An eighth-century royal circuit in Moray and Easter Ross?

In which I examine the possible significance of 'David' sculpture in the Moray Firthlands

[UPDATE 30.12.24: Thanks to all who have commented on this post, below and in other places. I’ve made a few proofing edits and corrected a bigger error in my (non-) understanding of the David story in the Book of Samuel: Saul was not, in fact, David’s father! (Back to Sunday school for me…) I’ve also added an alternative interpretation of the trumpeters on the Cadboll stone based on this blog by Helen McKay. Thanks to Alastair Fraser who has pointed out the possible significance of the name Kincardine; a hybrid Gaelic-Pictish name meaning something like ‘end of the forest,’ suggesting that this may have been where kings came to hunt, rather than to stay on an estate and enjoy their food renders. I’ll come back to this idea soon, as it invites a reappraisal of the place-name element ‘carden,’ whose specific meaning in Pictish is currently subject to debate. Could it have denoted a royal hunting reserve?]

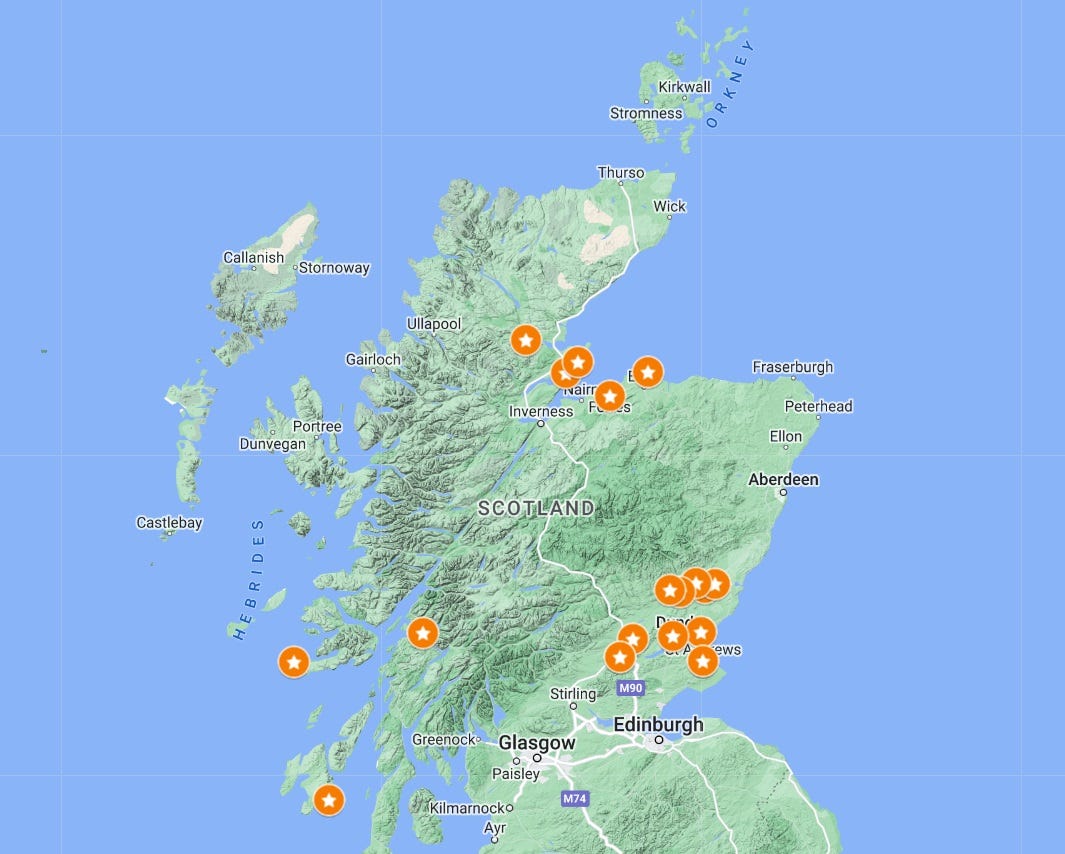

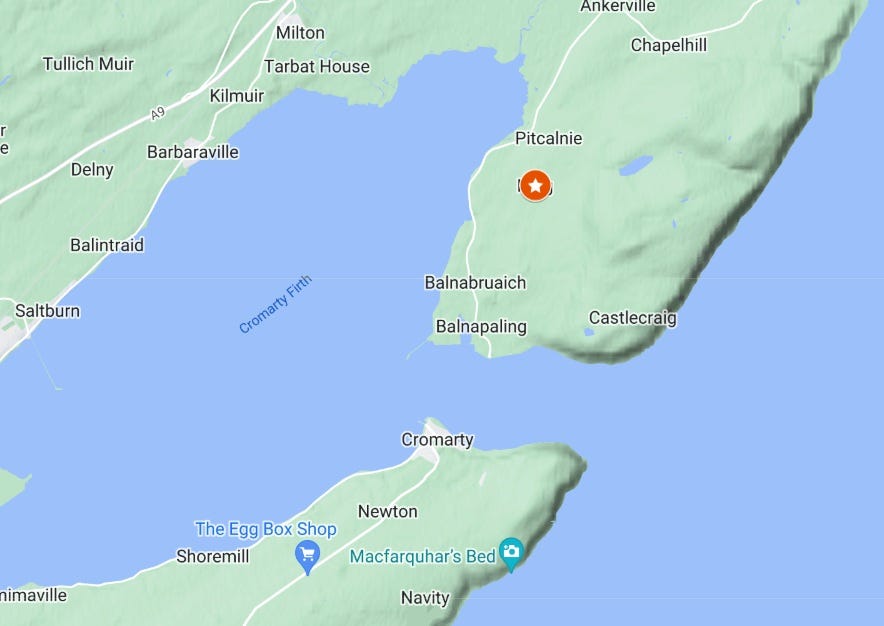

One of the most striking (and unexpected) findings of my MA research was that in the later first millennium AD, ‘Moray’ seemed to stretch across the Moray Firth to include parts of what is now Easter Ross.

More specifically, it seemed to include the Tarbat peninsula and the coastal strip around the Dornoch Firth, perhaps even as far north as Golspie in Sutherland.

I came to this conclusion by mapping the distributions of various types of early medieval evidence in the region, including ‘central places’, place-names, Pictish symbol stones, sculpture with imagery of the biblical King David, ogham inscriptions, and (less conclusively) iron hand-bells associated with the early Christian church.

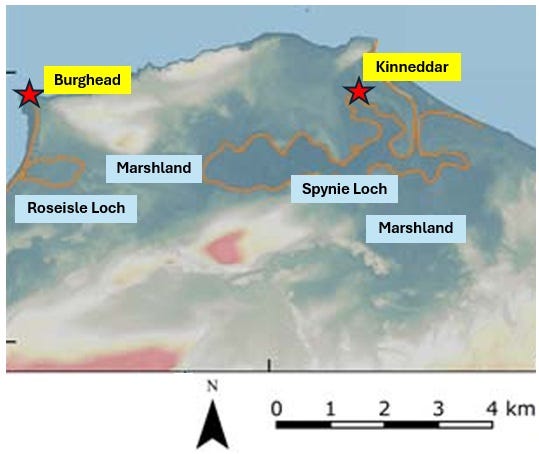

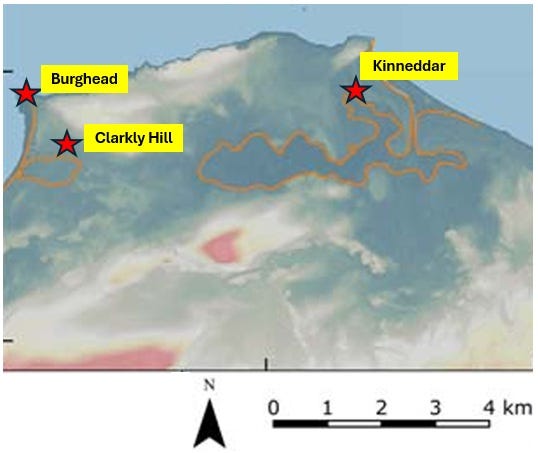

It all seemed to point to the existence of two small kingdoms in the Moray Firthlands in the long eighth century: Moreb (Moray), centred on Burghead, and Ros (Ross), centred on Inverness (below).

Hints of an eighth-century royal circuit?

Recently, it struck me that one of these distributions—sculpture with David imagery—might preserve an imprint of a royal circuit; a regular tour undertaken by eighth-century kings of Moreb to demonstrate their authority, receive hospitality and tribute, and connect with their followers.

In this blog I want to think through this idea, see if it holds water, and if so, understand what the implications might be. As always, I’ve started writing without really knowing where I’m going to end up, so you are coming along on this research journey with me.

The sculptural evidence

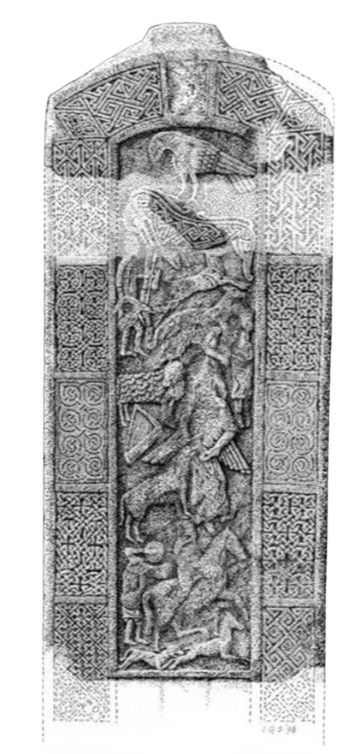

The first task is to set out the evidence. There are four monuments in the north of Scotland with imagery that has long been linked to the biblical David: at Kinneddar in Moray, at Nigg and Hilton of Cadboll on the Tarbat peninsula, and at Kincardine at the head of the Dornoch Firth (below).

Three remain largely intact, while the fourth, at Kinneddar, is a fragment of a relic-shrine or cross-slab (below). All four are usually dated to the eighth century on stylistic and archaeological grounds, and all four occur in the area I’d identified as the kingdom of Moreb, spanning the Moray Firth.

On the Kinneddar, Nigg and Kincardine monuments, David is recognisable by his harp and by the fact that he is rending the jaws of a lion. This is a reference to 1 Samuel 17:34–25, in which David tells his father Saul that he has protected Saul’s his father’s sheep by defending them against a lion.

Less certainly, the art historian Isabel Henderson identified the magnificent cross-slab from Hilton of Cadboll on the Tarbat peninsula as a fourth David-themed piece, as I’ll explain later.

All of these monuments are of an extremely high quality, in many ways representing the high point of Pictish Christian sculpture. The superb cross-slab at Nigg in particular has been hailed by Isabel Henderson as “second to none in the history of Western medieval art”.

The distribution becomes even more striking when seen in the wider context of David imagery in Pictland. These four monuments are the only eighth-century sculptural representations of David anywhere north of the Mounth, with the others located far away in Angus, Fife and Argyll (below). This too suggests that they are connected in some way, despite being separated by the Moray Firth.

The link to Pictish royalty

Next we need to link these David images to Pictish royalty. There is compelling evidence that the biblical David was seen in early medieval Europe as a model for kings to emulate. The historian Donald Bullough noted that:

Pope John II in 533 drew the attention of the bishops in the province of Arles to the exemplar that ‘worldly rulers’ would find in the Book of Kings’s account of Saul and David; bishops and others in the court-circle around the seventh-century Frankish Kings Chlothar II and Dagobert compared their monarchs with David; Pope Stephen II addressed King Pippin [d. 768] on several occasions as ‘the new David’.

This connection between David and exemplary kingship did not, however, seem to have extended to European monumental art—with one exception. Bullough wrote:

There is one part of north-western Europe where representations of David may more consciously have been adopted as a prefiguration or ‘type’ of a contemporary ruler. This is Pictland.

Bullough pointed out that representations of David in Pictish sculpture very often occur alongside images of an armed horseman either going to war or going to hunt; two fundamental activities of an early medieval Western king. Combined with the exceptional quality of the craftsmanship of the Pictish David sculpture, he felt that this pointed at a royal association:

…the elaborateness and quality of these stones, and the association on some of them of the imagery of David and of the hunt, at least raises the possibility that they were a visual expression of the authority of the last independent kings of the Picts.

Having made this connection, however, Bullough was at a loss to explain the settings or intended meaning of the Pictish David monuments:

We simply do not know why these sculptured stones were erected where they were, and any interpretation of their iconography…is necessarily highly speculative.

The significance of the ‘David’ locations

In a paper for the Pictish Arts Society conference in October, Professor Jane Geddes aimed to answer Bullough’s first question by examining the locations and iconography of David sculpture across Pictland.

One of her key insights was that David sculpture appears in locations that Jane saw as either central places (like St Andrews), boundary locations (typically on parish boundaries), or in-between places that Jane deemed ‘processional’.

As an example of a ‘processional’ location, she offered the Aberlemno Roadside cross, describing it as:

“[located] on the roadside, on the Finavon ridge overlooking Strathmore, in what is now looking increasingly like a via regia between Forfar and Brechin… This is a stone commemorating a royal adventus and ceremonial hunt, in the vicinity of the Finavon and Turin hillforts, associated with a possible royal dwelling adjacent at Flemington farm.

Jane went on to focus on the ‘ceremonial hunt’ aspect of the processional monuments, seeing the Nigg and Cadboll stones as monuments marking ritual landing points at either side of a proposed royal hunting reserve on the Tarbat peninsula; with the king landing at Nigg and the queen at Cadboll.

My own hunch, however, is that the Firthlands David monuments are not about the hunt per se, but rather relate to a third fundamental activity of an early medieval Western king: the royal circuit or iter.

The early medieval royal circuit

I first came across the idea of the royal circuit in Professor Alex Woolf’s 2007 book From Pictland to Alba 789–1070. He proposed that tenth-century kings of Alba had no central place of government, but instead continually travelled between high-status places—mostly, if not all, monasteries—in central Scotland: St Andrews, Abernethy, Forteviot, Scone and Dunkeld.

Woolf’s source was John W. Bernhardt’s 1993 book Itinerant Kingship and Royal Monasteries in Early Medieval Germany c. 936–1075. In it, Bernhardt identified royal itineration as a method of government practised in chiefdoms and kingdoms around the world—both in the middle ages and later—in societies with these characteristics:

A largely natural economy; the dominance of peasant farmers by warriors or by a particular clan or family; governmental authority deriving from personal relationships and often from feudal relations; magical or sacred conceptions of rulership, and, in some cases at least, only marginal reliance on the written record in government.

The purpose of the royal circuit, according to Bernhardt, was multi-fold:

…kings or chiefs moved constantly throughout their territories making their presence felt and reinforcing the personal bonds of their rulership. They gathered their people around them, took part in solemnities, conferred gifts and honours, pronounced justice, fought enemies and rivals and ensured general security.

Itineration was thus fundamental to the exercise of power and legitimation of the king’s rule:

…the king-in-motion identified—even embodied—the society's centre of power; and the royal progress itself became the major institution of government. Through it, the king took symbolic as well as actual possession of the realm.

My takeaway from Bernhardt’s book is that the practice of itineration was so common in Europe in the early middle ages that it would be unusual to find a king who did not frequently tour his territory. So even though I’d identified Burghead as the secular caput of Moreb, I should expect a king based at Burghead to be regularly on the move, accompanied by his extended household.

The need for sustenance

My research then led me to a chapter by Thomas Charles-Edwards in the 1989 book The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Professor Charles-Edwards set out another, more basic, purpose for the royal circuit—to ensure the royal household had enough to eat.

In the whole of the British Isles all but very minor kings kept on the move in order to survive: itineration was an essential economic basis of kingship. No large household could stay in one place for more than a few weeks without a long-distance trade in all essential foodstuffs.

Indeed, when I think of Burghead, the huge promontory fort jutting into the Moray Firth from its southern shore, the issue of having enough to eat seems a pretty pertinent one.

Today, Burghead’s hinterland is some of the best arable farmland in Scotland, the low-lying Laich of Moray. But until the twelfth century at the very earliest, this land was mostly underwater, forming the sea-lochs of Roseisle and Spynie, with boggy ground between them (below).

It’s hard to imagine there was enough agricultural land locally to sustain the fort of Burghead, the nearby early medieval settlement on Clarkly Hill, and the large early medieval monastery at Kinneddar. Itineration would surely have been a matter of survival for the king and his entourage.

In that case, it would also make sense that the stops on the king’s iter would be located in areas of rich farmland. The mostly low-lying Tarbat peninsula, and the fertile coastal strip along the Dornoch Firth, seemed like plausible areas for a royal circuit. And the sites endowed with David sculpture are also neatly spaced—Kincardine is as far from Nigg as Nigg is from Kinneddar.

Four potential circuit sites

From the three sources noted above—Woolf, Bernhardt and Charles-Edwards—I learned that the places which hosted the king on his itineration would be high-status places; typically monasteries, royal estates, or estates held from the king by his noble followers.

So do the four sites with David sculpture fit any of these categories? Let’s look at each in turn.

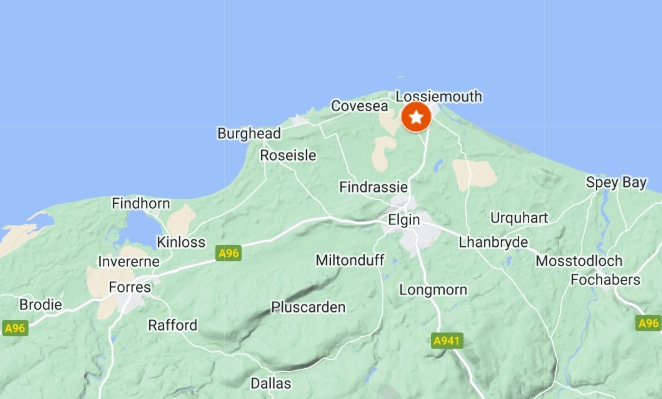

1. Kinneddar

The nearest ‘David’ site to my proposed caput of Moreb at Burghead is the monastery of Kinneddar.

I’ve written about this site before, when I was just starting out on my research journey. Only its vallum (encircling ditch) has been excavated, but that dig revealed that the vallum was created c. 600 and enclosed a very large monastic site: equal in size to Iona.

It’s frustrating that we don’t really know any more than that—but even this suggests the sort of site in which a king might have had dedicated accommodation for himself and his entourage.

In the south of Pictland, for example, we know from the chance survival of a fragment of ninth-century text that king Wrad of Picts (r. c.839–c.842) had a royal hall within the monastery of Meigle in Angus. We might imagine the same sort of arrangement at eighth-century Kinneddar.

The Kinneddar site is landlocked now, but in the early Middle Ages it lay on the shore of Loch Spynie, which opened to the sea at what is now Lossiemouth. This gave it a natural harbour and easy access to the Moray Firth.

In fact all four northern ‘David’ sites are located at or near harbours on the Moray Firth, Cromarty Firth and Dornoch Firth. If they were all sites on a royal circuit, it’s highly conceivable that the royal entourage travelled between them by boat.

Kinneddar absolutely fits the profile of a royal itineration site, except for one thing. It’s only eight miles from Burghead, which I see as the secular ‘capital’ of eighth-century Moreb. As such, it would have drawn on the same scarce agricultural land and resources as both Burghead and the poorly-understood early medieval settlement on Clarkly Hill.

A decampment from Burghead to Kinneddar therefore may not make sense from a survival point of view. Instead, these three sites together (perhaps with others on the Duffus ridge not yet recognised) may have acted together as a kind of ‘polyfocal central place,’ like the one identified by the Northern Picts Project at Rhynie in Aberdeenshire—albeit from a slightly later period. The relationship between these three sites hasn’t yet been investigated, so I’ll put it on my to-do list.

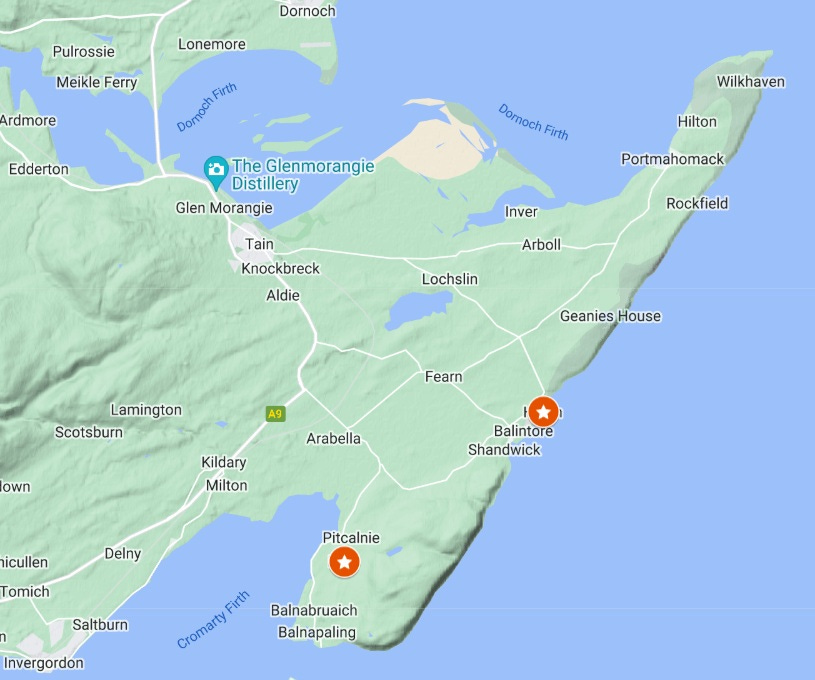

2. Nigg

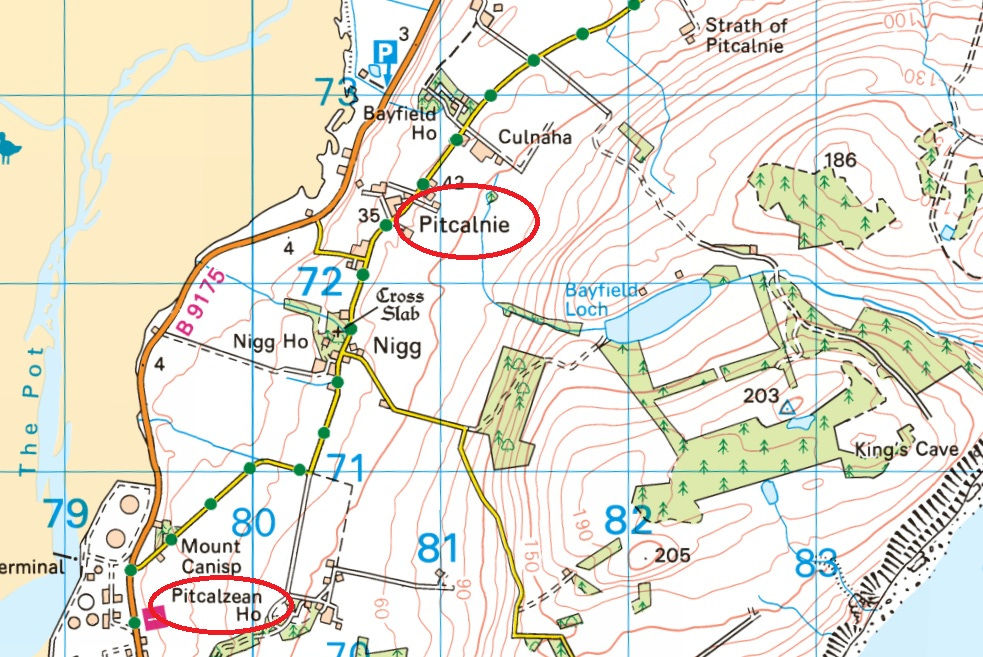

The magnificent cross-slab at Nigg was first recorded in the late eighteenth century in the kirkyard at Nigg Old Church, and is now inside the church.

The church stands beside a stream on rising ground overlooking the Cromarty Firth, although today the view seems to be obscured by trees. (I don’t know this area personally, so I’m relying on Google Streetview.)

A clue to its early medieval status may be preserved in the fact that the stone is located at the parish church. In his book Land Assessment and Lordship in Medieval Northern Scotland, Alasdair Ross noted that Nigg parish remains unchanged from its original medieval extent, encompassing the southern portion of the Tarbat peninsula.

In his 1992 PhD thesis, John Rogers argued that parishes were established in Scotland in the twelfth century at such a rapid pace that they must have been based on pre-existing territorial units. He proposed that these units were early medieval ‘multiple estates’—royal or aristocratic landholdings comprising:

…a principal settlement or caput with a number of dependent settlements.

Although there are no documentary sources for Nigg prior to 1255, its layout and place-names do suggest that it may been such a multiple estate. Nigg House, the residence of the laird of Nigg, adjoins the kirkyard, forming what looks very much like the caput of a secular estate. (The current house dates from 1702, but the site itself may well be centuries older.)

To the north and south of this proposed caput are two areas whose names begin with Pit: Pitcalnie and Pitcalzean. Although the suffixes here are Gaelic, the prefix ‘pit’ is generally considered to derive from an original Pictish word pett, meaning a portion of (productive) land.

So even a cursory look at Nigg offers hints that in the early Middle Ages it was an elite estate, centred on the church and presumed lordly residence, with dependent settlements and land at Pitcalnie and Pitcalzean. There could hardly be a better candidate for the type of wealthy, secular landholding that might have hosted a king and his retinue on a royal circuit of Moreb.

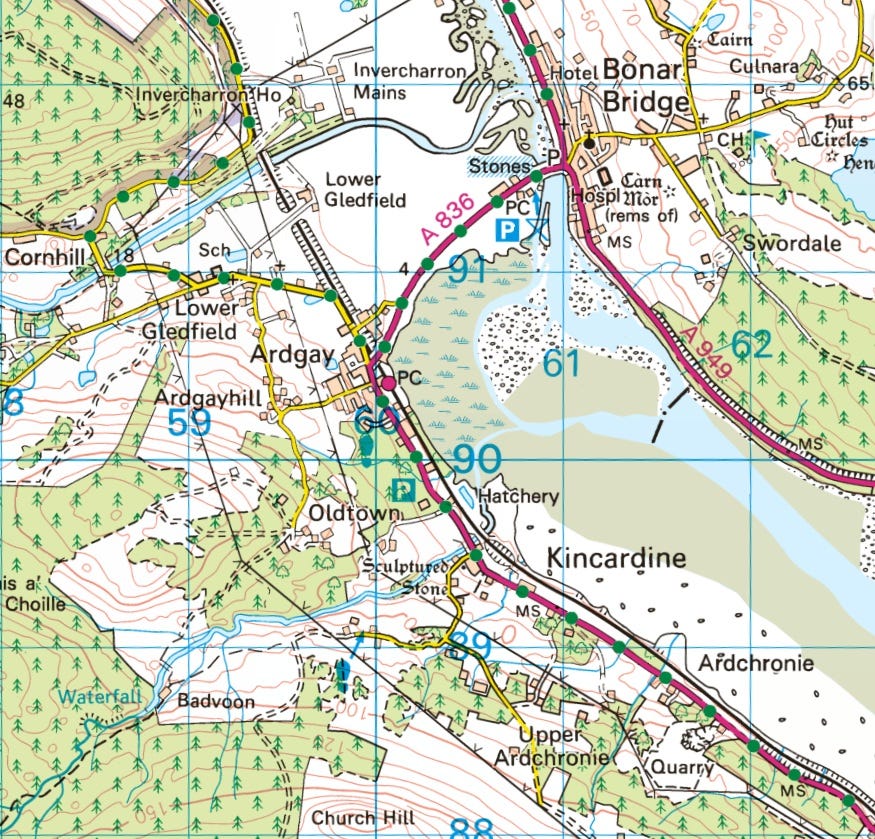

3. Kincardine

Kincardine lies on the southern shore of the Dornoch Firth near Bonar Bridge, where it narrows to become the Kyle of Sutherland. It also sits at the firth’s tidal limit, making it the farthest place in Easter Ross that’s easily reachable by boat from Burghead.

The monument in question here is an unusual one: a horizontal slab into which two hollows have been carved, forming it into a kind of stone trough. However, Jane Geddes, among others, argues that these hollows may be later additions, with the original piece functioning as a recumbent grave-marker: a slab that lay over a grave rather than standing at the head of it.

Either way, the Kincardine monument not only has an image of David rending the lion’s jaws and accompanied by a floating harp, but also has a panel with a lone horseman riding to the hunt, a trope which Donald Bullough identified as also emblematic of early medieval kingship.

Other than this, it’s hard to identify what kind of ‘place’ Kincardine might have been in the eighth century. Certainly, as at Nigg, the monument is located at the old parish church, which sits beside a stream and overlooks the Dornoch Firth and the hills of Sutherland to the north-west.

The immediate environs of the church are arable land, again as at Nigg, but otherwise Kincardine is a wilderness parish, stretching deep into narrow highland straths, with the church located on its coastal fringe. There’s no obvious ‘big house,’ nor any ‘pett’ place-names or other place-names to suggest there was a royal or aristocratic estate here in the later first millennium.

Then there’s the difficulty of explaining the nature of the ‘David’ monument. As a recumbent, it would have covered a grave, but it’s hard to imagine a royal personage being buried here, far from the centre of the kingdom at Burghead. The David imagery is also on the side of the slab, rather than the top, where whatever carving once existed has completely worn away.

So the verdict on Kincardine is inconclusive. Its high-quality David sculpture implies a royal connection, and it’s easily reachable by sea, especially when sailing with the tide. But as to whether its lands and resources could sustain lengthy visits by the king and his household, I couldn’t currently say. Another one for future investigation!

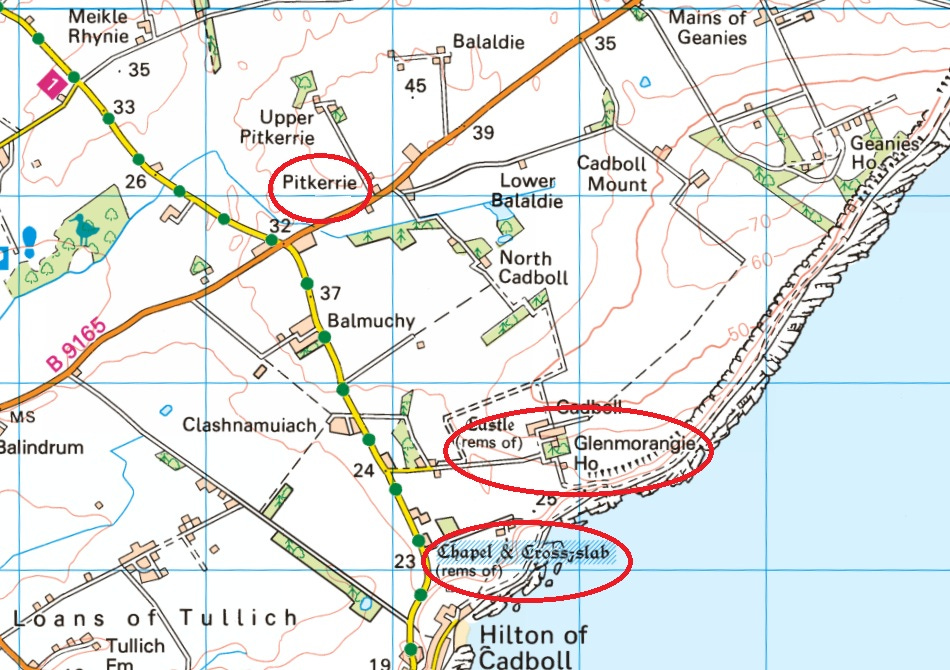

4. Hilton of Cadboll

The fourth and final site is Hilton of Cadboll, on the Tarbat peninsula.

This is the site of a famous and well-studied Pictish symbol-bearing cross-slab, whose original is now in the National Museum of Scotland, with a replica standing on the site.

Although David doesn’t appear on this stone, Isabel Henderson saw it as belonging to the David family of monuments owing to its similarities to the Canterbury Vespasian Psalter of c. 725:

The close resemblance of the Hilton of Cadboll trumpeters to the trumpeters in the David and his Musicians miniature in the Vespasian Psalter, and the fact that musician imagery is found with other David iconography on the Nigg cross-slab, suggest that the figures must have been taken from a model available in Easter Ross showing the courtly scene of David surrounded by his musicians.

(Although personally I think that the pair of trumpeters depicted on Trajan’s Column, as pointed out by Helen McKay in this blog, are a closer match.)

The Cadboll stone differs from Nigg and Kincardine in another important respect. The most prominent rider shown on the stone is generally agreed to be a woman. She has her cloak fastened with a central penannular brooch in a manner known to have been used by women, and is ‘labelled’ with a mirror and comb, generally considered to be markers of female gender.

There is some debate as to who she is meant to be, with a local noblewoman, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the Celtic horse goddess Epona all regularly cited. In her recent paper, Jane Geddes proposed that she is a ‘Pictish aristocrat taking part in the royal hunt,’ in line with her (Jane’s) conception of the peninsula as an eighth-century, Carolingian-style royal hunting ground.

I must confess to some scepticism here. Unlike Carolingian Francia, cultivable land was very scarce in the early medieval Moray Firthlands, found mostly along the coastal strips. Since subsistence and wealth stemmed from the land, it seems unlikely that the fertile peninsula would have been given over to hunting. To my mind, the wilder landscapes of Strathspey, Glenferness or the hinterland of Kincardine would have been better suited to this purpose.

A landing-place for a queen?

However, I do find Jane’s notion of Cadboll as a landing-place for a queen compelling. When I was reading Thomas Charles-Edwards’s chapter on royal itineration, I was struck by this note:

Though this model [of the royal circuit] is helpful, it is oversimplified, since it suggests that there was only one royal household which went on circuit. For seventh-century Northumbria, at least, this assumption is false. [T]here is clear evidence that the queen sometimes had a separate household from the king.

He goes on to give the example of Eanfled, wife of the Northumbrian king Oswiu (d. 670), who appears to have lived in a different place and kept different customs from the king.

Could Cadboll have been an estate on the queen’s circuit, rather than the king’s? Like Nigg, it has a ‘big house,’ once a castle but now a hotel owned by the Glenmorangie distillery. It also has an outlying ‘Pit’ place at Pitkerrie, perhaps a ‘dependent settlement’ in Rogers’s model of the early medieval multiple estate.

Cadboll never had a parish church—it’s in the medieval parish of Tarbat, with its church at Portmahomack—but it does have a chapel site with persistently female connections, and which is generally considered to have been the stone’s original location.

In his 1904 book Place-Names of Ross and Cromarty, W.J. Watson identified nine female-coded place-names in the vicinity of the chapel that had come and gone over time:

At Hilton of Cadboll stood a chapel dedicated to the Virgin ‘Our Ladyis Chapell’ 1610, in connection with which appears in 1610 Litill Kilmure, Toil of Kilmuir, a well called Oure-Lady-well…also the heavin called Our-Lady-heavin of Kilmure… Creag na baintighearna, Lady’s Rock, is under Cadboll; Tobar na baintighearna, Lady’s Well, is (or was) near a small graveyard east of Hilton; Port na baintighearna, Lady’s Haven. The name Kilmuir seems to have gone, but there is Bàrd Mhoire, Mary’s meadow or enclosure.

While some of these names inarguably reference the Virgin Mary, those with the Gaelic word baintighearna are less obviously associated with the BVM. Bantighearna means a noblewoman, the “wife of a baronet or knight,’ according to Dwelly’s online Gaelic dictionary. Indeed Watson noted that:

I have met no other clear instance of bantighearna in the sense of Our Lady.

It’s notable that these natural features—a rock, a well, and a landing-place—are independent of the chapel. Is it possible that the dedication of the chapel to the BVM was made later, inspired by these place-names and the image of the lady on the cross-slab?1 And that the names of these features preserve a memory of an older tradition—that eighth-century queens of Moreb regularly visited, or even directly owned, the estate of Cadboll?

Conclusion: Possible, but more work needed

I haven’t come away from this investigation with a clear yes or no to my question: Do the ‘David’ monuments in the Moray Firthlands preserve a vestige of an eighth-century royal circuit?

But having looked in brief at the four sites in question, I’m not yet ready to rule it out. I still think there’s something in the idea, but the sites need much deeper examination.

I also didn’t have room here to look at two other sites that I think could also have been stops on a royal iter: the monastery at Portmahomack and a possible second monastery at Edderton near Tain. It’s definitely an idea I’ll come back to as I continue my research. In the meantime, if you have any thoughts, I’d be delighted to hear them.

References

Bernhardt, John W. Itinerant Kingship and Royal Monasteries in Early Medieval Germany, c.936-1075 (1993)

Bullough, Donald. ‘Imagines regum and their significance in the early medieval West.’ In Studies in Memory of David Talbot Rice, edited by Giles Robertson and George Henderson (1975)

Charles-Edwards, Thomas. ‘Early medieval kingships in the British Isles.’ In The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms, edited by Steven Bassett (1989)

Geddes, Jane. ‘What is “David” iconography doing in Pictland?’ Conference paper, Pictish Arts Society annual conference (2024)

Henderson, Isabel. ‘The “David Cycle” in Pictish art.’ In Early Medieval Sculpture in Britain, edited by John Higgitt (1986)

James, Heather F. ‘Pictish Cross-Slabs: An Examination of Their Original Archaeological Context,’ in Able Minds and Practised Hands: Scotland’s Early Medieval Sculpture in the 21st Century (2005)

James, Heather F., Isabel Henderson, Sally M. Foster, and Siân Jones. A Fragmented Masterpiece: Recovering the Biography of the Hilton of Cadboll Pictish Cross-Slab (2021)

McKay, Helen. ‘Pictish Women and the Mirror and Comb.’ Substack blog (2024)

Noble, Gordon, Gemma Cruickshanks, Lindsay Dunbar, et al. ‘Kinneddar: a major ecclesiastical centre of the Picts.’ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 148: 113–145 (2019)

Rogers, John. ‘Formation of the parish unit and community in Perthshire.’ PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh (1992)

Ross, Alasdair. Land Assessment and Lordship in Medieval Northern Scotland (2015)

Stratigos, Michael. ‘A Model of Coastal Wetland Palaeogeography and Archaeological Narratives: Loch Spynie, Northern Scotland.’ Journal of Wetland Archaeology 20 (1–2): 43–58 (2021)

Watson, W.J. Place-Names of Ross and Cromarty (1904)

Woolf, Alex. From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070 (2007)

UPDATE 1.1.25 Having looked further into this, this feels like a plausible scenario. Excavations around the site of the cross-slab revealed two settings for the stone, one dating to the mid-12th century, and one earlier. The technique used was Optically Stimulated Luminescence, which gives a fairly accurate date range. It was the opinion of Heather James that the second, later, setting may be related to the building of the chapel: “The medieval chapel was dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and there may be a connection here with the female hunting scene depicted on the back face of the cross. Both of the settings are several degrees off being parallel with the chapel wall. Perhaps the earlier setting was aligned with another feature in the landscape, and this alignment was retained when the cross was re-erected despite the addition of the chapel into the landscape.” Heather F. James, ‘Pictish Cross-Slabs: An Examination of Their Original Archaeological Context,’ in Able Minds and Practised Hands: Scotland’s Early Medieval Sculpture in the 21st Century, edited by Sally M Foster and Morag Cross, paperback edition (Routledge, 2020), 101.

Another intriguing and well argued idea Fiona.

Couple of thoughts:

Remember Kincardine, or at least the carden element, is also a Pictish word, meaning woodland. So maybe a king would visit to go hunting at the “head of the woods. If its primary purpose was for the hunt there would not necessarily need to be an estate to provide sustenance for a longer stay

Also, if you are taking the David iconography as the marker for such stopping off points on a royal itinerary, where does Forres fit in if Jane’s identification of the inauguration scene as based on David is correct?

On an unrelated topic, are you enjoying Only Child and its Forres setting? The final episode particularly with a good Forres worthy speaking what can only be modern Pictish! 🤓

Many thanks for sharing your research, which is fascinating reading. I became aware of the royal practice of itineration through study of Northumbrian kings of the 7th century, for which there are diverse and surprisingly plentiful sources. Recently I re-read Max Adams's "The King in the North, the life and times of Oswald of Northumbria" (2013), which despite the Game of Thrones reference in the title is actually a very fascinating and close study of royal practices and of how land was exploited in that period. I'd recommend it to anyone struggling to understand how these systems work. Of course, Northumbria isn't Pictland, but it would be a surprise to me at least if there wasn't a similar system employed in the real north!