Auldearn: A place-name mystery revisited

In which I take a new look at this puzzling place-name, and come to an unexpected conclusion.

Hello! I’m back after a very long break from this Substack, during which I researched, wrote and submitted my MA dissertation. So the MA is now all done, and I’m just awaiting my final grade.

Thrillingly, I’ve been accepted to do a PhD at the University of Glasgow, with the brilliant Professor Katherine Forsyth as my supervisor—starting this coming week! I’m still pinching myself, as this isn’t something I could even have dreamed of doing even four years ago.

My focus is going to be on uncovering the early medieval history of the tiny county of Nairnshire on the Moray Firth, an almost entirely neglected area in terms of Pictish and Viking-Age studies. I have so many ideas and I can’t wait to get stuck in.

A return to Auldearn

So, fittingly, this first Substack of the post-MA era is about a place in Nairnshire with a hard-to-explain place-name: Auldearn. When I started writing this post I had a couple of ideas that I wanted to test out, but as I began to look into it, they quickly turned out to be misguided.

Instead, I found something potentially much more interesting: lingering evidence in place-names of the ‘Anglo-Norman’ conquest and colonisation of the province of Moray (which included Nairnshire) in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The central Middle Ages aren’t really my period (although it’s impossible to study the early Middle Ages without some appreciation of what came afterwards), so please do correct me on anything I get wrong here.

The Anglo-Norman castle of ‘Eren’

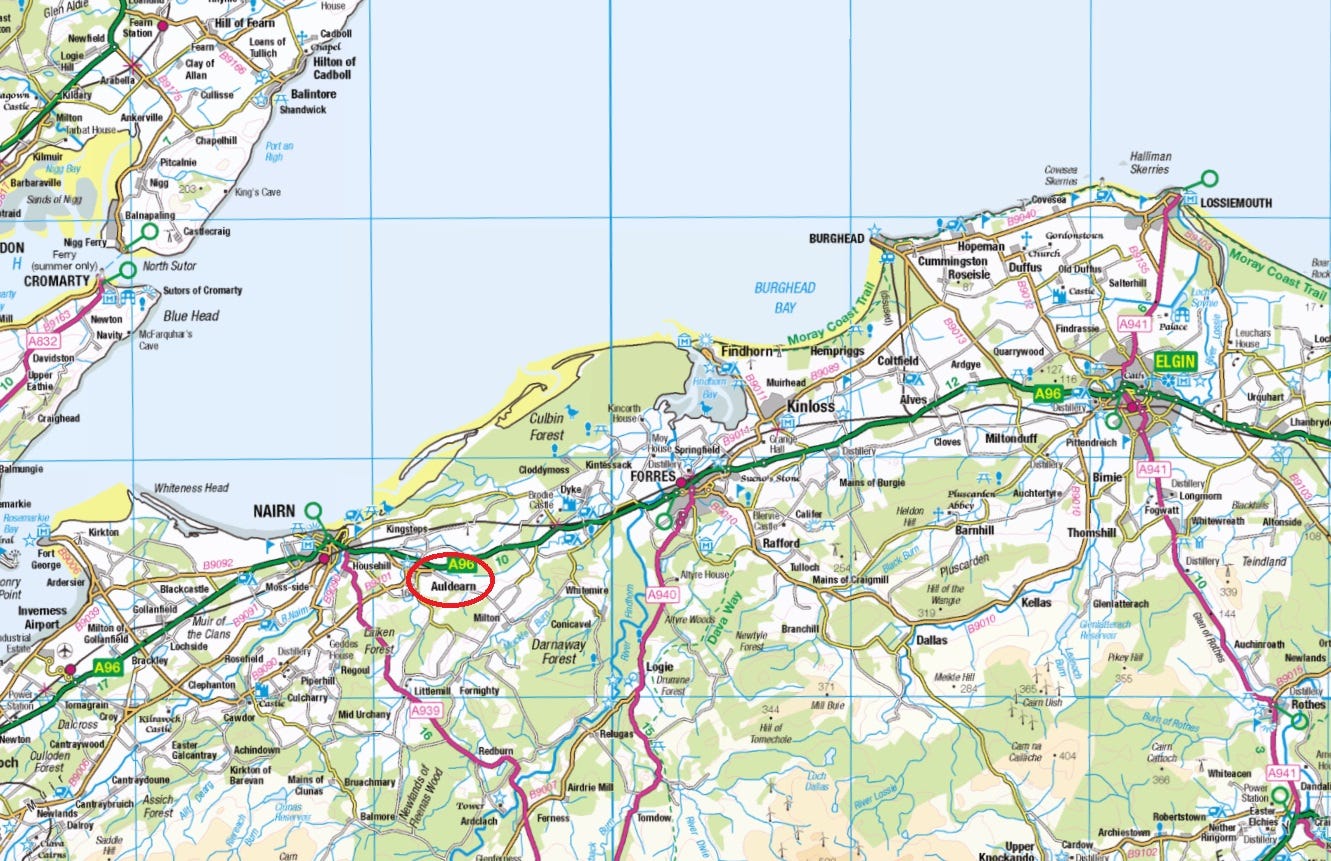

I’ve written about Auldearn (circled below) in some detail before. It’s a village just to the southeast of Nairn with a particularly turbulent history. In 1187, it was the place where the castle of the ‘Anglo-Norman’ king William I of Scots (William the Lion, r. 1165–1214) was ‘betrayed’ to the king’s local opponents by one Gillecolm.

Prior to this betrayal, William drew up a couple of charters at his castle of Auldearn: one sometime between 1173 and 1190, and the other sometime between 1179 and 1182.

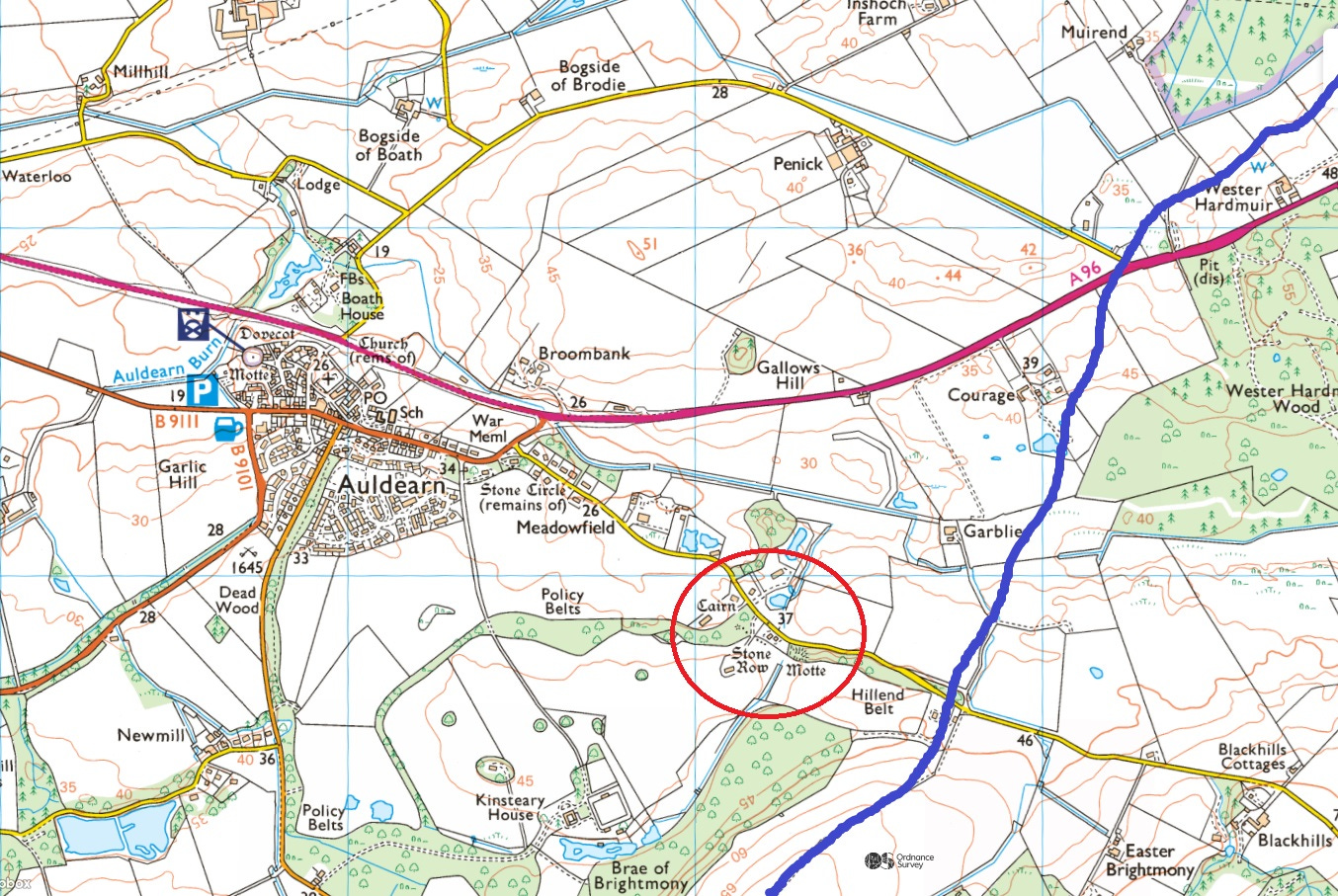

In those charters, the name of the castle is given as ‘Eren,’ not Auldearn. But it seems certain that Auldearn is the place meant. Apart from the similarity of the ‘earn’ part of the name to ‘Eren,’ the Dooket Hill on the edge of the village has the appearance of a Norman-style motte (below), and ‘Eren’ is listed between Inverness and Forres in early charters, implying that it lay between the two.

A confusing place-name with ‘Irish’ overtones

This name ‘Eren’ has puzzled place-name specialists for at least a century, for three reasons. Firstly, ‘Eren’ also seems to have been the medieval name of the River Findhorn, which appears in two twelfth-century charters of Kinloss Abbey as aqua de Eren. But Auldearn isn’t on or even particularly near the Findhorn—in fact the burn that runs past it is a tributary of the River Nairn.

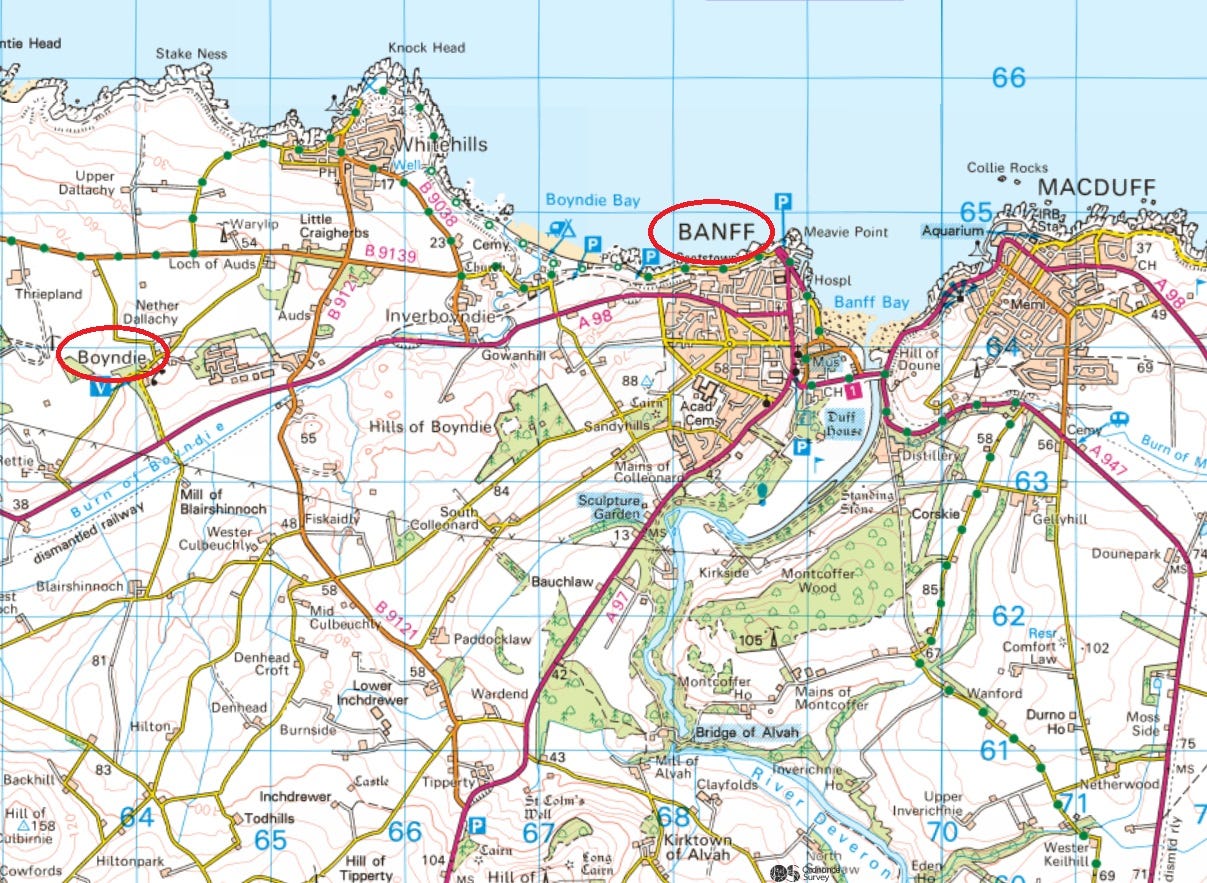

Secondly, it’s one of an oddly large number of places along the Moray Firth littoral whose names seem to contain references to Irish mythology. In 1926 the toponymist W.J. Watson identified four places that seem to be named after patron goddesses of Ireland: Boyndie (after Bóanda), Banff (after Banba), Elgin (after Ealga), and Eren (after Ériu). He also suggested that Dunphail, just south of Forres, is named after Fál, the mythical city that gave its name to the Lia Fáil, the Stone of Destiny.

Thirdly, ‘Eren’ last appears as the name for Auldearn in a charter of c.1242. When it next appears, in a charter of 1362, its name is now ‘Aldheryn.’ This prefix ‘Ald’ has prompted some debate. Watson saw it as Gaelic allt, a stream or burn, and proposed that the whole name is allt-Eireann, or ‘Ireland’s burn.’ In a 2010 article Thomas Owen Clancy questioned this, pointing out that:

Although Watson and others have taken this to be from G. allt ‘stream’ + Eren, the early forms of the name are somewhat less convincing in this respect, lacking as they do the crucial postulated generic.

In other words, the older name ‘Eren’ makes no reference to a burn. By Watson’s logic, this would make the original name just mean ‘Ireland’s,’ which makes no sense.

Instead, given that the name ‘Aldheryn’ only appears in the fourteenth century, when coastal parts of Moray and Nairnshire would have been largely Scots-speaking, Clancy proposed that the prefix is actually Scots ‘auld’ for ‘old’, and that the name means ‘Old Eren.’ But there’s no sign of a ‘New Eren’ against which Auldearn might need to be contrasted.

Other than the apparent lack of a ‘New Eren,’ Clancy’s argument seems solid, and it trashes one of the ideas I’d been planning to try out with this post. I’m going to post it anyway, though, just to show that historical research is full of dead-ends and failed hypotheses.

The ‘boundary stone of Eren’?

I’d long been mulling the idea that ‘Eren,’ as well as apparently being the original name of the River Findhorn, was also an early name for the whole of the lower Findhorn basin.

I was swayed in this by the name ‘Earnside,’ a fourteenth-century castle that lay within the catchment of the Findhorn but several miles from the actual river, and by a place that in the thirteenth century was called ‘Ulern’ or ‘Vlerin,’ which also seemed to me to contain the Earn/Eren element. This place is Blervie, southeast of Forres, and is also not on the Findhorn.

Then, in trying to make sense of the name ‘Aldheryn,’ it appeared to me that the eastern end of Auldearn could just about be said to sit on the watershed between the rivers Nairn and Findhorn, and thus just about on the boundary of the area I’d been thinking of as ‘Eren’.

In seeking possible meanings for the ‘Ald’ element, I alighted on the Old Irish (or Pictish) word ail or alo, generally meaning a rock or stone. It appears most notably in the name of the British kingdom of Alt Clut, meaning ‘rock of the Clyde,’ referring to its caput at Dumbarton Rock.

From eDil, the online dictionary of historical Irish, I learned that one of the many meanings of ail is a boundary stone. It didn’t take too much for my brain to decide that ‘Aldheryn’ could be al[t]-eren, the boundary stone of Eren.

I was fondly imagining that the ‘boundary stone’ in question might be the Bronze Age cairn and/or stone row at Kinsteary (circled in red above, with the watershed/boundary in blue), when it dawned on me that this was all nonsense.

If Auldearn really was named after an ancient stone on an ancient boundary of an ancient district of Eren, it would have been called Auldearn all along, not just from 1362 onwards.

Sometimes you have to let your pet theories go, no matter how satisfying they may seem.

What is the meaning of ‘Eren’?

So Clancy was surely right and Auldearn is ‘Old Eren.’ But what was meant by ‘Eren’? Here, Clancy tentatively agreed with Watson that the name was intended to evoke Ériu, a patron goddess of Ireland:

There is considerable evidence of widespread use of the term Eren in Moray and it is difficult to completely explain this by recourse to hydronyms; one significant site, Auldearn, cannot be explained this way. On balance, we may feel justified in cautiously supporting the view that the name of Ireland was being employed.

He also noted that along with Banff and Elgin, ‘Eren’ was a castle and burgh founded in the twelfth century by the kings of Scots in a bid to bring the province of Moray under their direct control.

It is striking that at the very earliest stratum of detailed place-name record, in the twelfth century, we find the names Eren, Elgin and Banff appearing as already central places on the way to development as burghs, often in the same charters. They were major building blocks in the Scottish kings’ policies in the North-East.

Clancy’s proposal, articulated very subtly, was that all three places were given their ‘Ireland’ names during this period of colonial castle- and burgh-building:

If Eren, Elgin, and Banff are coinages of this sort, it may be thought they belong to a particular moment in the settlement history of the North-East, one in which an appreciation of the pseudohistory and the poetic naming of Ireland was present, and one when the Irish identity of the Scottish kingship was to the fore. Given their status as central places during the twelfth-century conquest of Moray, it may be that that moment was not very far distant from it.

Citing research by Dauvit Broun, he noted that David I (r. 1124–1153), and the men of letters who surrounded him, were concerned to give the kingship of the Scots a conspicuously Irish identity and pedigree, and may therefore be the likeliest suspects behind the spate of ‘Ireland’ names:

We may wish to think in particular of the reign of David I, a reign which saw consolidation of power in the North-East at a time when the Scottish kingship’s pseudo-historical Irish identity was being embraced.

In other words, the naming of some of the newly-founded Moray burghs after Irish deities may have been part of an effort to stamp a particularly ‘Irish’ brand of royal authority on the region.

I have to say that, if this is the case, it’s not clear to me what exactly these names were meant to signify, and to whom. I need to have a proper read of Dauvit Broun’s famously difficult 1999 book The Irish Identity of the Kingdom of the Scots before trying to grasp the significance.

The evidence of the Findhorn and Deveron

One thing I will add, though, is that William the Lion or Alexander II (r. 1214–1249) are perhaps likelier suspects than David I for this spate of Ireland-themed re-naming. For a start, William seems to have spent a lot more time in Moray than David I, who only took direct control of the province very late in his reign, after 1147.1

And suspiciously, it seems like the River Findhorn may have acquired that name during William’s or Alexander’s reign. It appears as aqua de Eren in two charters of William dated to 1187, but these are confirmation charters of grants made in 1150 by David I and may reflect the naming of that earlier time. However, in a charter of 1226, it appears for the first time as aqua de Fyndaryn, the ‘water of the white Earn.’

This suggests that sometime between 1150 and 1226, someone saw fit to rename the Earn, in Gaelic, as the ‘White Earn.’ The reason, as Watson, Clancy and others have pointed out, was surely to contrast it with the other northern Earn, the river now called the Deveron or ‘Black Earn’. And it’s at the mouth of the Deveron that we find the other apparently Irish mythology-inspired names Banff (after Banba) and Boyndie (after Bóanda) - see map below.

Taken together, all of these names suggest a determined late twelfth- or early thirteenth-century effort at colonising the northeast by a military power with its sights set on the entire Moray Firth littoral. Readers more familiar with twelfth-and thirteenth-century Scotland than I may be able to suggest whether William or Alexander (or neither!) might be the likelier suspect here.

What was Auldearn called before the twelfth century?

If this theory is correct, these new names must have over-written or displaced existing names for these places: a textbook act of colonialism.

In the case of Auldearn, people had lived on the spot for millennia. The cairn and stone row mentioned above suggest it was a centre of some significance in the Bronze Age, and some fine Iron Age metalwork (reported on p. 6 here) and a possible souterrain, now under a housing estate, suggest it remained so in the Iron Age.

There are strong indications that Auldearn was also an important place in the early medieval period. Its church sits close to an apparently-artificial mound; indeed the mound that seems to have been commandeered by David for the castle motte of ‘Eren’.

This reflects a common early medieval arrangement in which a church was established next to a moot hill or court hill. A celebrated example is Govan Old Church and the now-lost Doomster Hill in Glasgow (below).

Another sign that Auldearn church had early medieval origins are the hints (which I wrote about here) that it once housed an iron hand-bell of the period 700–900 AD. Indeed, since Auldearn parish is dedicated to Columba, the bell may actually have been brought from Iona as part of a mission (not by Columba himself, but later in the first millennium), and may have been considered a relic of the saint.

In this case, we may still be able to see the name that ‘Eren’ displaced. The estate of Boath, once part of Auldearn but now separated from it by the A96, may preserve a Pictish word, both. Its core meaning is house or hut, but Simon Taylor noted in 1996 that in Eastern Scotland it had ecclesiastical associations, since it appears in numerous parish names.

So perhaps before Auldearn was Eren, the castle of Ériu, it was Both, the place of the church. (Although technically one might expect there to be some qualifier after the both: Taylor cites Bothmernock in Angus as the ‘church of St Ernoc.’)

It’s worth noting that if this were the case (and I am layering speculation on speculation; never very advisable), ‘Both’ would also have displaced an even older name; the name used perhaps by the people who dug the souterrain, or even the people who built the stone row and burial cairn. Whatever name or names they knew Auldearn by seem lost to us now, unless any palaeolinguists can spot them in any of the surrounding place-names.

But what of the ‘Auld’ prefix?

The process by which ‘Eren’ came to be known as ‘Old Eren’ remains a mystery. It’s true that the castle of Auldearn seems to have been abandoned after the betrayal of 1187, and a replacement built at Nairn. But Nairn doesn’t mean ‘New Eren’—it’s named after the River Nairn, “in all probability” an ancient early Celtic name, according to W.F.H. Nicolaisen.

We can also see from charters that Auldearn is still called ‘Eren’ around 1242, long after the establishment of the castle and burgh at Nairn. It also hung on to its church, which by this point was the centre of an unusually large medieval parish. This suggests that Auldearn wasn’t abandoned in any meaningful way, and that it continued to be a place of substance.

Clancy suggested that it might have been given its ‘Auld’ prefix to distinguish it from “the now-lost Invereren, at the mouth of the Findhorn.” Indeed, a terram de Invereren appears in a protection charter of c.1187 as one of the lands granted to Kinloss Abbey by William the Lion.

However, the same charter records that William also gave the monks of Kinloss unum toftum in Eren—a burgage plot in Auldearn. It seems clear from this charter that both Eren and Invereren were in existence at the same time, and that while Eren was a burgh, Invereren was a portion of agricultural land. So it’s hard to see how ‘Invereren’ could have been a successor to ‘Eren.’

A lost port of Eren?

One possibility that occurred to me was that ‘New Eren’ could have been a port at the mouth of the Findhorn, just as the village of Findhorn is today.

The topography of the Findhorn estuary has changed massively over the centuries, due to a combination of a westward longshore drift that builds up sandbars, and occasional violent storm spates that alter the course of the Findhorn.

Indeed the current village of Findhorn replaced an earlier village that was submerged c.1700 when the river in spate punched a new, more direct, course for itself into the Moray Firth. A fascinating map from 1758 (below) shows that before this, the mouth of the river was further west.

It’s just possible to imagine that the river once emptied into the Firth much farther to the west, perhaps just north of Auldearn. The local historian George Bain was certainly convinced that this was the case, writing in his 1893 History of Nairnshire that:

Anciently the Findhorn ran much further west than it does at present. The Old Bar within four miles of Nairn marks its channel and outflow at one time. The great sand-drift has changed the course of the river, and greatly altered this part of the coast. A deep channel extends for some distance along the inner side of the outer extremity of the Old Bar, and still has a depth of water of six or eight feet at ebb tide, when the sands all around are bare. This strype, as it is called, probably marks the old mouth of the river.

Since the river itself was called Eren, it’s possible to imagine that a port at its old mouth might also have been called Eren, just as Findhorn is at the mouth of the Findhorn today.

But this theory doesn’t work. For this port to be the ‘New Eren,’ it would have to have been built after the castle of ‘Old Eren’ at Auldearn had been abandoned, so after 1187. And while there is evidence of a later twelfth-century port north of Auldearn, it’s not called ‘Eren’ but Lochloy.

In Roger of Hoveden’s Chronica, completed around 1200, he records a meeting in 1196 between William the Lion and Earl Harald Maddadsson of Orkney, at which the earl was supposed to hand over some of William’s enemies to the king (which he failed to do).

Roger says that:

..in autumno rediit rex Scottorum in Murreviam usque ad Ilvernarran, ut reciperet ab Haroldo inimicos suos; quos cum Haroldus produxisset usque ad portum de Locloy prope Dilvernarran…

…in the autumn the king of Scots [William] returned to Moray, as far as Nairn, in order to receive his enemies, whom Harald was supposed to have brought to the port of Lochloy near Nairn…

Lochloy (or at least the modern house of Lochloy) is circled on the map below.

Additionally, no port of Eren appears in any medieval charter for the region. Whenever the name ‘Eren’ appears, it only refers to the river or to Auldearn. So that idea is a bit of a non-starter.

The ‘old castle of Eren’?

The other possible explanation is that if Auldearn continued to be a settlement, church and parish throughout the Middle Ages, perhaps the only thing ‘old’ about it in 1362 was its long-abandoned castle.

Though I have virtually no knowledge of fourteenth-century Moray, I wonder if the name-change occurred after Robert the Bruce granted the entire province out to its first Earl, Thomas Randolph, in 1312.

Did the establishment of this new mode of lordship make vestiges of direct, colonial rule by the Canmore kings seem suddenly ancient, part of a different era? In which case ‘Aldheryn’ may just have been shorthand for “the old castle of Eren,” and we needn’t look for a New Eren at all.

Conclusion: Time to rethink the Gaelicisation of Moray?

As long-time readers will know, I research these blogs as I write, never knowing at the start where I’m going to end up.

With this one, I ended up in a very different place from the one I expected. I really thought I was going to demonstrate that the name ‘Auldearn’ derives from an ancient Pictish name meaning ‘boundary stone of Eren,’ and that it would prove that there was a district called ‘Eren’ in the early Middle Ages that encompassed the whole of the lower Findhorn drainage basin.

Instead, having re-read (and researched around) Thomas Clancy’s critique of Watson’s theory about the name Auldearn, I’ve ended up convinced that Auldearn got its name of ‘Eren’ as part of a colonialist renaming strategy by the twelfth or thirteenth-century kings of Scots.

If correct, this has quite major ramifications for our understanding of the Gaelicisation of Moray, since some of these ‘Ireland’ names have been seen as evidence of a first wave of Gaelic settlement in the early medieval period.

If they actually belong to the central Middle Ages, we might want to think again about when and how Moray was Gaelicised. But that is definitely a topic for another time!

References

Bain, George. History of Nairnshire (1893)

Broun, Dauvit. The Irish Identity of the Kingdom of the Scots in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries (1999)

Clancy, Thomas Owen. ‘Atholl, Banff, Earn and Elgin: 'New Irelands' in the East Revisited’ (2010)

Innes, Cosmo (ed.) Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis (1837)

Nicolaisen, W.F.H. Scottish Place-Names: Their Study and Significance (1986)

Stuart, John (ed.) Records of the Monastery of Kinloss (1872)

Stubbs, William (ed.) Roger of Hoveden, Chronica, vol. 4 (1868)

Taylor, Simon. ‘Place-Names and the Early Church in Eastern Scotland,’ in Scotland in Dark-Age Britain, edited by Barbara Crawford (1996)

Watson, W.J. The History of the Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (1926)

UPDATE: No, scratch that, David is also implicated in the re-naming. As Watson points out, a charter of his from around 1140 grants the monks of Urquhart Priory the land of Pethnec iuxta Erin (Penick near Eren), showing that the name was already in use by that year.

A very thought-provoking blog Fiona - and let's hope your PhD work turns up more of the same!

That’s interesting finding ‘Eren’ as the name of a Norman castle perhaps. But, my concern would be that this doesn’t mean that all the other names across this inner Moray coast are of the same period. In fact, I’d really doubt it. It’s more likely that the Normans either mashed an original name, or just gave their castle what they thought was an important name locally.

I’ve gone round and round in my head about these ‘Irish’ names in the region, but so far without hitting on a solid solution. First, if later people were trying to ‘Irishify’ the region, or if early Irish were (re-)naming places for their own goddesses, then they wouldn’t just use Eriu and Banba without the third Fodla. It just wouldn’t happen. All over the Celtic lands the mother/land goddess comes in a triplicate. As for Ealga, without modern encyclopedias and wikipedias I would seriously doubt how many people would even know of her ‘Irish’ existence, the name is so rare and peculiar. Then we also have Ness, the loch and river attested at least by Adomnan, who is the mother of the Ulster king Conchubar, Caren (IIRR) who is the mother of Niall of the Hostages, and Boand>Boann who is attested on the continent, then men, Taranis, Brendan, Brannan, Nectan – and that’s just off the top of my head, there’s probably as many again. Even the river Nairn is suspicious, modern Narann, although WP says it may originally be *Naverna, but Nar is a name I’ve seen at least twice in Irish texts. The main problem here is that these are Celtic deities/heroes/ancestors, most of them are pan-Celtic, so it may not be that this region is being renamed at all, it’s just that the names here have stuck. And there are plenty of other instances all over Pictland with so-called ‘Irish’ deity names too, the prevalence of which suggest pan-Celtic names rather than ‘Irish’.

Alternatively, it could betray a significant western immigration pattern followed by renaming. But then the question is ‘when’? (No.1 Pictish mantra – Its all about the dating!). For me, I suspect that this happened during the later Roman period, because the archaeology tends to show this region as different from the rest of Pictland, and that may be the case right up until the 700s (and yes I do include Burghead here). The region shows a coastal strip without any CI stones that I can happily date to after 200 AD. And the CI (ie pagan) stones sit in an outer ring around this void Moray coastal region, void until it gets quite late CII stones. From 200 – 700 AD is half a millenium – a looong time for lots of things to happen. This whole period is such a ‘dark age’.

You might want to read G.R. Isaac, “A note on the name of Ireland in Irish and Welsh”, Ériu 59 (2009): 49-55. It supports what Nicolaisen wrote about the river names in his 1993 article.