)

Hew Rose and Lachlan Shaw, A Genealogical Deduction of the Family of Rose of Kilravock, edited by Cosmo Innes. (1848)

Simon Taylor, Place-names and the early church in Eastern Scotland, in Scotland in Dark Age Britain, edited by Barbara Crawford (1996)

W.J. Watson, The History of the Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (1926)

Tom Williamson, Environment, Society and Landscape in Early Medieval England (2013)

All names Gall formed much (too much) of my PhD thesis. Canna entice the thesis to download onto the tablet (too many Goill?), but did get its database to open, with this below. Happy to accept the Roman reference should read Pictish, especially with the evidence from Tarradale (just down the hill from me). I see I had also taken Watson at his word, albeit leaving options open. (Copy & paste has lost the italicisation.)

Galcantray CRD-INV ‡ (Croy & Dalcross). Antiquarian name. Ch. 20 Goill: probable.

NH810480 (SS). +Easter, +Nether†, +Newlands, +Over†, +Wester.

Farms (OSnb 18:17,20). Newlands – a house (OSnb 18:22).

1618 Nr/O.Galcantray (Retours no. 36)

1636×52 Gald Cantray (Gordon Map 5)

1755 Gallachantry (Roy Map)

1873 E/W.Galcantray (OSnb 18:17,20)

1873 Newlands of Galcantray (OSnb 18:22)

1920 ScG "galla-chantdra" (Diack MS Nairn, 18)

1894×1926 ScG "Gall-channtra· Gall(a)-channtra" {MS 360, 4} (Robertson MSS)

1894×1926 ScG "Gall(a)channtra" {MS 364, 132} (Robertson MSS)

attrib. ScG n.m. Gall + lenited ScG ex nom. *Canntra (BrB adj. can + BrB n.f. treβ)

ScG Gall-Channtra – 'subdivision of Cantray ('white settlement') associated with the

Goill'

Easter Galcantry (between Wester Galcantray and Newlands of Galcantray) provides the

grid reference. Galcantray is on the south side of the River Nairn as it crosses the former

parish border with Cawdor NAI, giving a borderland context. However, an apparent

Roman enclosure with ramparts was excavated at NH810483 in the 1980s (where tradition

had placed a graveyard or chapel) (Canmore, 15033). The ethnonym ScG n.m. Gall is

probably an antiquarian reference to this pre-Gaelic feature, prefixed to the established

name for the district, Galtray, which in turn may have referred to the colour of stone

construction. (Alternatively, Cantray could be BrB n.m. cant + BrB n.f. treβ, 'district or

border settlement', or BrB *cantref 'lordship division'.) The name Cantray is in Gaelic

Cantra or Canntra (Watson 1930, 8)

excellent as always!