Sueno's Stone and the death of king Dubh of Alba

Does a leading theory about Sueno's Stone stand up to scrutiny?

If you’re following this blog, you’ll know that in my MA dissertation I plan to examine the theory that Sueno’s Stone in Forres commemorates the death (or murder) of king Dubh of Alba in 966 AD.

This theory was first put forward by Professor A. A. M. (Archie) Duncan in a 1984 book produced by Channel 4 and London Weekend Television to accompany the TV series The Making of Britain. He later repeated it in his 2002 book The Kingship of the Scots: Succession and Independence 842-1292.

Given Professor Duncan’s eminence as a historian of medieval Scotland, the idea that the stone commemorates the death of Dubh has gained widespread acceptance – at least as a possibility.

It appears on Historic Environment Scotland’s information board at Sueno’s Stone as one of three possible interpretations of the events depicted on the stone:

The relevant part reads:

The third possibility is that the stone relates to a conflict fought at Forres in 966 during which the Scottish king, Dubh, was killed by the men of Moray. After the battle the dead king’s body apparently lay beneath the bridge at Kinloss, a short distance away. Is the curious arched object near the bottom of the battle scene this bridge? And is the specially framed head from one of the decapitated bodies that of King Dubh? The absence of an inscription on the stone forbids a firm conclusion.

So far, so many questions. But where did this theory come from in the first place?

Dispatches from 10th century Scotland

Answering that means diving into the murky waters of the medieval sources – the earliest surviving manuscripts that deal with events in 10th century Scotland.

In one group of these texts, sometimes called the Chronicle of the Kings of Scotland, 1 the reign and demise of Dubh is related more or less as follows:

“Dub, Malcolm’s son, reigned for four years and six months; and he was killed in Forres, and hidden away under the bridge of Kinloss. But the sun did not appear so long as he was concealed there; and he was found, and buried in the island of Iona.”

A different source, confusingly called the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba (CKA), relates a battle during Dubh’s reign between Dubh and his cousin (and king in waiting) Culen:

“[A battle was fought] between Dub and Culen, upon the ridge of Crup, and in it Dub had victory. And there fell Duncan, abbot of Dunkeld, and Dubdon, lord of Athole. Dub was driven from the kingdom.”

In 1984, Prof Duncan wove these two disparate records together to come up with this theory:

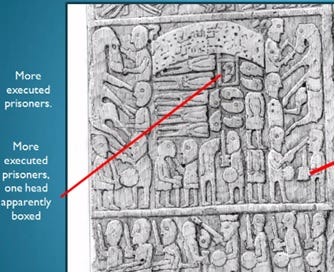

“By the road out of Forres to Kinloss there stands a remarkable monument, now badly eroded, with the irrelevant name Sueno’s Stone. On one side, carvings depict a great army on horseback. Below, a central figure with a helmet and quilted coat (Dubh, I suggest) watches with his armed retinue while the armies begin to fight on foot […] The battle continues with three fighting couples on each side of an arc which is the bridge of Kinloss. Beneath the bridge lie more bodies and severed heads; one of the heads, that of Dubh, is framed to stress its importance.”

Here’s how that last bit (in bold) looks, as drawn by John Borland:

In essence, then, Duncan is suggesting that:

Dubh was killed in the battle with Culen that took place on the ridge of Crup

During the battle, his body (and head) were placed under the bridge of Kinloss

Sueno’s Stone is a monument to Dubh that commemorates these events

So how well do these suggestions stack up?

Did Dubh die in battle on the ridge of Crup?

The first thing to note is that this theory assumes that the battle “on the ridge of Crup” took place near enough to Kinloss for the battle-dead to be collected underneath a bridge there.

Unhelpfully, nobody knows where the “ridge of Crup” (“dorsum Crup” in the original Latin) actually was.

You could argue that Forres sits on a low ridge above the Moray Firth, but as far as I know, there are no place-names like “Crup” in the area. According to Dr Alex Woolf in From Pictland to Alba 789-1070, the site was likely Duncrub in Perthshire, or perhaps Cruban Mor/Cruban Beg in Badenoch.2

In any case, did Dubh actually die in this battle? According to CKA, “Dub had the victory” and was later “driven from the kingdom”. So he appears to have left the battlefield very much alive – not piled in pieces under a bridge.

The fact that Dubh survived the battle is in fact confirmed by the Annals of Ulster, a reliable contemporary source from Ireland. It records the battle in its roundup of political affairs for 965:

965.4: A battle between the men of Scotland themselves, and there many were slain, including Duncan, the abbot of Dunkeld.

If Dubh had died, he would have had top billing above the abbot of Dunkeld. But he isn’t mentioned at all, and in fact the Annals of Ulster record his death the following year, at the hands of his fellow-countrymen:

967.1: Dub son of Mael Coluim, king of Scotland, was killed by the Scots themselves.3

This alone casts doubt on Prof Duncan’s reading of Sueno’s Stone. Dubh didn’t die in the battle against Culen on the ridge of Crup, which probably wasn’t anywhere near Forres in any case. In fact there’s nothing in the contemporary Irish annals to suggest Dubh died in battle at all. All we know from that source is that he was killed by his fellow-countrymen, with no indication of where or how.

What of Forres and the bridge at Kinloss?

So what are we to make of the tales about the murder at Forres, the concealment of the body under the bridge at Kinloss, and the sun failing to shine while the body lay hidden?

Those details only appear in later manuscript sources, written down long after Dubh was safely interred on Iona (if he even was). But when were they written, where did these details come from, and how reliable are they?

This is where things get very tricky for the student of early medieval Scotland. There are no annals or other types of documentary record from 10th-century Scotland itself. Scotland has no equivalent of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, or even the Annals of Ulster. If such texts ever existed (and they may well have done), they are long gone.

Any details we think we know about the kings of Alba in the 10th century come instead from a scattered collection of later manuscripts that appear to draw on earlier, long-lost sources.

It’s a very daunting world to pile into, and it’s probably foolish to even try to do it on my own without some kind of academic supervision. But luckily I do have a lot of help in the form of these two excellent books:

Early Sources of Scottish History collects together all the records for any given year (regardless of their reliability) and provides English translations of them, while Kings and Kingship in Early Scotland tries to trace the relationships between different sources and their dates of production. It also presents all the texts in their original Latin (or French, in one case).

As I don’t have access to the manuscripts themselves, it’s in these two books that I need to dig about to work out when the story about Dubh’s murder in Forres and concealment under the bridge at Kinloss entered the record, where it came from, and how much faith we should put in it.

I’m not at that point yet, so that will be a blog for another time. But there’s one detail that does seem to stack up. Most of these tales make much of the fact that “the sun did not appear” while Dubh’s body lay hidden under the bridge. Alex Woolf notes that there was a solar eclipse on 20th July 966, the year Dubh died. Does that lend credence to the rest of it? That’s what I need to figure out.

References

Annals of Ulster, online at https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T100001A/

A. O. Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History A.D. 500 to A.D. 1286 (1922)

M. O. Anderson, Kings and Kingship in Early Scotland (1973)

A. A. M. Duncan, The Kingdom of the Scots, in The Making of Britain: The Dark Ages (1984)

A. A. M. Duncan, The Kingship of the Scots, Succession and Independence 842-1292 (2002)

Alex Woolf, From Pictland to Alba 789-1070 (2007)

In my last blog, I said this is from the manuscript known as the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba. In fact it comes from a different group of manuscripts, known as the Chronicle of the Kings of Scotland. Even navigating the names given to these texts, let alone their actual content, is tricky! (I may not even have got it right yet…)

Fans of Roman Britain may be intrigued to know that, according to Alex Woolf, the ‘ridge of Crup’ may be the same name, and the same place, as Mons Graupius, the similarly-named site of a famous battle between Agricola and the Caledones in 83 AD.

AU has the year as 967, but it was in fact 966 as the dating in AU is slightly out.

Hi Fiona. Going back to the text of CKA in Skene I see that the Latin term used for the bridge, perhaps unsurprisingly, is ponte. But then looking at the translation from Medieval Latin on http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=ponte&la=la#lexicon this gives a description of the bridge as "a board across a ditch, brook, etc". Doesn't help with the curved shape on Sueno's Stone though