Rodney’s Stone: A Class II Pictish symbol stone from Dyke, Moray

In which I see if I can come up with anything new to say about this well-known stone

I’ve been meaning to write a blog about the so-called ‘Rodney’s Stone’ at Brodie in Moray ever since I started this blog in April this year.

We were on holiday in Nairnshire at the time, and this was one of the Pictish stones we went to visit on our trip:

The reason I haven’t written about it is because I wanted to try to shed some new light on it, and I’m not sure I can. But I can at least put a number of already-known things about it together to see if they elicit any new thoughts.

My general aim—as I’ve done in my blogs about the Altyre Cross, the Princess Stone and the Kebbuck Stone—is to think about why it was situated where it was, what purpose it might have served, who created it or had it created, and what (if any) connection it had to other stones and sites in the area and further afield.

So this blog will be just that – a collection of facts and scholarly opinion about the stone that might help to answer all or any of those questions. My plan is to just start writing and see if it takes me (and you) anywhere interesting.

A Class II Pictish symbol stone

So first, the basics: Rodney’s Stone is a Class II Pictish symbol stone, meaning it’s carved in relief and bears Christian and Pictish symbols; in this case, a cross on one main face and the ‘Pictish beast’ and double-disc and Z-rod symbols on the other.

Dating of early medieval stone sculpture is always problematic, but according to Professor Katherine Forsyth’s 1996 PhD thesis surveying all of the then-known ogham inscriptions in Scotland, the art historian R.B.K. Stevenson dated it to c. 850 AD. I can’t claim any knowledge that might lead me to dispute that date, so let’s go with it.

Rodney’s Stone is also one of only 25 or so Pictish symbol stones to include a written inscription, expertly carved using the Irish ogham script and running for almost 4 metres around the edges of the stone. Sadly the carving is so weathered that only one word can be made out: EDDARRNONN – generally thought to be the personal name ‘Ethernan’, and perhaps more specifically the saint of that name who died in 669 AD.

Today the stone sits in the eastern driveway of Brodie Castle, the seat of the Brodie family since its construction in 1567. But its original location was a kilometre or so further east, in the graveyard of Dyke Church, where it was found in 1781 by builders digging the foundations for the current church.

In 1782, Admiral George Rodney of the British navy won a battle with the French fleet off the coast of Dominica, and tradition holds that the re-discovered stone was named in honour of his victory.

A short ‘petronymic’ detour

However, for fans of ‘petronyms’, as Katherine Forsyth has recently dubbed the often-misleading names given to early medieval carved stones, it’s worth noting that this tradition was disputed in around 1903 by the minister of Dyke Church, John McEwen.

In her 1996 thesis, Forsyth wrote:

An alternative tradition concerning how the stone got its name is preserved in a note made by J. Graham Callander in the margin of the copy of ECMS [Early Christian Monuments of Scotland] in the library of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in Edinburgh.

She continued:

Citing the authority of the Rev. John MacEwan the minister of Dyke, [Callander] states that the stone was dug up by a gravedigger ‘locally known as Rotteny’, and that it was after him, not the Admiral, that the stone was so called.

However, she concluded:

[George F.] Black lists no such name in his definitive survey of Scottish surnames […] For all that it is now beyond proof, the admiral seems the more likely eponym than the gravedigger.

But we might give Rev. McEwen slightly more credit, as he doesn’t strike me as the kind of person who would convey baseless rumour to the Director of the National Museum of Antiquities.

He was a keen antiquarian (he co-conducted the excavation of the Pictish Class I stone at Easterton of Roseisle in 1895), the brother of Glasgow-based astronomer Henry McEwen, and sometime curator of the Falconer Museum in Forres.

This scientific background makes me think he would have to be confident in his information before passing it on. Callander’s note suggests that ‘Rotteny’ may have been a nickname, rather than a surname, so could McEwen have been correct after all?

UPDATE 9th Oct 2022: I was just reading Thomas Lauder’s 1830 account of the severe flooding (the ‘Muckle Spate’) of the Findhorn in 1829, which includes this, from an account of Dr Brands of Forres’s visit to Moy House during the flood:

After dinner Mr Suter accompanied Dr Brands to visit a cottage on the embankment, tenanted by James Findlay, a boatman, better known by his nom de guerre of ‘Old Rodney’.

Could ‘Old Rodney’ the Findhorn boatman and ‘Rotteny’ the Dyke grave-digger be one and the same person, glimpsed 48 years apart in 1781 and 1829?

Later re-use as a grave marker

In any case, although 1781 is usually given as the date for the stone’s discovery, it had already been ‘re-discovered’ at least once in the post-medieval period. Its cross face bears the initials AC and KB, carved upside down in relation to the cross, suggesting it had been re-used at some point as a gravestone—or more likely as a recumbent grave cover, since the cross face is more weathered than the symbol-bearing face.

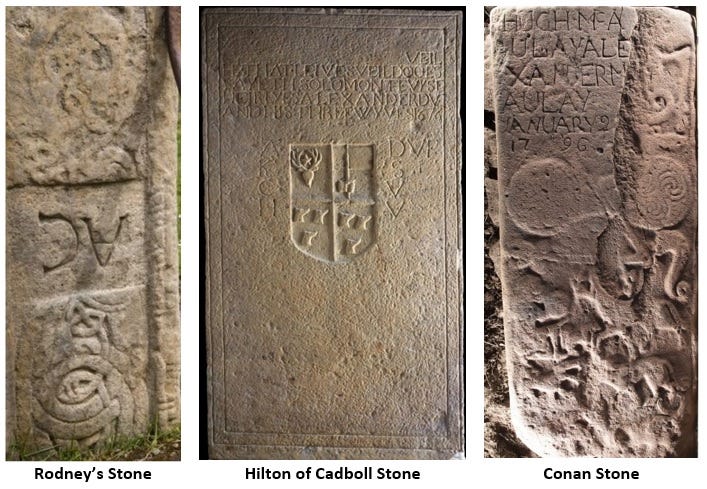

This kind of re-use of early medieval cross slabs was relatively common from the 16th to the 18th century. As well as Rodney’s Stone, both the Hilton of Cadboll cross-slab from the Tarbat peninsula, and the recently-rediscovered ‘Conan Stone’ from Logie Wester near Conon Bridge, were re-used in this way, along with many others.

The circumstances leading to this type of re-use were often complicated, and well explained by Professor Sally Foster (University of Stirling) and colleagues in their excellent—and free to download—2021 book: A Fragmented Masterpiece: Recovering the biography of the Hilton of Cadboll Pictish cross-slab.

In essence, what may seem to our eyes like thoughtless and even sacrilegious defacement may actually have helped to preserve monuments like Rodney’s Stone.

Scotland went through two phases of major religious upheaval in the post-medieval period; the Reformation in the mid-16th century and the Covenanting period in the mid-17th. In both phases, buildings and materials associated with the Catholic church were defaced, destroyed or left to fall into ruin.

Some Pictish stones were thus left at the mercy of the elements, others were moved or buried for safe-keeping, many were broken up for building stone, and some were re-appropriated as grave stones.

Some stones experienced more than one of these eventualities in their long after-lives. The Hilton of Cadboll slab, for example, was neglected after the chapel where it stood went out of use in or after the Reformation, then seems to have been toppled by a gale in 1674 before being re-used as a grave slab two years later.

By re-appropriating Rodney’s Stone as a grave marker, the relatives of ‘AC’ and ‘KB’ ensured—wittingly or not—that the stone survived largely intact. And by placing it cross face upwards on top of the grave, they preserved the Pictish symbols and designs on its reverse, as well as the section of ogham script that can still be read. Rather than tutting at them, we should probably be grateful.

Why was Rodney’s Stone located in Dyke?

But what was Rodney’s Stone doing in Dyke churchyard in the first place? This is actually quite an easy question to answer, since all the evidence points to this having been a Christian site since the first millennium AD.

In her 1996 thesis, Forsyth noted that:

Dyke church sits on a large mound within an oval enclosure, two features usually taken as diagnostic of an early medieval antecedence. The additional evidence of the cross-slab may indicate that here was the principal ecclesiastical site in [a] putative Pictish shire, maybe a monastery, or perhaps a minster-like foundation.

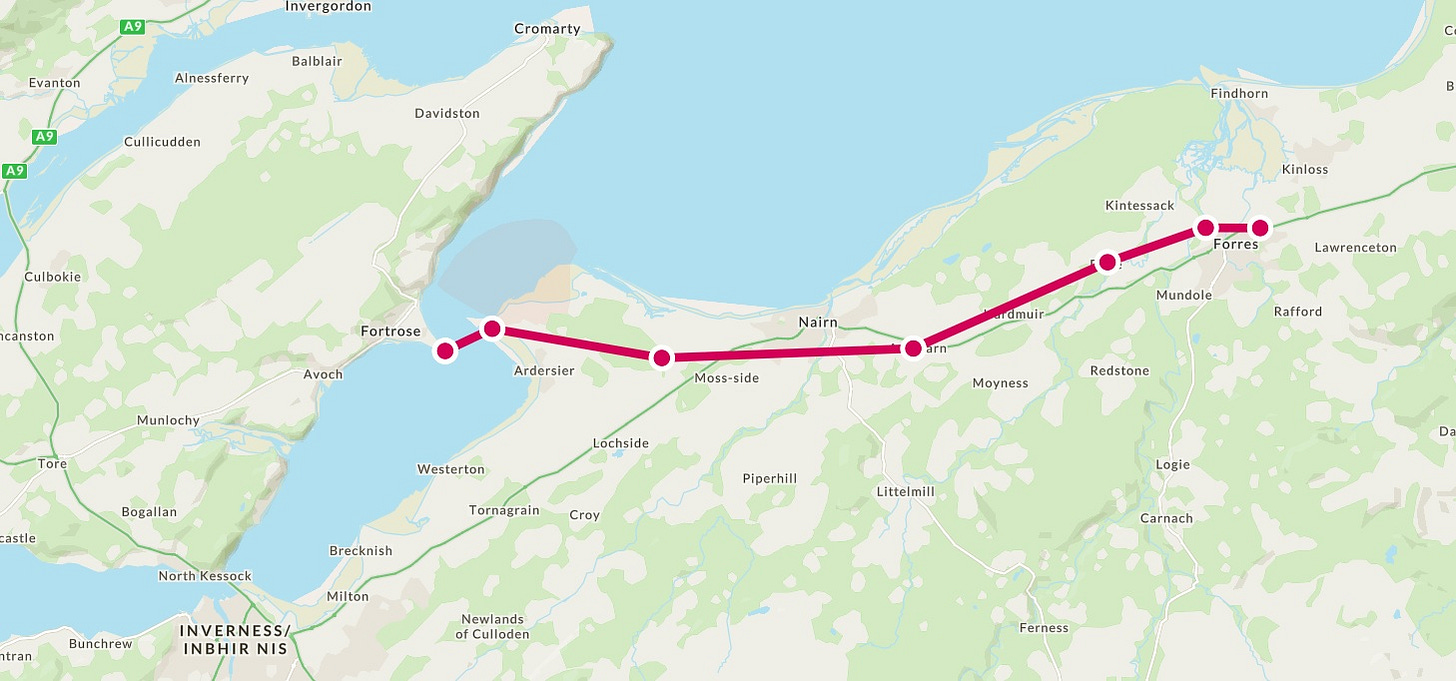

In other words, Dyke—which today is a tiny, somewhat out-of-the-way village—was an important place in the 9th century. Its church was probably one of a string of important ecclesiastical establishments along a route leading westwards along the Moray Firth coast to Ardersier, where a short boat crossing would take the traveller to Fortrose and the monastery at Rosemarkie; likely a pilgrimage destination.

For a traveller heading east, Dyke would be the last church before the ferry or ford over the River Findhorn, after which the route would take them past the Pictish cemetery at Greshop—with its huge square barrow—and onwards to the royal peninsula of Burghead and Kinneddar to the north, or to Elgin and points south.

But Dyke church of 850 AD wasn’t just a stopping point for travellers. It was also home to its clergy and a place of learning and devotion for the local populace. Someone among them was rich and connected enough to commission a handsome cross-slab, hire a professional sculptor to carve it (the work is of very high quality), and source a suitable slab of local sandstone for the purpose.

As there were sculpture workshops at the monasteries of Rosemarkie and Kinneddar, perhaps one of these supplied both sculptor and slab. And as Dyke was a thanage in the later middle ages, maybe the patron of Rodney’s Stone was also a thane, or toísech as he would have been known in Gaelic. If so, he would have been someone of fairly elevated status, perhaps even the king’s agent locally.

(I’ve always fancied that the village name of Kintessack, just north-east of Dyke, preserves the toísech title, but I’ll defer to actual place-name scholars on that one.)

Ogham inscriptions and literacy

Rodney’s Stone also has an inscription, so someone literate had to write down the words that the patron wanted to appear on it, and someone skilled in carving oghams (if not the main sculptor) had to be found to carve those letters into the stone.

Because they’re so resistant to interpretation, the ogham inscriptions of Pictland are sometimes claimed to be gibberish; the work of unsophisticated carvers imitating the kind of inscriptions they might have seen in Ireland without knowing which letters meant what.

But as many Pictish oghams do produce coherent words and phrases, and inscriptions like the one on Rodney’s Stone are clearly the work of professional carvers working in a literate, ecclesiastical milieu, that might say more about our prejudices than about the state of literacy among Pictish craftspeople. The Pictish ogham inscriptions were surely intended to communicate something; we just can’t always work out what, and the badly eroded state of many of them doesn’t help.

Erosion is the reason we can’t read any more of the long inscription on Rodney’s Stone than the one personal name, EDDARRNONN. It corresponds reasonably well to the saint’s name Ethernan, and an identical inscription also appears on the Class II ogham slab at Scoonie in Fife, undermining the theory that Pictish ogham carvers were just writing nonsense.

It would be immensely satisfying if we had any record of a dedication to St Ethernan at Dyke, but sadly all trace of the church’s original dedication has been lost, and there are no saintly place-names in the vicinity to suggest what it might have been.

(At least we don’t know it wasn’t dedicated to Ethernan!)

Symbols, monsters and hoards

Finally, the most enigmatic element of Rodney’s Stone are the Pictish motifs that appear on its reverse face: a pair of enormous fish-like creatures (sometimes called ‘S-dragons’) facing each other, a highly stylised Pictish beast (or ‘elephant’) and a double-disc and Z-rod.

The beast and the double-disc and Z-rod are very common Pictish symbols, appearing on 24 and 20 Class II slabs respectively. The debate about the meaning of the Pictish symbols continues to rumble on: there are about 30 symbols altogether, although some appear much more frequently than others, and only a small subset of them ever appear on Christian Class II slabs.

As regards the fish-like creatures, I was so taken with Katherine Forsyth’s assessment of them—or rather the motifs that sit between them—that it’s worth quoting at some length from her thesis:

Between the pair of opposed monsters there is an assortment of curvilinear motifs […]. In the centre is a large spiral disc decorated with pellets, above is an object that looks a little like a penannular brooch with expanded terminals, to the right is a crescent with pellets and to the left a circular disk decorated with a triskele, at the bottom between the monsters’ tails is another small disk decorated with a triskele.

She continues:

Each item is distinct and individual suggesting that they are intended to represent specific items, rather than merely fill the space with abstract ornament […]. If the upper item is indeed a brooch, then the crescent may also be a piece of metalwork, like the crescent-shaped silver plaque from Laws, Monifieth FOR. If the other items also represent metalwork then perhaps we have here two monsters guarding a hoard of treasure. [my emphasis]

Hoards similar to the one apparently guarded by the fish-creatures have been found buried in various places in Scotland—including one not too far from Dyke, at Croy in Inverness-shire.

Discovered in 1874 and 1875, the Croy hoard contained a penannular brooch very similar to the one depicted on Rodney’s Stone, as well as at least two Saxon coins; one of Coenwulf of Mercia (d. 821) and one of Æthelwulf of Wessex (d. 858).

If the three circular objects in the monsters’ hoard also represent coins, then the hoard depicted on the stone is very similar to the hoard found at Croy.

That’s not to say that the objects on the stone are meant to refer to the Croy hoard—even though both have been dated to the period around 850 AD. Penannular brooches and coins were very commonly deposited in treasure hoards all across Scotland.

But it does show how early medieval stone sculpture can provide glimpses of the material culture and preoccupations of the people who commissioned and carved them; all the more so when objects depicted on stones are confirmed by archaeological finds.

Treasure hoards and Viking-Age anxiety

Why might the patron of Rodney’s Stone have been keen to include an image of two creatures guarding a treasure? We can’t know for sure, but it seems likely that the stone was carved in the midst of the Viking Age; a time of relentless attacks on Pictland by sea-borne raiders that made safeguarding of precious objects a prime concern.

Many of those precious objects (although not brooches and coins, it must be said) belonged to the church, making churches—especially big ones—key targets for Viking raiders. The Pictish monastery at Portmahomack was burned to the ground in 800 AD, almost certainly in such a raid.

It was a time when any person or institution who possessed any material wealth must have been constantly on edge. Small wonder that they were often moved to bury their possessions to protect them; the hoards that have been found in modern times suggesting their owners never lived to retrieve them.

Dyke itself was likely closer to the sea in the first millennium, the great sand-dunes of Culbin to its north having been built up over centuries of storms and longshore drift.

Here on the edge of Pictland, looking out over the Moray Firth to Caithness and Sutherland—areas that would be progressively annexed and occupied by the Scandinavian earls of Orkney from the late 9th century onwards—the clergy and people of Dyke must have felt very uneasy indeed.

Conclusion

My plan with this blog was to “just start writing and see if it takes me (and you) anywhere interesting” and I’m actually very pleased with the result.

I didn’t think I’d come up with anything that wasn’t already known about Rodney’s Stone – but Katherine Forsyth’s comment about monsters guarding a hoard of treasure opened up some new (to me) thoughts about material wealth and anxiety in the Viking age. I also did a bit of digging to find out more about Rev. John McEwen of Dyke, and hopefully restored his reputation a bit.

So I’m pleased, and I hope you’ve found something to enjoy and think about here too. As always, I’d love to hear any thoughts you may have in the comments.

References

M. Carver et al, Portmahomack on Tarbat Ness (2019)

K. Forsyth, Naming, forgetting, remembering, imagining: The name-scapes of Iona’s stone sculpture (Paper given at the Worked In Stone conference, September 2022)

K. Forsyth, The Ogham Inscriptions of Scotland: An Edited Corpus (1996)

S. Foster et al, A Fragmented Masterpiece: Recovering the biography of the Hilton of Cadboll Pictish cross-slab (2021)

T. Lauder, An Account of the Great Floods of August 1829, in the Province of Moray, and Adjoining Districts (1830)

A. Maldonado, The Croy Hoard (online lecture for North of Scotland Archaeological Society, 2020)

H. McKay, Pictish Symbols: Lists and Distribution Part One (2019)

R. McKim, Henry McEwen of Glasgow: A Forgotten Astronomer? (2011)

J. Mitchell et al, Monumental cemeteries of Pictland: Excavation and dating evidence from Greshop, Moray, and Bankhead of Kinloch, Perthshire (2020)

E. Okasha, Why include an inscription on an Anglo-Saxon sculptured stone monument? (Paper given at the Worked In Stone conference, September 2022)

A. Ross, Land Assessment and Lordship in Medieval Northern Scotland (2015)

H. W. Young, Discovery of an Ancient Burial Place and a Symbol-Bearing Slab at Easterton of Roseisle (in The Reliquary and Illustrated Archaeologist, July 1895)

Thanks for ferreting out that info about the Rev MacEwan - it does make a difference, I think.

I love discovering your writing--as a former graduate student in Glasgow in the late 90s, it's so lovely to return to thinking about the Picts, the stones and that archaeology. Love these deep dives into the history of the stones.