In search of the Altyre Cross

In which I try to track down the original site of an early medieval cross-slab

A couple of weeks ago, a tweet by the Stone Club got me thinking about the Altyre Cross – an early medieval cross-slab that today stands in a field on the Altyre estate, just south of Forres.

Like the Kebbuck Stone, the Altyre Cross is another Class III stone that doesn’t get a lot of attention, probably because its carving is quite plain and almost worn away, and it doesn’t have any Pictish symbols on it.

Stone Club member Keshia Glover wrote a short blog about it, noting:

These early Christian Ogham stones are often testaments to land ownership; one's belonging in place, but even it's location origin is uncertain. It is said it was moved here in the early 19th century.

This sparked something in the back of my mind, because I thought the original location of the Altyre Cross was known. I knew it had come from a field on the Laich of Moray (the coastal plain north of Elgin and Forres), but I couldn’t remember where on the Laich, or what exactly I’d read about it.

This seemed like a good prompt to try to recover the information I’d lost. Off I went, confident I would shortly be able to settle the question of where the cross was originally situated.

As it turned out, this became much more of an epic quest than I had suspected; eventually involving correspondence with two brilliantly helpful Moray folk, much poring over a copy of a copy of an 18th-century estate map, plus a (bargain) eBay purchase of a first-edition antiquarian book from 1839.

Conflicting claims in Canmore

My first port of call for questions like this is usually Canmore, Historic Environment Scotland’s excellent database of historical and archaeological sites and finds across Scotland.

Here, though, confusion arises instantly. The first entry is archaeologist Anna Ritchie noting in 2018:

Evidence for discovery: Recorded as standing on rising ground in a field belonging to Longhillock Farm and moved around 1800 to a field north of Altyre House.

This sounds pretty definitive. But the next entry, attributed to the Ordnance Survey, offers:

The sandstone pillar at Altyre was brought there from the Laich, probably about 1820. According to the late H. W. Young of Elgin it came from the college field at the village of Roseisle (J R Allen and J Anderson 1903).

Then there’s a note added in 2014 by Janet Trythall of Elgin Museum:

The Altyre cross slab was brought to its current location on the Altyre estate from Longhillock Farm, Duffus Parish, area NJ 141 641.

Are these locations all one and the same place? A glance at the map would suggest not. The ‘college field at Roseisle’ was presumably somewhere around the hamlet of College of Roseisle, whereas the farm of Longhillock is a couple of kilometres due south of there. (Both places circled in red below.)

Anna Ritchie’s wording suggests the Longhillock location is based on documentary evidence, while the College of Roseisle location seems to be based on the word of Hugh W. Young (1845-1910), laird of nearby Burghead and a keen antiquarian.

The mention of the college field is sourced to Early Christian Monuments of Scotland, the epic two-volume survey of early medieval sculpture by John Romilly Allen and Joseph Anderson, published in 1903 by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

I have a much-treasured version of the 1993 reprint of this book, but the original is available free here. The entry for the stone reads:

The stone is said to have been removed from the parish of Duffus, 5 miles N.W. of Elgin…

A footnote reads:

Mr Hugh W. Young, F.S.A. Scot., of Burghead, informs me that the original site was the college field at the village of Roseisle.

So what about the other location: “on rising ground in a field belonging to Longhillock Farm”? Anna Ritchie notes that this information has been ’recorded’ – but where? There’s an answer of sorts in Janet Trythall’s 2014 note, which continues:

Bennett, Susan The Original Location of the Altyre Stone, in Pictish Art, a record of the conference held by Elgin Museum and The Moray Society 22nd and 22rd August 1998, p. 18-20. (Elgin Museum 1999).

So Susan Bennett of Elgin Museum gave a lecture on the location of the stone in 1998, which was written up and published the following year. I can’t find this publication anywhere online, so this particular line of enquiry temporarily goes cold for me.

Digging deeper: Stuart, Calder and Jackson, Forsyth

But there are other leads to follow up. Collectively, the first two Canmore entries cite three other sources: Stuart 1856, Calder and Jackson 1957, and Forsyth 1996. So what are these sources, and what do they have to say?

Stuart 1856

Stuart 1856 is an easy one. That’s John Stuart’s Sculptured Stones of Scotland; the first concerted initiative to record and sketch all of Scotland’s early medieval carved stones, and still a valuable resource today. It’s available as a free PDF here.

Here’s what Stuart says about the stone:

‘The Altyre Stone was found, it is said, about [the Parish of] Duffus, and was transferred to the position which it now occupies [at Altyre, near Forres]. There appear to be faint marks of Runic knots on this stone, or other carvings. Its height is fifteen feet.’ The marks of ornament seem now to have disappeared.

A closer look reveals that almost all of Stuart’s commentary is a quote from somewhere else, with his only additions being the clarifications in square brackets and the observation that “The marks of ornament seem now to have disappeared.”

So who was Stuart’s source for the stone having been moved from the parish of Duffus? A footnote says:

Sketches of Moray, by Rhind, pp 129-130, Edin 1839

I go to Google, and search for Rhind Sketches of Moray 1839. The internet tells me there is one copy on sale, for £250, from Leakey’s Bookshop in Inverness.

Now, I love Leakey’s and it’s officially one of the most beautiful bookshops in the world. But I definitely don’t have £250 to spend on a 144pp book that might not even have any useful information in it.

I try eBay, where I find a first edition for sale with a starting price of £10.50. This is more like it! I put in a bid and resume my quest.

(Sidenote: when I eventually win this auction - for £32 - and the book duly arrives, it indeed doesn’t have any further useful information in it. But I have a very nice first edition of an antiquarian book about Moray, so I’m happy.)

Calder and Jackson 1957

Next up is Calder and Jackson. This turns out to be a 1957 paper called An Inscription from Altyre, which is available as a free PDF from the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

However, it transpires that Calder (William) and Jackson (Kenneth) are more interested in the ogham inscription on the slab than in where it originally came from. Having asked around to no avail, Calder declares:

I am content to quote (from Allen) the considered opinion of the late H.W. Young, F.S.A. Scot., of Elgin, a skilful and careful antiquary, that it was taken to Altyre ‘from the college field at the village of Roseile’.

He does provide a bit of colour by noting that the stone was brought to Altyre in about 1820 “by the contemporary laird of Altyre or his brother”, specifically for use as “a rubbing stone for cattle”. He concludes, rather pollyannaishly, that:

In this charmingly bucolic context it would be churlish to complain that no record was kept of the provenance of the pillar, or of its siting or setting.

A statement which prompts a Paddington-style hard stare from our final source:

Forsyth 1996

This is the PhD thesis of Katherine Forsyth (now Professor Katherine Forsyth of Glasgow University), titled The Ogham Inscriptions of Scotland: An Edited Corpus. It proves tricky to track down, but I eventually find it on the academic ‘dark web’.

It’s a superb survey of all of the then-known ogham inscriptions in Scotland, with transliterations, notes towards interpretation (the inscriptions are famously difficult to decipher), and—crucially for my investigation—notes on the original locations and landscape settings of the inscribed stones, which Forsyth believed to be essential to understanding the inscriptions.

Forsyth cites Calder’s comment that the stone was brought from the Laich, reiterates Hugh W. Young’s assertion that it came from the college field at Roseisle (while noting that “there is no further authority to support this tradition”), and adds another possibility into the mix:

Norman Atkinson, Curator of Angus Museums, has suggested that the stone may, in fact, have come from the Ogstoun. The site now occupied by the 'Michael Kirk' of Ogstoun was prominent in the later Middle Ages, as indicated by the surviving sculpture there, but fell out of use in the early modem period.

This is quite a radical departure from the other two supposed locations, which are both in the west of Duffus parish. The Michael Kirk is on the east side of the parish, in the grounds of what’s now Gordonstoun School.

Plus, given the tradition that the stone came from ‘the Laich’ rather than an identified place, it’s likely that it came from a setting in which the stone itself was the main landmark; and once it had been moved the site became unremarkable, and thus easily forgettable. On that basis, a field seems a far likelier place than a church yard.

(Compare with the other ogham-inscribed Pictish stone in the area, Rodney’s Stone at Brodie Castle. It was also moved to its current spot in the early 19th century, but it’s well remembered that it came from Dyke Church, where it was found when the foundations for the church were dug in 1781.)

Time to get the maps out

So I’m back to the two front runners: College of Roseisle and Longhillock. The former is starting to feel a bit fishy. As Forsyth notes, no source other than H. W. Young mentions it, and wherever Young got his information, it wasn’t from personally witnessing the stone’s removal. If it was moved around 1820, it would already have been at Altyre for more than 20 years when Young was born in 1845.

What about Longhillock, then? Anna Ritchie’s Canmore entry says the stone was originally located “on rising ground belonging to Longhillock Farm”. This rising ground should be easy to spot on a map, I think. In fact, might the stone even be marked on an old map?

(I assumed researchers would have scoured all of the available maps already, but I never need much of an excuse to look at old maps!)

I try a selection from the National Library of Scotland’s online digital map archive—from Timothy Pont’s 1590 map of Moray, to William Roy’s map of Scotland, drawn up around 1750 in the wake of the battle of Culloden, to the first Ordnance Survey six-inch map of the area, surveyed in 1870.

Spoilers: the stone isn’t shown on any of them (unless you count the OS six-inch map, which I’ll come to in a moment). What did become very apparent straightaway, though, was a couple of place-names in the immediate vicinity of Longhillock Farm that seem almost laughably significant.

Here’s Roy’s c. 1750 map of the immediate area, for example. Longhillock is marked as a farm township with field strips to its west, north and east. If Susan Bennett and Anna Ritchie are correct, the Altyre stone will have come from one of these fields.

But immediately to the north of Longhillock is another farm township, called Standing Stone. Wouldn’t the stone more obviously have come from here? Especially as this farm is on rising ground at the eastern end of a hill called Kirkhill, whereas Longhillock is on comparatively low-lying ground.

And what about Kirkhill itself? ‘Kirk’ is ‘church’ in Scots, so the name suggests this hill might once have had a church on it, although there’s no evidence of one today. The Altyre stone is a cross-slab, which were often associated with early Christian churches. Could it have originally stood on Kirkhill?

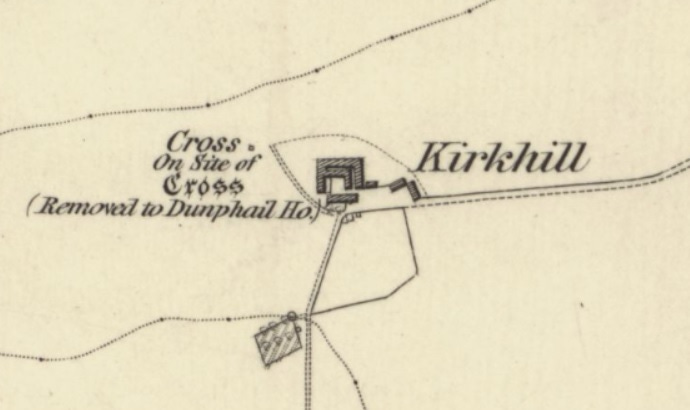

It’s here that the OS six-inch map manages to confuse matters even further:

It records a cross standing at Kirkhill, apparently as a replacement for an earlier and more ancient cross (as indicated by the gothic script). According to the map, this earlier cross was ‘removed to Dunphail House’ at an unspecified date, but clearly before 1870 when the OS survey was made.

This is where things get weird. Dunphail House was built in 1828 for Major Charles Lennox Cumming Bruce, brother of Sir William Gordon-Cumming—the laird who is said to have brought the Altyre cross to Altyre House.

Are we to believe that these two brothers each removed an ancient cross from neighbouring farms on the Laich, and brought them to their respective country houses? And if so, what happened to the one that went to Dunphail? There’s no record of an ancient cross there (at least, not in Canmore).

Or was there only ever one ancient cross, and it was removed from Longhillock (or Standingstone), not Kirkhill, and it went to Altyre House, not Dunphail House, and the remover was William Gordon-Cumming, not his brother Charles Cumming Bruce?

At this point I’ve exhausted all the sources I have access to, and I still can’t say for sure.

A detour through the archaeology of Easterton of Roseisle

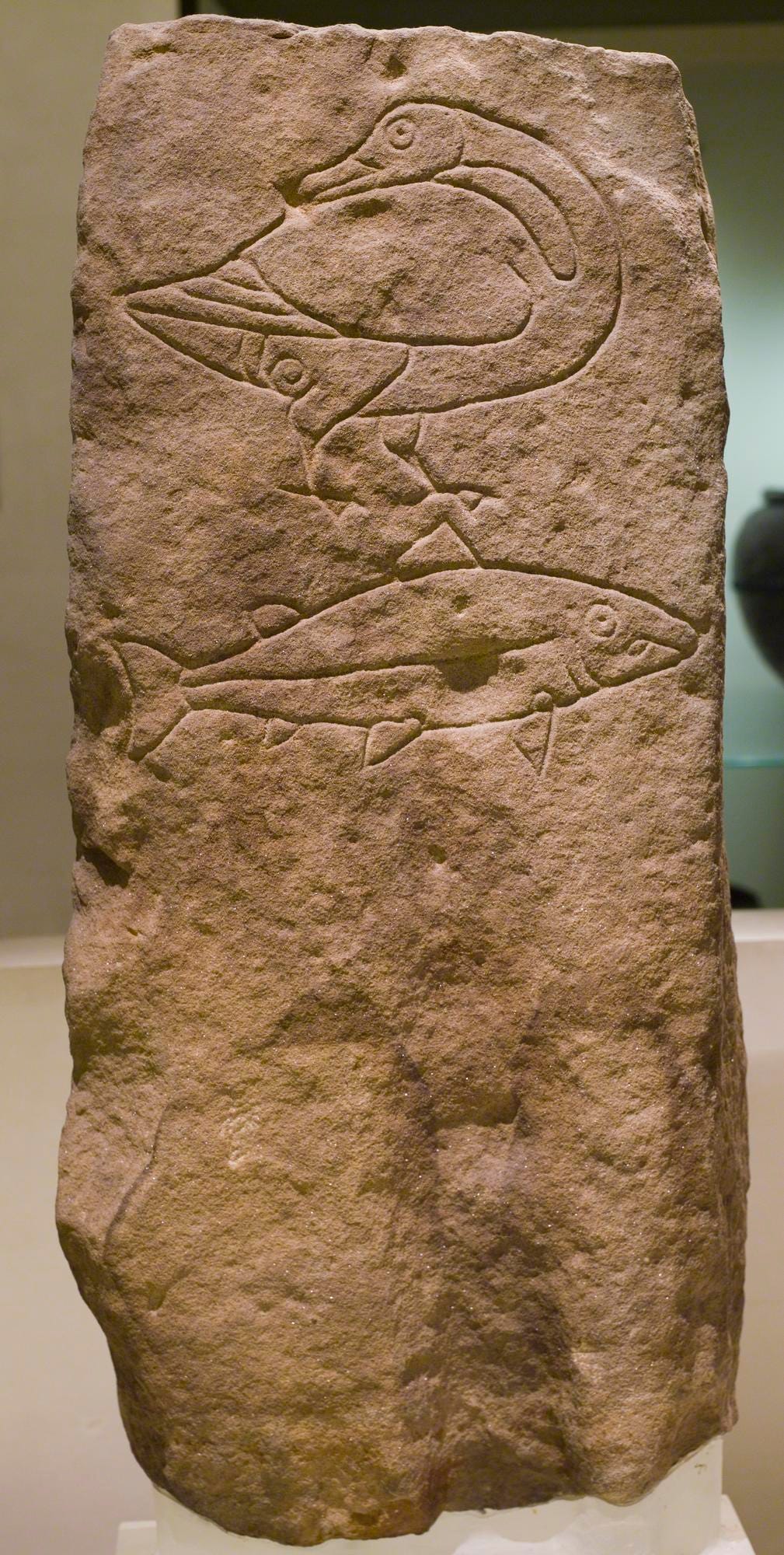

Meanwhile, it’s been kicking around in my mind that both Longhillock and Standingstone adjoin a third farm, Easterton of Roseisle, where a series of archaeological discoveries, including a very fine Class I Pictish symbol stone, was made in 1894 and 1895.

These discoveries were written up in 1895 for an antiquarian journal called The Reliquary and Illustrated Archaeologist, by none other than Hugh W. Young; he of the possibly-misremembered information that the Altyre stone came from the college field at Roseisle.

I’ve had a reprint of this journal for a long time, and on re-reading it, it struck me just how extraordinary the finds were. Firstly, the Pictish symbol stone—which are usually standing monuments—had been used as one side of an irregularly-shaped stone cist grave, apparently containing two early medieval burials.

More extraordinarily, this cist had been placed next to what seems to have been a much older—perhaps neolithic—burial site, containing ‘hundreds’ of skeletons. Near to these two sites lay 14 circular features which Young interpreted as hearths.

An excerpt from Young’s write-up reads (content warning: burial description):

The skeletons […] occupied a space of about fifty yards long by thirty yards broad, and all the burials seem to have taken place at one time. The skeletons were laid in rows, so close together that the bodies must have been almost touching each other, and they lay on their backs north and south. There was some appearance of an earthen wall round the burial place, and it had been divided diagonally by a wall of clay.

A new lead arrives from Twitter!

Struck by this, I post a photo of the article on Twitter, along with a photo of the symbol stone. This prompts a reply from Sue Bedford, who lives in College of Roseisle, to say the goose and salmon symbols from the stone form the logo of the village hall there.

On the off-chance, I ask Sue if she knows which field Young might have meant by “the college field at Roseisle”. She very kindly photocopies for me three pages from a local community-published book from 2000 called Roseisle Remembered.

Here is a leap forward at last! Of the Altyre slab, the book says:

Why it was erected we will never know, but evidence of its original location has now come to light. Susan Bennett, Curator of the Elgin Museum, by studying the letters of George Gordon (1801-1893) in the Gordon Archives, has found the answer, and her account of the relevant correspondence makes interesting reading.

There is then a quote from Susan Bennett:

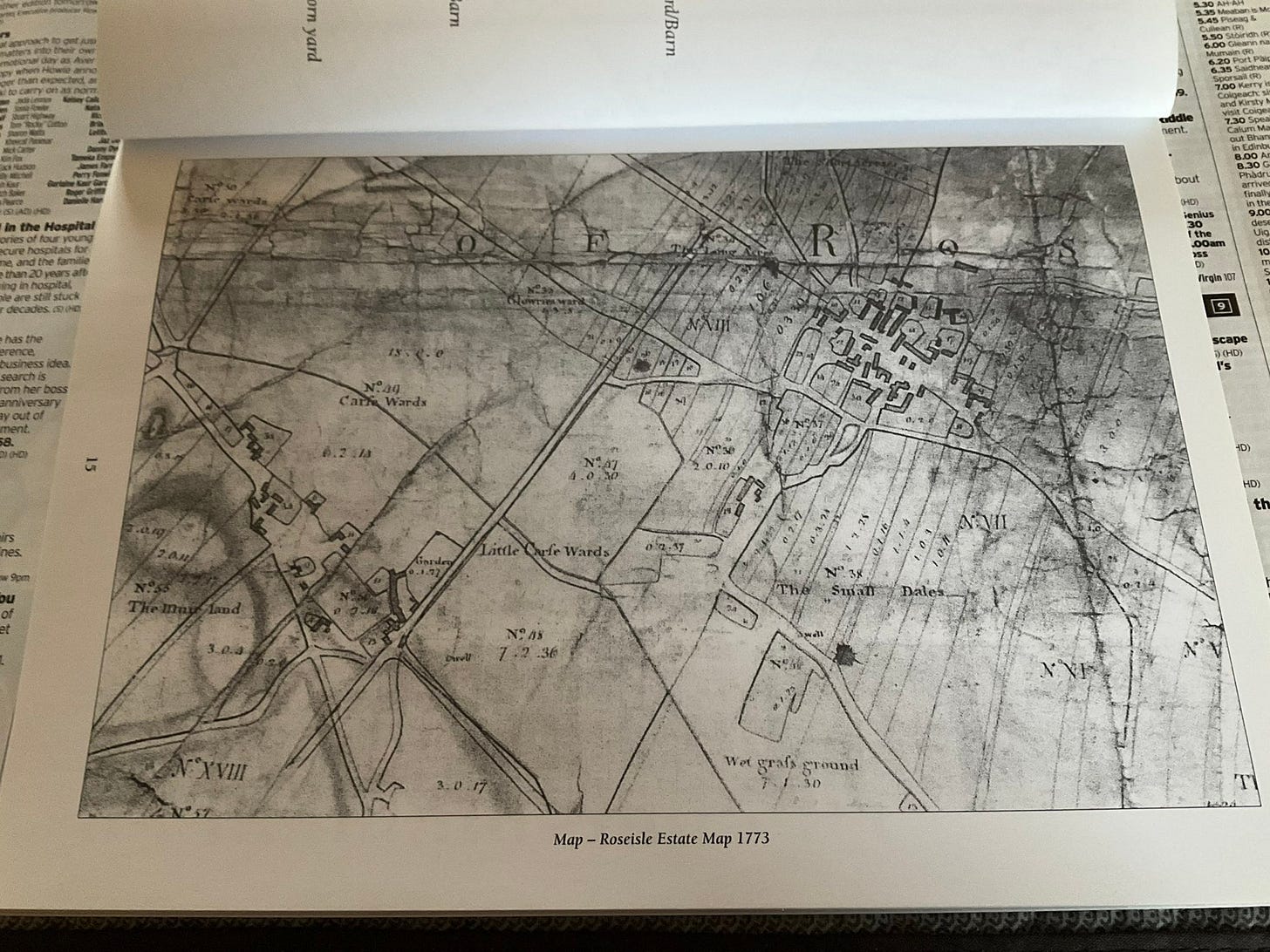

The site of the ‘Lang Stane’ was almost certainly to be found in a field to the East of Longhillocks Farmhouse. To confirm this, 1773 Roseisle Estate Map shows the position of a standing stone in field no 7 of Longhillocks Farm.

This seems like the clincher. This 1773 estate map is even reproduced in the book:

However, try as I might, I can’t locate anything that could be interpreted as a standing stone. I can’t even identify Longhillocks Farm or field no. 7 with any certainty—though perhaps it’s the large field labelled No VII towards the right-hand side.

After much zooming in, and even drafting in my kids to help, I admit defeat.

Confirmation from Elgin Museum

But there’s one more place to try. The Canmore note from Janet Trythall of Elgin Museum cites a talk given by Susan Bennett in 1998 on the original location of the stone.

I’ve already solicited Janet’s help once before, when I was on the trail of the Kinloss Stone. Might she be able to help again? I email asking if the talk notes are available to purchase anywhere.

Once again I receive a very swift and very helpful reply (as a result of which I’ve set up a regular donation to Elgin Museum—support your museums; they provide a very valuable service!)

Janet sent me a photocopy of Susan Bennett’s talk notes from 1998; the results of her research among 1,300 letters of correspondence of George Gordon in the museum’s Gordon Archives.

Gordon’s initial correspondence is fraught with confusion about different crosses and potential sites. But eventually, a location is confirmed by a local landowner, John Sutherland of Shempston. Sutherland writes to Gordon:

Dear Sir, In an old plan of Roseisle Estate, drawn from a survey of 1773, the long stone now at Altyre now appears standing about the middle of the farm of Longhillock…

He even has an eye-witness:

I went to Roseisle last night and got the ground officer to point out the spot where the Stone stood, he having been there at the removing of it 46 to 48 years ago.

And intriguingly:

He says that by digging a very short distance the small stones that were supporting the long one could be found, they having been turned into the hole and buried there.

Bennett then notes that while the correspondence ends here, “there is a scribbled note in pencil in one of Gordon’s notebooks”, reading:

Site of pillar: 235 space from east end of farmhouse (Mr Laing) in a line with two chimes [sic] 100 space from road between Burgh road.

‘O’ marks the spot

So finally, after two weeks’ research, there I have it: exact instructions, treasure-map style, for finding the socket stone(s) for the Altyre Cross in its original location, “235 space” (‘paces’?) from the east end of Longhillock farmhouse.

If it was also situated ‘on rising ground’, by my reckoning that would place it on the 15m contour hillock (from which I assume Longhillock got its name) marked with a red circle here:

As Hugh W. Young pointed out in his account of the discoveries at Easterton of Roseisle, and Katherine Forsyth observed in her PhD thesis, this hillock would once have been a low island in the Loch of Spynie, prior to its 18th-century draining.

Why did the Picts erect a huge 3m cross-slab on a small island? Forsyth concludes:

If Roseisle was the original home of the Altyre slab, it may have stood on the route towards Burghead.

That brings me a little bit closer to assembling an idea of the routeways through the marshy lowlands of Moray in the early medieval period. But after two weeks of research and 3,421 words to get this far, that has to be a topic for another time…

References

S. Bennett, The Original Location of the Altyre Stone, in Pictish Art (Elgin Museum, 1999)

W. M. Calder and K. Jackson, An inscription from Altyre (1957)

C. Clerk, Burghead, Moray: A history of archaeological thought (2019)

K. Forsyth, The Ogham Inscriptions of Scotland: An Edited Corpus (1996)

J. Stuart, Sculptured Stones of Scotland (1856)

W. Rhind, Sketches of Moray Past and Present (1839)

J. Romilly Allen and J. Anderson, Early Christian Monuments of Scotland (1903)

Roseisle Remembered, community publishing project by the Roseisle Group (2000)

H. W. Young, Discovery of an Ancient Burial Place and a Symbol-Bearing Slab at Easterton of Roseisle (1895)

Great to get to the bottom of the original location of this stone - bravo! We are hoping to scan it next year for the OG(H)AM project. I'll keep you posted.

Fabulous Fiona! A couple of thoughts in reading... first is that it is rare to find a cross stone that isn't at a church, it does happen, but rarely, suggesting something else is being marked. Second, that with an ogham it suggests we might be at a burial ground of significance. Then the place you've landed on is only a couple of hundred metres to the south of that massive burial ground where 100s of bodies were found, said to be 'Neolithic' but that is doubtful. So could the cross be marking this burial event? What's then interesting is that the actual location of the burial ground is well, sort of rubbery as well. Perhaps you should have a go at locating that next? :-)