Bell, broch or bloomery? Deciphering the ‘tower-like object’ on Sueno’s Stone

In which I consider an intriguing theory about a key element of the stone’s battle iconography

(If you’re new to this Substack (hello!) and you’re not familiar with Sueno’s Stone, it might be worth reading Historic Environment Scotland’s short intro to it before reading this post.)

For this blog I want to explore an object depicted on Sueno’s Stone that I haven’t discussed yet, but which has been the subject of much speculation over the years with no solid consensus emerging.

It’s an intriguing object because it sits right in the centre of the array of brutal battle scenes on the reverse face of the stone, suggesting it has an important message to convey.

A central element of a complex battle narrative

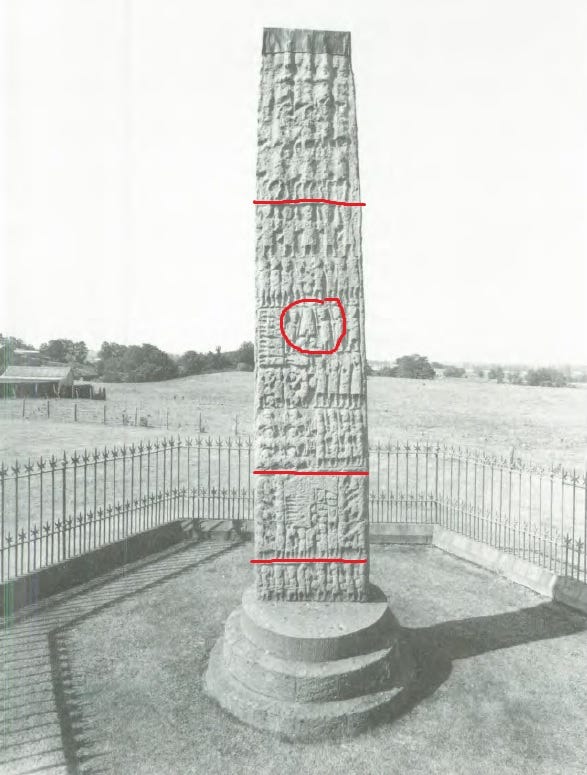

Programmatically, this object sits in the second from the top of the stone’s four narrative panels, which I’ve outlined in red below with the object circled.

From the top, this large and busy panel first depicts a leader and his men front on to the viewer, wielding weapons, then two armies engaged in close combat. On the left, two warriors have turned away from the battle, as if fleeing in defeat.

This action scene is then followed—or perhaps more accurately interrupted—by what appears to be a scene from the aftermath of the battle. Six headless corpses are stacked at one side, their hands tied behind their backs. A seventh lies near them, under the feet of a warrior from the victorious side.

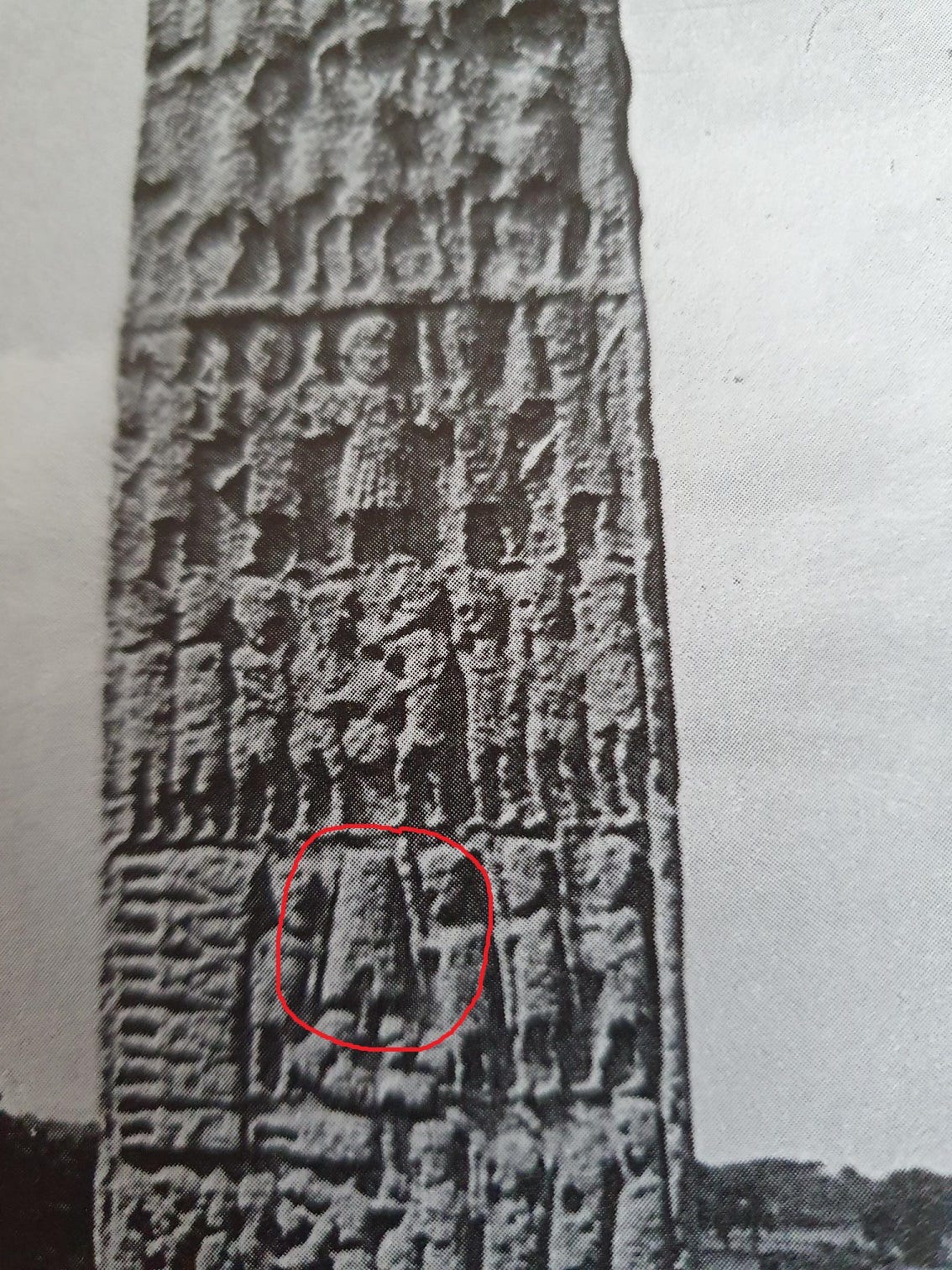

This warrior and three of his companions, all wielding what seem to be spears, are surrounding the object that I want to examine (circled again below).

For the moment let’s just say it looks like a truncated cone, with a notch cut in its front at the base, and something protruding or emerging from the notch. Directly beneath this protruding element lie the six heads that have presumably been removed from the corpses on the left.

The next scene returns to the battle, as shown in John Borland’s drawing below. To the left, warriors of the opposing sides meet in close combat, battling with swords and (on the winning side) shields. Four more severed heads lie underfoot and roundabout. In the centre, the leader of the victors is holding a head that he has seemingly cut off the seventh corpse noted above. To the right, three trumpeters proclaim the victory.

The final scene of this panel depicts the battle rout. Eight warriors from the winning side, two armed with bows and six with swords and shields, pursue six warriors of the defeated army, who are fleeing on horseback.

A huge amount is happening in this panel, and the truncated conical object seems central to it all. It’s clearly very important. But what is it? To date, most of the scholars and antiquarians who have commented on it fall into one of two camps: bell or building.

A bell tolling for the dead?

Firstly, in their superb 1903 survey of the early medieval sculptured stones of Scotland, John Romilly Allen and Joseph Anderson observed:

…in the third row [of the panel], an object shaped like a quadrangular Celtic bell and five [actually six] human heads beneath it; on the left a man holding a staff and on the right a row of three other similar men; behind the man on the left are six decapitated human bodies, and below his feet a seventh headless corpse. [my emphasis]

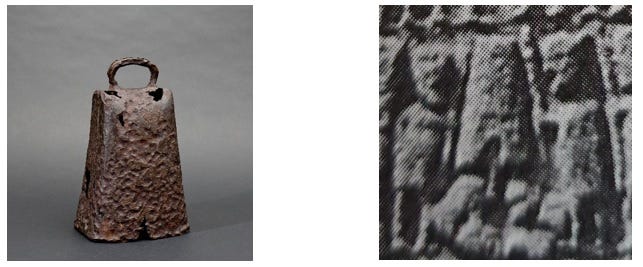

Thus was born one of the theories about this object: that it represents an iron hand-bell of the kind associated with saints and monastic practice in Ireland and Scotland in the years from 600 to 900 AD.

This interpretation was elaborated further by the anthropologist Dr Anthony Jackson in his 1984 book The Symbol Stones of Scotland. Noting that the object sits at the centre of the narrative, he saw it as a “Celtic bell” tolling for the execution of the figure whose head has just been cut off:

This judicial execution is accompanied by the tolling of a bell and a fanfare of trumpets. The central position of the bell in the composition suggests that this was also a triumph for Christianity in putting down the pagan Picts.

Doubt cast on the ‘bell’ theory

However, in a recent lecture for the Pictish Arts Society, Cormac Bourke, the foremost expert on early medieval ecclesiastical hand-bells, made a number of observations that cast significant doubt on the bell theory.

Firstly, Bourke pointed out that Allen and Anderson didn’t say the object represents a bell, only that it’s shaped like one. Secondly, he noted that if the object on the stone is to scale, it’s much bigger than an early medieval hand-bell, of which the largest surviving example is only 30cm tall.

Thirdly, he observed that the object on the stone has a notch cut into its front, which hand-bells do not have. And finally, and the clincher for me, he noted that the object lacks one of the key features of a hand-bell, namely the handle.

A broch under siege?

In any case, the bell theory hasn’t won many supporters over the years. By far the most popular interpretation to date is that the object represents not a bell but a building of some kind: a tower, a fort, or—given its conical shape—a broch.

Brochs are sophisticated drystone-built round towers, dating from the Iron Age and particularly concentrated in the far north and west of Scotland, in Sutherland, Caithness, Orkney, Shetland and the Hebrides. The most intact example surviving today is on Mousa in Shetland, and its conical shape and entranceway do bear a strong similarity—at least at first glance—to the object on Sueno’s Stone:

Leslie Southwick, in an extended description of Sueno’s Stone written for Moray District Libraries in 1981, certainly saw it as a broch-type building—one that’s under siege by the army depicted on the stone:

The next scene centres around a tower, broch or fortress. Extending from the arched entrance is a short stem which may indicate a ladder, stairway or battering ram. To the right of the tower are three figures in shift-like hauberks who face to the left and brandish spears… This scene may represent the besieging of an important stronghold.

Southwick’s interpretation takes its cue from the late Dr Euan MacKie, a notable broch scholar. In his 1975 book Scotland: An Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to the 12th Century A.D., MacKie not only proposed that the object is a broch, but also suggested exactly which one it might be:

It is quite possible that there was a well-preserved broch on or near the battlefield which was shown on the stone. Indeed 46km away to the north-west as the crow flies, on the south shore of the Dornoch Firth there was a broch that still had tower-like proportions 450 years ago; Dun Alascaig was described as having a bell-shaped appearance in 1520. Perhaps the presumed defeat of Sueno took place there.

This argument received short shrift from the late Professor David Sellar, however. In a 1993 paper called Sueno’s Stone and Its Interpreters, Sellar wrote that the Dun Alascaig idea “strains credulity” since that broch is so far from Sueno’s Stone in Moray. However, he declined to make an interpretation of his own for the object, as did the art historians Isabel and George Henderson, and many other commentators on the stone.

Most recently, Professor Gordon Noble and Dr Nicholas Evans of the University of Aberdeen have offered a slightly revised interpretation of the broch theory. In their (excellent) 2022 book Picts: Scourge of Rome, Rulers of the North, they write:

The centre of this panel has a vivid scene of decapitation centred around some sort of tower-like building, possibly the gatehouse of a fort. Headless corpses and severed heads are found around this building.

So rather than a broch—a type of structure that was never built in Moray, where Sueno’s Stone stands—Noble and Evans are picturing a fort, perhaps like the one that Noble and his team are currently excavating at Burghead, only 16km along the coast from Sueno’s Stone.

However, if we accept Cormac Bourke’s argument about scale, the object on the stone is clearly too small to be a broch, fort or gatehouse. Could it be something else entirely?

A battlefield furnace?

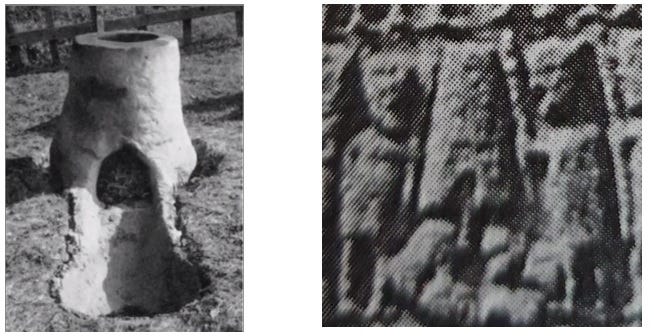

One theory that’s flown slightly under the radar, but which Bourke was keen to highlight in his lecture, is that the object represents an iron-smelting furnace or bloomery.

Bourke credits the aerial archaeologist Ian Keillar as the originator of the ‘furnace’ theory, although it seems Keillar himself never wrote it up. Rather, he suggested it in personal correspondence to fellow archaeologist Ian G. Shepherd, who included a nod to it in a 1993 paper called The Picts in Moray:

Given that the head-hunting theme evident on Sueno's Stone has deep Celtic Iron Age roots (although Ian Keillar (pers. comm.) sees the 'broch' as Nebuchadnezzar's furnace […]) it is all the more remarkable that Sueno's Stone also links us with the time of conversion through the mighty twenty feet tall cross on the other face. [my emphasis]

In the Book of Daniel, king Nebuchadnezzar II orders Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego to be cast into a fiery furnace for refusing to worship his statue. But there’s no suggestion on Sueno’s Stone that people are being thrown into the furnace-like object. Rather, the bodies and heads of the defeated army remain outside it: bodies at the side, heads directly beneath. So what is a furnace doing in the centre of a gruesome battle narrative?

Two theories about the Sueno’s Stone ‘bloomery’

This is where things get quite intriguing, and two new theories emerge.

Firstly, during a conversation on Twitter about Cormac Bourke’s lecture, it occurred to me that the four figures at either side of the ‘furnace’ are approaching it holding spears. Could they be planning to melt down the captured weapons of the vanquished enemy?

By showing the enemy forces decapitated and their weapons melted down, Sueno’s Stone would be communicating a message of total victory—a message very in keeping with the stone’s massive seven-metre height. But is weapon-melting something that would actually happen in the aftermath of an early medieval battle?

In search of an answer I turned to the literature on one of the most-analysed pre-1066 battles on British soil, and one that may even be contemporary or near-contemporary with Sueno’s Stone: the battle of Brunanburh in 937 AD.

Here, the Saxon king Æthelstan defeated a coalition army led by Olaf Guthfrithson, the Norse king of Dublin; Owain, king of the Britons of Strathclyde; and Causantín mac Aeda, the Gaelic king of Alba (a sort of proto-Scotland). Known in its day simply as “the great battle,” it’s often cited as a pivotal event in the formation of England.

Were enemy weapons melted after Brunanburh?

In his 2021 book about the battle, Never Greater Slaughter: Brunanburh and the Birth of England, the military historian Dr Michael Livingston writes that melting of the enemy’s weapons was indeed something that happened in the aftermath of Brunanburh. On page 34, he tells us:

Nothing came clean from the battle, but the sooner it was recycled the sooner the carnage could be left behind… Corpses were searched and stripped, their belongings gathered and brought to sorting sites where what was intact and useful was separated from what could be melted down and recycled for its valuable metals… Useable spearheads were pulled off snapped shafts, and those that couldn’t be reused were thrown into a pile for melting down in the fires that were stoked as hot as the men could manage. [my emphasis]

This seemed highly promising, until Dr Neil McGuigan of the University of St Andrews sounded a note of caution in the Twitter chat:

A small amount of Googling suggests that he’s correct: the high temperatures needed for melting (as opposed to softening) iron apparently weren’t achieved in Europe until the fifteenth century. And besides, a bloomery furnace of the type shown above wasn’t designed for melting metal objects, but for extracting iron from iron oxide.

But Livingston seems confident that spearheads were melted down in the aftermath of Brunanburh. Where did he get this information from? It turns out his source is a single account of the battle of Crécy in 1346, written by an anonymous citizen of Valenciennes and included on pp 210-211 of Livingston’s 2015 book The Battle of Crécy: A Casebook.

From it, he quotes this extract, translated by his colleague Dr Kelly DeVries with minor edits by me:

Et au chief de deux jours que les Englecqs eurent prins des armures des mors, tant qu’il leur pleut et que bon leur sambla, le roy fist tout le remanant des armures, vièses et nouvelles, bonnes et mau-vaises, mettre en une grande place emmy le champ, et fist bouter le feu dedens et tout ardoir, par quoy nul n’en eusist jamais nul aise.

And after two days the English had taken as much armour from the dead as they wanted and seemed good to them, the king put all the remaining armour, used and new, good and bad, in a large place amid the field, and burned it all so that no one could ever use it again.

However, not only was Crécy fought 400 years after Brunanburh, but this account also refers to armour (armures), not weapons (armes). And the text immediately preceding it strongly implies that the armures burned by the English weren’t metal, but the fabric surcoats, mantles and coats of arms that medieval knights wore over their steel armour to identify themselves:

Adont print le roy monseigneur Godeffroy de Harcourt et plenté d’aultres compaignons, et alèrent serchier les mors; et fist prendre tous les tournicles, mantelynes ou cottes d’armes, ainsy que pluseurs les nomment, des grans princes et des grans chevaliers, et les fist apporter en sa tente… Et y eult de tournicles en la tente du roy, où on les apporta, ce tesmoignèrent ceulx qui les virent et regardèrent, bien .xxii.c. et plus.

Then the king took Sir Godfrey of Harcourt and many other companions, and they went to search the dead. They ordered to be removed all their surcoats, mantles, or coats of arms; thus many of the great princes and great knights were identified, and they had them carried into their tents… And according to those who saw and looked at them, as many as 2,200 or more surcoats were brought to the tent of the king. [my emphasis]

(The translation above is mostly by Kelly DeVries, with the final sentence translated by me for greater clarity.)

On the face of it, then, there’s no solid basis for arguing that weapons were melted down after Brunanburh or any other early medieval insular battle. In fact my rather uncharitable view is that Livingston is stretching the evidence in a bid to make it fit with some corroded metalwork finds unearthed at Bromborough on the Wirral, his preferred site for the famously-unlocated battle.

A symbolic melting of weapons?

But I do have one other thought. Could the furnace on Sueno’s Stone—if that is what it is—represent a symbolic melting of weapons, rather than a real activity that happened on a real battlefield?

Interestingly, there is some slight evidence to support this idea. While digging around in Livingston’s sources, helpfully gathered into a single volume called The Battle of Brunanburh: A Casebook, I came across the text of an Old English battle prayer, preserved on folios 5r to 6r of an eleventh-century prayer book archived in the British Library as BL MS Cotton Galba A.xiv.

Part of it reads as follows:

For bryt drihten heora wapna & heora sweord to bret & do drihten þæt hy for meltan on minre gesihþe . swa swa weax mylt fram fyres ansyne…

This was translated by Walter de Gray Birch as:

May God crush their arms and smash their swords and melt them in my sight just as wax melts before a fire…

As I was already in correspondence with Cormac Bourke on another topic (the possibility of a lost early medieval hand-bell at Auldearn), I mentioned this symbolic-weapon-melting idea and this battle prayer to him to see what he thought.

He kindly replied to say that although the melting-down of iron and steel was a technological impossibility in the early Middle Ages, it does recall an episode recounted by Adomnán of Iona in his Life of Columba, in which the monks of Iona melt down a knife that St Columba had blessed, to transfer its holy power to other implements:

When this came to the knowledge of the monks, they skillfully melted down the iron of the knife and applied a thin coating of it to all the iron tools used in the monastery. And such was the abiding virtue of the saint's blessing, that these tools could never afterwards inflict a wound on flesh.

So here we have two examples, from the eleventh and seventh centuries respectively, of the idea of weapons being melted in order to neutralise their potential to maim, kill, or present a military threat. So perhaps this isn’t a *total* dead end in relation to a possible furnace on Sueno’s Stone.

[UPDATE 17th June: Thanks to Helen McKay for pointing out that the knife blessed by Columba wasn’t melted to neutralise its potential to do harm, but to transfer its power to prevent harm - an important distinction.]

A ritual humiliation?

Meanwhile, though, Cormac Bourke had come to a different and equally intriguing idea about the role of the furnace object. Noting that the severed heads of six enemy warriors were arranged directly below it, he wondered if it represents a ritual humiliation by which the slag from the furnace is being made to run out on to the heads of the defeated.

Bourke solicited the opinion of Dr Tim Young of Geoarch, who specialises in archaeometallurgy. Young replied with some interesting thoughts, noting that depictions of iron-smelting furnaces are “extremely rare in antiquity” but agreeing that the shape of the object is “very furnace-like.”

To the idea of the furnace slag being used for ritual humiliation, Young observed that this wouldn’t be “particularly spectacular” in itself, but that since smelting is sometimes given a sexual metaphor, it “could be viewed as degrading from that viewpoint.”

Lastly he noted a possible later medieval parallel, in which the head of an execution victim might be preserved in tar before being displayed on a spike; as seems to have been the gruesome fate of William Wallace in 1305.

Was melting of weapons possible after all?

This was all very interesting in itself, but when I followed up with Dr Young to ask for his permission to include his comments in this blog, he responded with some further thoughts which are even more intriguing. Notably, the fact that re-melting of iron was a technical possibility in antiquity (and thus presumably also in the early medieval period) after all, and may even have been a “regular occurrence.”

Young cited two processes that entailed the remelting of iron: the Evenstad process in which a freshly-smelted bloom of iron would be re-melted in a shallow hearth to reduce its phosphorus content, and the Aristotle process, which involves the remelting of iron in a very small furnace to control its carbon content.

While the Sueno’s Stone object resembles neither a shallow hearth or a very small furnace, Young added that a normal iron smelting furnace could also be used for simple remelting. It would be easier to reforge a spearhead into something new rather than remelt it, he said, but “recycling via remelting is also certainly a realistic process.”

So it’s looking more and more like the furnace theory may be worth further investigation. It would be good to hear anyone else’s thoughts on this topic.

Conclusion: A promising interpretation

In conclusion, then, Cormac Bourke has provided a very interesting and at first look quite promising new(ish) interpretation for the central object on Sueno’s Stone that has previously mostly been identified as a bell or a broch-type building.

The scale of the object in relation to the figures and other elements on this face of the stone strongly suggests an item of slightly less than human height, and the shape, frontal notch and protruding element bear a strong similarity to an early medieval iron-smelting bloomery furnace with a channel for ironworking slag or the slag itself emerging at its base.

The fact that the object is being approached or surrounded by warriors bearing spears perhaps suggests an actual or symbolic melting-down of captured enemy weapons, while the fact that the severed heads of the defeated army are arranged immediately below the object perhaps suggests some kind of ritual humiliation involving slag from the furnace being run out on to these heads.

I would be really interested to hear anyone else’s thoughts on these interpretations of this central object. In the meantime, I’m very grateful to Professor Jane Geddes of the University of Aberdeen for inviting Cormac Bourke to talk to the Pictish Arts Society and for putting me in touch with him afterwards, and to him and Tim Young for their time and their fascinating further thoughts on this topic.

References

Adomnán of Iona, Life of St Columba

Allen, J. Romilly, and Anderson, J. Early Christian Monuments of Scotland (1903)

British Library MS Cotton Galba A.xiv ff.5r-6r

Cleere, Henry. Ironmaking in a Roman furnace (1971)

Henderson, Isabel, and Henderson, George. The Art of the Picts (2004)

Jackson, Anthony. The Symbol Stones of Scotland (1984)

Livingston, Michael. Never Greater Slaughter: Brunanburh and the Birth of England (2021)

Livingston, Michael. The Battle of Brunanburh: A Casebook (2021)

Livingston, Michael, and DeVries, Kelly. The Battle of Crécy: A Casebook (2015)

Loggie, Ruth. A Revisit to Sueno’s Stone (unpublished MSc dissertation, University of Aberdeen, 2020)

MacKie, Euan. Scotland: An Archaeological Tour from Earliest Times to the 12th Century A.D. (1975)

Noble, Gordon and Evans, Nicholas. Picts: Scourge of Rome, Rulers of the North (2022)

Sellar, David. Sueno’s Stone and its Interpreters (1993)

Shepherd, Ian G. The Picts in Moray (1993)

Smith, Lesley M. (ed.) The Making of Britain: Volume 1: The Dark Ages (1984)

Southwick, Leslie. The So-Called Sueno’s Stone at Forres (1981)

I love the way you take an idea and work away at it to see where its leads, well done Fiona. About the ‘furnace’ idea. To me, all your research ends up pointing to an unacceptable scenario on a number of levels, meaning the original idea is untenable upon close inspection. To begin with, the small thing extending from the bottom of the item isn’t big enough, or connected to the opening, so doesn’t look like a furnace outlet. And I agree with your assessment that at this period, furnaces weren’t large enough or hot enough to melt down a pile of enemy weapons.

Then, warriors with spears are found on many CII stones, and of course in texts, so to reinterpret the normal motif of a warrior with a spear as a man bringing a weapon to be melted down would just be confusing to the viewer.

But more importantly, the idea of melting weapons down and pouring them over severed heads is not what happens to heads of dead warriors in a Celtic context. We have lots of information, textual and archaeological, about how the Celts conceived of their weapons and how they treated them after the death of their warrior. Weapons were handed on to the next hero, they were bent or broken and returned to the water, stored in sacred sites as untouchable items, they were honoured as having their own spirit and agency. Again, this is a ritual space on the stone, so we must expect ritual scenes to be understandable by the viewer within their cultural context.

The story about the knife of Columba being ‘skillfully’ melted down after his death and spread over items to provide a blessing is a great find. This was likely just his knife used for everyday tasks like carving food, it’s a relatively small item, the swiss-army knife of its day, and as above, could be melted down in the local hearth, but not for the purpose of destruction or humiliation but to *preserve* its essence – a typical Celtic idea. This story demonstrates that melting down something was *not* considered to destroy its potency. And the ‘skillfull’ meltdown implies this was a very unusual activity, requiring unusual skills.

In the end, there seems nothing to support a ‘furnace’ idea then. Back to ‘broch’ methinks, if it looks like a broch, acts like a broch, smells like a broch …

Excellent as ever.

Only comment on your core thesis is to bear in mind that scale on carvings of this period wasn’t something the artists really cared about. I think John Borland made this point at the end of Cormac’s PAS lecture. So whatever the shape is it could be something as small as a bell or as big as a broch - or something in between like a furnace!

My other observation is not related to this but to the fleeing horsemen in the next panel. I hadn’t noticed before but the six horsemen have only one leg between them! Now the figurative carving on Sueno’s Stone isn’t the best and is quite different in many ways to other representations of figures on other Pictish stones. But, that said, carved Pictish horsemen are generally depicted with their legs (usually both) visible below the horses belly. These don’t. Also the heads are sitting almost directly on the horses’ backs with at best a neck and certainly no body. Is this actually some mythic part of the story where the victims heads fled or were sent back whence they came? If they are fleeing living horsemen then they are very poorly executed, even by Sueno’s Stone standards. Admittedly the horsemen in the top panel don’t seem to have legs either (as far as I can make out - damn the weathering!) but they certainly have bodies

Left field idea, I know, but maybe worth considering?

I’m put in mind of the tale of Sigurd and Maelbrigte (he of the tooth) only in the image of a decapitated head being taken away on horseback rather than Skene’s theory that that is the story the stone is telling in its entirety.

As usual, feel free to ignore my musings