Did three early kings of Scotland die in Forres?

Once is happenstance, twice is coincidence, three times is... evidence of an early royal centre?

In my last blog I said that, because there are so few reliable written sources, you have to deduce the early medieval history of Scotland in other ways: from place-names, archaeology, and so on.

I may have given the impression that there are no written sources, but that’s not quite true. There are a handful of later medieval manuscripts that are undoubtedly copies of manuscripts written in the first millennium AD. Together, they provide tiny – and tantalising – scraps of information about what went on in Scotland prior to 1000.

Forres: Hints of early medieval grandeur

For me, some of the most tantalising scraps are the faint suggestions that three 10th-century kings of Scotland – father, son and grandson – all died in Forres, Moray.

They’re tantalising to me because Forres is central to the research I’m doing for my imminent MA. It’s an unassuming town which tends to trace its history back no further than c. 1150, when it was established as a royal burgh by king David I.

(Its associations with Macbeth, who ruled Scotland from 1040-1057, are no older than Shakespeare.)

The fact that there’s a huge and extraordinary carved stone near the town, dated by art historians to 850-950 AD, has always been treated as a mystery. Nobody knows why it’s here, who put it up, or what its images of violent battle, paired with a massive Christian cross and what looks like a royal inauguration scene, are meant to represent.

Three 10th-century kings who may have died in Forres

But there are hints in the manuscript sources that Forres may once have been a base for a branch of the dynasty that ruled Scotland (or rather its smaller forerunner, Alba) from 843 to 1034. These are the descendants of king Cináed mac Ailpin, (Kenneth MacAlpin), known to historians as the House of Alpin, or the Alpinids.

The three kings who may have died in Forres are:

Domnall mac Causantín (Donald II of Alba), grandson of Kenneth MacAlpin, who ruled from 889 until his death in 900, apparently at the hands of vikings.

His son Máel Coluim mac Domnaill (Malcolm I of Alba), who ruled from 943 until his death in 954, apparently at the hands of his compatriots.

His son Dubh mac Maíl Coluim (Duff of Alba), who ruled from 961 to 966, when, the sources unequivocally tell us, he was killed in Forres and his body hidden under the bridge of Kinloss.

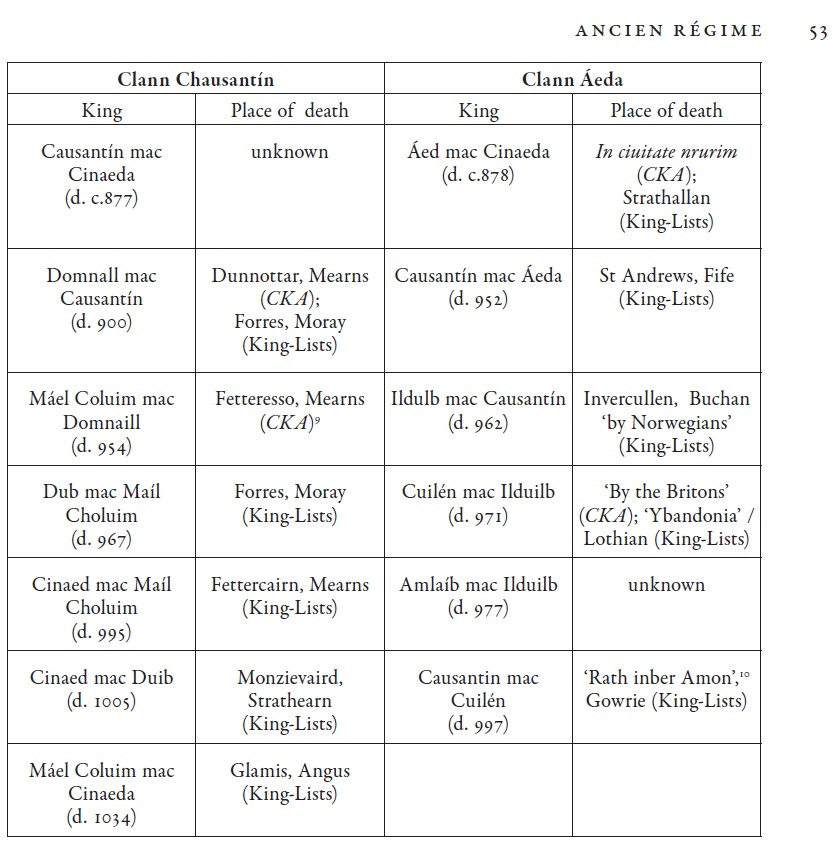

Eagle-eyed readers will have noticed that despite being father, son and grandson, these kings didn’t reign consecutively. The kings of Alba seemingly used an Irish form of succession, in which the crown alternated between two branches of the dynasty.

Donald, Malcolm and Duff were from the side of the family that historians call Clann Chausantín after Causantín mac Cinaeda, Donald’s father. The other side, Clann Aeda, were descendants of Causantín’s brother Aed, and have no obvious associations with Forres.

A quick guide to 5 key manuscript sources

So far, so good. But here’s where things get difficult. The manuscript sources offer conflicting and confusing information about where these kings died, and in what circumstances.

It’s probably a good idea to list the five key sources, as I’ll be citing them a lot:

The Annals of Ulster: The most reliable but least informative source. These are straightforward records of notable events that happened in a given year. Mostly they stem from records kept by monks in Ireland, but some may be based on records kept by monks on the Scottish island of Iona.

The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba (CKA): The most informative of the sources, but less straightforwardly reliable. The sole surviving version was compiled in the 14th century from a number of older sources – some reliable, some perhaps less so.

The Prophecy of Berchán: A poem written in the form of a prophecy, in which kings are referred to only by cryptic epithets and their deeds cloaked in metaphorical language. Using it to reconstruct the history of early medieval Scotland is like trying to reconstruct the history of pop music from the lyrics of Don McLean’s American Pie. Historians try not to touch it with a bargepole.

The Scottish King-Lists: A motley collection of manuscripts that all seem to derive from one or two early lists of the first kings of Scotland (or rather, Alba). The different versions are given different letters. Some of them only record the names and reign-lengths of the kings; others include other small scraps of information – including, for our purposes, the place and manner of their death.

The Chronicle of Melrose: A 12th-century manuscript compiled mostly likely by monks at Melrose Abbey, containing historical information drawn from other sources about kings and events in Scotland from 745-1140 AD.

Bear in mind that the surviving manuscripts are edited copies of edited copies, dating from the late middle ages or even later. Trying to figure out what’s original and what was added later – and where, when, who by, and for what purpose – has exercised historians of early medieval Scotland for decades.

I haven’t actually seen any of these manuscripts. I get their contents from two extremely useful books: Early Sources of Scottish History (1926) by Alan Orr Anderson, which gives English translations, and Kings and Kingship in Early Scotland by Marjorie Ogilvie Anderson, which presents CKA and the King-Lists in their original Latin (except version K, which is in Norman French).

The Death of Donald, Constantine’s son

So what do the sources tell us about the three kings who may have been connected with Forres? Let’s start with Donald I. First of all, the Annals of Ulster say, for the year 900:

Donald, Constantine’s son, king of Scotland, died.

Pretty uncontentious (unless you get into the phraseology used for ‘king of Scotland’, which I won’t).

Now the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba:

Donald, Constantine’s son, held the kingdom for 11 years. The Northmen wasted Pictland at that time. In his reign a battle occurred [at] innisibsolian between Danes and Scots; the Scots had the victory. Dunnottar was destroyed by the gentiles.

Lots to pick apart, but I’ll just say that some historians take the final phrase to mean Donald was killed at Dunnottar. The manuscript has it in Latin as: ‘Opidum Fother occisum est a gentibus’. No mention of Donald, but on the other hand ‘occisum est’ means ‘he was killed’, which is a strange thing to say about a fort. So perhaps Donald was meant after all.

Dunnottar crops up a lot

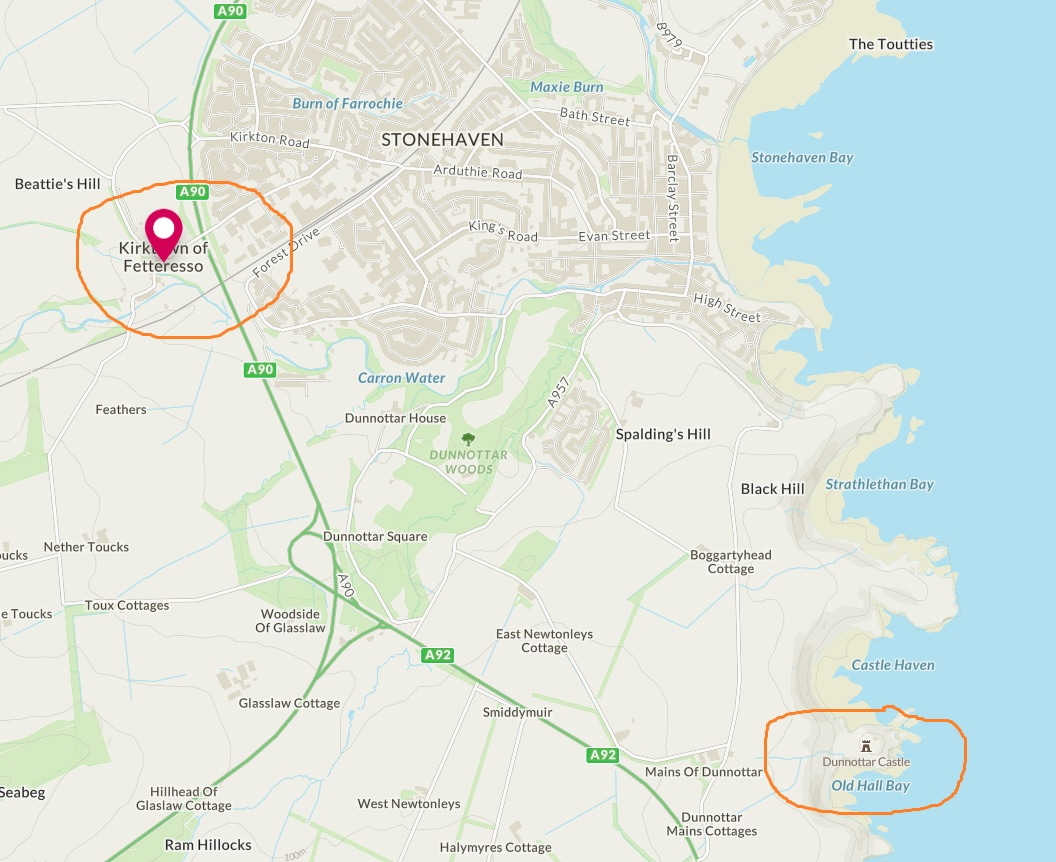

As we’ll see, this isn’t the only time that Dunnottar (an imposing promontory near Stonehaven) crops up in places where other sources suggest an association with Forres.

Next up, the Prophecy of Berchán, which casts Donald as “the rough one” and concludes:

He will have nine years as king, making the circuit of their boundaries, one after another, in every place, against Foreigners and against Gaels. The Gaels will turn against him secretly on the path above Dunnottar. He is on the brow of the mighty wave, in the east, in his broad gory bed.

Berchán also seems to suggest, then, that Donald was killed at Dunnottar. Or at least, at a place it calls ‘Fóther-dhún’, which Scottish place-name expert W.J. Watson (1926) identified as Dunnottar.

So Dunnottar is looking increasingly like the scene of the crime. But what’s this? King-Lists D, F, I and K make no mention of it, instead saying that:

Donald, Constantine’s son, reigned for 11 years, and he died in Forres, and was buried in the island of Iona.

Last but not least, the Chronicle of Melrose chimes in with:

[King] Donald reigned in Scotland; he was the son of Constantine. This king is said to have perished in the village of Forres, during the course of the eleventh year of his kingship.

NB If I’ve learned anything about medieval manuscripts, it’s that the phrase “is said to have” means the scribe has read it somewhere, but isn’t sure if it’s accurate or not.

So: Dunnottar 2, Forres 2. Which to believe? Among historians of the period, both Alex Woolf (2007) and Neil McGuigan (2021) favour Dunnottar, while Archie Duncan (1975) plumps for Forres. Difficult.

The Death of Malcolm, Donald’s son

On to Donald’s son, Malcolm I. Here’s the Annals of Ulster for the year 954:

Malcolm, Donald’s son, king of Scotland, was slain.

This scribe clearly didn’t get the memo about passive voice, so we don’t know who did the slaying or, crucially for this inquiry, where. But the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba says:

Malcolm, Donald’s son, reigned for 11 years. Malcolm went with his army into Moray, and slew Cellach. [Then a longish story about a cattle raid.] And the men of Mearns slew Malcolm in Fodresach, that is in Claideom.

Anderson notes that the 19th-century Scottish antiquarian William Forbes Skene identified ‘Fodresach’ as Fetteresso (which sits on a hillside above Dunnottar), and ‘Claideom’ as ‘Swordland’. Fetteresso is in a district called the Mearns, so according to CKA, Malcolm was slain by local Fetteresso nobles.

The Prophecy of Berchán, which bills Malcolm as “the Red Crow”, agrees with the place of death:

For a long time the Red Crow will take high Scotland of fair plains. […] He will have nine years in the kingdom, traversing their boundaries. An expedition on the brow of Dunnottar, the Gaels will shout above his grave.

This time, Berchán dispenses with “Fóther-dhún”, presumably for reasons of poetic metre, and instead calls the brow of Dunnottar “bra duna foiteir”.

So chalk up two again for Fetteresso/Dunnottar. But what’s this now? It’s King-List D with a slightly different version of events:

Malcolm, Donald’s son, reigned for nine years; and he was killed by the Moravians by treachery, and was buried in the island of Iona.

So this version of the King-List says Malcolm was killed by the men of Moray (Moravians), not the men of Mearns. It doesn’t venture a location, but versions F and I do:

Malcolm, Donald’s son, reigned for nine years; and he was killed [in Vlurn/in Ulnem] by treachery by the Moravians, and was buried in the island of Iona.

The Chronicle of Melrose seems to go along with that, adding some shade about the men of Moray for good measure:

King Malcolm succeeded [Constantine II], for nine years; he was the son of King Donald. The men of Moray slew him in Ulum: he fell by the deceit and guile of an apostate nation.

Where is this place Vlurn, Ulnem or Ulum? According to Anderson (who I’m guessing had it from Skene), it’s Blervie, now a ruined castle that sits on a ridge above – you’ve guessed it – Forres.

Alan Orr Anderson doesn’t think much of this version of events, saying that:

Berchán and CKA may be preferred to the other Chronicles of the Kings, which evidently mean that Malcolm fell in Blervie, Moray.

Among historians, both Woolf and McGuigan agree with Anderson that Malcolm was killed in Fetteresso, not Blervie. Duncan, meanwhile, rolls both tales into one, telling us that Malcolm was:

[P]erhaps otherwise preoccupied with rebellions by the men of Moray, who finally killed him in the Mearns.

So another Dunnottar/Forres quandary. And I can’t help but find it curious that Fetteresso is on a ridge above Dunnottar, and Blervie is on a ridge above Forres, both at very similar distances. Hmm.

The Death of Dubh, Malcolm’s Son

So finally to Dubh. I’ve written about him and his bridge-related death a few times already. But for completism, here’s the Annals of Ulster for 966:

Dub, Malcolm’s son, the king of Scotland, was killed by the Scots themselves.

Factual as ever, and this time we know who did the killing.

The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba goes oddly off-piste, semi-anonymising Dubh to ‘Niger’ – a translation into Latin of his name, which means “black” in Gaelic – and failing to mention his death at all:

[A battle was fought] on the ridge of Crup, and in it Niger had victory. And there fell Duncan, abbot of Dunkeld, and Dub-don, lord of Athole. Niger was driven from the kingdom, and Caniculus held it for a short time. Donald, son of Cairell, died.

So CKA is no help on the place of death. The Prophecy of Berchán also goes off-piste, by actually using Dubh’s real name:

Two kings reign over Scotland, both of them plundering equally: the White and the Black together. […] One of these kings will go on a futile expedition, across Múna in the plain of Fortriu. Though he goes, he will not come back again. Dub of the three black verses will fall.

There’s no place of death here either, except ‘Fortriu’, which is now identified with Moray. In fact, this verse of the Prophecy of Berchán was one of the key pieces of evidence that Alex Woolf used in 2006 to (sensationally) relocate the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu from the area around Perth and Dunkeld to the area around the Moray Firth.

King-Lists D, F, I and K, though, have all the goss:

Dub, Malcolm’s son, reigned for four years and six months, and he was killed in Forres, and hidden away under the bridge of Kinloss. But the sun did not appear so long as he was killed there; and he was found, and buried in the island of Iona.

The Chronicle of Melrose, seizing another opportunity to throw shade at the men of Moray, agrees:

Dub reigned for four summers and a half; a son of Malcolm, wielding authority. Him the treacherous nation of Moray slew; he was slain by their swords in the town of Forres. The sun hid its rays while [Dub] lay hidden under a bridge, where he was concealed, and where he was found.

So what’s the significance of Forres?

Every source that mentions a place of death for Dubh says he was killed in Moray, and specifically in Forres. Woolf, McGuigan and Duncan all accept this as the likely version of events (which does make me wonder why Woolf and McGuigan (below) favour CKA and the Prophecy of Berchán for the death-places of Donald and Malcolm).

So did all three kings – father, son and grandson – die in or near Forres? And if so, was it because they had a base there, or – given that Malcolm and Dubh seem to have been slain by the ‘men of Moray’ – were they there putting down local rebellions?

And is there anything behind the strange and seemingly persistent confusion between Dunnottar and Forres, Fetteresso and Blervie, the men of Mearns and the men of Moray?

Is Dun Fother even where we think it is?

This is all research of mine to come. But I will just finish by noting that when eminent archaeologists Leslie and Elizabeth Alcock undertook an excavation at Dunnottar in 1984, with a view to finding the Dun Fother of the early sources, they found no early medieval remains there at all:

The results of three weeks of strenuous excavation were surprising, and even perplexing. No finds or structures of early medieval date, or indeed earlier than the late 12th century, were discovered.

In fact, they expressly recommended that the site of Dun Fother be sought elsewhere – in their view, on the nearby promontory of Bowduns:

On present evidence, Bowduns is a more likely site for an Early Historic fortification than Dunnottar Castle itself; and that it is therefore appropriate to identify it as Dun Fother. Acceptance of this entails, of course, acceptance that the place-name has shifted between the 7th [when it first appears in the sources – FCH] and the 12th centuries.

As far as I’m aware, Bowduns has never been excavated. Given that Dunnottar is a very important place-name in the historical sources for early medieval Scotland – there are even records of it being ravaged by the English king Athelstan during his invasion of Scotland in 934 AD – might it be a future site for the University of Aberdeen’s Northern Picts project to investigate?

References:

L. Alcock and E. Alcock, Reconnaissance excavations on Early Historic fortifications and other royal sites in Scotland, 1974-1984 (1992)

J.R. Barrett, NOSAS in Forres: A Visit to the Royal Burgh (2016)

A. O. Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History A.D. 500 to A.D. 1286 (1922)

M. O. Anderson, Kings and Kingship in Early Scotland (1973)

A.A.M. Duncan, Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom (1975)

N. McGuigan, Máel Coluim III, 'Canmore': An Eleventh-Century Scottish King (2021)

S. Taylor with G. Márkus, The Place-Names of Fife, vol. 5 (2012)

A. Woolf, Dún Nechtain, Fortriu, and the Geography of the Picts (2006)

A. Woolf, From Pictland to Alba 789-1070 (2007)

W.J. Watson, The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (1926)

Hi Fiona, me again.

Perhaps the Northern Picts Project have already excavated Dhun Fothair! Perhaps Dunnicaer is the original Dunottar. Whilst promontory forts are common in the NE, it would be exceptional for two to be so close.

But Dunicaer is not big enough to support a late medieval fortification so when it came to it maybe they moved lock, stock and name to the current Dunottar? Dunicaer does sound a bit made up - the (Gaelic) fort of the (Brythonic/Pictish(?)) fort?