Kinneddar: Fragmentary hints of a royal Pictish monastery

In which I try to work out if an early medieval site near Lossiemouth is related to Sueno’s Stone

I’ve said before that my favourite thing about early medieval Scotland is that you have to draw on lots of different disciplines to try to piece its history together.

With very few written records from before the 11th century, most of the information has to come from archaeology, art history, place-names, geology, geography, and comparison with other, better-documented places and times.

For my MA I’m trying to build up a picture of what was happening in Moray around 850-950 AD: the time period when art historians estimate Sueno’s Stone was put up. I want to try to put Sueno’s Stone into its local context, and that means looking at other contemporary sites in the area and trying to work out the relationships between them.

(None of this is easy, otherwise historians would have done it long ago. In fact they often say it’s impossible, although archaeologists are more optimistic – and the University of Aberdeen’s Northern Picts Project in particular has made enormous progress in the last decade or so.)

Kinneddar: A major early medieval monastic site

One such site is Kinneddar – today an unassuming field on the southern edge of the coastal town of Lossiemouth.

Nothing about this modern landscape setting hints that this was once the site of a huge early medieval monastery; the biggest yet discovered in northern Pictland, with its surrounding vallum (bank and ditch) enclosing up to 8.6 hectares of land.

It’s a site that saw continuous ecclesiastical use for over a thousand years: from its foundation in the 7th (perhaps even the 6th) century right through to 1669, when Kinneddar was merged with the neighbouring parish of Ogstoun and its church demolished. Even then, its graveyard (which is to the right in the above picture, behind the road signs) and manse continued to be used.

For a brief period from 1187-1207, Kinneddar was even the seat of the bishop of Moray. At that time it comprised a ‘cathedral’ – in reality a modest stone church – and a ‘palace’, rumoured to have been an impressive hexagonal building, but according to a geophysics survey carried out at the site, more likely to have been a rectilinear building like the 14th century bishop’s palace at nearby Spynie.

Fragments of sculpture hint at Kinneddar’s monastic past

But my interest is in Kinneddar in the 9th and particularly the 10th century, and here the clues are few and far between. Despite its size and longevity, we know very little about its life as an early medieval monastery. It doesn’t appear in any written records until Bishop Richard took it on in 1187, so there’s no documented history to consult.

In fact, until the Northern Picts Project carried out excavations at the site in 2017, the best evidence for its importance was a collection of 32 fragments of carved stone found around the site in the 19th century, most of which are now on display in Elgin Museum.

(These are known, confusingly enough, as the Drainie stones, as Drainie is the name of the parish formed from the merger of Kinneddar and Ogstoun in 1669.)

A class I symbol stone - from the 7th century?

These carved fragments included one portion (now lost) of a Class I Pictish symbol stone, incised with a decorated crescent and v-rod; the most commonly-occurring of all the Pictish symbols. Class I stones are generally considered to date from the 7th century, and are sometimes considered to be culturally pre-Christian because of their lack of Christian symbolism.

The Northern Picts excavation in 2017 found that the first vallum ditch at Kinneddar was likely dug in the 7th century, so this symbol stone may have been contemporary with that activity. It may even have marked the entrance into the enclosure, as Class I stones do at sites like Rhynie in Strathbogie and Congash in Strathspey.

(UPDATE: Many thanks to Prof Katherine Forsyth, who has commented that the symbol stone was more likely to be 5th or 6th century, pre-dating the vallum - and perhaps an indicator that the monastery was built on an ancestral burial ground.)

But by the time it was re-found in 1855, it had long been cut down and used as building stone, so its original location and function on the site is unknown.

A Class II cross-slab with Pictish mirror and comb symbols

Also among the carved fragments was one portion of a Class II stone – a stone that combines both Pictish and Christian symbols, and which are thought to date from the 8th or 9th century.

These stones are typically dressed upright slabs, carved in relief on both sides, decorated with interlace and other patterns, and often featuring Biblical or allegorically Christian scenes. They’re closely associated with ecclesiastical sites and may have served as preaching aids to a Pictish-speaking congregation unable to read Latin (or indeed to read at all).

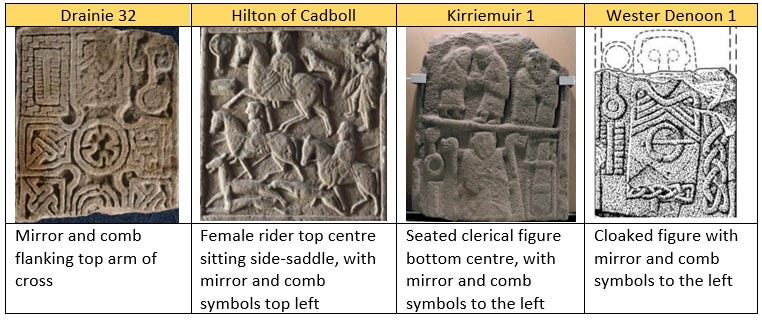

This particular stone, known as Drainie 32, is a fragment of a small cross-slab with symbols of a mirror and a comb flanking the cross. These common Pictish symbols are sometimes interpreted as designating a high-status woman, partly due to gender preconceptions and partly because the female rider on the Hilton of Cadboll stone seems to be ‘labelled’ with these symbols.

It’s worth noting, though, that two other Class II stones use the mirror and comb to ‘label’ figures who are not obviously female: a seated clerical figure on the back of the Kirriemuir 1 cross-slab, and a figure wearing a cloak and huge annular brooch on a cross-slab from Wester Denoon.

(UPDATE: Thanks again to Katherine Forsyth for commenting that both the Kirriemuir and Wester Denoon figures are most likely women - the Kirriemuir figure is seated next to a loom, and the Wester Denoon figure is wearing the brooch centrally rather than on the shoulder.)

While it’s clear that these symbols can be associated with individuals – and perhaps helped a contemporary audience to identify the individual meant – it’s not clear what they might have symbolised on a stone like Drainie 32.

Class III cross-slabs, free-standing crosses and box-shrines

The remaining 31 fragments from Kinneddar fall into Class III, a somewhat catch-all category that applies to any early medieval carved stone from the formerly Pictish-speaking regions of Scotland that bears Christian imagery but no Pictish symbols. In the case of Kinneddar, these fragments have been identified as parts of smashed-up cross-slabs, freestanding crosses and composite box shrines.

While cross-slabs are common across Pictland, freestanding crosses (stones carved into the shape of a cross) are quite unusual, and may point to Kinneddar having been a very important monastic site. Freestanding crosses abound on Iona, the head monastery of the Columban church, and are also associated with the Pictish royal site at Forteviot in Perthshire, where the freestanding Dupplin Cross is inscribed with the name of Castantin son of Uurguist, a Pictish king who reigned from 789-820 AD.

If freestanding crosses are unusual, then composite box-shrines are even more so. These were carved stone shrines to hold relics of saints – whether corporeal (their skull and/or bones) or incorporeal (things they had worn, touched or used). Saints could have been monastery founders like Columba, or Christian kings like Causantín mac Cinaeda, a 9th century king of the Picts who may once have been interred in the carved stone sarcophagus found at Govan near Glasgow.

Fragments of a similar box-shrine have also been found at nearby Burghead, the biggest promontory fort in Pictland, which suggests that relics may have been held at both places.

Overall, the carving of the Kinneddar fragments is noted to be of very high quality, and stylistically similar to carvings found at Rosemarkie, Burghead and St Andrews. In particular, a fragment from Kinneddar that shows a pair of hands wrenching apart a lion’s jaws is almost identical to a carving on the St Andrews sarcophagus – down to the draped sleeve folds and the prominent ribs of the lion.

Art historians associate this motif with the biblical king David, and suggest that its appearance in Pictish art signals a royal connection. The king most often cited for the St Andrews sarcophagus is Onuist son of Uurguist, an expansionist king who ruled from 732-761, in which time he conquered the kingdom of Dál Riata (modern Argyll) and may have founded the first monastery at St Andrews.

If Onuist’s relics were held in the sarcophagus at St Andrews, did some of them also travel north, to be held at the monastery of Kinneddar in the northern part of Onuist’s kingdom? Or does the Kinneddar David signal a connection with a different king?

Either way, these two great ecclesiastical centres were likely connected. Last year I attended an online conference celebrating the 1,500th anniversary of the birth of Columba. I asked the panel of one session if they had any thoughts on the relationship between Kinneddar and Iona, given that the 2019 Northern Picts dig showed Kinneddar to be a site of the same size and general plan as Iona.

Dr Adrián Maldonado was good enough to give me a detailed answer (for which I was very grateful as I was basically crashing an academic conference), saying that the sculptural links with St Andrews and Rosemarkie, along with the David imagery, suggest that Kinneddar was “an important place… one of a network of royally-sponsored monasteries along the North Sea coast of Pictland.”

What’s in a place-name? Decoding ceann-foithir

Another thing about Kinneddar may signal its high status in early medieval times. The name itself is from Gaelic ceann-foithir, and that second element, foithir, crops up suspiciously often in the names of places associated with early medieval royalty.

I recently wrote about two 10th-century kings of Alba who were (probably) killed at Dunnottar and Fetteresso. Both of those place-names contain the element foithir, as does Fettercairn, where another 10th-century king, Cináed mac Maíl Coluim, was killed in 995. In 834, the first Gaelic-speaking king of Pictland, Cináed mac Alpin, died in his royal palace at Forteviot, or foithir-tabhaicht.

Place-name scholar Dr Simon Taylor notes that foithir forms part of the names of many places that later became medieval parishes, which, as well as Kinneddar, Dunnottar, Fetteresso, Fettercairn and Forteviot, also include Fetterangus, Fetternear, Fodderty and Ferness (which I wrote about here).

So what does this word foithir mean? In Gaelic, it describes a landscape feature; a sort of terraced slope. But it seems to crop up too often in high-status places for this to be its only meaning. In The Place-Names of Fife vol. 5, Simon Taylor and Gilbert Márkus suggest it might come from a different root:

Given the fact that all these examples are in former Pictland, and that so many of them are of high-status places, it is possible that we are dealing with a [Gaelic] adaptation of a Pictish *uotir ‘territory’, perhaps some kind of administrative unit.

Taylor didn’t want to commit any further until a proper survey of these names has been carried out. But if it is a Pictish word meaning some kind of administrative unit, then Kinneddar, ceann-foithir, was the ‘head’ or ‘end’ of one such unit.

The University of Aberdeen’s Northern Picts team suggest that if Kinneddar was at one ‘end’ of an ‘administrative unit’, the unit in question could have been the ridge of Duffus, which stretches westwards from Lossiemouth to Burghead.

In the first millennium AD, this ridge would have been almost an island, flanked by the Moray Firth on its north side and two shallow sea lochs, Loch Spynie and the Loch of Roseisle (which I wrote about here), to the south.

The Northern Picts’ Kinneddar excavation report says:

Kinneddar may have been either a centre or more likely a subordinate focus to an administrative unit in the area. Given the area’s geography, largely cut off from the mainland, it is likely that Burghead was a significant part of the same entity, probably the territory’s centre.

Burghead and Kinneddar do seem to have been almost exactly contemporary sites, with carbon dating from digs there putting the start date of the great fort at Burghead at 570-630 and the start date of Kinneddar at 585-655. Both were also very long-lived, with Burghead being destroyed by burning between 930 and 980, and Kinneddar continuing as a site into the early modern period.

If you know the area, it’s quite something to imagine these two enormous and seemingly royally-connected sites occupying either end of an “island” rising above inland lochs and marshes.

Today, Kinneddar sits on a rather featureless stretch of the Laich of Moray, an arable plain created through drainage from the 12th century onwards. But in its time, it would have sat at the shore of Loch Spynie, with a harbour and jetties for receiving visitors and unloading the imported goods required for Christian worship: wine and olive oil, and perhaps exotic materials like the gold wire that wrapped the 9th century rock crystal jar found in the Galloway Hoard.

Is there any link between Kinneddar and Sueno’s Stone?

I’ve learned a lot about Kinneddar in the research for this post, but I’m not sure how much of it I can relate to Sueno’s Stone.

One thing I find intriguing about Sueno’s Stone is that it was clearly a major project: at the very least, this huge 7m slab of stone had to be quarried, transported to the carving workshop, dressed, carved, transported to its site near Forres and erected there.

To me that implies the availability of these kinds of skills in the vicinity – especially as Sueno’s Stone must have been an unusually challenging project, given its size. I thought I might find these skills at Kinneddar, which clearly had a sophisticated sculpture workshop and is located close to the sandstone quarries on the Duffus ridge.

But the dates don’t quite add up: the heyday of the sculpture workshop at Kinneddar seems to have been in the 8th and perhaps early 9th centuries, whereas the date art historians give for Sueno’s Stone is 850-950 (and Archie Duncan put it even later, after 966). No other richly carved ‘Pictish’ stone has been given this late a date range, and it seems generally that richly sculptured stones had gone out of fashion by this time.

So if Sueno’s Stone wasn’t carved at the monastery of Kinneddar, where was it carved, and to whose brief? All this still to come as I continue to dig around in 10th-century Moray…

References

J.R. Allen and J. Anderson, The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland (1903)

D. Clarke, A. Blackwell and M. Goldberg, Early Medieval Scotland: Individuals, Communities and Ideas (2012)

T. Clarkson, The St Andrews Sarcophagus

S. Driscoll, Alba: The Gaelic Kingdom of Scotland AD 800-1124 (2002)

A.A.M. Duncan, The Kingdom of the Scots in The Making of Britain: The Dark Ages (1984)

I. Henderson and G. Henderson, The Art of the Picts (2004)

N. McGuigan, Máel Coluim III ‘Canmore’: An Eleventh Century Scottish King (2021)

National Museum of Scotland, The Galloway Hoard Rock Crystal Jar (blog post)

G. Noble et al, Kinneddar: A Major Ecclesiastical Centre of the Picts (2019)

R. Oram, Domination and Lordship: Scotland 1070-1230 (2011)

R. Oram, Moray & Badenoch: A Historical Guide (2001)

J. Stuart, The Sculptured Stones of Scotland (1856)

S. Taylor and G. Márkus, The Place-Names of Fife vol. 5 (2013)

C. Thomas, The Early Christian Archaeology of North Britain (1971)

Hi Fiona. Too much in this blog to comment on, so just one thing … You keep saying that ‘art-historians’ have given a date 850-950 for Sueno’s stone. Not really true, just one art-historian, and lots of other researchers and archaeologists who have disagreed and placed it much earlier, mid 700s likely. In which case your sound idea that we could expect it to come from the significant Pictish stone-carving group at Kineddar, especially as the stone is sourced nearby, fits neatly with this current dating. This reminds me of once as a wee young thing, staring down a microscope trying to draw the insect under it, and the ancient and beloved professor peered over my shoulder and said: You’ll be a good scientist one day – if you see what you’re seeing, not what you think you should be seeing!

A v minor point but loom to right of seated figure on Kirriemuir 1 presumably indicates she is female (looks female to me!), also central position of brooch (rather than shoulder) at Wester Denoon, also suggests female (I'm sure there's an article in an old PAS Journal on this). Also, I think the Kineddar Symbol stone more likely to be 5th or 6th century than 7th, so predating vallum (church founded on site of ancestral burial ground? - a common pattern). As ever, enjoyed having my attention directed to this area - so much of interest!