'Tubernafein': A folkloric, literary or historical place-name?

In which I investigate how a lost well in Moray might have got its intriguing name.

[UPDATE 29/10: This blog has attracted some criticism over my use in places of ‘Celtic’ and ‘pan-Celtic’ when I really mean ‘Gaelic’ and ‘pan-Gaelic’. I’ve made some changes and added a footnote (update 04/11: now two footnotes) about this.]

This blog is about a lost place-name near Forres in Moray that I’ve been investigating recently.

My initial thought was that if I can figure out how it got its name, it might give me a clue as to who was living in this part of Moray in the deeply obscure period prior to the late twelfth century.

As usual with these blogs, I write as I’m researching, so I don’t know when I start where I’m going to end up. In this case, I end up somewhere quite exciting. So come along for the ride as I investigate the lost well of Tubernafein.

A thirteenth-century charter to Kinloss Abbey

The starting point is a charter of 1221 to Kinloss Abbey. In it, Alexander II of Scots grants the monks a portion of land on his estate at Burgie, just east of Forres. The boundaries of this portion of land are set out using a series of landmarks:

[A] magna quercu in Malevin quam predictus comes Malcolmus primo fecit cruce signari usque ad Rune Pictorum et inde usque ad Tubernacrumkel et inde per sicum usque ad Tubernafein et inde usque ad Runetwethel et inde per rivulum qui currit per maresiam usque ad vadum quod dicitur Blakeford quod est inter Burgyn et Ulern.

Which translates to:

From the great oak tree in Malevin which the aforementioned earl Malcolm marked with the sign of the cross, to the Rune Pictorum, and from there to Tubernacrumkel, and from there along the ditch to Tubernafein, and from there to Runetwethel, and from there along the burn that runs through the marsh to the ford that is called Blackford, which is between Burgie and Ulern.

Two of these landmarks are wells (which we should imagine as natural springs), and two are referred to as ‘Runes.’ We’ll meet one of these ‘Runes’ at the end of this blog, but I mostly want to focus on one of the wells.

Parsing the well of Tubernafein

This is a well that the charter calls Tubernafein – a name that caught the attention of a nineteenth-century antiquarian, James Brichan.

In 1858, Brichan wrote an article for the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland about his efforts to retrace the boundary set out in the charter.

In it, he mentions that attached to the original charter was another parchment, containing some notes offering further explanations of the landmarks. For Tubernafein, these notes apparently specified (in Scots):

Tubernafeyne of the Grett or Kemppis men callit Fenis.

To which Brichan commented:

“[T]he word Tubernafein… indicates and commemorates the former existence of a race of men, whosoever they may have been, known in 1221 as the Kemppis men or Fenis (and still spoken of in some parts as the Fingalians), and whose name and memory, even in the thirteenth century, seem to have existed solely in the form thus indicated.”

At first, I found this all completely mysterious. None of these terms meant anything to me, other than Tuber, which I could recognise as Gaelic tobar meaning ‘well,’ and Fingalians, which I (wrongly) assumed to refer to the Finngaill, the ninth-century Irish term for Norwegian Vikings.

After puzzling over it for a bit, I decided to ask in the Scottish Place-Names Group on Facebook. There’s a very learned bunch of people in that group and they’ve helped me out before.

And thanks to some excellent responses from Alan G. James, Iain MacIllechiar, Helen McKay, Peter McNiven and Michael S. Newton, I learned that ‘Tubernafein’ is Gaelic Tobar na Fèinne or Well of the Fianna.

Three Fianna types: mythological, literary and historical

I knew nothing about the Fianna at that point, but I’ve done quite a bit of reading since.

As well as learning from my Facebook replies, I’ve read Mark Williams’s The Celtic Myths that Shape the Way We Think, Ann Dooley and Harry Roe’s introduction to (and translation of) the early thirteenth-century Acallam na Senórach, and Kuno Meyer’s 1910 collection of Fianaigecht, or Fianna-literature.

From all of that, I’ve learned that Fianna is a deeply resonant term that spans folklore, literature and historical reality.

In Celtic folklore, the Fianna are the hunter-warrior companions of Fionn mac Cumhaill (Finn MacCool), a heroic figure who lives outside of settled society and can communicate with the Túatha Dé Danann; the Otherworld folk/ancient pagan gods who inhabit mounds in the landscape.

In the oldest strands ofCelticGaelic12 mythology, Fionn himself may have been a god. He is certainly often portrayed as a giant; the Giant’s Causeway in County Antrim is named after him.In the literary domain, Fionn and his Fianna, including his son Oisín and retainer Caílte, are central characters in the Fenian Cycle, a vast body of medieval Irish literature that preserves the more Christianity-friendly elements of the oral folk-tale tradition of Fionn stories outlined above.

Early writing was Christian writing, and the literary Fianna evolved with the religio-political concerns and literary tastes of contemporary clerics. In early texts they’re presented as violent pagans, but by the twelfth century they had been reconciled with the Christian worldview and morphed into chivalrous knights, satisfying demand for tales of heroic deeds and courtly love in a Christian milieu.In the historical sense, fianna (or more properly fíana, as I learn from Kuno Meyer that the double ‘n’ is a later form) has two inter-related meanings.

Firstly, in early medieval Ireland, fíana were young noblemen and women who had not yet inherited any land. Until they came into their inheritance they were legally allowed to roam the wild, unpopulated parts of the countryside, hunting and fighting as they saw fit.

In another sense, the word fíana meant members of a fían or warband, such as that of Máelumai mac Báitáin, who, according to Kuno Meyer, led his fían to Britain in 608 AD to fight alongside Aedán mac Gabráin, king of Dál Riata, against the Angles of Bernicia (Northumbria).

Indeed, Meyer saw this meaning of fíana as being in use in both Ireland and Gaelic Scotland going back to the time of the Roman occupation of Britain:

“I have no doubt that bands of Scotti who made common cause with the Picts in the third and fourth and centuries in harassing Roman Britain were also called fíana.”

Which Fianna is the well named after?

All this means that if I want to contextualise the well at Burgie, I have four possible meanings of fíana to consider:

Fionn mac Cumhaill’s companions in

pan-Celticpan-Gaelic oral traditionFionn mac Cumhaill’s companions as portrayed in medieval Irish literature

A real band of young roving hunter-warrior aristocrats

A real warband from either Ireland or Gaelic-speaking Scotland

So which of these Fianna—or fíana—is the well named after?

My first observation is that the name Tubernafein is Gaelic, suggesting it was coined not by native Picts, who spoke a Brythonic language similar to Welsh, but by Gaelic speakers who settled in Moray probably from the mid- to late first millennium AD onwards.

My second observation is that it appears as a seemingly established name in a charter of 1221, providing a terminus ante quem; a date before which the naming must have occurred.

That gives a roughly 600-year span—from c. 600 to c. 1200—for the naming of the well.

What was the impulse behind the naming of Tubernafein?

The next thing to do is to assess the evidence for whether the impulse for the naming was:

a) factual: the well was used by an actual fían band—whether young roving aristocrats or a local warband.

b) folkloric: the well—due to some aspect of its setting or property of its water—was imagined by local storytellers to have been frequented by the mythological Fionn and his companions.

c) scholarly: the well was named by a person or group wishing to imbue this landscape with literary references that had particular meaning for them.

This is quite some challenge, but it is possible to make some observations based on the well’s landscape location.

One attribute of Fionn’s Fianna and the real aristocratic fíana is that they roamed the wild places outside of settled society. However, unlike other places in Scotland named for Fionn and his companions, this Tubernafein is mostly definitely not in the wilderness.

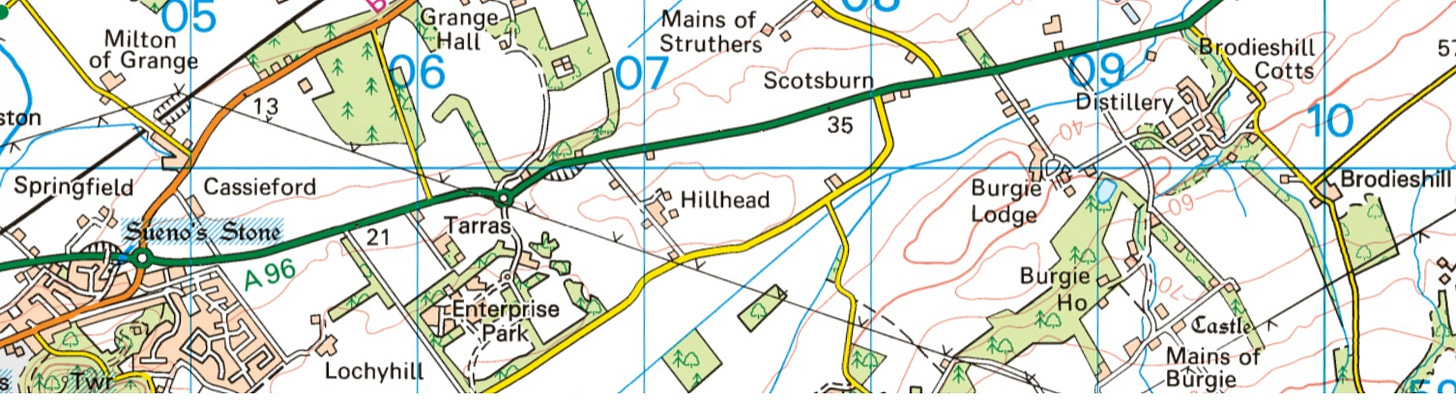

Although its exact location is unknown, it is certain that it was on the Burgie estate, which occupies a gentle north-facing slope only three or four miles inland from the Moray Firth coast.

Not only is this not wilderness country, it was also not unpopulated, even in the early Middle Ages. Like all of this fertile lowland strip, it shows signs of having been extensively settled since the Neolithic period.

The map below shows sites in the immediate area of Burgie as catalogued in the Aberdeenshire Council Historic Environment Record for Moray. They range from enclosures, souterrains and hut stances to an “extensive” Bronze Age cist cemetery and finds including a decorated spindle whorl and a “bronze human foot.”

This doesn’t seem like the kind of landscape where one would expect to find liminal-dwelling hunter-warriors, whether real or mythological.

It also doesn’t seem typical of Fianna place-names. On p. 33–35 of this booklet of Place-Names of Scotland’s National Parks, for example, we’re told:

When telling the legends of the Fianna, place names were used to help listeners to imaginatively place themselves within the setting of the tale. Places were also named after Fionn and the Fianna. They were often associated with large landscape features (such as mountains and rivers), emphasising their heroic, superhuman status. [my emphasis]

The booklet cites the spring of Tobar nam Fiann in Glenshee as an example—noting that the glen itself is named after the sidhe or fairy-folk of Celtic Gaelic myth. The Walkhighlands website also tells us that one of the peaks in Glenshee is called Beinn Gulabin, the name of the place where Fionn’s nephew and love rival Diarmaid died in Fionn folklore. Here it is below, looking suitably large, heroic and superhuman.

The two other examples offered in the booklet are Ath nam Fiann (ford of the Fianna) in Glen Avon in upland Moray, and Allt Chill Fhinn (burn of Fionn’s church).

The first of these, Glen Avon, is another wilderness place, as shown in the picture below, confirming the naming pattern.

As to Allt Cill Fhinn, it’s unclear where the booklet is referring to. There are three places in Scotland called Cill Fhinn (anglicised to Killin): one at the head of Loch Tay (NN 57288 33111), one on Loch Garve in Ross-shire (NH 39859 60775), and one on Loch Brora in Sutherland (NC 85606 07120).

These also fit the ‘wilderness’ pattern in that they’re all in mountainous places. However, their names can’t relate to Fionn mac Cumhaill as Cill means church and Fionn is emphatically not a Christian. (The place-name scholar W.J. Watson suggested that all three places may be named after a lost Saint Fionn.)

Is Burgie too tame a landscape for Fionn and his Fianna?

I might conclude from this that the comparative tameness of the landscape around Tubernafein at Burgie suggests that its naming is neither folkloric, nor literary, nor related to a real fían band of young aristocratic nomads.

(Having said that, this does seem a bit prescriptive, as surely lowland-dwellers must have wanted to imagine their mythological heroes in the landscape too. And it’s worth noting that not far inland and upland from Burgie we start to see sidhe-names appearing: there’s a burial cairn called Shian Hillock at Littlemill in Nairnshire (NH 91367 49807), and Dulsie on the Findhorn (NH 93051 41558) is another sidhe-name.

If anyone knows of any other lowland Fianna places in Scotland, I’d be interested to hear about them, as I don’t want to rule out folkloric or literary coinings unnecessarily.)

Is Tubernafein named after a real warband?

However, if we do take Tubernafein’s non-heroic landscape as a deal-breaker, then the only remaining explanation is that the well is named after a real fíana, or early medieval Gaelic warband.

This is actually not an unreasonable proposition, as warbands accompanied kings and tribal leaders, and Forres and its environs appear multiple times in the early sources as a place where early kings of Scots were present—and indeed were killed—throughout the tenth century.

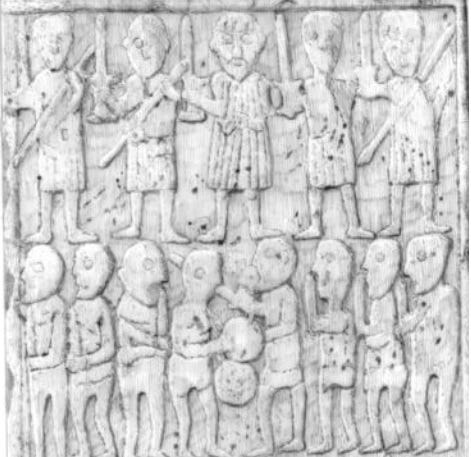

What’s more, a warband of just this type is depicted on Sueno’s Stone, only two miles from Burgie (detail below from the recent drawing of the stone by John Borland).

A very daring suggestion to finish

If I wanted to be daring, I might suggest that we see the warband depicted on Sueno’s Stone and the warband suggested by the name Tubernafein as the same group of warriors.

And even more daringly, I might suggest that we consider both of them in light of another landmark at Burgie mentioned in the 1221 charter: the mysterious Rune Pictorum.

This name means ‘Rune of the Picts,’ but it’s not entirely clear what ‘Rune’ means. In his 1858 article, James Brichan mentions that the attachment to the original charter explains this name in Scots as:

“the carne of the Pechts, or the Pechtis fieldis”

This suggests that we should see the Rune Pictorum as a cairn of some kind. Is it too much to think that it might have been a burial cairn—in which were buried a band of Picts defeated by the Gaelic fíana immortalised on Sueno’s Stone and in the name Tubernafein?

And might this, finally, be evidence of the long-suspected defeat of the Northern Picts by the army of the new, Gaelic-speaking king Cináed mac Alpin in or around 842 AD?

The dates certainly line up: I’d posited a date range of c. 600–c. 1200 for the naming of the well, so 842 AD definitely fits. And a battle between Scots and Picts in this exact area has long been posited: in 1991, for example, the historian David Sellar interpreted Sueno’s Stone as commemorating:

“[A] real battle… the final victory north of the Mounth by the Scots over the Picts.”

Let’s not get carried away, though…

It’s an exciting thought, but in reality, using a couple of place-names in a thirteenth-century charter as evidence for an otherwise unattested battle probably isn’t going to stand up in court (even if such a battle has long been suspected).

And despite its unassuming landscape location, it’s far more likely that Tubernafein is named after the folkloric or literary Fianna than Cináed mac Alpin’s ninth-century warband.

But I’ve had quite the intellectual thrill from investigating it, I’ve learned a huge amount about Fionn mac Cumhaill and Celtic Gaelic folklore, and I’ve ended up at a very intriguing and unexpected conclusion. So time well spent!

References

Brichan, James. Notice of a curious boundary of part of the Lands of Burgie, near Forres, in a Charter of King Alexander II., 1221 (1858)

Dooley, Ann, and Harry Roe. Tales of the Elders of Ireland: A new translation of Acallam na Senórach (1999)

Meyer, Kuno. Fianaigecht: Being a collection of hitherto inedited Irish poems and tales relating to Finn and his Fiana, with an English translation (1910)

Rodway, Simon. The Mabinogi and the shadow of Celtic mythology (2018)

Sellar, David. Sueno’s Stone and its Interpreters (1993)

Stuart, John. Records of the Monastery of Kinloss (1872)

University of Galway press release. “Tales of Finn mac Cumaill linked to places of exceptional natural resources” (2015)

Watson, W.J. The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (1926)

Williams, Mark. The Celtic Myths That Shape the Way We Think (2021)

I originally used ‘Celtic’ rather than ‘Gaelic’ here and elsewhere as I was under the impression that Fionn, the Fianna and the sidhe had parallels in Welsh oral tradition, and so ‘Celtic’ seemed the more correct term. Having read some more, it seems that while there are some parallels between the bodies of Irish and Welsh medieval literature into which older folk-tales have been incorporated, in Dr Simon Rodway’s words: “it is impossible to prove that such similarities are due to independent descent from a period of Celtic linguistic unity rather than to more recent contact between Ireland and Wales, to mutual borrowing from a third source, or to coincidence.” I’ve added Simon Rodway’s chapter to the bibliography above.

Following from the footnote above, it’s worth noting that Professor Elizabeth FitzPatrick of the University of Galway sees ‘Finn’ place-names as possible remnants of an older Celtic naming tradition. In her words: “Finn places on the edge of Western Europe may be the most enduring survival of a wider landscape expression of the Celtic place-name ‘vind’ and its associated phenomenon of boundaries and enriched natural resources, extending from Gorumna Island in south Connemara to Galatia in Asia Minor." I’ve added this to the bibliography too.

Hi Fiona, I enjoyed your piece. You asked about potential lowland Fianna of Fionn place-names. I'm trying to finalise a talk for Ainmean Charraig's day conference in Maybole, Carrick 14th Sept and 3 place-names possibly point in the direction you are discussing here. They are Dinvin (Girvan), Trees (formerly Duneyne and variants, Maybole) and Knockeen, Barr. The first two might be Dùn na bhFiann and the third Cnoc Fhinn (so 2 x fort of the Fianna and Fionn's knowe (probably a cairn on the farm)). We have established Ainmean Charraig to research Carrick's place-names and heritage. https://www.facebook.com/groups/954532863061564/ Kind Regards Michael