The Kinloss Stone: Evidence of an early medieval ecclesiastical site in Kinloss?

In which I go on the trail of a Pictish cross-slab fragment discovered in 2017

You may remember that for my MA research topic, I’ve chosen Sueno’s Stone, a massive early medieval carved monument in Forres, Moray, Scotland.

More specifically, I want to examine the theory – first put forward in 1984 by the late Professor Archie Duncan, one of the giants of medieval Scottish history – that the stone commemorates the death of Dubh mac Máel Coluim, who was king of Alba (Scotland north of the Forth) from 962-966 AD.

(Warning: many kings, royal progenitors and pretenders to the throne of Scotland from the 10th-12th century were called Malcolm – or rather its Gaelic version, Máel Coluim. Don’t feel you have to keep up with all the Malcolms unless you really want to.)

Murdered in Forres, body hidden in Kinloss

Professor Duncan’s theory rests mostly on the fact that, according to a 14th-century manuscript that chronicles the reigns of the kings of Alba, Dubh was killed in Forres, possibly in dubious circumstances.

The so-called Chronicle of the Kings of Alba tells us:

“Dub, Malcolm’s son, reigned for four years and six months; and he was killed in Forres, and hidden away under the bridge of Kinloss. But the sun did not appear so long as he was concealed there; and he was found, and buried in the island of Iona.”

Having grown up around Kinloss and Forres, there’s quite a lot I find puzzling about this statement. I’m not going to go into all of it in this post! But one thing that keeps coming back to me is that I am – or at least I was – fairly sure that “Kinloss” didn’t exist as a place in 966 AD.

As far as I was aware, Kinloss only came into being in 1150, when David I founded a Cistercian monastery there as part of his efforts to subdue the troublesome northern province of Moray. There certainly wasn’t any Pictish archaeology in the immediate area that I knew of.

The discovery of the Kinloss Stone

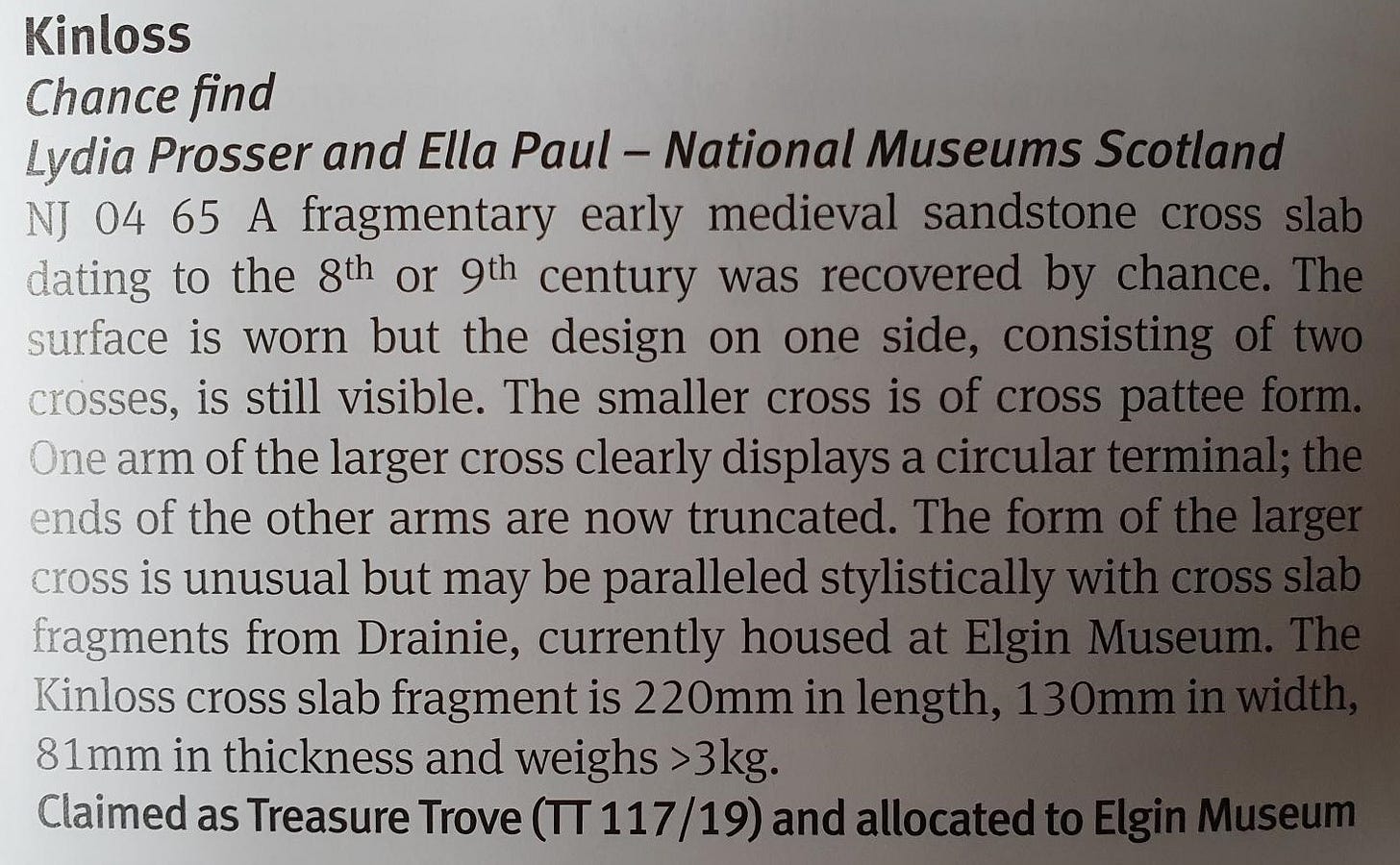

But then I happened to be leafing through Archaeology Scotland’s Discovery and Excavation in Scotland report for 2020, when I came upon this entry:

Whoa, I thought. Perhaps there was an early medieval settlement in Kinloss after all!

Actually I was a bit annoyed at first, because in my mind, part of my MA thesis was going to be that Dubh’s body couldn’t have been hidden under the bridge in Kinloss in 966, because there wasn’t anything at Kinloss in the 10th century – let alone a bridge (which I’ll come to another time).

Then I had a stern word with myself, to the effect that as a historian I should welcome new evidence of any kind, not get irritated at new evidence that seems to blow my pet theory out of the water.

(When you’re a content writer for tech companies, as I currently am, you’re kind of encouraged to leave out stuff that doesn’t fit the client’s narrative. When you’re a historian, not so much.)

And then I remembered something I’d read in the opening chapter of Dr Neil McGuigan’s book Máel Coluim III, Canmore: The World of an Eleventh-Century King.

In it, Dr McGuigan provides a good overview of the ups and downs of the House of Alpin, the royal dynasty that ruled Scotland north of the Forth from 843 to 1034.

Having noticed that two members of this dynasty (Domnall mac Causantín in 900 and Dubh in 966) apparently died in Forres, he felt moved to include a little box-out about the town.

In it, he offers the following supposition:

“In the twelfth century, after a failed bid by Áengus mormaer of Moray to install Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair as king, the victorious David I took direct control of Áengus’s land and founded a Cistercian monastery near Forres, Kinloss Abbey. Situated on the edge of such an important Viking Age centre, it is likely that Kinloss Abbey’s Cistercians took over from an earlier monastic house, perhaps one of Pictish origin.”

Evidence of a Pictish monastery in Kinloss?

I was suddenly excited again. Could this “chance find” in Kinloss of an early medieval carved stone fragment be the first actual evidence of a Pictish monastery that historians only supposed must have existed?

Of course, it would depend on exactly where the fragment was found. If it was near the Abbey, it might be quite persuasive. DES gave the general area of the findspot as NJ 04 65. Typing this into OS Maps produced the following result:

So the stone wasn’t found somewhere around Kinloss Abbey – which is located just underneath the ‘l’ of Kinloss on the above map – but apparently in the sea off the coastal village of Findhorn.

A chance find indeed!

Elgin Museum sheds more light on the Kinloss Stone

That was only the general area, though. I’d seen that the stone had been allocated to Elgin Museum, so yesterday I got in touch with them asking for any information they might have about it.

I wasn’t expecting to hear back for a while – Elgin Museum is staffed by volunteers and is currently closed to the general public – so I was delighted when Janet Trythall, Archaeology Volunteer and board member of the Moray Society, got back to me almost immediately.

First things first, Janet sent me two photos of the ‘Kinloss Stone’: one on its own, and one (below) with the stone displayed above Drainie 32, the cross-slab from the known Pictish monastery site at Kinneddar (Drainie) mentioned in the DES entry. The latter features in its central roundel a Maltese-style cross pattée, similar to that on the Kinloss Stone.

Secondly, Janet confirmed that the findspot of the Kinloss Stone, if not actually in the sea, wasn’t far off where the map reference indicates. It was found in 2017 “on the beach just east of the mouth of the River Findhorn” – so not really in Kinloss at all.

(I wonder if Findhorners are miffed it hasn’t been named the Findhorn Stone.)

The mystery deepens (unfortunately)

As Janet noted in a letter of thanks to the Pictish Arts Society, who helped to fund the conservation of the stone, this raises more questions than it answers. Does the stone actually come from a site in the Findhorn/Kinloss area, or has it just ended up here?

She wrote:

“Given the strength of the longshore drift westwards, has it come from the Pictish fort site at Burghead or the carved stone workshop at the early Christian settlement at Kinneddar, Lossiemouth? Or down the River Findhorn perhaps from Relugas? Or en route by sea from Portmahomack, the boat capsizing in the tricky Findhorn entrance?”

Until and unless any more fragments are found, these questions are sadly likely to go unanswered.

And I’m not sure I’m any further forward in establishing whether there was an early medieval settlement site in Kinloss, with a bridge under which the murdered corpse of Dubh mac Máel Coluim might or might not have been hidden in 966 AD. But as wild goose chases go, it’s definitely been a fun one.

Hi Fiona, what a lovely blog to make me smile, thanks! I am so glad you can laugh about changing your mind, way to go. Just a little comment if I may, the Drainie stone is upside down, the mirror + comb are always below the main components on Pictish stones, not on top. Also, we have done a fair bit of work on Sueno's stone, which you are welcome to, by joining our group Pictish symbols: Art and Context. Don't worry though, there's always plenty more to go.

Hi Fiona. Thanks for highlighting this, I wasn’t aware of this find. On Kinloss and a bridge can I throw in one of my pet theories? There’s never been an accepted etymological root for Kinloss but for me it would make sense if it was head (kin) of the loxa (lossie from Ptolemy). The current outflow of the Lossie is fairly recent, it is a very meandering river and did always feed the Laich. An outflow from the Laich (or a meandering Lossie) into Findhorn Bay would then make sense of Kinloss. Not sure where a bridge would be located mind you. Somewhere near Roseisle providing access to the Burghead island? All speculation but I do think the core samples do support at least the presence of the watercourse. Certainly don’t think they can be talking about a bridge over Kinloss burn!