The sword and the stone: Evidence of early medieval kingship rituals in Forres?

In which I ponder the significance of some intriguing marks carved into Sueno’s Stone

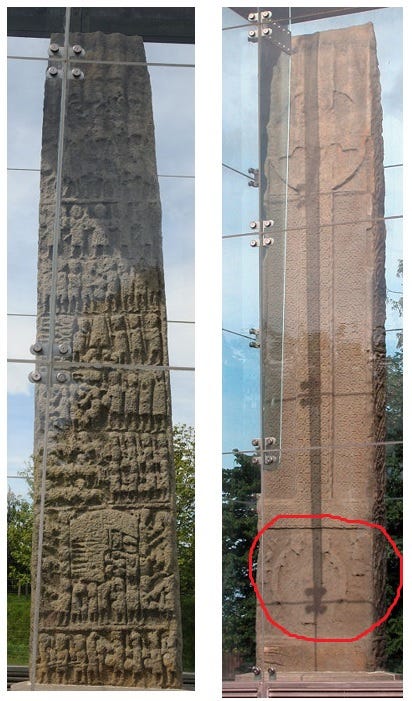

For this blog I’m returning to Sueno’s Stone near Forres, to look at one of the most perplexing of all of its carved scenes—and, more specifically, at a curious feature that appears below it.

On the cross side of the stone, immediately below the towering five-metre tall cross, is a panel that has puzzled antiquarians and historians just as much as the more famous battle scenes on the reverse.

The panel (circled in red below) appears to show two figures bending over a central figure. This figure has been so heavily eroded—or actively defaced—that only the lower part of a tunic and two legs remain visible. To either side, a pair of smaller figures seem to be attending the scene, apparently bearing objects.

I’m far from ready to provide any kind of interpretation of my own for this scene, or for its apparent defacement. But perhaps I don’t have to. A highly plausible interpretation was put forward in 1979 by the legal historian (and later Lord Lyon King of Arms), the late David Sellar.

Sellar was the first to note the strong similarities between (what’s left of) the scene and an iconic image of early Scottish kingship:

[The] scene on the panel, indistinct though it is, bears a striking resemblance to that on the common seal of the Abbey of Scone, thought to represent the inauguration of the medieval kings of Scots. Could the panel represent the ceremonial inauguration of the king of Scots after the final defeat of the Pictish monarchy?

Plausible as it is, this interpretation raises a lot of questions. Sueno’s Stone is generally thought to have been erected between 850 and 950 AD—indeed the exact time that the Pictish kingship gave way to a new Gaelic-speaking dynasty starting with Cináed mac Alpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) c. 843 AD.

But the kings that we know about in this period were based around Perth, not Forres. The tenth-century Chronicle of the Kings of Alba tells us (for example) that in 858 AD Cináed mac Alpin died in his palacio at Forteviot, that his brother Domnall died in 862 AD in a ráth (fort) at Inveralmond, and that in 906 AD a joint proclamation was made at Scone by Causantín mac Áeda and bishop Cellach.

Forres is nowhere near any of these places. In fact it’s never mentioned at all in the earliest written sources of Scottish history. If it was a royal inauguration site, it has gone completely unrecorded. So what are we to make of this carved scene: one that’s entirely unique in Scotland’s early medieval sculpture? Were kings anointed here – and if so, who were they, and what were they kings of?

An intriguing new observation made in 2020

Part of the answer may lie in a curious feature of the stone that seems to have been completely overlooked until 2020, when University of Aberdeen postgraduate student Ruth Loggie drew attention to it in her Archaeology MSc dissertation, titled A Revisit to Sueno’s Stone. In it, she wrote:

Underneath the anointing scene are lines of sword blade groove marks, beside which there is a probable burnished surface.

Indeed, these ‘sword blade groove marks’ and accompanying ‘burnished surface’ are clearly visible in a detail from a recent drawing of the stone by ex-Historic Environment Scotland measured survey manager John Borland (below). What’s more, they appear in a kind of framed panel near the base of the stone that almost seems to have been designed for some specific purpose.

If this were a Roman monument, it’s the sort of place we might expect to find an inscription, like the one below from the tombstone of Regina found at the fort of Arbeia (South Shields) on Hadrian’s Wall. But rather than an inscription, this panel on Sueno’s Stone features a series of nine horizontal cuts or grooves, appearing on the left-hand side only, leaving the right-hand side seemingly blank.

Sueno’s Stone has so many other intriguing features that these grooves seem never to have merited a mention by any of the antiquarians, archaeologists and historians who have studied the stone.1 But when Ruth Loggie saw them on John Borland’s drawing of the stone, her interest was piqued.

She told me via email that Dr James O’Driscoll, a research fellow in the Archaeology department at Aberdeen, then pointed her towards a 2009 paper by Conor Newman of the University of Galway, which examines the same phenomenon on early medieval carved stones in Ireland and Wales.

Irish parallels for the Sueno’s Stone sword-marks

Called The Sword in the Stone: previously unrecognised archaeological evidence of ceremonies in the late Iron Age and early medieval period, Newman’s paper is a fascinating re-assessment of the linear grooves on early medieval stones that are usually attributed to vandalism or knife-sharpening.

Newman shows quite convincingly that these are not random or unthinking acts of vandalism, but evidence of carefully-observed ritual: one in which the sacred nature of the cross-slab is used to ‘charge’ a bladed weapon with divine power.

The marks, Newman says, were produced by drawing a blade across the stone, usually in an undecorated portion close to the ground—just as they are on Sueno’s Stone.

The grooves […] are typically straight, narrow and v-sectioned. Sometimes deepening along the middle of the groove, they clearly result from repeated sawings of a narrow metal blade back and forth across the surface of the stone under considerable downward pressure.

Such an action, he argues, would not result in a sharpening of the blade but rather a blunting of it. In fact, he observes that these ‘sword-marks’ often occur beside a polished or burnished area of the stone that may actually have been used for the practical purpose of sharpening.

Evidence for early medieval stone-marking ritual

Interestingly, Newman produces evidence from medieval Irish literature that suggests this was an early medieval practice rather than a much later re-use of an existing stone. The earliest of his examples, dating from the late seventh or early eighth century, is the Baile Chuinn Chétchathaig, a list of early kings of Tara; holders of the Irish high-kingship.

Several lines in this text refer to the striking of blows in connection with the high-kingship. Newman enlists the help of Tara expert Dr Edel Bhreatnach, who believes they refer specifically to the striking of a stone with a sword—and not just any stone, but the Lia Fáil, the Stone of Destiny.

Given that the Lia Fáil legendarily emitted a sound when approached by a rightful claimant to the high-kingship, Newman concludes:

[The reference in the text to striking a blow] may be a metaphor for striking a blow on the Lia Fáil, and hence the screech that emanated from the Lia Fáil when recognising the legitimate heir to the kingship of Tara may be a metaphor for the sound of the grinding sword against the stone.

This is quite some context for the practice of marking a stone with a sword, and since there seem to be many stones across Ireland, Wales and Scotland that bear these sword-marks, it might be a bit of a stretch to attribute them all to rituals of high-kingship.

Boundary markers and treaty enactments

However, Newman also identifies other contexts in which a sacred stone appears to have been ritually marked with a sword. One example is the Kilnasaggart pillar stone in County Armagh, which, he points out, occupies an extremely significant location in the landscape:

[It] stands squarely in the middle of a narrow pass that is one of just a handful of gaps in the 65 million-year-old volcanic ring-dyke that surrounds Sliabh Gullion and forms the virtually impregnable southern border of Armagh.

This, then, is frontier territory, and anyone crossing the border couldn’t fail to pass the Kilnasaggart stone. To Newman, this suggests an additional explanation for the sword marks:

Whereas blade marks such as these are capable of emitting very clear signals of ownership and the force of arms, the importance of boundaries as places of assembly where laws and treaties were enacted and renewed suggests that the blade marks on the stone should be considered in this context as well.

How might Newman’s theories apply to Sueno’s Stone?

There is so much more in Newman’s paper, and I urge those interested to read it. But for this blog I wanted to think about whether either (or both) of these contexts—kingship ritual and treaty enactment at a significant boundary—could apply to Sueno’s Stone.

Loggie, for her part, believes both contexts apply. Combined with the inauguration scene and the battle-scenes on the reverse of the stone, in which she suggests one figure is wearing a crown, she believes the marks suggest a connection with élite power:

The depiction of leaders amongst the martial iconography of the stone and in particular the figure with a crown, alongside the sword marks, reinforces the case for the site having a ritual element and having elite status.

Her conclusion is that Sueno’s Stone can reasonably be interpreted as a royal inauguration site, despite the lack of written evidence:

The rites of kingship and inaugurations occurred in Scone, Perthshire, with Scone being an important royal place from 902 AD [recte 906 AD], however, there is no hint of other local places of inauguration from the ninth century onwards. The iconography and location of Sueno’s Stone strongly advocate that it could be put forward as one such example of an inauguration site and that it was an elite power centre.

Again taking her cue from Newman, Loggie further suggests that Sueno’s Stone once stood on an important boundary, and as such may also have served as an assembly place for the swearing of oaths and fealty, and witnessing of treaties:

The marks […] indicate the fact that the stone was no ordinary monument, but was, in fact, an icon of cultural identity and again, strengthen the case for marking a significant boundary… [They] can be interpreted as personal signatures bearing witness to those oaths or treaties and can even be construed as marks showing a commitment to peace or fealty.

For Loggie, then, the low ridge on which Sueno’s Stone stands was potentially a place where rulers were legitimised, where oaths and pledges of allegiance were sworn, and where peace treaties were enacted. And these acts were literally set in stone by the use of a sword to make a permanent mark, equivalent to a seal or signature.

A compelling theory with many unanswered questions

At face value, I find this argument pretty compelling. By virtue of its massive size, complex iconography and position at a junction of two routeways, beneath an enormous Iron Age hillfort, looking out to the Moray Firth and close to a high-status Pictish burial site of fifth to seventh-century date, Sueno’s Stone clearly served an important purpose in its time.

But dig any deeper, and questions start to mount up. If kings were inaugurated here, which kings were they, and why have we never heard of them? If the stone marked an important boundary, which territories was it on the boundary of? If peace treaties were signed here, who were the opposing factions? Whose swords gouged the grooves into the stone, and when?

These aren’t questions I can definitively answer, but I think I can make some suggestions.

The first is that, as far as I know (and that’s only from reading Conor Newman’s paper, so I’m very willing to be corrected), this practice of ritually drawing a sword across a sacred stone is first attested in Irish literature, in the Baile Chuinn Chétchathaig mentioned above. Indeed Newman makes the point that it may be the source of the later Arthurian sword-in-the-stone legend.

The bulk of the examples that Newman provides are from Ireland (although that may just be a geographical bias on his part). His other examples are from Wales and one Scottish one, from Finlaggan on Islay, which he connects with the medieval lordship of the Isles.

Absent any other evidence, it might be reasonable to conclude from this that the marking of stones with a sword is a ritual practice that originated in Ireland and was later transplanted to Britain. Its apparent connection with the high-kingship of Ireland and (albeit less convincingly, to my mind) the lordship of the Isles creates a pretext to look for a similar context for Sueno’s Stone.

A possible Moray connection to the kingship of Alba

And, as it happens, there is a context that fits. In 2001, Dr Alex Woolf wrote a paper called The ‘Moray Question’ and the kingship of Alba in the tenth and eleventh centuries. In it he observed that throughout the tenth century and into the eleventh, the kingship of Alba (the precursor kingdom to Scotland) alternated between two branches of the Alpin family, descended from two sons of Cináed mac Alpin, Causantín and Áed.

Woolf argued that this alternating succession was based on the model used in Ireland to determine who should succeed to the high-kingship. In the Irish model, high kings were drawn alternately from two branches of the Ui Neill family; Cenél nEógain who ruled in the north in Ailech (County Donegal), and Clann Cholmain who ruled in Mide (County Meath) in central Ireland.

The geographical separation was important because it kept both branches strong and ensured the dynasty’s influence and power base would remain spread over a wide area. Woolf wrote:

The success of the alternating kingship relied upon the inability of the kings of either Ailech or Mide to control the other region effectively. Had a unilateral, unilineal kingship begun to develop in either area, it would almost certainly have led to a reduction of the territorial extent of effective royal power.

Woolf posits a similar arrangement for the descendants of Cináed mac Alpin, arguing that the dynasty descended from Cináed’s elder son Causantín was based in southern Alba, around Perth, and the dynasty descended from the younger Áed was based in the north, specifically in Moray. Their physical separation was thus assured by the mountain range that divides the two territories. The title of rí Alban, king of [the whole of] Alba, passed between these two branches from 862 until 1034 AD.2

A link between Sueno’s Stone and the kingship of Alba?

Woolf’s theory provides a context which might explain both the inauguration scene and the sword marks on Sueno’s Stone. Any Clann Áeda member hoping to secure the over-kingship of Alba would need the support of the local nobility, otherwise he risked being murdered in favour of another would-be claimant.

(The apparent tidiness of the Irish succession, Woolf argues, belies the violent struggles for dominance that must have taken place at the regional level.)

Sueno’s Stone sits at the core of the old Pictish kingdom of Fortriu, easily accessible by land along the Moray Firth coast and by sea from Easter Ross, and in a landscape rich with symbols of ancient power. It could hardly be more ideal for an assembly place where oaths of fealty to the chosen Clann Áeda dynast could be publicly sworn, marked by the drawing of swords across the panel beneath the stone’s inauguration scene.

In this scenario, the stone could have been erected in the time of Cináed mac Alpin (843-858 AD) to stake his claim to northern Pictland and install his son Áed as its ruler. Indeed, the theory that the stone was erected by Cináed is already the most widely-accepted one, although the focus is usually on the battle scenes and the idea that Cináed brutally defeated the local Picts to win the territory.

In any case, both theories could be perfectly compatible – we just don’t know how Cináed came to be king at all, let alone how he won northern Pictland or whether he installed any of his family there.

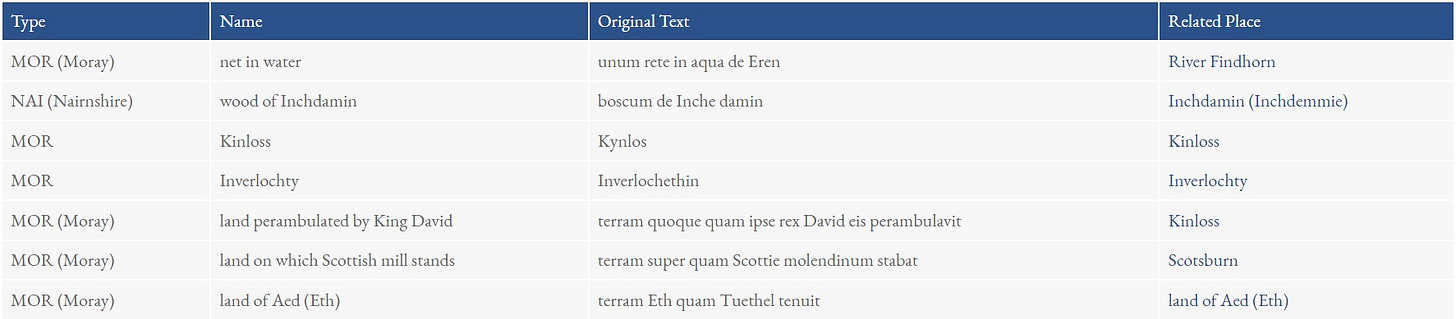

There is a tiny shred of evidence to support the Clann Áeda theory, though. When David I founded Kinloss Abbey in 1150, his foundation grant of land is said to have included a “terram Eth quam Tuethel tenuit” (see table below). ‘Terram Eth’ means ‘Áed’s land’, and Kinloss Abbey is just two miles from Sueno’s Stone.3

That said, Áed was a common Gaelic name—it was also the name of Áed’s own brother-in-law, Áed Findliath—so land associated with an Áed in the vicinity of Sueno’s Stone doesn’t necessarily imply a connection with Clann Áeda. I should also point out that Dr Neil McGuigan argues quite persuasively in chapter 1 of his biography of Malcolm Canmore that it was actually the other branch of the Alpinid dynasty, Clann Causantín, that was based in Moray.

Was Sueno’s Stone also a boundary marker?

What about Newman’s other context for sword-marked stones—their role as boundary markers, on which territorial treaties were enacted and ratified by drawings of the sword?

I find this one less convincing, simply because I find it hard to see how Sueno’s Stone could have marked a significant geopolitical land boundary in the ninth or tenth century. The neighbouring polities were Dál Riata (Argyll), far to the south-west, and the Norse earldom of Orkney to the north, of which Professor Barbara Crawford wrote in 1986:

[To] all intents and purposes the territory north of [the Dornoch Firth] was part of the Norse world from the ninth to the thirteenth century. South of that waterway was a disputed region, and the firthlands of Easter Ross were frontier territory during the same period.

Undoubtedly these territories would have waxed and waned in size, and there must have been many disputes and skirmishes (and worse) at their fringes. But these frontier regions were far from Forres; down the Great Glen for Dál Riata, and around the Black Isle for the Norse earldom.

The Norse earldom must at one time have extended as far south as Dingwall, given its name, but there is scant evidence for Norse occupation or settlement further south. The earls seem never to have gained control of the entrance to the Great Glen at Inverness, let alone anywhere in Moray.

There is an argument that the entire southern shore of the Moray Firth was a maritime frontier between northern Alba and Norse Orkney, and at least one Norse attack on this coast is reliably documented for 962 AD at Cullen. But in that sense, the whole of Moray is on the boundary, rather than Sueno’s Stone specifically. Could a boundary context for the stone still apply? I’m not sure.

It’s also worth mentioning that as yet, I’ve never come across a reference to Sueno’s Stone as a boundary marker in any period. Even as late as the New Statistical Account of 1845 it’s reported as being firmly in the parish of Rafford, “on the property of the Earl of Moray.” But this is a topic for another time!

The pieces seem to fit… for now, at least

Understanding late first-millennium Moray often feels like trying to do a massive jigsaw puzzle for which the box and most of the pieces are missing. In these blogs I’m mostly attempting to fit random different pieces together to see if anything fits.

For this one, I’ve tried to fit together three things: Ruth Loggie’s discovery of sword marks on Sueno’s Stone; Conor Newman’s research into sword marks in Ireland as evidence of medieval high-kingship rituals and territorial treaty enactment; and Alex Woolf’s suggestion that the Clann Áeda branch of the tenth-century Alpinid dynasty of kings of Alba had its power base in Moray.

I’m not sure about territorial treaty enactment, but there does seem to be a tentative case for connecting the sword marks on Sueno’s Stone with the nomination of a tenth-century Clann Áeda dynast to assume the overkingship of Alba.

I could be wildly wrong! But whatever the real explanation, I think Ruth Loggie has definitely made an important discovery, and Conor Newman has provided some very intriguing context. As ever, I’d love to hear anyone’s thoughts in the comments.

References

Broun, Dauvit. The Most Important Textual Representation of Royal Authority on Parchment 1100–1250? (2015)

Crawford, Barbara. The Making of a Frontier: The Firthlands from the Ninth to Twelfth Centuries (1986)

Duncan, A.A.M. Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom (1975)

Isaksen, Leif. The Hilltop Enclosure on Cluny Hill, Forres: Description, destruction, disappearance (2017)

Loggie, Ruth. A Revisit to Sueno’s Stone, unpublished MSc dissertation, University of Aberdeen (2020)

McCullagh, R.P.J. Excavations at Sueno’s Stone, Forres, Moray (1995)

McGuigan, Neil. Mael Coluim III ‘Canmore’: An Eleventh-Century Scottish King (2021)

Mitchell, Juliette, et al. Monumental cemeteries of Pictland: Excavation and dating evidence from Greshop, Moray, and Bankhead of Kinloch, Perthshire (2020)

Newman, Conor. The Sword in the Stone: previously unrecognised archaeological evidence of ceremonies in the late Iron Age and early medieval period (2009)

New Statistical Account, Parish of Rafford (c. 1845)

People of Medieval Scotland database: poms.ac.uk

Sellar, David W.H. Sueno’s Stone and its Interpreters (1993)

Woolf, Alex. From Pictland to Alba 789–1070 (2007)

Woolf, Alex. The ‘Moray Question’ and the Kingship of Alba in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries (2001)

Update 2nd March: Thanks to Professor Leif Isaksen, who has pointed out that Rod McCullagh did mention these marks in his report of the excavation carried out around Sueno’s Stone in 1991: “…the absence of any plough scars on the stone (the radiating notches on the lowest panel of the cross-carved face are most probably axe or sickle sharpening marks) seems to be inconsistent with the stone’s supposed long, recumbent sojourn below ground level.”

Update 26th Feb: This date range should actually be 862-1005 AD, as the rotation of the kingship between the two branches stopped after the death of Cináed mac Duib in 1005, perhaps because Clann Áeda did not have a suitable successor to offer at that time.

Update 2nd March: I think the Áed whose land was granted to Kinloss Abbey is much more likely to have been the Áed identified by A.A.M. Duncan in Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom (1975): “…early in the reign of David I…an earl Aed or Heth occurs as a witness to charters and would seem (because other provinces are associated with other earls) to have held [the earldom of Moray].” (pp 165-166). One to dig into another time.

Thanks Fiona, for another thought-provoking blog. I like the direction this is going! Anent stones with 'sword' marks. There are definitely other examples elsewhere in Scotland (e.g. Lethendy https://canmore.org.uk/site/79896/lethendy-house) and, as I recall, Wales. That doesn't mean the practice didn't originate in Ireland, but it was also known in southern Pictland.

Yet more fresh food for thought Fiona! As I’ve said previously I am fairly certain there was a separate northern, Moray based kingship. That there is no direct historical record is not surprising given the paucity of any surviving sources and especially when those that we do have were written from a southern (Alban) perspective. The acceptance of the “usurper” MacBethad by Alba certainly suggests that his claim to overall kingship must have had a credible constitutional basis. Similarly the ongoing struggles of the Alban kings through the 11th and 12th centuries to get the folk of Moray to accept their sovereignty also suggests a tradition of an independent kingship or polity.

So having the mound that Sueno’s stone stands as a place of coronation certainly makes sense to me. I think it is also worth noting that Cluny Hill, sitting directly behind the mound, is very prominent in the landscape and can be picked out from afar, especially the northern coast of the Moray Firth. Perhaps that visibility was also significant

Really enjoying your posts. Keep up the good work - once you regain your throne from the usurper 🐈⬛