Did ‘vikings’ conquer Moray in the 9th century?

Or was it a twelfth-century geographical misunderstanding?

NOTE: This post has involved a lot of research and help from other people. I’m grateful to Richard Campbell-Howes, Christine Clerk, Tom Fairfax, Alan G. James, Jake King, Gordon Noble and Alex Woolf for kindly answering various questions I had. Any errors are mine alone.

One myth that clings to modern-day Moray is that in the ninth century the region was conquered and at least partly settled by ‘Vikings’.

Indeed, if you go to the tourist information website for Burghead, the site of a huge Pictish promontory fort on the Moray Firth coast, you’ll find this myth presented as fact—complete with a date and the name and title of the Norse conqueror:

…in 884 A.D. Sigurd the Powerful captured Torridon by which name Burghead was known at that time. Sigurd, Earl of Orkney was the leader of the first expeditions of Vikings.

On the surface of it, this sounds like solid knowledge. But when you dig deeper, that solidity quickly begins to crumble.

There’s a lot to unpack in the visitor centre’s claim, and I can’t do it all in one post. So for this one I’m just going to look at some of the evidence for and against the idea that a ninth-century Earl Sigurd the Powerful of Orkney conquered territory in Moray.

It involves digging into one of the most problematic sources of early medieval Scottish history—the late twelfth/early thirteenth-century Orkneyinga Saga, produced in Iceland by an unknown author who compiled the narrative using a mixture of oral tradition and a number of (lost) written sources.

(Since we don’t know the identity of this author, I’m going to refer to them as ‘they’ in this blog, rather than automatically assuming they were male.)

Sigurd the Powerful: A ninth-century earl of Orkney?

So… Sigurd the Powerful. At first glance, he seems to have been a real historical figure and indeed the first earl of Orkney. A Norwegian by birth, he appears several times in the Icelandic sagas, most prominently in chapters 4 and 5 of Orkneyinga Saga.

Chapter 4 relates how Harald Fairhair (r. c.872–930), king of a newly-unified Norway, granted Orkney and Shetland to Rognvald earl of Møre, but Rognvald re-gifted them to his brother Sigurd.

All three—Harald, Rognvald and Sigurd—had been on a mission to recapture the islands from a band of renegade vikings who had been using them as a base to attack western Norway. The saga (in the Penguin Classics version translated into English by Herman Pálsson and Paul Edwards in 1978) says that:

When the king sailed back east he gave Sigurd the title of earl and Sigurd stayed on in the islands.

When might this have happened? Events in Orkneyinga Saga aren’t dated, but another Icelandic saga, Landnámabók (the Book of Settlement), says that Sigurd ruled in Orkney at the same time as Louis the German (r. 843–876) in Germany and Alfred the Great (r. 871–886) in Wessex. This led the historian Professor Barbara E. Crawford to date the creation of the earldom to roughly 870 AD.

Chapter 5 is the one with the most information about Sigurd. It tells two stories: one about a military alliance with a certain Thorstein the Red, and a longer one about a battle with one Máel Brigte, an ‘earl of the Scots,’ as a result of which Sigurd meets a death worthy of a Darwin Award.

Here’s what we’re told about the alliance with Thorstein the Red:

Earl Sigurd became a great ruler. He joined forces with Thorstein the Red, the son of Olaf the White and Aud the Deep-Minded, and together they conquered the whole of Caithness and a large part of Argyll, Moray and Ross. Earl Sigurd had a stronghold built in the south of Moray. [my emphasis]

The final sentence above is the only information anywhere in the sagas about Sigurd having a fort in Moray, and I’ll come back to it later.

Sigurd’s legendary—and unfortunate—death

But first, the story Sigurd is famous for: his battle with Máel Brigte and its legendary aftermath. Following on directly from the sentence above, we read that:

A meeting was arranged at a certain place between him [i.e. Sigurd] and Maelbrigte, Earl of the Scots, to settle their differences. Each of them was to have forty men, but on the appointed day Sigurd decided the Scots weren’t to be trusted so he had eighty men mounted on forty horses.

To cut a short story shorter, when Máel Brigte rumbles the fact that Sigurd has brought 80 warriors, he tells his men to try to kill at least one man each before they’re inevitably killed themselves.

Sigurd in turn rumbles this strategy and counter-strategises accordingly, telling half of his men to dismount and fight on foot, and the other half to ride their horses straight at Máel Brigte’s men to break their ranks. The compiler then tells us:

There was a fierce fight, but it wasn’t long before Maelbrigte and his men were dead. Sigurd had their heads strapped to the victors’ saddles to make a show of his triumph, and with that they began riding back home, flushed with their success.

But the flush of success was to be short-lived, because dead Máel Brigte had one more ace to play:

On the way, as Sigurd went to spur his horse, he struck his calf against a tooth sticking out of Maelbrigte’s mouth and it gave him a scratch. The wound began to swell and ache, and it was this that led to the death of Sigurd the Powerful. He lies buried in a mound at Ekkialsbakki.

It’s a great story, and it does suggest that a ninth-century earl Sigurd of Orkney came to blows with an earl from the Scottish mainland, presumably because he and Thorstein had encroached on the earl’s territory by ravaging “a large part of Argyll, Moray and Ross”.

But is any of it historically reliable, and if so, how much?

Were Sigurd and Thorstein real people?

It’s something historians have long debated, but the recent scholarship generally falls somewhere between none of it is reliable and some of it is reliable.

Dr Alex Woolf, for example, describes the pre-1100 events recounted in Orkneyinga Saga as “largely a work of fiction.” He notes that of all the people mentioned in chapter 5, only one can also be found in contemporary Irish and Scottish sources: Thorstein the Red’s father Olaf the White.

This Olaf seems to correspond with Olaf, king of Viking Dublin, who appears numerous times in Irish and Scottish sources during the period 853–871. If the two Olafs are the same person, as they seem to be, this also helps to place the events of Chapter 5 in the last quarter of the ninth century.

However, no Irish, Scottish, Welsh or English source mentions a Thorstein the Red, an Aud the Deep-Minded, a Sigurd earl of Orkney, or a Máel Brigte ‘earl of the Scots’ in this period.

In a way that’s not surprising, as apart from the Icelandic sagas, there are no written sources at all for the far north of Scotland in the ninth century. But if Thorstein is the son of the king of Dublin, his absence from the Irish annals is at least slightly suspicious—especially if he and Sigurd conquered the whole of the north of Scotland from Caithness down into Moray, as Orkneyinga Saga claims.1

Norse conquest of Moray: Place-name evidence

But absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. So if we assume Sigurd was real, despite not appearing in any Insular (i.e. British and Irish) sources, how else might we know that he conquered territory in Moray?

One way would be to look for place-name evidence. But when we look for Old Norse place-names in Moray, there’s nothing solid to be found. There’s the Moray Firth (O.N. fjǫrðr, a fjord) itself, of course, and the Halliman and Covesea Skerries (O.N. sker, a rocky islet) off the coast of Lossiemouth, but these are maritime navigational features, not settlements.

Given the flatness of the land, Surradale and Philaxdale north of Elgin are more likely to be Gaelic dail (meadow) than Old Norse dalr (valley), though if it was Gaelic I’d expect the dal element to come first, so I’d welcome views on this.

The historian Professor Geoffrey Barrow thought he could see the Norse word gata (road) in the name Budgate near Cawdor in Nairnshire, but the earliest recorded forms of this name, and its local pronunciation ‘boo-jit,’ suggest a Brittonic (i.e. Pictish) root; perhaps bod-gwid (wood-house).2

There’s also a magnificently detailed 1783 map of the now-drained Loch Spynie north of Elgin, showing islets called Papies Holm, Skerries Holm, Mid Holm, Wester Holm and others, all seemingly from Old Norse holmr (islet).3 This is intriguing to say the least—and if anyone has any thoughts I’d be glad to hear them—but these are also navigational features, not settlement names.

Things are different in Ross, incidentally. It has numerous Scandinavian place-names, most notably Dingwall, which inarguably comes from the Old Norse þingvöllr, meaning assembly site or moot hill. (In echoes of the search for Richard III, this assembly site was discovered in 2012 under the Cromartie car park in the town.)

It’s true that Ross was part of both the medieval bishopric and the medieval earldom of Moray, so technically these Norse names in Ross could be said to lie in a kind of ‘greater Moray.’ But the saga author differentiates between Moray and Ross, so we have to assume that by ‘Moray’ they specifically meant the land stretching eastwards from Inverness along the Moray Firth coast.

Norse conquest of Moray: archaeological evidence

The other big indicator of Norse settlement is archaeology. But again, archaeological evidence for Scandinavian settlement of any kind in Moray is virtually non-existent.

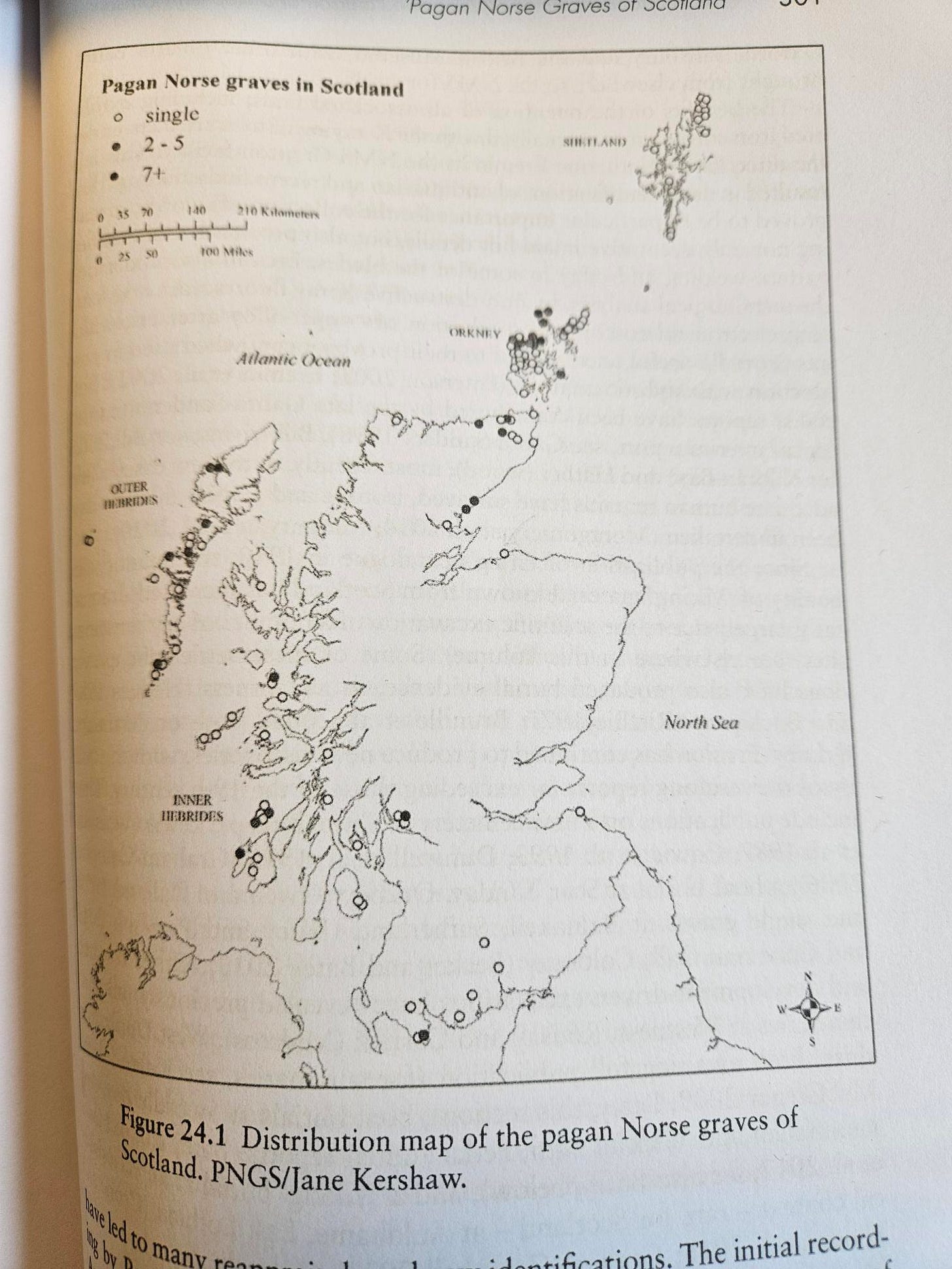

I did spend half a day chasing after a ‘pagan Norse grave’ at Burghead marked on the below map in a new (and excellent but punitively-priced) book called The Viking Age in Scotland: Studies in Scottish Scandinavian Archaeology – one in a forthcoming catalogue of such graves to be published by the Pagan Norse Graves of Scotland project headed up by Professor James Graham-Campbell.

This felt like it could be evidence in favour of Sigurd having occupied the fort at Burghead, as the visitor centre claims, but information about this grave is hard to come by. Nineteenth-century excavations at Burghead by Hugh W. Young did reportedly turn up a number of graves, but they were considered at the time to be Christian, since they contained white pebbles in the shape of a cross.4

If anyone knows anything about the grave marked on the above map, I’d love to hear it.

A reflection of twelfth-century geopolitics?

So far then, the evidence for Norse conquest and settlement of Moray in the ninth century is looking pretty threadbare. And indeed, some historians view Sigurd and Thorstein’s alleged conquests not as historical ninth-century fact, but as a back-projection of the political scene in northern Scotland at the time when Orkneyinga Saga was compiled, around 1200.

The regional names Moray and Ross, for example, belong to later medieval times. As far as anyone can tell, in the ninth century both areas were part of the old Pictish kingdom of Fortriu, with the name ‘Moray’ first appearing in surviving sources in the period 943–954 AD. Could the author’s use of these ‘modern’ territorial names hint at contemporary rather than ninth-century concerns?

Alex Woolf suggests in his book From Pictland to Alba 789–1070 that the description of Sigurd and Thorstein’s conquests as including Ross and Moray is a reflection of the expansionist aspirations of Harald Maddadsson, earl of Orkney and Caithness from 1158–1206.5

Harald and his allies among the northern aristocracy had tried to wrest control of Moray and Ross from the Canmore kings of Scotland throughout the second half of the twelfth century, and his alliance with Somerled, lord of the Isles—an area that included Argyll—may be echoed in the saga figure of Thorstein the Red.

So in this scenario, the claim that Sigurd and Thorstein had conquered a large part of Argyll, Moray and Ross in the ninth century may be an attempt on the author’s part to legitimise Harald’s claim on those lands in his own time.

But there may be a more prosaic reason why the author of Orkneyinga Saga claimed that Sigurd and Thorstein conquered land in Moray—and it comes down to a single place-name.

The smoking gun: the place-name Ekkialsbakki

The smoking gun is the author’s use of the place-name Ekkialsbakki. This is generally accepted to mean the northern bank of the River Oykel (Ekkial), and by extension, the northern shores of the Kyle of Sutherland and the Dornoch Firth—outlined in red in the map below.

This shoreline forms the border between Sutherland and Ross, making it a geopolitically significant feature of northern Scotland. Despite this, it’s only used four times in the whole of Orkneyinga Saga, and saga scholars have noted that the compiler always seems to place it somewhere else: not at the Oykel or Dornoch Firth, but in a vague location on the southern shore of the Moray Firth.

To see what they mean, let’s look at the four times Ekkialsbakki appears in the saga.

Chapter 5: Sigurd’s burial-place

The first mention is in Chapter 5, regarding Sigurd the Powerful’s burial place:

On the way [home], as Sigurd went to spur his horse, he struck his calf against a tooth sticking out of Maelbrigte’s mouth and it gave him a scratch. The wound began to swell and ache, and it was this that led to the death of Sigurd the Powerful. He lies buried in a mound at Ekkialsbakki.

Admittedly, we don’t get any immediate idea here of where the author imagines Ekkialsbakki to be, other than it seems to be at or near Sigurd’s home, since that’s where he was heading when the tooth scratched him.

However, as the author believed that Sigurd had a fort in Moray, they may have imagined that the mound at Ekkialsbakki was near this fort. (I’ll come back to this in my next blog.)

Chapter 20: The battle of Torfnes

The second instance is in Chapter 20, which intersperses saga narrative with fragments of skaldic verse. It concerns two battles between an eleventh-century earl of Orkney, Thorfinn the Mighty, and a king of Scots called ‘Karl Hundason,’ whom historians tend to identify with Macbeth (r. 1040-1057).

The first battle, a sea-battle, is clearly and vividly described as taking place off Deerness on the east side of Mainland Orkney. The location of the second, a land-battle, however, is confusing.

The author writes:

They faced each other at Torfnes on the south side of the Moray Firth.

The interpolated skaldic verse, meanwhile, says:

Well the red weapons

Fed wolves at Torfnes

Young the commander who

Created that Monday-combat

Slim blades sang there

South on Oykel’s bank

Fresh for the fray, he

Outfaced the Scots’ king

So here, the verse states that Torfnes is located ‘south on Oykel’s bank,’ which has led historians to identify it as Tarbat Ness in Easter Ross. But in the narrative, the author describes the battle as happening ‘on the south side of the Moray Firth.’ As the verse is a pre-existing fragment that has been incorporated into the saga, has the author misunderstood where ‘Oykel’s bank’ is?

The same confusion persists in the two remaining mentions of Ekkialsbakki, in chapters 74 and 78. These chapters are set between 1130 and 1155 and feature Svein Asleifarson, an old-school ‘viking’ who spends half his time farming on Gairsay in Orkney and the other half raiding and plundering in Wales and Ireland.

Chapter 74: Svein takes Earl Paul to Atholl

One of Svein’s skills is sneaking up on people unnoticed, and in chapter 74 there’s a clear description of a route he takes to sneak up on Earl Paul of Orkney, whom he is aiming to take captive:

Svein exchanged his ship for a cargo-boat and put out [from Thurso] with thirty men aboard. He had a north-westerly wind as he sailed across the Pentland Firth, hugging the west coast of Mainland [Orkney] as far as the Eynhallow Sound, then along the Sound and home to Rousay.

This journey is easy to follow on a map, suggesting the author is familiar with the geography of Caithness and Orkney. But once Paul has been captured (at Westness on Rousay), the itinerary becomes confusing as Svein heads back south to the Scottish mainland:

They… sailed the same way back west to Mainland [Orkney], right between the Hoy and Graemsay, then east of the Swelchie [a whirlpool off the north-east tip of the island of Stroma] into the Moray Firth, and right up the Firth to Ekkialsbakki. There Svein left his ship with twenty men in charge, taking the rest of them with him to Atholl.

Here, the phrase ‘right up the Firth’ seems at odds with the landing-place being the northern bank of the Oykel or the Dornoch Firth. The author surely means that Svein sails all the way to southern shore of the Firth, where they seem to believe Ekkialsbakki is. That would be a more sensible landing place for an onwards overland journey to Atholl, presumably via the Spey or the Findhorn.

Chapter 78: Svein catches Olvir and Frakokk unawares

This interpretation is strengthened by the fourth and final instance of Ekkialsbakki, which appears in chapter 78 in an even more confusing itinerary.

Here, Svein is sneaking up on a couple called Olvir and Frakokk, whom he means to kill in revenge for killing his father. Olvir and Frakokk are at their farm in Helmsdale in Sutherland, but they have “posted spies in every direction from which they might expect trouble from Orkney.”

In order to outwit them, Svein takes the following route:

…sailing south as soon as he was ready to the Moray Firth with a north-easterly wind as far as Dufeyrar [usually taken to be Banff, but Joseph Anderson suggested Duffus], a market town in Scotland.

From there he made his way beyond Moray to Ekkialsbakki, then on to Atholl where Maddad provided him with guides who knew the mountain and forest route he might choose. From Atholl he travelled by forest and mountain above all the settlements till he reached Helmsdale in the centre of Sutherland.

Here there’s even less reason to believe that the author means the northern shore of the Dornoch Firth or the Oykel here when they write Ekkialsbakki.

Firstly it would take Svein back north-west towards Sutherland, risking his being observed by Olvir and Frakkok’s spies—the very thing he is trying to avoid.

Secondly, if Svein is going to Atholl via Banff—itself a strange detour if Atholl is his destination, strengthening the idea that Dufeyrar is not Banff but Duffus, as Joseph Anderson suggested—why would he sail back north to the Dornoch Firth before continuing his journey by land?

Thirdly—and this is where things get quite nerdy—there is another version of Orkneyinga Saga, the so-called ‘O’ version, held in the Royal Library in Stockholm, which adds a bit more detail to this itinerary.6 It says:

…sailing south as soon as he was ready to the Moray Firth with a north-westerly wind as far as Dufeyrar, a market town in Scotland. From there he made his way beyond Moray to Ekkialsbakki, where lies Elgin, then on to Atholl... [my emphasis]

So as far as the ‘O’ version is concerned, there’s no doubt that Ekkialsbakki is on the south shore of the Moray Firth, because it’s where Elgin is.

Looking at these different itineraries on a map shows how odd Svein’s journey would be if he did go to Atholl via the Dornoch Firth. Below I’ve marked the itinerary via Dornoch in red, the itinerary via Dufeyrar/Banff and a supposed Moray Ekkialsbakki (here the mouth of the Spey) in green, and the itinerary via Dufeyrar/Duffus (at this time a harbour on the sea-loch of Spynie) and Elgin in purple.

Ekkialsbakki confusion: the source of the ‘Moray conquest’ myth?

So there’s good reason to believe that, as scholars have pointed out, the compiler of the saga thought that Ekkialsbakki was on the southern shore of the Moray Firth.

This is a crucial point when we consider the lands that the saga says Sigurd and Thorstein conquered in the ninth century:

Earl Sigurd became a great ruler. He joined forces with Thorstein the Red, the son of Olaf the White and Aud the Deep-Minded, and together they conquered the whole of Caithness and a large part of Argyll, Moray and Ross. Earl Sigurd had a stronghold built in the south of Moray.”

However, another of the Icelandic sagas, Heimskringla (Saga of the Kings of Norway), presents a much more conservative estimation of Sigurd and Thorstein’s conquests:

Then Thorstein the Red, son of Olaf the White and Aud the Deep-Minded, joined forces with [Sigurd]. They raided in Scotland and gained Caithness and Sutherland, right as far as Ekkjalsbakki.

In his 1935 PhD thesis on the saga, Alexander Taylor deduces that both the compiler of Orkneyinga Saga and the writer of Heimskringla, Snorri Sturluson, were using some of the same sources, but they were based in different regions of Iceland and did not collaborate.7 He identifies a lost Saga of Turf-Einarr as the common source for their information about Sigurd and Thorstein.

Given the way the information is presented in both sagas, it’s possible that this Saga of Turf-Einarr described the conquests of Sigurd and Thorstein as encompassing northern Scotland as far south as Ekkialsbakki.

If that’s the case, Snorri correctly interpreted this to mean the area covering Caithness and Sutherland. But the Orkneyinga Saga compiler, believing Ekkialsbakki to be on the shore of the Moray Firth—and maybe also having Harald Maddadsson’s recent exploits in mind—wrote that the pair conquered “a large part of Argyll, Moray and Ross.”

Given the lack of corroborating textual, archaeological and place-name evidence, it seems at least plausible that this is the source (or at least a source) of the idea that ‘vikings’ conquered Moray in the ninth century.

Coming in part II: Ekkialsbakki and Sueno’s Stone

When I started writing this post, it was going to be about Sueno’s Stone, and William Forbes Skene’s idea that the stone tells the story of Sigurd’s battle with Máel Brigte of Moray. Skene had his own theory about the location of Ekkialsbakki based on that interpretation. But it’s taken so long to set the scene that that will have to come in the next blog!

As always, thank you for coming on this research journey with me, and if you have any thoughts I would love to hear them.

References

Anonymous Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. The Early Church and the Loch of Spynie in Morayshire (c. 2018)

Clerk, Christine. Burghead, Moray: A history of archaeological thought. MSc dissertation, University of Aberdeen (2019)

Crawford, Barbara E. The Northern Earldoms: Orkney and Caithness from AD 870 to 1470. (2013)

Hjaltalin, Jon A. and Gilbert Goudie (trs). Orkneyinga Saga (translated into English with an introduction by Joseph Anderson (1873)

Horne, Tom, Elizabeth Pierce and Rachel Barrowman (eds). The Viking Age in Scotland: Studies in Scottish Scandinavian Archaeology. Edinburgh University Press (2023)

Kinnaird, Hugh and James Ainslie. Map of the Loch of Spynie and adjacent grounds (1783)

Pálsson, Herman and Paul Edwards (trs). Orkneyinga Saga: The History of the Earls of Orkney. Penguin Classics (1978)

McDonald, R. Andrew. ‘Soldiers Most Unfortunate’: Gaelic and Scoto-Norse Opponents of the Canmore Dynasty, c.1100–c. 1230, in History, Literature, and Music in Scotland, 700-1560 (2002)

Nordal, Sigurðr (tr). Orkneyinga saga (translation into Danish) (1916)

Skene, William Forbes. Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban, Volume 1, Second Edition (1886)

Taylor, Alexander Burt. A Study of the Orkneyinga Saga with a New Translation. PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh (1935)

Woolf, Alex. From Pictland to Alba 789–1070. Edinburgh University Press (2007)

Thanks to Linda Sutherland for pointing out that Thorstein is a key figure in the genealogies of the early Norse settlers of Iceland, and as such surely did exist - although his conquests in Scotland may well be exaggerations.

My thanks to Jake King and Alan G. James for sharing their thoughts on this place-name in the Scottish Place-Names Facebook Group, and to my uncle Richard Campbell-Howes for confirming the local pronunciation.

These islet names were first brought to my attention by an essay written by an anonymous Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, called The Early Church and the Loch of Spynie in Morayshire.

My thanks to Gordon Noble and Christine Clerk for their help tracking down this reference to a pagan Norse grave at Burghead.

My thanks to Alex Woolf for discussing this further with me on Facebook.

See footnote 13 on p 197 of Sigurðr Nordal’s 1916 translation of Orkneyinga Saga into Danish.

My thanks to Tom Fairfax for bringing this thesis to my attention on Facebook.

I am just as nerdy as you, which is probably why I found this your most exciting blog post so far! Obviously Sigurd's death is my favourite bit (and it seems so specific that I find it hard to believe that there is NO truth in it) but I love all the placename misunderstandings... although when you say "This journey is easy to follow on a map", I agree that it is, but I always find when I read your blog posts that I need to open a map immediately (and today was an extreme example of this)... and then I spend the whole time going "argh, why can't I remember which bit is the Pentland Firth, that name is so familiar... ARGH, I'm an idiot, of course it's THAT bit". ARGH.