Book Review: Picts: Scourge of Rome, Rulers of the North

A comprehensive new survey of Pictish history and archaeology is engaging, authoritative and absorbing for academics and amateurs alike

Picts: Scourge of Rome, Rulers of the North

By Gordon Noble and Nicholas Evans

Birlinn, 2022 - RRP £22

Writing the history of the Picts – the “last major ethnic group to disappear from Britain and Ireland,” according to this superb new book – has often been a process of creative destruction.

As modern analysis of the textual sources has revealed them to be less and less reliable, historians of the Picts have usually had to dismantle what’s been written before, rather than building on it.

While progress is still possible using the few reliable sources we do have, most of the advances in our understanding of life in northern Scotland in the first millennium AD are being led by archaeology.

Now, the scale of those advances is stunningly laid out in this new book from two leading academics; Gordon Noble, Professor of Archaeology at the University of Aberdeen, and his colleague Dr Nicholas Evans, a historian focusing on the medieval Celtic-speaking societies of Britain and Ireland.

A “broad and detailed introduction to the Picts”

While the title may seem to promise a new history of the Picts, the authors are quick to point out that their aim is “to provide a broad and detailed introduction to the Picts and their ways of life, emphasizing the archaeological evidence.” (my emphasis).

The result is a glorious sandwich of a book, with two chapters focusing on what we know of Pictish history enclosing five chapters devoted to exploring – and, crucially, connecting – the archaeological evidence for the Picts from across Scotland.

It covers an immense amount of ground, with the two historical chapters (1 and 7) providing a solid overview of the Picts from their emergence as a single group during the Roman occupation of southern Britain, to their eventual and much debated “disappearance” during the Viking Age of the 9th and 10th centuries.

Here, Evans’s own work is complemented and informed by up-to-date scholarship from historians including James Fraser, Alex Woolf and Gilbert Márkus, whose books the authors recommend to readers who seek “more detailed considerations of the historical evidence.”

The central five chapters take a thematic approach, presenting established and newly-discovered archaeological evidence for everyday life in Pictland; power, warfare and kingship; religion and the coming of Christianity; burial and commemoration practices; and symbols and writing.

These chapters are extremely rich in detail and meticulously and rigorously sourced, in many cases to the very latest scholarship and even some forthcoming works. The result is an enormous bibliography spanning history, archaeology, linguistics, art history, literary criticism, place-name studies, and probably more.

That makes this book a superb entry point into early medieval Scottish scholarship, and I’ve no doubt readers will find their Amazon wishlists ballooning.

Broad geographical scope – from Fife to Shetland

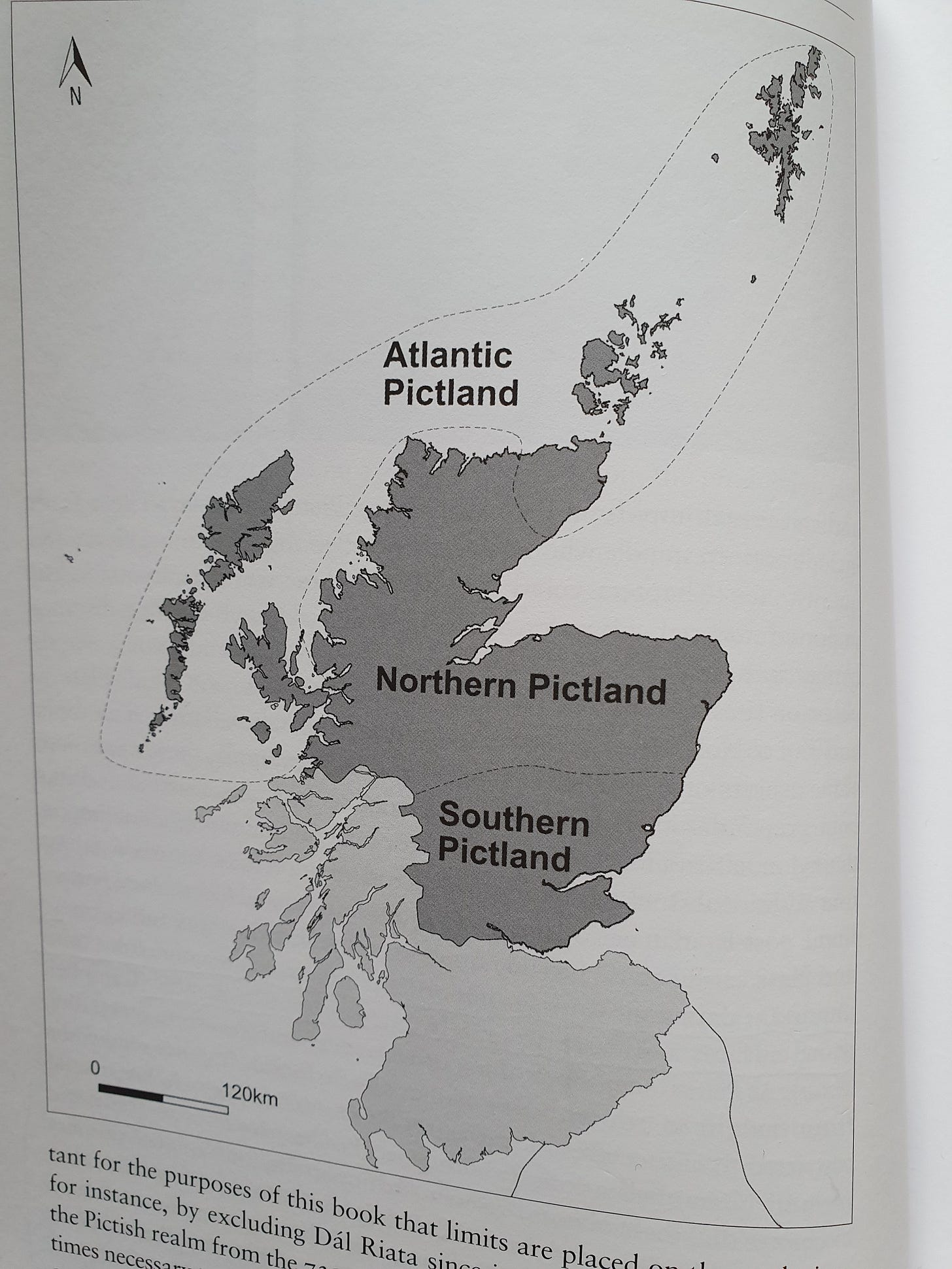

Unlike the authors’ previous book The King in the North (2019), which focused mostly on Moray and Aberdeenshire, this book surveys the whole of Pictland as we understand its geographical reach. In each chapter, Pictland is divided into three geographical regions – southern, northern and Atlantic Pictland – with each being given more or less equal treatment.

Coverage of well-known Pictish sites like Rhynie in Aberdeenshire and St Vigeans in Angus is complemented with a wealth of detail on lesser-known sites and finds, meaning that even seasoned Pictophiles will find something new and absorbing here.

To give just one example of personal interest to me, the authors find space to devote to a site at Congash, near Grantown on Spey, where, unusually, two non-Christian Pictish symbol stones mark the entrance to a small site presumed to be an early Christian chapel.

Joining the dots to shed new light on Pictland

One of the major strengths of this book is that it seeks to join the dots between archaeological sites that have usually been studied in isolation. The number of excavated sites has now reached the point where lines can be tentatively drawn and broad historical processes discerned – even if dimly.

One of my growing fascinations is with the links between secular and ecclesiastical power centres in later Pictland, for example. This book rewards that interest with the beginnings of new thinking on the links between the huge promontory fort at Burghead and the enormous and largely unexcavated ecclesiastical site at nearby Kinneddar, which appears to have strong royal connections.

In southern Pictland, similar tentative linkages are made between Clatchard Craig and Abernethy, Logierait and Rait, and Fortingall and Caisteal mac Tuathal, with the sense that there is a lot more to be discovered about the nature of the relationships between these and no doubt other “pairs” of sites.

Joining the dots in this way is starting to shed new light on long-term processes including the Christianisation and Gaelicisation of Pictland and the Scandinavian settlement of Atlantic Pictland.

The book also shows how advances in archaeological science are revealing more about population mobility and cultural interplay in the first millennium, bringing into sharper focus a Pictland that, over its c. 600-year span, became “increasingly multi-lingual and multi-ethnic.”

Untangling the mystery of the Pictish symbols

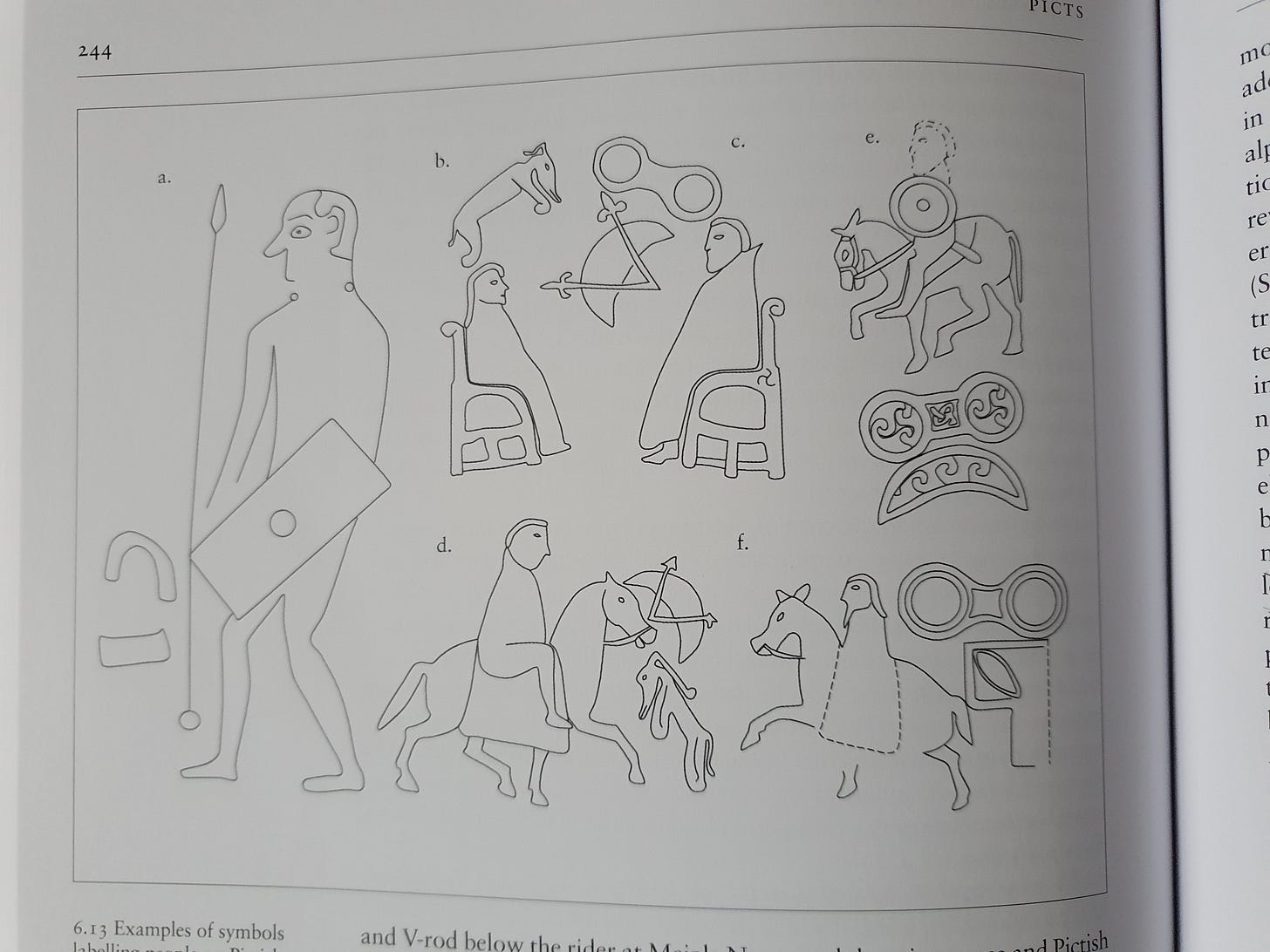

The multi-cultural nature of later Pictland was likely a major factor in two of its most enigmatic puzzles: the loss of the Pictish language and the meaning and function of the Pictish symbols, which endured unchanged for centuries but never really expanded outside the core Pictish territories.

On the latter point, the authors provide a solid overview of the genesis and decline of the symbols, using the latest dating evidence to place the start of the tradition in the Roman Iron Age and drawing on historical and archaeological evidence – such as the lack of symbols on the c. 820 AD Dupplin Cross – to posit an end date in the early ninth century.

Whatever their function – the book leans towards the marking of names or identities – the symbols are cast as unexportable outside Pictland, with the authors observing that “when Argyll was conquered in the 730s it did not lead to the adoption of symbols in that region other than at the major hillfort at Dunadd.”

Three minor niggles

I believe it’s the done thing to include in book reviews things that don’t work so well. Although this is an insignificant quibble for me personally, some people may be – at least initially – disappointed to discover that this is not quite the book promised by the title.

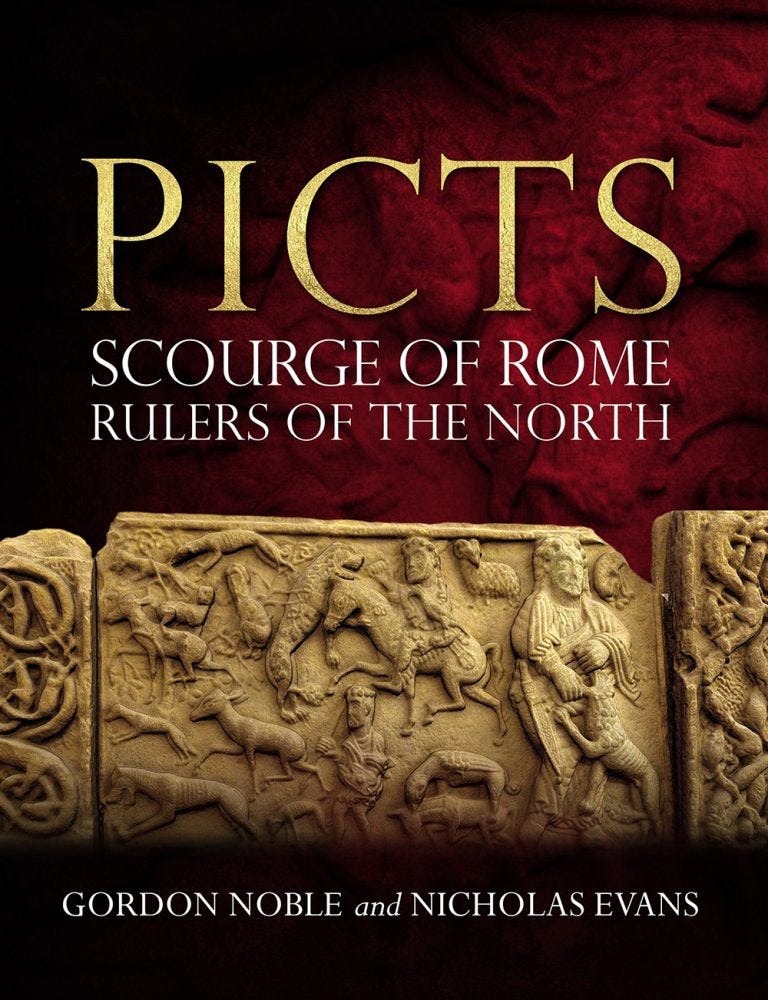

The publisher Birlinn is clearly aiming for the popular history market, with a sensationalist title and cover design casting this as a conventional history of the Picts, and in particular their relationship with the Roman Empire.

While the Picts certainly did give the Romans some localised trouble, and participated in the “Barbarian Conspiracy” of 367 AD, they were hardly a “scourge” in comparison with some of the other peoples the Romans colonised as they expanded their huge frontier. And the vast majority of the Pictish period is sited after the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain, between 400 and 900 AD.

As an editor myself, I might also remark that there are quite a few typos in the book – but this again is an extremely minor quibble and more a reflection on the publisher than the authors.

Lastly, I was slightly disappointed not to learn more about the discoveries at Burghead, where Gordon Noble has been leading a major excavation since 2015, but on that score I think I will just have to be patient!

An inspirational book that points the way forward for Pictish studies

Overall, this book is a major landmark in documenting the history of the Picts; an endeavour that sometimes feels more like taking two steps back than one step forward. Its many maps and illustrations bring the immense amount of historical and archaeological detail to life, and the authors successfully walk the difficult line between academic rigour and popular appeal.

Gordon Noble in particular seems to enjoy puncturing his more academic writing with engaging and down-to-earth asides, such as the observation that “disappointingly for archaeologists most early medieval buildings appear to have been kept very tidy” and the interpretation of a leather shoe discovered at the hillfort of Dundurn as “like slippers for a high-status Pict at leisure time.”

This engaging and readable but rigorous approach makes this book an essential purchase (and ideal Christmas present!) for the academic and amateur Pictophile alike, and well worth the £22 cover price.

And while on one hand it celebrates how far we’ve come in our understanding of the Picts, it also shows how far there is still to go. As such I’ve no doubt it will inspire new generations of archaeologists and historians to follow in the impressive footsteps of Gordon Noble and Nicholas Evans, and help to shed further light on this fascinating period of medieval Scottish (and British) history.