In search of the 10th century at the National Museum of Scotland

A visit to see Scotland’s early medieval treasures doesn’t go as well as I’d hoped.

Of all the things I’m doing to prepare for the MA I’m starting in September, a visit to the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh was high on my priority list.

It has an outstanding collection of early medieval treasures, gathered – not always without local resistance – from around Scotland.

Since 2008, generous funding from the Glenmorangie whisky company has allowed NMS curators and research fellows to mount exhibitions, commission photography, give lectures, and produce a trio of gorgeous books – all interpreting the complex c. 600-year period between the departure of the Romans from Britain in 410 AD and the rise of Scotland as a medieval European kingdom.

So when I realised we’d have a free afternoon in Edinburgh on our way home to Cornwall from Nairnshire, there was only one thing I wanted to do.

In search of the tenth century in Edinburgh

I thought a visit to the NMS would help me to make sense of the period, especially the bit I’m planning to focus on for my MA dissertation: the tenth century.

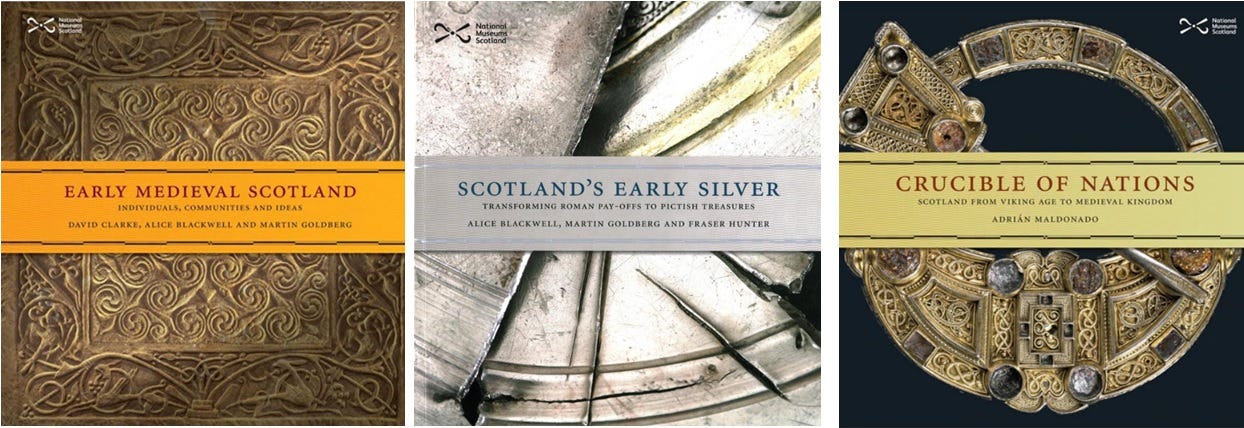

It’s an extremely murky time, but a pivotal one in the history of Scotland – a time when Pictish-speaking provincial kings gave way to a Gaelic-speaking royal dynasty, and Scotland began to coalesce into a single nation, forged under pressure from Norse raiders and settlers from the north and west, and Anglo-Saxon imperial ambitions from the south.

(This is a massive oversimplification, btw – ‘Scotland’ in the late first millennium AD was a hot mess of conflicting ambitions and influences, see map below for a sample.)

Early People or Kingdom of the Scots?

Reader, this is not quite how things turned out.

For a start, my chosen period falls somewhat between two stools as far as the NMS is concerned.

One gallery, called Early People, is organised around cultural themes and practices spanning a vast tract of time – from the neolithic period to the widespread adoption of Christianity in the eighth and ninth centuries: some 9,000 years of prehistory and proto-history.

A second gallery, Kingdom of the Scots, picks up the thread and charts the rise and fall of Scotland as an independent kingdom – a c. 600-year period encompassing the Davidian Revolution, the Wars of Independence, the Declaration of Arbroath, the Union of the Crowns and the 1707 Acts of Union.

The tenth century, though, seems to fall into a bit of a no-man’s-land between these two collections.

It’s not part of the proto-historic ‘Pictish’ era with its enigmatic symbol stones, intricate cross-slabs and immense silver chains. But neither is it quite part of the historical medieval era, whose charters, seals and manuscripts open a window on to Scottish culture, society and politics from the 12th century onwards.

Early People: 9,000 years of human endeavour

Practically speaking, that meant I didn’t really know where to look for the tenth century in the NMS. I tried Early People, but soon became overwhelmed by the sheer volume of stuff on display – 9,000 years is a long time!

The museum has also grouped objects thematically (e.g. metalworking, food preparation) rather than chronologically, usually pointing out where they were found but not when they were made.

That’s great for creating a sense of cultural continuity and progression, but not so great for someone looking for a snapshot of a particular point in time.

As a (very) fledgling historian with a bent towards archaeology, I get the downsides of periodisation: human activity doesn’t fall neatly into discrete time periods, and archaeological evidence is often at odds with what historians say was happening in a given era. (Martin Carver’s paper on the real-world complexity of ‘Anglo-Saxon’ society and culture, What Were They Thinking, is really good on this.)

Too much to take in at once

So the thematic grouping makes perfect sense, but the net effect for me was mostly disorientation. I realised I didn’t know what I was looking for, I hadn’t done any preparation, and I wasn’t ready for such a huge assault on the senses.

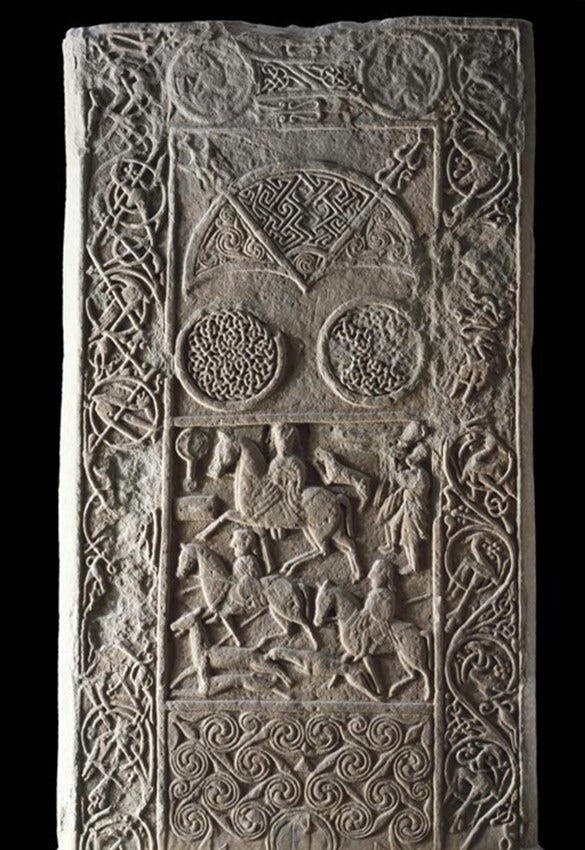

I’ve spent the best part of a year obsessively reading about early medieval Scotland, and to come face to face with objects I’ve read about hundreds of times – the Monymusk reliquary, the Hilton of Cadboll stone, the Whitecleugh chain – was more overwhelming than illuminating.

And as someone who has intense battles with anxiety and sensory overload, and who’s spent the last two pandemic years working alone and barely leaving the confines of one tiny Cornish town, suddenly finding myself in a massive museum full of sights, sounds and people was a bit too much.

(Plus I had a husband and two kids in tow, who were – understandably – much more interested in robots and animals than in old stones with crosses carved into them.)

A peek into Kingdom of the Scots

All this meant that, by the time I realised I wasn’t going to find the tenth century in Early People, I didn’t feel mentally up to embarking on Kingdom of the Scots.

The rest of the family had returned from the robot zone and 13 year old daughter was keen to head to Forbidden Planet, so we didn’t have much time in any case.

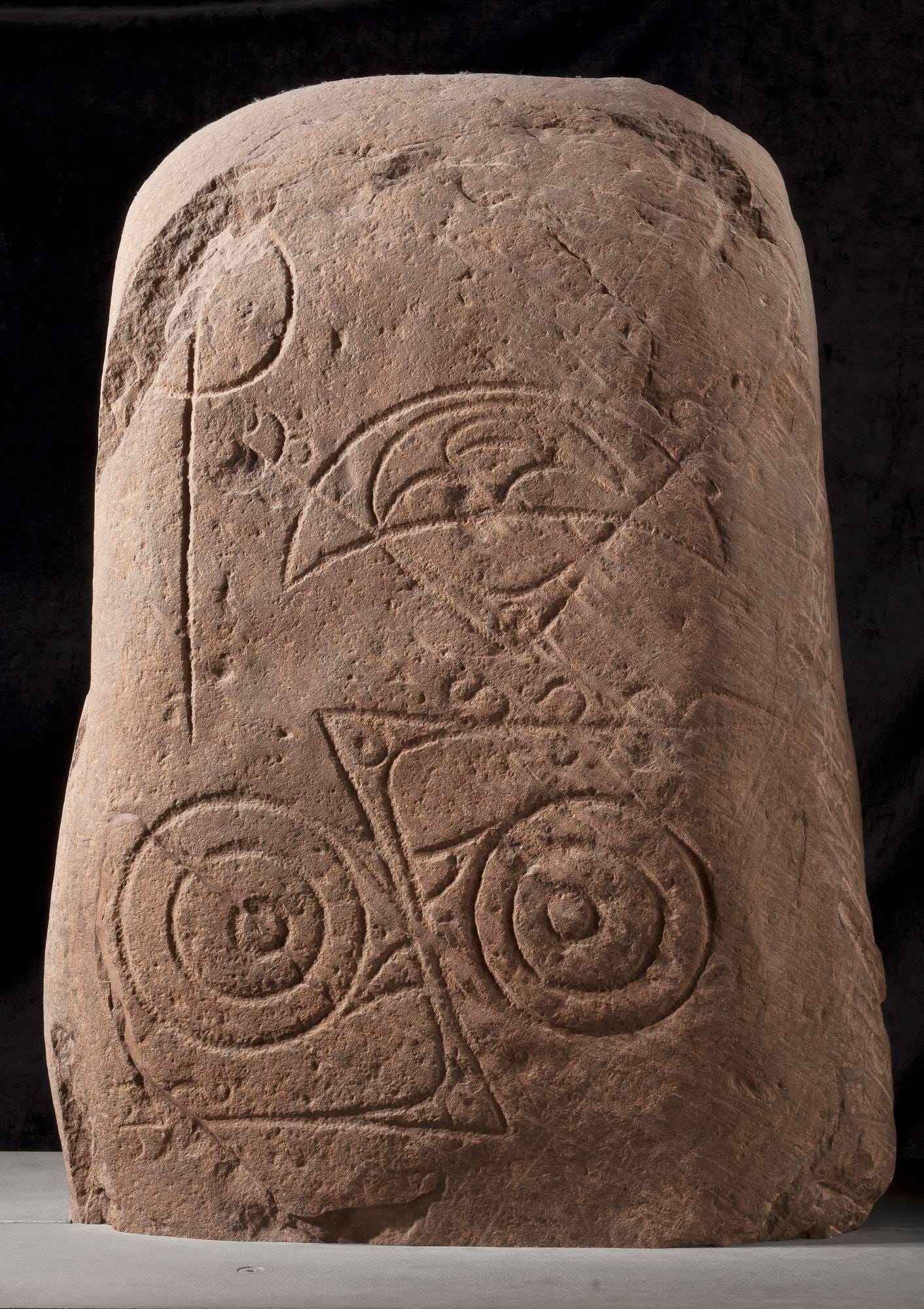

Perhaps just as well, as a quick peek inside also felt disorientating. Here was another Class I Pictish symbol stone, sending me back in time to the seventh or eighth century – long before the establishment of the tenth-century Kingdom of Alba, the forerunner to the Kingdom of Scotland.

I decided to call it a day and come another time, when I’m feeling more prepared.

The challenge of making sense of early medieval Scotland

None of this is any kind of diss on the National Museum of Scotland. Early People and Kingdom of the Scots are carefully curated collections, which aim to show how the nation we call Scotland emerged from a tangle of peoples, practices, beliefs, aspirations and environmental pressures.

In a way, feeling overwhelmed was probably a totally appropriate response: this is a dense and difficult story to tell, and the lack of documentary sources prior to c. 1100 makes it hard to place any of the early medieval artefacts into their historical context with any degree of certainty.

The challenge of making sense of the early medieval period is the thing I find most exciting about it – and the fact that the tenth century is one of the murkiest parts of it makes it more exciting still.

So next time I visit, I plan to actually have a plan – and hopefully come away feeling enlightened rather than confused.

(Any recommendations for what I should see would be much appreciated!)