Bell, motte and sundial: in search of early medieval Auldearn

Im which I weigh the evidence for a Nairnshire village as an early medieval settlement site

How do you deduce the existence of an early medieval site?

In England, where the documentary record is pretty good, clues might come from places named in Domesday Book, in early charters, or a source like the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Historians knew of Cynethryth’s lost monastery at Cookham long before it was found in 2021, because it appears multiple times in eighth-century charters.

But for the area around the Moray Firth, it’s not so easy. Barely any written records survive from Scotland from before the twelfth century, and those that do mostly mention places in central Scotland: Dunkeld, Forteviot, Scone, St Andrews, and so on.

A few northerly places do get a look-in. Adomnán tells us St Columba visited Inverness in the sixth century, and Bishop Curetán of Rosemarkie witnessed a law code in the seventh. Then there’s a gap until the tenth century, when the Scottish king-lists tell us two kings died in Forres, plus one at ‘Ulnem’ or ‘Ulurn’ (likely Blervie, near Forres), and one at Cullen. In 966, the body of king Dubh was hidden under a bridge at Kinloss. Lastly, in 1040, Macbeth killed Duncan I at Pitgaveny near Elgin.

But that’s pretty much it. Places that we now know were important in the eighth, ninth and tenth centuries, like Burghead, Portmahomack and Kinneddar, are totally absent from the historical record. And while the huge fortifications at Burghead have always been obvious, we only know about Portmahomack and Kinneddar because fragments of carved stone turned up there in sufficient quantities to justify excavation.

But what about sites that aren’t mentioned in the records, don’t have obvious fortifications and don’t have any early medieval stone sculpture? Are we missing places around the Moray Firth coast that we should be looking at? I think definitely yes, and I’d like to propose that one of these missing sites is Auldearn in Nairnshire.

Battles, witch-trials and betrayals: Auldearn’s dramatic history

For an unassuming village, Auldearn has a remarkably dramatic history. It’s well known as the site of a battle in 1645, where Montrose’s army of Royalists defeated an army of Covenanters; Scots opposed to Charles I’s imposition of a bishop-led church.

A few years later, Auldearn was the focus of one of Scotland’s most notorious witch trials. In 1662, a local woman, Isobel Gowdie, made a series of extraordinary confessions to witchcraft; as a result of which she and another woman, Janet Breadhead, were put on trial and almost certainly executed locally.

Just across the road from the 1645 Inn is a National Trust for Scotland-owned property called the Boath Doocot, an eighteenth-century circular dovecote that stands high on an artificial mound at the western entrance to the village.

This mound is known – or rather, generally assumed – to be a twelfth-century motte; one of a neatly-spaced chain of garrison castles built by David I (r. 1124-1153) and William I (r. 1165-1214) to exercise their authority over the north of their kingdom.

Twelfth-century Auldearn was not yet considered ‘old’, so in those days its name was simply Earn, usually spelled ‘Eren’ in contemporary charters. And it’s at William I’s castle of Eren that the curtain goes up on Auldearn’s documented history, which begins in medias res in 1186 with the king’s marshal, Gillecolm, ‘betraying’ the castle to the king’s local enemies, the powerful MacWilliams.

Auldearn before the Anglo-Norman era: A rich pre-history

Since Auldearn doesn’t appear in any contemporary sources before 1186, that’s where historians tend to stop (or start) looking at it – giving the impression that it dates back only as far as the twelfth century. But that seems highly unlikely, for several reasons.

Firstly, like Forres and Elgin, Auldearn lies on a stretch of fertile coastal plain that even in the early middle ages would have been ideal for agricultural exploitation. As Moray has been settled since the Neolithic period, it’s inconceivable that this was virgin territory when David I arrived on the scene.

In any case, the archaeology of the village proves otherwise. Auldearn is an ancient place, with a Neolithic stone row and cairn, and numerous Bronze Age and Iron Age finds – including an extraordinary bronze torc and massive bronze and enamel brooch, found together in 2014 and now in the National Museum of Scotland. According to the 2014 Treasure Trove report, these items display advanced metalworking capabilities and the ability to riff on known styles from Roman Britain.

Early medieval Auldearn: davochs and thanes

Then there are hints in later texts of Auldearn’s importance in the early medieval period. For his 2003 PhD thesis, Alasdair Ross tried to piece together the structure of land organisation in pre-twelfth century Moray, acting on a hunch that the county’s medieval parishes were based on multiples of an older land unit called in Gaelic dabhach (Scots: davoch, pronounced something like ‘doch’ ‘dach’ - thanks to Alastair Fraser for the correction!).

In deciphering the pattern of dabhaichean in Moray from later charters, Ross discovered that the original parish of Auldearn was surprisingly large, comprising 13 dabhaichean from Meikle Urchany in the south-west to Golford in the east.

That large territory also included a thanage, called Moythas (now Moyness), first attested in charters in 1238. As the thane – or toisech as he was known in Gaelic – was an already-established aristocratic rank when the documentary lights go on in the twelfth century, it’s reasonable to assume that Moyness was home to a thane, or king’s agent, in the eleventh century and perhaps even the tenth.

As side-note, Ross notes in his list of dabhaichean in Auldearn that the land of Penick to the east of the village had an “older name” of Kinteisack. As the neighbouring thanage of Dyke also includes a hamlet called Kintessack, I wonder if these names preserve the thane’s Gaelic title of toisech, and perhaps indicate the furthest limit of the thanage. If any toponymists are reading, I’d be keen to hear any thoughts on this.

A cult centre of St Columba?

But perhaps the strongest indication that Auldearn was an important place in the early medieval period comes from another side-note in Ross’s PhD thesis – and one he chose to leave out when he turned the thesis into his 2015 book Land Assessment and Lordship in Medieval Northern Scotland. He wrote:

“There is little doubt that the parochial saint of Auldearn was Colum Cille [i.e. Columba]. Every year on 21 June, a fair was held during his festival. In 1602 it was stated that of the nine acres next to the church, one was called St Columbisaiker. There may have been a significant cult centre for this saint in Auldearn: another of the nine acres was called the Bellaiker.” [my emphasis]

Now, there’s nothing intrinsically remarkable about a parish being dedicated to St Columba. The first abbot of Iona was an instrumental figure in the Christianisation of Pictland, and has had churches founded in his name for 1,500 years.

However, Auldearn bears several hallmarks of an early dedication. A fair held on the saint’s day1 is one indicator, and a place-name (St Columbisaiker) is another. But the real clincher is the mention of a bell, and to an acre of land belonging to it. Ross himself observed that this was interesting, adding:

“Obviously, while there is no method of ascertaining what type of bell this was, the concept of lands supporting an inanimate object is echoed elsewhere in Scotland, where it is known that the custodians of relics received lands in return for the ringing of a bell.”

Ross was looking for evidence of land administration, not saints and relics, so that’s where he leaves it. But if he’d followed this thread only a tiny bit further, he might have ascertained exactly what type of bell it was, and in the process put the history of Auldearn back by at least another 200 years.

The uses of saintly handbells

In essence, an association with a Columban cult and a dedicated plot of land strongly suggests one specific type of bell: the early medieval handbell.

According to Cormac Bourke of the National Museum of Ireland, this type of bell was produced in Ireland and Scotland only in the period 700-900 AD, and in Scotland it is particularly associated with the activities of the early Columban church.

Handbells were made of iron or bronze, and were believed to possess the supernatural powers of the saint with which they were associated. In an excellent lecture on the handbells of Ireland, Bourke explains how these sacred relics were used for many purposes, including (but not limited to) promulgating laws, casting out devils, and sanctioning wrongdoers by ringing a bell against them or by burying a bell in a souterrain.

More prosaically, Bourke says the handbell was also an important piece of early monastic equipment, used in conjunction with a sundial to call clerics to prayer at the appropriate hour. It was state of the art technology, he says, requiring advanced metalworking skills. The impression I get is that the production and care of a handbell may have been a comparable investment to the creation of a Class II cross-slab – so perhaps a church site without a cross-slab can still be a high-status site.

Further evidence for a sacred handbell?

Is there any more evidence to support the idea that Auldearn had an early medieval church with a precious, sacred handbell? The bell – if indeed it existed – is missing, but there are a few other things to consider.

One is the fact that Auldearn kirkyard does have a sundial, of undefined age. I’m not suggesting the extant sundial is the original monastic partner to the bell, but I do wonder if it perpetuates a tradition: perhaps the current one is here because there has always been a sundial here. (Pretty speculative, I know.)

Even more speculatively, a cropmark feature nearby has been interpreted as a souterrain. Could the bell have been buried here, to “bring wrongdoers to account,” as Bourke puts it?

In fact, this souterrain was the subject of an archaeological evaluation in 2002, which revealed it to be a ‘curvilinear pit’ rather than an underground passage. There’s no mention in Canmore of whether a bell was found in it, or if it was even excavated. So that’s a non-starter, at least for now.

A suggestive juxtaposition of church and motte

But there’s also the evidence of the church itself. It sits on a high mound above the village, a feature characteristic of early Christian church sites, according to Professor Katherine Forsyth of Glasgow University. In her 1995 PhD thesis on the ogham inscriptions of Scotland, she wrote that Dyke church, just a few miles from Auldearn:

“…sits on a large mound within an oval enclosure, two features usually taken as diagnostic of early medieval antecedence.”

And writing in 2010 about the place-name of Auldearn (an intriguing subject for another time), Forsyth’s colleague Professor Thomas Owen Clancy observed:

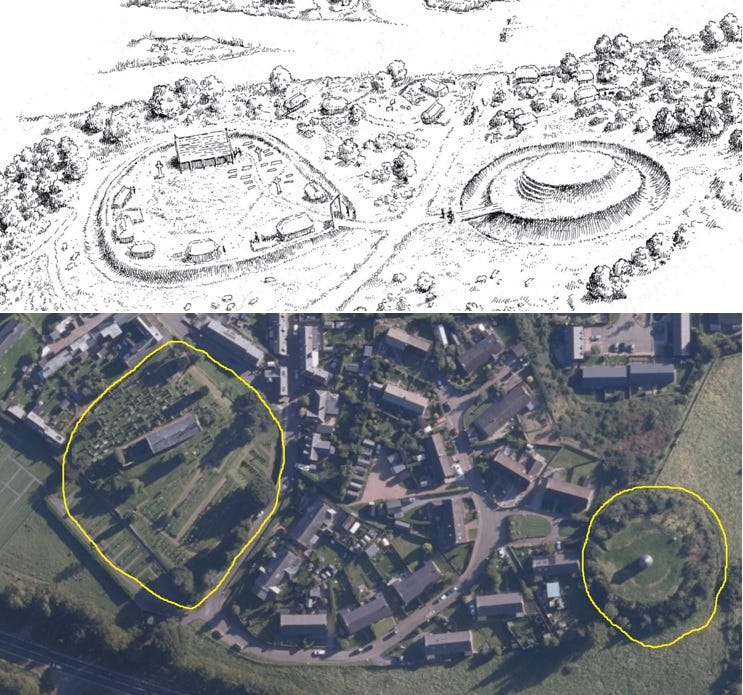

“…in the twelfth century this was a very significant site, and it boasts an impressive motte; the juxtaposition of motte and church (dedicated to Columba) is evocative of an early complex of secular and ecclesiastical power.”

Given the Columban dedication and the inferred existence of a handbell, could the “juxtaposition of motte and church” be older than the twelfth century?

To me, the topography of Auldearn church and motte recall an early medieval landscape that Forsyth and Clancy will know well: the twin sites of Govan Old Church and the (now-lost) Doomster Hill, on the south bank of the River Clyde in Glasgow.

If Auldearn is a similar site to Govan, perhaps the motte wasn’t erected by David I or William I’s castle-builders in the 12th century, but had in fact already been in situ for centuries, serving as a local moot hill or assembly place.

And what about the metalworking skills needed to fashion a quadrangular iron hand-bell? Cormac Bourke has sharp words for one archaeologist who described these early bells as “of rude manufacture”, pointing out that the ability to produce a flat sheet of iron, cut and fold it to shape, rivet its sides together, and insert a circular handle with clapper required a huge amount of expertise.

Is it coincidence that Auldearn is the site of many fine metalwork finds, including the torc and brooch referred to above, as well as a Pictish penannular brooch and more? These finds might suggest a centre of metalworking expertise that may have operated for centuries. If that’s the case, though, nobody has yet found any clear evidence of it.

And finally, if Auldearn did have an early medieval handbell, it wasn’t the only place along the southern shore of the Moray Firth that did. Three other iron handbells of the period are still extant: one found at Barevan near Cawdor and now held at Cawdor Castle, and one at Birnie Kirk, near Elgin.

Most recently, during the ongoing Northern Picts Project excavation at Burghead, an intact handbell – complete with clapper – was unearthed in 2021 from the ramparts of the Pictish fort, as were fragments of sheet iron from a metalworking area.

What about the bellaiker, though?

What we don’t have in Auldearn, or at least not that I know of, is any indication of where the ‘bellaiker’ was, or what it consisted of.

Ross was correct when he noted that plots of land were sometimes associated with relics like handbells. In a 1211 charter of William I, for instance, the monks of Arbroath Abbey were granted a tract of land in Forglen, which came with a famous and now-lost relic known as the breacbennach.

In a 2009 article for the Innes Review, Gilbert Márkus of Glasgow University observed that this tract of land, and its relic, carried obligations for the monks:

“In return the monks were to do ‘the military service which is owed to me from that land, with the foresaid Breacbennach’.”

It’s possible that the Auldearn ‘bellaiker’ was a plot of land allocated to a deòradh, or dewar; a layperson with a responsibility, often hereditary, to look after the bell. In return, the dewar would be free to live on the property. If anyone knows of any place-names in or around Auldearn that reference a dewar or bell, it would be very satisfying!

In conclusion…

To sum up, then, I think the topography of Auldearn’s church and motte, combined with quite compelling evidence for the existence of an early Columban cult with a sacred handbell, suggest it should be considered for inclusion in the ranks of early medieval sites of Moray and Nairn, alongside Kinneddar, Burghead, Forres, Dyke and Wester Delnies.

If anyone has any further thoughts, insights or objections, please do leave a comment.

References

Bourke, Cormac. The Bells of the Irish Saints (2021)

Bourke, Cormac. The hand-bells of the early Scottish church (1984)

Clancy, Thomas O. Atholl, Banff, Earn and Elgin: ‘New Irelands’ in the East Revisited (2010)

Duncan, A.A.M. Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom (1975)

Forsyth, Katherine: The ogham inscriptions of Scotland: An edited corpus (1995)

Márkus, Gilbert. Dewars and relics in Scotland: some clarifications and questions (2009)

Noble, Gordon. Discovering the Northern Picts (2022)

Oram, Richard. David I: The King who Made Scotland (2008)

Oram, Richard. Domination and Lordship: Scotland 1070-1230 (2011)

Ross, Alasdair. The Province of Moray, c. 1000-1230 (2003)

Thanks to Helen McKay who has pointed out that Columba’s day is 9th June, not the 21st, and that the 21st is the summer solstice, thus the fair perhaps perpetuated a pagan festival. Alasdair Ross gives his source for a fair dedicated to Columba on 21st June as Lachlan Shaw’s History of the Province of Moray, but I haven’t been able to find it in my copy. If anyone has any thoughts, please do comment.

Happy new year! No problem at all.

At least one of them near Stirling is 9th/10th century.

Will’s on Twitter and very nice if you struggle to find the reference it may have been it’s phd!

Hi Fiona, another excellent article, bravo. A few comments: in Scotland souterrains tend to be Iron Age or Roman Iron age rather than EM. The terms have slightly different uses between Scotland and Ireland. In terms of mottes, its worth checking the first use of it for your site. Round Stirling the 1960s RCAHMS' volume uses it rather too broadly. Some 'mottes' are lightly defended natural hillocks, they might be med, EM or Iron Age (Will Wyeth has done a section on this somewhere). I suspect in some locations the term is as useful as dun, basically a catch all for things that don't quite fit.

best wishes

murray