The river that moved and the lost lochs of medieval Moray

In which I investigate an extraordinary "fact" about the course of the River Findhorn in the middle ages

One of the things I love about early medieval Scottish history is that, as barely any writing has survived from the period, you have to try to piece together what happened from other types of evidence.

Archaeology, with its growing array of subdisciplines, is the main type, but there are others: place-names, carved stones with symbols, images and inscriptions, material culture, comparisons with better-documented contemporary societies, and more obscure ones like geology and palaeogeography.

In my MA application I said I was excited about using palaeogeography in my research, and I’ve been fretting ever since that the course convenor might have thought I meant palaeography, which is the science of deciphering historic handwriting (and thus a big deal in medieval studies).

But I did in fact mean palaeogeography, or the science of figuring out what the landscape looked like in the place and period being studied. In my case, because my research is anchored to Sueno’s Stone in Forres, that’s the western bit of the southern Moray Firth coast in the 9th and 10th centuries AD.

Yup, it’s Dubh and the bridge of Kinloss again (sorry)

Regular readers will recall that I’m particularly interested in figuring out whether or not there was a bridge at Kinloss in the 10th century, under which a medieval king-list says the murdered corpse of king Dubh (or ‘Dub’, or ‘Duff’) of Alba was hidden in 966:

“Dub, Malcolm’s son, reigned for four years and six months; and he was killed in Forres, and hidden away under the bridge of Kinloss. But the sun did not appear so long as he was concealed there; and he was found, and buried in the island of Iona.”

In 1984, historian Archie Duncan theorised that this bridge is depicted on Sueno’s Stone, with Dubh’s severed head in a box, Se7en-style, underneath it:

I grew up in Kinloss and know it well. So my first thought on reading the chronicle account of Dubh’s death was: why would Kinloss have a bridge? The only watercourse there is a tiny burn that you could jump over quite easily.

Sandstorms, floods and lost villages: Moray’s restless landscape

But that’s where palaeogeography comes in. The landscape of modern-day Moray is vastly changed from the landscape of Moray in the early middle ages.

In fact, the whole area is in continual flux: most local people could tell you about the lost village of Culbin that was buried by a sandstorm in 1694, for example, or the old village of Findhorn that lies under the sea near the current mouth of Findhorn Bay.

In the early middle ages, I eventually realised, the flat land around Kinloss – today a fertile agricultural plain known as the Laich of Moray – would most likely have been soggy, marshy ground.

The kind of ground that would be difficult to traverse unless (like Gollum) you knew a safe way through, but not the kind that would need an arched stone bridge, especially in a region where stone bridges were virtually unknown.

The river that moved

At least so I thought. But then I happened to be noodling about in Dr Alasdair Ross’s book Land Assessment and Lordship in Medieval Northern Scotland, in which he attempts to reconstruct the patchwork of land units known as dabhaichean (Scots ‘davochs’) into which medieval Moray was carved up.

Using medieval charters, deeds and place-names, Ross uncovers Moray’s davochs parish by parish, until he comes to Alves, east of Forres. Here he encounters a mystery: this must have been a large parish in medieval times, yet he can only find references to two davochs in the whole area.

This may be because the others were split up into different kinds of units early on, he speculates, before casually dropping this bombshell:

“A second possible reason […] could simply be due to the fact that there was a radical change in the path of River Findhorn c. 1100. Around this time the lower part of the river, which had previously discharged into the Loch of Spynie, moved several kilometres to the west to near the present position of its discharge. This shift must have had a major effect on landholding patterns in the vicinity.” [my emphasis]

Hmm, I thought. If the Findhorn originally flowed east of Forres, it might have flowed past Kinloss. So maybe there was a bridge after all. And that might explain why Andrew of Wyntoun, a 15th-century scholar who wrote an entire history of Scotland in rhyming couplets, thought Dubh’s body was hidden under a bridge over the Findhorn (see portion in bold below):

Quhen Indulf kyng wes dede away,

Dwlff wes kyng efftyre hys day:

In Murrawe dede efftyr he was

In the towne murthrysyd off Foras,

And karyd out off that towne wes he

Dede on a nycht in priwaté

Till a wattyr by rynnand

That cald is Fyndarne in Scotland:

In till a pwle wndyr the bryg

Thai kest hym downe, and lete hym lyg.

Bot thare wes newyre Sowne schenand

Thare sene, quhille he wes thare lyand:

And be the takyn of that thyng

Men trowyd, that thare than lay the Kyng.

I was quite pleased to have tied up that loose end. But then I thought: hang on. The River Findhorn “moved several kilometres” in a human-scale timeframe, maybe even a handful of years? And it used to discharge not into Findhorn Bay near Forres, but into Loch Spynie near Elgin? The more I thought about it, the more far-fetched this seemed. Is there any actual evidence for this?

It’s mappin’ time

Time to get the maps out! The first one I consult is the modern OS Explorer 423 1:25,000 map of Elgin, Forres and Lossiemouth.

I’m looking for any sign that the Findhorn could have followed a course from its present position at the bottom left of the map below to the Loch of Spynie - now virtually non-existent but remembered in the place-name Kintrae (‘head of the tide’), circled in orange at the extreme right of the map below.

One place-name catches my eye almost immediately. If you squint, you can see it circled in orange in the middle of the map above: Earnside. The old name of the River Findhorn, in use at least until the 12th century, was the Earn. Conceivably, then, Earnside was located on the bank of its old route.

Although… Earnside is a modern-sounding name. Its second syllable is English, and English (or more accurately Scots, a language closely related to English) wasn’t spoken in this area until after 1150, when David I established burghs at Elgin and Forres and populated them with incomers from southern Scotland, England and the Low Countries. According to Ross, the Findhorn had assumed its current course by that time.

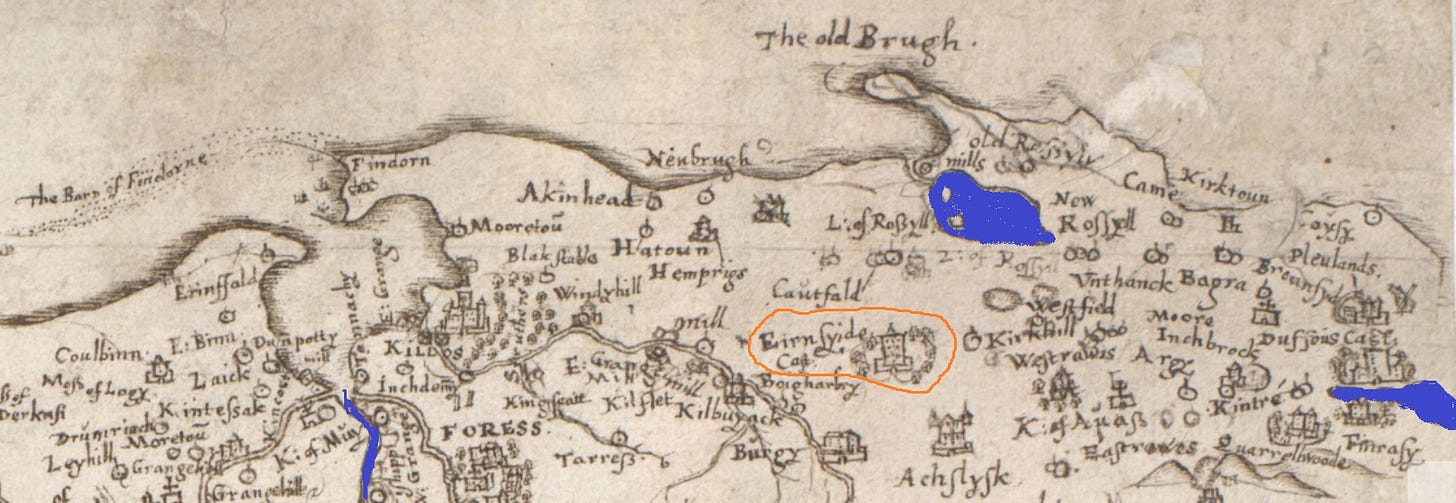

To see how modern it might or might not be, I check out the earliest detailed map of this area: Timothy Pont’s 1590 map of Moray and Nairn.1

It turns out Pont devotes a surprising amount of cartographic real estate to Earnside, or ‘Eirnsyide’ as he has it. It’s illustrated with a castle, a tower-house-type affair of the kind that were all the rage among the lairds of 16th-century Moray. (Pont drew most of his buildings from life, so we can assume that’s what it actually looked like.)

I’m briefly distracted by this. I used to live only a couple of miles from Earnside and I was really into castles, but I’d never heard of this one. I consult Historic Environment Scotland’s Canmore database, only to find that:

“Nothing is known of Ernside Castle except that it was built by the Cumyns of Altyr about 1450.”

(That sounds to be quite a bit more than “nothing”, but I’d better not go down this rabbit-hole now.)

Reconstructing Moray’s lost sea-lochs

Also on Pont’s map are the remnants of two sea-lochs that existed in the middle ages, but were progressively drained to create agricultural land. The Loch of Roseisle lay south of Burghead, and the bigger Loch of Spynie lay to the east, draining into the sea at modern-day Lossiemouth.

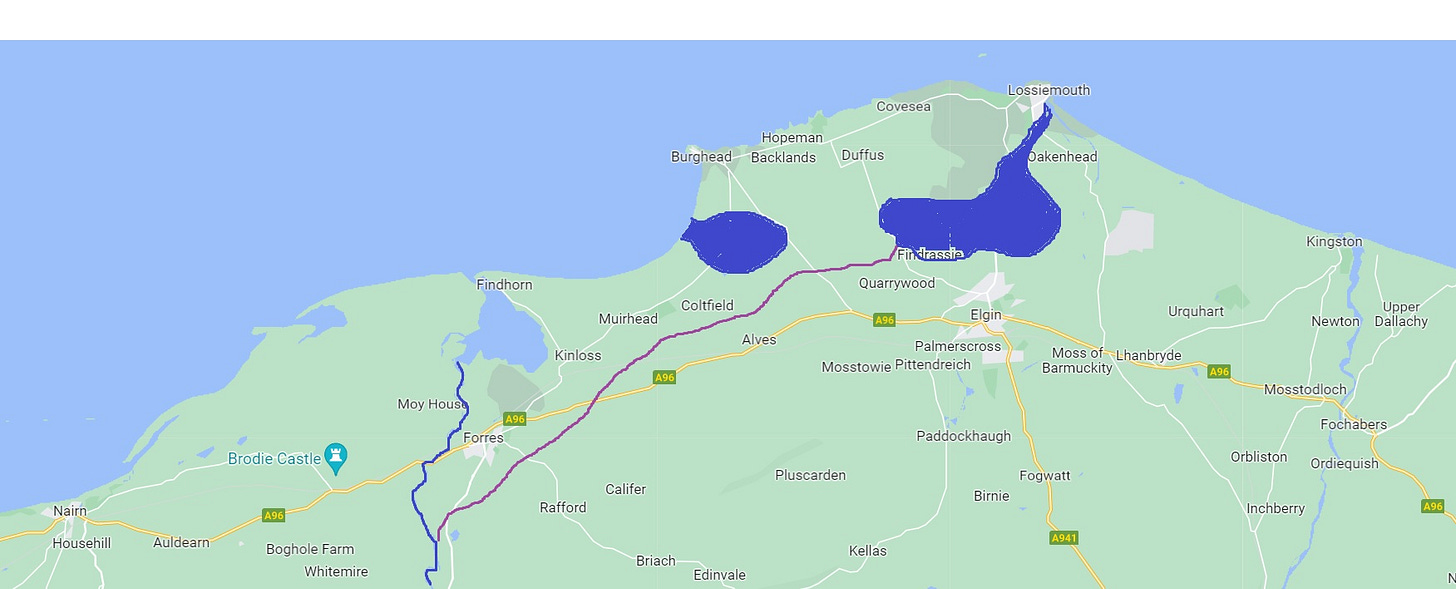

It’s into this bigger loch that Ross claims the Findhorn used to discharge. I do a quick mockup of the waterscape as it might have been in the 10th century, with the rough extent of the lochs, the current course of the lower Findhorn in blue, and its putative pre-1100 course in purple, passing Earnside on its way:

Vikings on the Findhorn?

Eventually, a tantalising thought strikes me. If this truly was the course of the Findhorn in the early middle ages, the land it passes through is flat enough for it to have been navigable from Spynie Loch all the way to Forres.

That would have created an inland waterway through what’s known to have been a high-status (and likely royal) area between the 8th and 10th centuries: the heart of the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu.

Even more intriguingly, as I mentioned a couple of blogs ago, one of Alex Woolf’s arguments for locating Fortriu in this area is this entry in the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba for the reign of Constantine II of Alba (d. 953):

“Causantín mac Aeda held the kingdom forty years. In his third year the Northmen plundered Dunkeld and all Albania. The very next year the Northmen were slain in Sraith Herenn.”

Woolf argues that “Sraith Herenn”, traditionally identified as Strathearn in Perthshire, could equally be the valley of the northern Earn – the Findhorn.

Could we imagine the Northmen, having plundered Dunkeld in 903, sailing north the following year to the Moray Firth, entering Spynie Loch (on the shore of which stood the Pictish monastery of Kinneddar, ripe for raiding), and creeping along the Earn towards Forres? And might we imagine that Constantine’s army met and slew them there, in one of the rare victories of the Men of Alba over the Scandinavian raiders?

In reality, that’s way too much speculation based on near-zero evidence. And I have to admit that one of the reasons I like it is simply that it has the vikings sailing past my old house, Muirhead, which is on the map above just north-east of Kinloss.

Did the Findhorn really flow past Kinloss, though?

In any case, when I eventually track down Alasdair Ross’s source for his extraordinary statement that the Findhorn moved several kilometres around 1100 AD, it turns out that source wasn’t quite as sure about it as Ross made out.

In their 1986 paper In Fines Borestorum: Reconstructing the Archaeological Landscapes of Prehistoric and Proto-Historic Moray, Professor Barri Jones and aerial surveyor Ian Keillar wrote:

“A major alteration in the lower Findhorn must have taken place about 1100 AD, when the east-flowing river, then discharging into the extended Loch of Spynie, changed course and entered the sea several kilometres to the west. This theory is not universally accepted by geologists, yet the names Pitearn and Earnside west of Alves indicate the former presence of running water.” [my emphasis]

It seems Jones and Keillar used the same place-name I’d noticed (I couldn’t see a Pitearn, which appears to be an older Picto-Gaelic name, and thus more convincing than Earnside) to support their argument for an earlier course for the Findhorn.

And it turns out that their own source for the river’s sudden shift was a 1928 book called The Lossie and The Loch of Spynie by H. B. Mackintosh, which I don’t have access to, but about which some geologists are clearly sceptical.

So I currently have no solid evidence that the Findhorn once flowed past Kinloss, which means I’m no further forward in establishing whether there was or wasn’t a bridge there in the late 10th century. But as ever, the thread has been an enjoyable one to follow, and I hope you’ve enjoyed it too.

References

J.R. Barrett, NOSAS in Forres: A Visit to the Royal Burgh (2016)

I. Cunningham, The Nation Survey’d: Timothy Pont’s Maps of Scotland (2001)

A. A. M. Duncan, The Kingdom of the Scots, in The Making of Britain: The Dark Ages (1984)

A. A. M. Duncan, The Kingship of the Scots, Succession and Independence 842-1292 (2002)

Historic Environment Scotland, Canmore database

B. Jones and I. Keillar, In Fines Borestorum: Reconstructing the Archaeological Landscapes of Prehistoric and Proto-Historic Moray (1986)

G. Noble et al, Kinneddar: A Major Ecclesiastical Centre of the Picts (2019)

Ordnance Survey Explorer map, Elgin, Forres and Lossiemouth (2015)

T. Pont, Map 8, Moray and Nairn (1590)

A. Ross, Land Assessment and Lordship in Medieval Northern Scotland (2015)

M. Stratigos, A Model of Coastal Wetland Palaeogeography and Archaeological Narratives : Loch Spynie (2021)

A. Woolf, Dún Nechtain, Fortriu, and the Geography of the Picts (2006)

A. Woolf, From Pictland to Alba 789-1070 (2007)

A. Wyntoun, Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland (c. 1420)

Pont’s endlessly fascinating map will appear a lot on this blog, and I’m very grateful to the National Library of Scotland for putting it online for all to browse.

This matter regarding the extent of Loch of Spynie is covered in an article at https://cushnieent.com/articles/LochSpynie.htm

You used this site "The Early Church in the North of Scotland" in your previous post about Pulvrennan and Knockando so I am surprised that you did not see it. The article was written in 1919.

To reference the Website in question I would ask you to use its proper title or its abbreviation ECNS not "on the Cushnie Enterprises website"!

Hello Fiona - a voice from the ghosts of your 6th form history course... also with an interest decades later in early medieval Moray, probably for very similar reasons. Saw your name pop up on the Northern Picts twitter feed.

Alastair and Helen's theories below could both be supported by the argument on page 114 of this https://pubs.bgs.ac.uk/publications.html?pubID=B01928, that the geological remains of shingle ridges and storm beaches around the modern mouth of the Lossie suggest that the Lossie and Loch Spynie were for some time blocked off from the sea east of Lossiemouth and instead were forced to empty to the west into Burghead Bay through the Roseisle/Alves gap. This subsequently silted up into marshland when access to the sea from the eastern end of the Loch opened up again, splitting the loch/estuary into the eastern Loch Spynie and the western Loch Roseisle. This does seem to have some respectable evidential basis beyond simple speculation around the local tradition of Vikings sailing past Kintrae/Roseisle/your old kitchen window (a tradition that the book is still sceptical about I'm afraid).

This would in turn suggest that the Findhorn wouldn't have had to meander anywhere near as far east as you'd imagine to have emptied into "Loch Spynie", it could conceivably have done so somewhere near, say Coltfield or Hempriggs, and could have done so passing north rather than south of Forres, which seems a bit more realistic. If the Lossie and the Findhorn both entered the sea together via Loch Spynie between Kinloss and Roseisle it could also support the theory that Kinloss might be named after its relationship with the Lossie, and explain why the tiny Lossie/Loxa but not the much larger Findhorn seems to have been recorded by Ptolomy. It is hard to see any of this still being the case as late as 1100 though?

Stratigos' recent paper on the subject (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14732971.2021.1930775) seems to disagree, but without directly mentioning or rebutting the 1968 book. His model has Loch Spynie and Loch Roseisle as always essentially separate, as with your map above. His analysis does seem primarily to be based on changing water levels in the context of constant back-projected modern contours though, so might miss the effects of the movements of silt and sand and shingle causing land contours to change, which seems such a well-recorded feature of the area's history, and which the 1968 book with its geological approach seems to focus on more.

(On the other hand Stratigos is a leading academically authoritative wetland paleogeographer and archaeologist and I'm a random bloke on the internet, so who am I to comment?)