The Princess Stone and the place-names of the Findhorn valley

In which I jump to foolish conclusions as I hunt for an early medieval church site

The trouble with studying early medieval Scotland is that, because contemporary sources of information are almost non-existent, it’s very easy to fall into the trap of antiquarian speculation.

You think you’ve spotted a pattern – one that nobody else has spotted – and the next thing you know, you’re setting up a crazy wall and merrily connecting random things with bits of red wool as you convince yourself you’ve solved a mystery that’s been bothering historians for decades.

I’ve read enough scholarly monographs and academic papers to know this isn’t the way to do history. And yet this week, to my shame, that person with the red wool and the mad glint in their eye was me.

It started with a map…

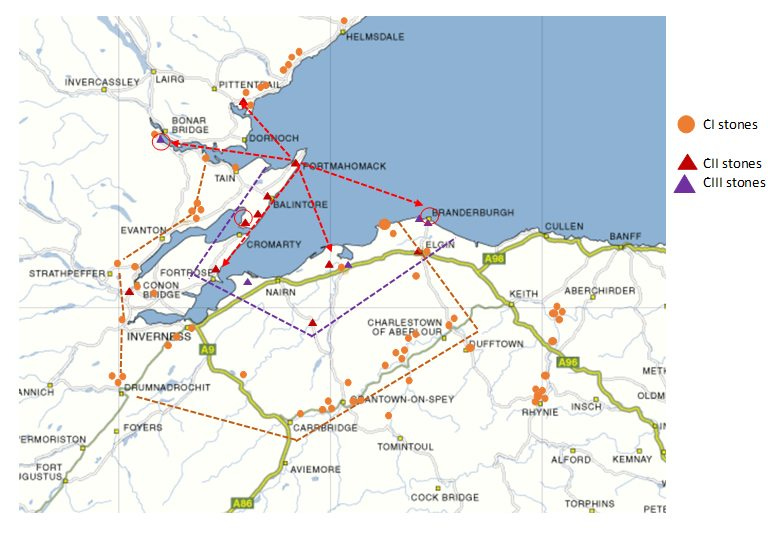

It all started with a post in the Pictish Symbols: Art and Context Facebook group. Group admin Helen McKay posted a map showing the distribution of Pictish stones in the inner Moray Firth area:

(NB Class II stones are dressed stones carved in relief with Christian and Pictish symbols, while Class I stones tend to be unshaped boulders incised with Pictish symbols only. Class III stones only have Christian symbols, usually a cross.)

Something struck me about the Class II distribution. All of the Class II stones in this area are located on the Moray Firth coast or in its flat, fertile hinterland – except one. The so-called “Princess Stone” sits higher up in the Findhorn valley, on a bluff above the river in the grounds of Glenferness House.

The Princess Stone is an unusual stone in another way too. It bears two pairs of Pictish symbols, rather than the usual single pair. Opinion on Facebook was that it might mark a boundary between two early medieval population groups, one indicated by the first pair of symbols (a Pictish beast and a crescent and V-rod) and the other by the second (a double disc and z-rod and another Pictish beast).

![19th-century sketches of the two main faces of the Princess Stone, a class II Pictish symbol stone. A. Mack's Field Guide to the Pictish Symbol Stones reads: "[Below] the cross are figures. On the reverse the lower of two panels holds an elephant over a crescent and V-rod below which are a double disc and Z-rod and another elephant.To the left of the upper symbols are the figure of a hooded crossbowman and of a hound." 19th-century sketches of the two main faces of the Princess Stone, a class II Pictish symbol stone. A. Mack's Field Guide to the Pictish Symbol Stones reads: "[Below] the cross are figures. On the reverse the lower of two panels holds an elephant over a crescent and V-rod below which are a double disc and Z-rod and another elephant.To the left of the upper symbols are the figure of a hooded crossbowman and of a hound."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!3PjQ!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5fa623c1-57c7-4dd1-b728-e9ade03e2331_456x500.jpeg)

I’ve vowed to stay out of the Pictish symbols debate, so I didn’t have anything to suggest on that front. But it didn’t stop me wondering about the context of the Princess Stone. Why is it located up here in the Findhorn valley? Nothing was found underneath it when it was moved to higher ground in the 19th century, so it seems likely it wasn’t a grave marker. Did it mark an early church site?

Logie, Dalnaheiglish – significant place-names?

This is where my imagination started to run away with me. I have a terrible weakness for obsessing over maps and place-names, and on firing up OS Maps, I immediately noticed some names in the vicinity of the stone that looked interesting.

For a start, a little way downriver of the stone is a wood called “Dalnaheiglish”, which means “meadow of the church” in Gaelic. I’ll come back to that one in a bit.

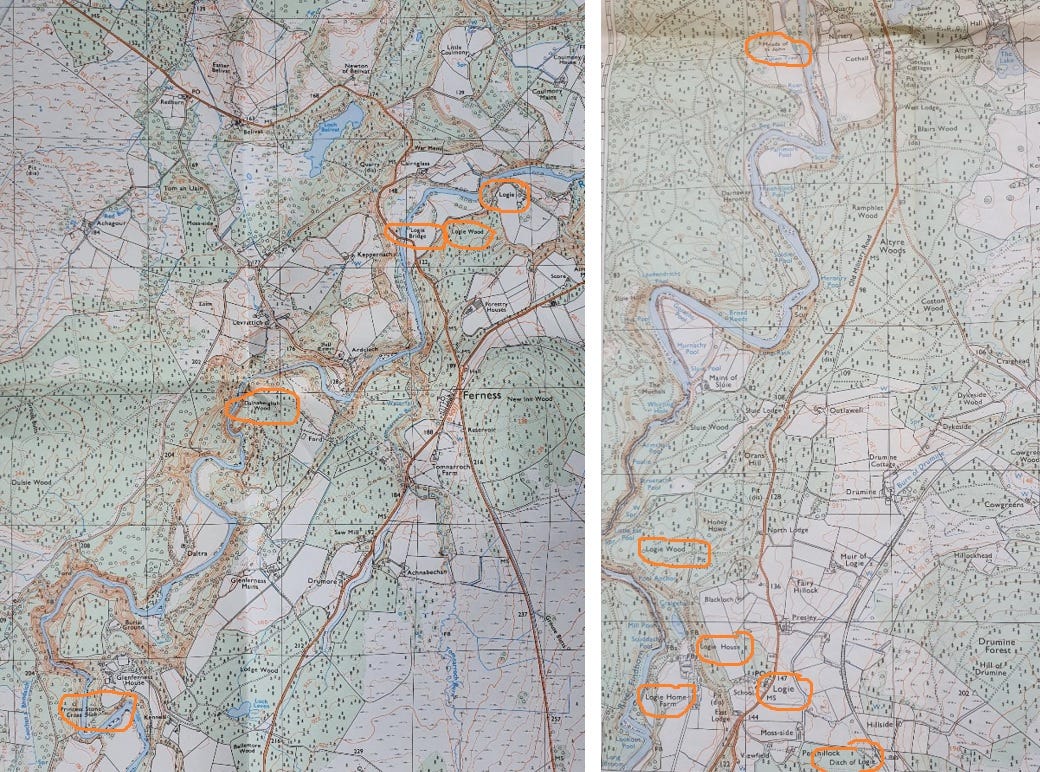

Then there’s the fact that the lower Findhorn valley is littered with names that include the element “logie”. Travelling northwards downriver from Dalnaheiglish you pass Logie Wood, Logie Bridge and Logie, then a few miles later, Moss of Logie, Logie House, another Logie Wood, and Muir of Logie.

The southerly names cluster around what looks to be a farmhouse (see left-hand map below), while the northerly set form the Logie Estate (see right-hand map below).

Two types of Logie- name

So what, you might think. But I’m particularly excited by “logie” place-names, thanks to a 2016 paper by Celtic linguist Professor Thomas Owen Clancy of the University of Glasgow.

Called Logie: An Ecclesiastical Place-Name Element in Eastern Scotland, it starts:

“Logie is a fairly common place-name and place-name element in Scotland east of the Great Glen, north of the Forth and south of the Dornoch Firth. Previously, it has been taken that it derives from Scottish Gaelic (ScG) lag ‘a hollow’, earlier log, developing from Old Irish/Old Gaelic (hereafter OG) loc ‘hollow, ditch’.”

Clancy goes on to explain that this generally-accepted etymology doesn’t fully explain some of the Logie place-names in northern and eastern Scotland (i.e. Pictland of old):

“There are some peculiarities to the cohort of logie-names; for instance, there are a large number of churches ‒ mostly parishes ‒ employing this element and, where we have historical forms of these, they first appear as login or logyn, so they cannot derive from an earlier logach/lagach or its dative logaidh/lagaidh.”

Spoiler: Clancy goes on to argue that many instances of Logie derive not from Gaelic lag but from Latin locus, or (holy) place ‒ and may be Pictish in origin rather than Gaelic. In their earliest historical forms, they’re often suffixed with the name of a saint, and may therefore indicate the site of an early church dedicated to that saint.

He identifies the northern cluster of Logie names in the Findhorn valley as one such, noting that in 1208 x 1215, it appears in the records as Logyn-Fithenach, and may be linked with local place-names that evoke John the Baptist, such as Ihons-logy from Pont’s 1590 map of Nairnshire (see below), Meads of St John and St John’s Pool.

All of this suggests there should be a medieval church site somewhere around the Logie estate, but Clancy admits its actual whereabouts is a mystery:

“It has been difficult to establish exactly where the medieval church lay. […] Presumably [it] lay near the Meads of St John, on the east of the Findhorn.”

(Incidentally, if you scroll back up to the OS maps in the last section, you’ll see the Meads of St John circled in orange at the top of the right-hand map. They aren’t very close to Logie, which makes me think Clancy may be stretching things a bit here. But I’m still convinced by the overall idea that some Logie names are ecclesiastical in nature.)

As interesting as all this is, it’s too far north to be a church associated with the Princess Stone. But what about the other cluster of Logie names, further upriver? Disappointingly, Clancy has nothing to say about this one, so I reluctantly conclude that this is a case of lag (hollow) rather than locus (church).

What about Dalnaheiglish, though?

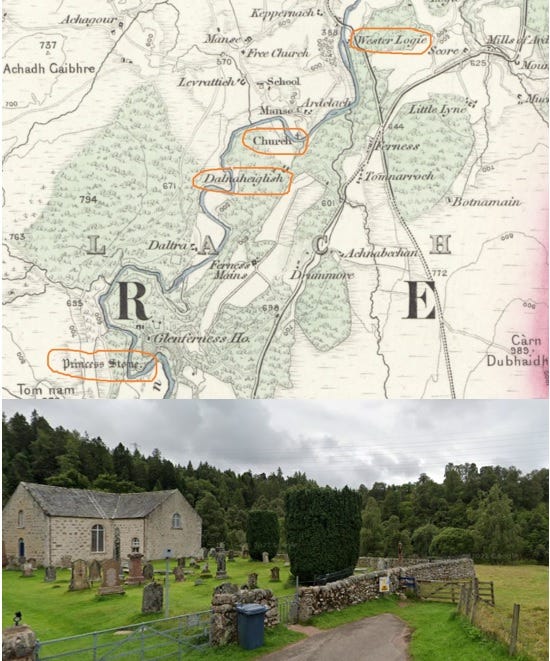

But this is by no means the end of the line for my amateur investigation. There’s still Dalnaheiglish (“meadow of the church”) to think about. This one is pretty close to the Princess Stone ‒ see 1876 OS map below ‒ so could it be the location of the original Pictish-era church?

A couple of things militate against that. Firstly, eaglais is still in use today as the Gaelic word for church, so an eaglais place-name doesn’t necessarily imply any great antiquity. Secondly, Dalnaheiglish sits squarely opposite Ardclach church on the other side of the river. Perhaps it was the meadow belonging to that church, or – more likely – the meadow from which that church could be seen?

Even so, I Google Dalnaheiglish to see if anyone has given this place-name any thought from an archaeological point of view. To my delight, up comes a Historic Environment Record hinting at another lost medieval chapel:

“No traces are visible of a pre-Reformation chapel recorded at Ferness (village centred NH 962 449) and possibly associated with St Luag. (Dalnaheiglish - name at NH 952 446 on OS 6" map, Nairnshire, 1st ed., (1874), sheet viii - means 'meadow of the church'.) – NSA 1845; H Scott et al 1915-61; RCAHMS 1978, visited May 1978”

It looks like I am on to something! Not only was a medieval chapel recorded at nearby Ferness, but it may have had a dedication to St Moluag, a sixth-century saint who founded a monastery on the island of Lismore, and who is culted at quite a few places in north-east Scotland.

Reader, this is where I commit a terrible error. The Wikipedia entry for Moluag gives a number of alternative spellings of his name: Lua, Luan, Luanus, Lugaidh, Moloag, Molluog, Molua, Murlach, Malew. My eye alights on the spelling Lugaidh and my synapses start firing. Is this the root of the northern cluster of Logie names?

I get out the metaphorical red wool and post-its and start connecting things. The Princess Stone, the meadow of the church, Logie/Lugaidh… could all these things hint at a cult site on the east bank of the Findhorn dedicated to this Pictish-era saint?

I learn the error of my ways

Excited, I return to the Facebook group to float this hypothesis – whereupon I am immediately and rightly slapped down for my utter ignorance of Gaelic. Lugaidh doesn’t have a hard ‘g’ – as should have been immediately obvious to me from all the other spellings. So it couldn’t have given rise to a place-name that has a hard ‘g’ – not to mention one whose meanings are already well established.

(What’s more, the excellent Saints in Scottish Place-Names database has no record of a Moluag name in the Findhorn valley. The nearest one is at Cromdale in Strathspey.)

I’d fallen into the trap of wanting everything I was looking at to be related: of thinking I was following a trail of clues that would lead to a treasure – in this case, the site of a lost early medieval church associated with the Princess Stone.

Instead, what I’d really found was fool’s gold: a place-name that probably means “low-lying place”, a meadow that overlooks a church, and insinuations of a couple of lost chapels that don’t lead anywhere substantial. A reminder that 1,000+ years of human endeavour produce complex, multi-layered name-scapes that are difficult to read, even by experts. Not a trail of simplistic clues for a noob like me to follow!

More to discover in the Findhorn valley?

(WARNING: This last bit contains massive unevidenced assumptions which are just broad brushstrokes of things I’m thinking about as I gear up for my MA…)

All the same, I don’t think this is the last of my efforts to attempt to ‘read’ the Findhorn valley from an early medieval perspective.

If you’re a fan of Alex Woolf (or if you are Alex Woolf; I can dream that he might read this blog) you’ll know that a key piece of evidence he submits for a northern location for the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu is this entry from the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba:

“Causantín mac Aeda held the kingdom forty years. In his third year the Northmen plundered Dunkeld and all Albania. The very next year the Northmen were slain in Sraith Herenn.”

Until 2006, historians believed the “Sraith Herenn” where this battle took place in 904 AD was Strathearn in Perthshire. However, Woolf pointed out that the original name of the Findhorn was also the Earn (see a grant of “unum rete in aqua de Eren” from David I to Kinloss Abbey), and so Sraith Herenn might equally be the Findhorn valley.

If we accept a northern location for Fortriu, its royal centre might well have been the huge Pictish fort at Burghead, which may been superseded after its destruction by a royal site at Forres, where three tenth-century kings of Alba are said to have died.

If the Findhorn valley was a main artery to and from Forres in the first millennium, we might expect at least one wayside church where southbound travellers could pray for a safe journey through the desolate Highlands ahead, and northbound travellers could give thanks for a safe passage.

Might we even consider a victory church in the valley, commemorating Constantin’s defeat of the Northmen in Sraith Herenn in 904? That one might be a bit harder to evidence! But I’m certain there’s a lot more to uncover - and next time I’ll forgo the red wool and post-its and attempt some proper research.

References

J. Anderson and J.R. Allen, Early Christian Monuments of Scotland (1903)

T.O. Clancy, Logie: An Ecclesiastical Place-Name in Eastern Scotland (2016)

A. Mack, Field guide to the Pictish symbol stones (2007)

Ordnance Survey Pathfinder 1:25,000 map, Forres and Dallas (1981)

Ordnance Survey Pathfinder 1:25,000 map, Cawdor and Ferness (1995)

Ordnance Survey one inch to the mile map, Sheet 84, Nairn (1876)

People of Medieval Scotland (POMS) Database

T. Pont, Map 8, Moray and Nairn (1590)

Saints in Scottish Place-Names Database

J. Stuart, Sculptured Stones of Scotland (1856)

A. Woolf, Dún Nechtain, Fortriu, and the Geography of the Picts (2006)

A. Woolf, The Cult of Moluag, The See of Mortlach and Church Organisation in the North of Scotland in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (2007)

I did a quick bit of digging into Cothall / Loggie (my primary interest is in castles) and while doing so came across a few references to your church. You may have seen these already but I thought I would share them in case you hadn't.

Oliver O’Grady’s PhD mentions the chapel:

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/506/

As does the POWiS site:

http://www.scottishchurches.org.uk/sites/site/id/4049/name/St+John%27s+Chapel+Site%2C+Rafford+Rafford+Grampian

Both referring to the entry in the OS Name Book for Morayshire:

https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/digital-volumes/ordnance-survey-name-books/morayshire-os-name-books-1868-1871/morayshire-volume-23/14

The relevant Canmore entry:

https://canmore.org.uk/site/15786/st-johns-mead

There's also an extensive investigation into the church by Thomas Owen Clancy in The Journal of Scottish Name Studies, Volume 10:

https://clog.glasgow.ac.uk/ojs/index.php/JSNS/article/view/133

Just to reinforce your lag / log conclusion, Logie House certainly sits in something of a hollow in the wider landscape.