Bonus Hogmanay post: Where was King Bridei's fort?

In which I analyse Adomnán's Life of St Columba for overlooked clues to the location of the stronghold of Bridei mac Mailcon, King of Picts.

Happy Hogmanay, and thank you for reading my blog this year! This is a bonus post which you may have seen before, as it was first published a week or so ago on the North of Scotland Archaeological Society (NOSAS) blog. But if you hadn’t seen it, here it is below - and as ever, if you have any thoughts I would be very pleased to hear them.

In my talk to NOSAS in October, I spent some time discussing the episodes in Adomnán’s Life of St Columba (hereafter the Life) in which the holy man visits the Inverness area, which Adomnán locates in provincia Pictorum, in the province of the Picts.

For this blog I want to take a closer look at those episodes. In particular, I want to see if they contain any under-considered clues to the location of the fort where Columba visits Bridei mac Mailcon, king of Picts (r. 554–584), and spars with Bridei’s mage, Broichan.

The link to Craig Phadrig

I’m by no means the first person who has attempted to identify Bridei’s fortress. As long ago as 1793, Robert Rose, George Watson and Alexander Fraser, ministers in Inverness, wrote in the Old Statistical Account of Scotland that:

…on the summit of a rock, called Craig-Phatrick, are the remains of a vitrified fort, generally believed to be Pictish, and if Pictish, probably the remains of the Royal Seat at Inverness, of which Adamnan, Abbot of Jona [Iona], makes mention in his Life of the celebrated Saint Columba; hither, as Adamnan relates, the Saint repaired from Jona, and converted Brudius, the Pictish monarch, to the Christian faith.

Craig Phadrig has been the front runner ever since, strengthened by Alan Small’s excavation of 1971–72, which yielded early medieval pottery and metalworking evidence, as well as one AD 200–800 radiocarbon date. Emergency excavation by Mary Peteranna and Steven Birch in 2015 produced a second early medieval radiocarbon date of AD 416–556 (95% probability).

But Craig Phadrig isn’t the only hillfort in the area, and other sites may have a stronger claim to being the fortress described by Adomnán.

How accurate was Adomnán’s geography?

When I started looking into this, I was struck by how little Adomnán’s otherwise much-dissected text, written around 700, had been analysed for clues to the location of Bridei’s fort.

There has been a tendency to assume that since Adomnán was (ostensibly) narrating events of more than a century earlier, and since his concern was to demonstrate Columba’s holy powers rather than write a factual biography, his descriptions may not be rooted in real topography.

In 1983, for example, the archaeologists Elizabeth and Leslie Alcock came to Inverness-shire in search of the royal site mentioned by Adomnán. However, rather than investigating Craig Phadrig or another nearby hillfort, they chose to dig at Urquhart Castle on Loch Ness.

Part of their rationale was that Adomnán is vague about the location of Bridei’s fort. They wrote:

It is no matter for surprise that Adomnán displays no exact knowledge of either Loch Ness or the River Ness; nor indeed of the geographical details of a mission which had taken place a century before he wrote the Life. In particular, it is unclear whether Adomnán thought that Bridei's fort was beside the river or beside the loch.

In a 1975 article for the Inverness Field Club, the historian and art-historian Isabel Henderson also examined the episodes of the Life set around Inverness. Like the Alcocks, she too felt that the text cannot tell us exactly where the fort was. However, she did note that:

There seems no reason to doubt that [Bridei] lived near the River Ness. For Adomnán’s purposes, there was no real need to say where the royal residence was at all, and he is unlikely to have taken the trouble to invent a location.

I want to propose that Adomnán does in fact give us enough clues to narrow down the location of the fort, and that combining those clues with archaeological and landscape evidence allows three possible sites to be identified and ranked in order of probability.

Adomnán’s descriptions of the Inverness area

To do this we have to look at the geographical detail in five chapters of the Life that deal with Columba’s activities in the Inverness area.

It’s important to note that each chapter of the Life relates a separate event, and that they are ordered thematically rather than chronologically. I’m going to discuss them in the order they occur in the text, using Richard Sharpe’s excellent 1995 translation for Penguin Classics.

I’m also going to discard the ‘meat’ of each episode—the performance of Columba’s miracles—and focus only on the incidental topographical detail, which I’ll highlight in bold.

The monster in the River Ness

The first episode of note is Book II, chapter 27, in which Columba famously vanquishes a monster that lives in the depths of the River Ness (not Loch Ness!)

It begins:

Once, when [Columba] stayed for some days in the land of the Picts, he had to cross the River Ness. When he reached its bank, he saw some of the locals burying a poor fellow. They said they had seen a water beast snatch him and maul him savagely as he was swimming not long before.

Columba sends one of his monks, Luigne moccu Min, into the river, as bait for the beast:

The blessed man…astonished them by sending one of his companions to swim across the river and sail back to him in a dinghy that was on the further bank.

The beast takes the bait, rushing up from the riverbed to attack poor Luigne. The rest of the chapter is concerned with Columba’s overpowering of the beast, sending it back to the bottom of the river and (just) sparing Luigne’s life.

It’s a dramatic episode, but what concerns us are its prosaic aspects. If we ignore the miracle, we see that while visiting northern Pictland, Columba has to cross the River Ness, and it appears that his plan is to cross it by boat rather than at a ford.

Since most of Columba’s business in northern Pictland seems to involve visiting King Bridei, one conclusion might be that Bridei’s fort lay across the river from the approach from Iona. This is admittedly tenuous, but as we’ll see, it may have a bearing on the fort’s location.

The healing pebble from the River Ness

In II.33, Columba is in Bridei’s fort. He commands the king’s mage Broichan to release a female Gaelic slave before he (Columba) leaves the Pictish province, or Broichan will soon die. Broichan shows no intention of releasing the enslaved woman, and Columba duly departs.

Adomnán tells us:

…leaving the house, he came to the River Ness, where he picked up a white pebble.

This pebble, blessed by Columba, has the power to heal Broichan, who at that very moment is dying from a seizure (as Columba predicted). Messengers from Bridei’s fort arrive on horseback as Columba is explaining the power of the pebble to his companions. They take the pebble back to heal Broichan, who has been terrified by this experience into freeing the enslaved woman.

Here the topographical emphasis is again on the river, which is shown as being very close to the fort. We can tell this from the fact that messengers from the fort reach Columba shortly after he has picked up the pebble, and are able to take it back in time to stop Broichan from dying.

A weather battle on Loch Ness

In II.34, Columba is again in Bridei’s royal hall. Broichan threatens to disrupt the holy man’s return journey to Iona by summoning adverse weather that will prevent him from sailing home.

We are told that:

On the same day as he had planned in his heart, St Columba, with a great crowd of people following, came to the long loch at the head of the River Ness.

As Broichan had intimated, a mist has descended over the loch and the wind is blowing in from the south-west. Undeterred, Columba boards the boat and sails off into the wind. Before long, God intervenes to lift the bad weather:

In only a little time the contrary wind backed round, and, to everyone’s wonder, turned in their favour. And so all day they enjoyed a gentle following breeze, and the boat arrived at its intended destination.

The impression here is that Columba has been staying at Bridei’s fort, and that to get back to Loch Ness where his boat is, he must walk along the River Ness. This again places the fort in a close geographical relationship with the river.

The steep path to Bridei’s fort

In II.35, Columba arrives for the first time at Bridei’s fort, only to find that the “puffed-up” king has barred the gates against him. By making the sign of the cross on the gates, Columba gains entry and wins the king’s respect from that day onwards.

The part that concerns us here is:

…the first time that Columba climbed the steep path to Bridei’s fortress…

This tell us that Bridei’s fort was a hillfort, and not a promontory fort like Burghead in Moray, or a lowland enclosure like Rhynie in Aberdeenshire.

A pagan baptism in Glen Urquhart

A final glimpse of Columba in Inverness-shire comes in III.14. This seems to be a different visit from those outlined above, as it’s in a later part of the text and Columba is an old man.

It’s notable that the saint is not sailing this time, but (despite his advanced years) traversing the Great Glen on foot. Adomnán tells us that:

When Columba was travelling to the other side of Drum Alban, suddenly, at the side of Loch Ness, he was inspired by the Holy Spirit.

We then learn that God wishes Columba to convert a dying pagan who lives nearby.

St Columba…hurried on as fast as he could ahead of his companions, till he reached the fields of Glen Urquhart. There he found an old man called Emchath, who heard and believed the word of God preached to him by the saint, and was baptised.

This episode shows Columba approaching the Inverness area via Urquhart on the western shore of the loch (below). This may be significant when combined with the river-beast episode above.

Five topographical clues to the location of the fort

By removing the substance of Adomnán’s text, and focusing only on the incidental topographical details, we can note the following about Bridei’s fort:

It’s located up a steep path

It’s close enough to the River Ness for this to be a repeatedly-emphasised feature

It’s within reasonable walking distance from the head of Loch Ness

Columba gets there either by boat to the head of Loch Ness, or on foot via Glen Urquhart

It may lie to the east of the river, since at one point Columba has to cross the river

One thing I find striking about these episodes is that Adomnán’s geography of the Inverness area is surprisingly accurate. One might even say it’s unnecessarily accurate, given that elsewhere in the Life he uses generic scenery and doesn’t name the places where Columba’s miracles occur.

He describes Loch Ness as “the long loch at the head of the River Ness” and shows that it takes a day to sail from one end of it to the other. He knows that Urquhart is located beside the loch and that Glen Urquhart is good agricultural land. He implies that it does not take long to walk from the fort to the head of the loch, suggesting that he knows the river is short (just six miles).

We may also note the absences. Adomnán nowhere mentions the Beauly Firth or Moray Firth, and he does not have Columba cross to the Black Isle; an interesting omission if we wanted to imagine the monastery at Rosemarkie as a foundation dating to Columba’s time.

Instead, the action takes place around the loch and river, with Adomnán consistently locating the fort close to the river. Indeed, the Ness is the natural feature that he mentions most often.

My conclusion from all this is that Adomnán knew the area himself, and that his descriptions of the fort, while still vague, may carry more weight than Isabel Henderson presumed.

Three possible sites for Bridei’s fort

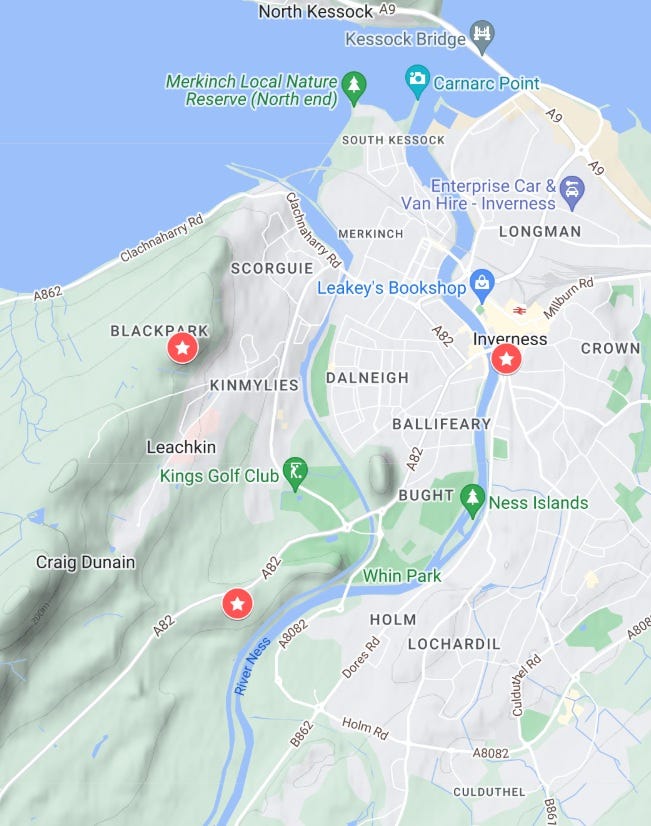

On that basis, three possible sites suggest themselves for the fort: Craig Phadrig, the Inverness castle hill, and Torvean. As we’ll now see, each has points in its favour and points against.

Site no.1: Craig Phadrig

Craig Phadrig has long been the favoured location for Bridei’s fort. An excellent written account of the site by Alison McCaig explains why. The fort has attracted antiquarian interest since the late eighteenth century, due to its prominence on a hill above Inverness, the visible remains of a vitrified fort at its summit, and its proximity to the city, which encourages outings to it.

As mentioned above, the report notes that the first documented link between Craig Phadrig and Bridei’s fort was made in the 1793 Old Statistical Account. Renewed support came from the first modern excavation of the site, by Alan Small and Barry Cottam in 1971–72. They discovered that it was built and abandoned in the Iron Age, but was re-occupied during the Pictish period.

There were signs that the fort was a high-status dwelling during its reoccupation. Small and Cottam found evidence of fine metalworking in the form of a mould for an escutcheon of a hanging bowl, as well as fragments of ‘E’ ware pottery, both dateable to the Pictish period.

Unfortunately, they only excavated a small area, and Alan Small’s death in 1999 meant that the findings were never properly written up. Small and Cottam’s notes and archive are sadly largely lost, precluding a posthumous reappraisal and re-dating exercise.

The wrong location for Bridei’s fort?

Although the E ware from Craig Phadrig is typically dated to the late sixth or seventh century, putting the fort into the right period, the site is not a very good fit with the location of the fort as described by Adomnán.

While it’s certainly up a steep path, it’s around two miles from the River Ness, and its outlook is north-westwards over the Beauly Firth (which Adomnán never mentions), rather than southwards towards Loch Ness.

Craig Phadrig is also not unique in producing evidence of high-status Pictish-era metalwork. As we’ll see, Torvean was the findspot of a massive silver chain linked to Pictish kingship.

However, as the only site with evidence of fine metalwork production, which also occurred at other elite Pictish sites, like Rhynie in Aberdeenshire and the King’s Seat at Dunkeld, Craig Phadrig may have a better claim to being a royal site. That said, it’s the only site of the three to have been excavated, and similar evidence at the castle hill and Torvean may await discovery.

Site no.2: Inverness Castle Hill

The second candidate is hiding in plain sight. The castle hill of Inverness rises steeply above the river in the city centre, its flattened top now occupied by a linked pair of castellated red sandstone buildings dating from the 1830s and 1840s.

The current building is only the latest to occupy the site, which has been in continuous use since records began in the twelfth century, and likely long before that. The Canmore record describes a long history of construction, conflict and destruction on the site, owing to its position at a strategic point dominating river access to the Great Glen and the Moray Firth.

Although the site has not been systematically excavated, Discovery and Excavation in Scotland vol. 22 reported that in 2020 and 2021 a series of trial pits dug at the castle by AOC Archaeology:

…revealed disturbed midden deposits at a depth of 5m below the ground surface, which included shell and animal bone and disarticulated human remains.

No dates have been recorded for these finds—if anyone knows of any, I’d love to hear about it.

A crossing over the Ness?

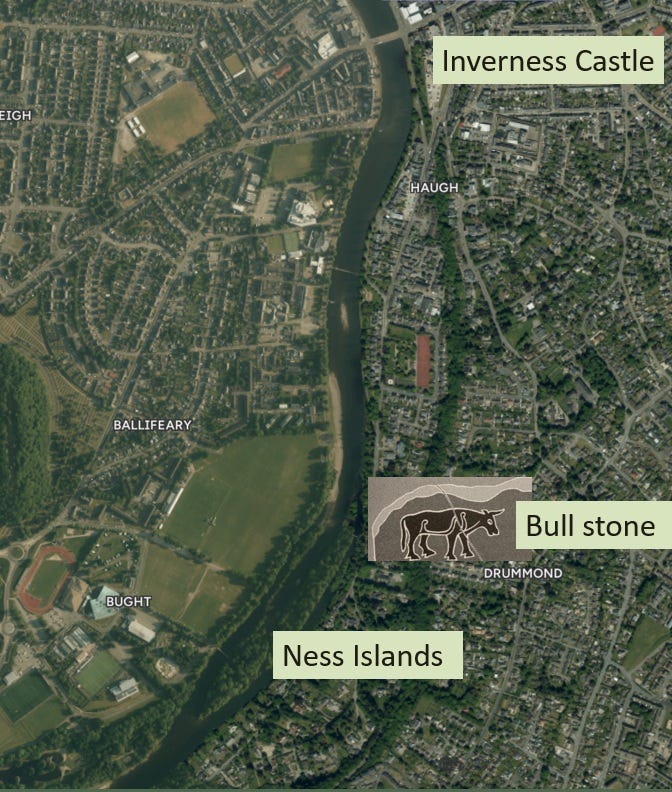

The castle hill’s position beside the Ness, and its strategic location in the wider landscape, make it a good candidate for Bridei’s fort. On that note, we may consider the faint hint in the Life that the fort lay on the other side of the river from the approach via Urquhart.

In my talk I proposed that approaching Inverness from the south, a good crossing point by boat might be the Ness Islands, where a Pictish stone with a bull carving was found in the nineteenth century. I’m grateful to Jonathan Wordsworth for advising me that this might not be the best place, as the river is deeper and thus more dangerous here. (Though that might make it a good place for a water beast to lurk!)

Class I Pictish stones have also been found at Knocknagael, Kingsmills and Cullaird, all to the east of the river. The Knocknagael stone was found close to the large Iron Age craftworking site at Culduthel. Together with the probable barrow cemetery at Allanfearn, around 3.5 miles from the castle hill, this suggests that late Iron Age/early Pictish elite activity was concentrated on the east side of the river. This may add further weight to the idea of Bridei’s fort on the castle hill.

Site no.3: Torvean

The unexcavated and ‘forgotten’ fort of Torvean, perched on a ridge above the west bank of the River Ness, has not often been proposed as the site of Bridei’s fort. However, of the three sites considered here, it’s the one that most comfortably fits Adomnán’s topographical descriptions.

Here is a fort that sits up a steep path, in close proximity to the river, a reasonable walking distance (c. 4 miles) from the head of Loch Ness, and easily approachable via Urquhart.

The fact that the Ness is the only body of water in the vicinity of this fort might also serve to explain Adomnán’s emphasis on the river, rather than the Beauly or Moray Firths, in the episodes set in and around Bridei’s fort.

Like the castle hill, Torvean is also in a strategic location, overlooking the narrow entranceway into the Moray Firthlands from the Great Glen.

Finds like the E ware sherds from Craig Phadrig suggest that the Great Glen was a trade route into northern Pictland from the busy Irish Sea zone and its onward connections to Gaul and the Mediterranean. Indeed, in II.33, we see Broichan drinking from a glass cup (vitrea); a high-status imported vessel. A fort at Torvean would be well placed to control trade into and out of the Glen.

The silver Pictish chain

The case for Torvean is strengthened by the fact that in 1807, workers digging the Caledonian Canal unearthed a massive silver chain, and perhaps other silver items, beneath the hill of Torvean. Jonathan Wordsworth has done some superb detective work to identify the spot.

Eleven such chains have been found across Scotland, and although only four were found in Pictland proper, the fact that two are decorated with Pictish symbols means they are considered to be Pictish, and to have been status symbols owned and worn by Pictish rulers.

In their book Scotland’s Early Silver: Transforming Roman Pay-Offs to Pictish Treasures, the National Museum’s Alice Blackwell, Martin Goldberg and Fraser Hunter write that:

At the time they were made the chains were the heaviest personal ornament ever seen in Scotland. Their scale…means they should be seen as a kind of regalia, rather than jewellery. Indeed the largest chain is almost twice as heavy as the Crown of Scotland, altered into its current form for James V in 1540.

It is very tempting to think that the massive chain found at Torvean is the kind of object that might have been kept in the ‘royal treasury’ (thesauris regis) that Adomnán says existed in Bridei’s fort (and in which the holy pebble that healed Broichan was kept). The NMS dates the manufacture of the chains to AD 300–500, but they may have remained in use for much longer.

To me, the proximity of the findspot of the chain to a riverside fort in a strategic location means Torvean has as much right as Craig Phadrig to be considered for the site of Bridei’s fort.

However, its small size may count against it. The internal area of Torvean measures just 465m2, making it tiny compared with Craig Phadrig at 2,500m2. If it was occupied in the Pictish period (and this is an unknown, as it has never been excavated), it might fit more comfortably as a guard post on a key route into and out of the Firthlands, rather than a royal citadel.

Conclusion: A new front-runner?

Having considered all three sites in light of the clues provided in Adomnán’s text, to my mind the most likely location for Bridei’s royal residence is the castle hill of Inverness.

Here is a large site dominating the river in a highly strategic location—described thus by the Alcocks, once they had dismissed Urquhart Castle as the site of Bridei’s fort:

Having given further consideration to the Castle Hill of Inverness, we now believe that its large size, dominating aspect rising about 25m above the river, and command of the lowest fording point on the Ness, all combine to make it eminently suitable to have been the principal stronghold of an important king.

Unlike Craig Phadrig and Torvean, the castle hill also sits amid a concentration of Class I Pictish sculpture and close to the late Iron Age craftworking centre at Culduthel—suggesting it was the most important place of the three sites in early Pictish times.

While we may never know for sure where Bridei’s fort was, I hope I’ve shown that both the castle hill and Torvean merit serious consideration, and that the castle hill perhaps deserves to oust Craig Phadrig as the front-runner. I’d be very happy to hear your thoughts.

References

Alcock, Elizabeth, and Leslie Alcock, ‘Reconnaissance excavations on early historic fortifications and other royal sites in Scotland, 1974-84. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 122 (1993): 215–87.

Alcock, Leslie. Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 2003.

Blackwell, Alice, Martin Goldberg, and Fraser Hunter. Scotland’s Early Silver: Transforming Roman Pay-Offs to Pictish Treasures. National Museums Scotland, 2017.

Discovery and Excavation in Scotland, vol. 22. Archaeology Scotland, 2021.

Henderson, Isabel. ‘Inverness: A Pictish Capital,’ in Hub of the Highlands: The Book of Inverness and District. Inverness Field Club, 1975, 91–108.

Mack, Alistair. Field Guide to the Pictish Symbol Stones. Pinkfoot Press,1997.

McCaig, Alison. Craig Phadrig, Inverness: Survey and Review. RCAHMS and the Scottish Forestry Commission, 2014.

Noble, Gordon, and Nicholas Evans. Picts: Scourge of Rome, Rulers of the North. Birlinn, 2022.

Peteranna, Mary, and Steven Birch. ‘Storm damage at Craig Phadrig hillfort, Inverness: results of the emergency archaeological evaluation,’ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 148 (2019): 61–81.

Sharpe, Richard (ed. and tr.). The Life of Saint Columba by Adomnán of Iona. Penguin Classics, 1995.

Small, Alan. ‘The Hillforts of the Inverness Area.’ In Hub of the Highlands: The Book of Inverness and District. Inverness Field Club, 1975, 78–90.

Wordsworth, Jonathan. ‘Torvean Silver Chain: Some Notes Derived from its Discovery.’ Highland Council Historic Environment Record, undated.

Wordsworth, Jonathan. ‘Torvean Hillfort, Inverness: Managing a Forgotten Site.’ NOSAS Blog, 11 November 2018.

My work desk for a few years was at the top of the older building of the castle, at a window with a view up the river (and cold from the wind down the river). So I'm biased, but generally happy with your thinking 😃 The chain does seem to be strong counter evidence, though.

Your theory makes sense to me! But mainly what I love about this is that it sounds as if the people who thought there wasn't much evidence just weren't paying attention properly, and you WERE \o/