Rossia, Rigmonath, Bellethor: Early Gaelic settlements in Pictland?

In which I investigate three intriguing places named in the tenth-century Life of St Cathroe.

[UPDATE 12/06/25 Many thanks to all who have commented in various places on my thoughts here. The consensus among toponymists is that 'Rathinveramon' is likely to refer to a specific River Almond and not a generic river confluence - so Inveralmond in Perth is most likely the place meant (as the other River Almond is outwith Pictland). So I can strike the thought off the list that it might refer to the fort of Caisteal mac Túathal on Drummond Hill. And having looked more closely at Dull and at some of the sculpture found there, it looks like I can't dismiss it so readily in favour of Fortingall as the possible location of Cinnbelachoir/Bellethor. So back to the drawing board for me on some of these points!]

[UPDATE 18/06/25 Thanks very much indeed to Bill Patterson, who has pointed out that the name 'Chorischii' (given to the band of Greek-speakers who conquer Ireland and Scotland in the Vita Cathroe's introductory legend) is remarkably similar to that of the Cherusci, a Germanic people encountered by Julius Caesar during his Gallic Wars. This seems to be the name meant, as the author of the Vita places this legendary action in the first century BC. He may have had access to Caesar's text.]

I’m sorry I haven’t posted for a little while. I’ve been super-busy with client work, writing my first PhD submission, and preparing for—and giving—a lecture to the Archaeology Scotland summer school, held last month in a gloriously sunny Strathpeffer.

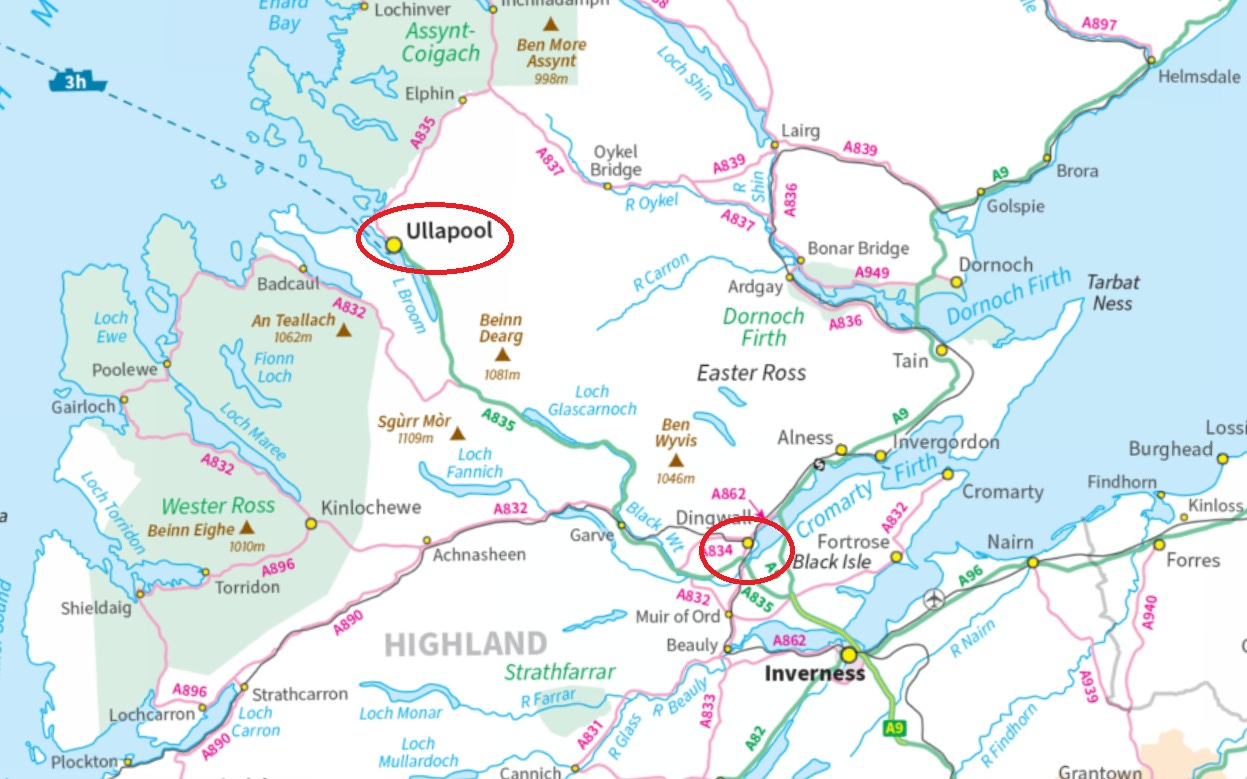

My lecture topic was the early church in Easter Ross and the Black Isle, and I’m going to be revisiting it in an online lecture for Rosemarkie’s Groam House Museum in August. So if it sounds like your thing, keep an eye out for the booking link.

For this blog, I want to dig into one of the few scraps of textual evidence that we have for the early church in the Firthlands (and elsewhere).

I’ve been intrigued by some apparent similarities between this text and the distribution of a certain place-name element in eastern Scotland, and I want to see if they might be connected.

I’m not sure as I start writing where I’m going to end up, but let’s give it a go.

The tenth-century Life of St Cathroe

The text in question was written in the late tenth century, perhaps around 990, in or near Metz in north-east France, which at the time was in the contested former kingdom of Lotharingia (Lorraine).

It’s the Vita (legend) of a saint named Cathroe, abbot of the monastery of St Félix in Metz, who had recently died. Its author was a monk named Reimannus or Ousmannus who hadn’t personally known Cathroe, but who had gathered information about him from people who had.

The Vita Cathroe tells us that its subject hailed originally from Scotland, and was apparently of high or royal birth.1 He was educated at the monastery of Armagh in Ireland, and later set out on a permanent pilgrimage. This pilgrimage took him and (a symbolic) 12 companions to the continent, where he eventually ended his days in Metz.

An odd version of an Irish origin legend

None of this is particularly relevant to my enquiry. The crucial thing for me is that this author prefaced his Vita with a unique and odd version of an Irish origin legend.

In it, he describes how Ireland was conquered in the first century BC (an anachronistic timeframe, as we’ll see) by a group of Greek-speakers from Asia Minor calling themselves ‘Chorischii’. This name isn’t known otherwise, and the author of the Vita Cathroe seems to have invented it.2

Having defeated the local Picts (who live in Ireland in this version of the legend) and taken control of a string of places including Clonmacnoise, Kildare, Armagh and Bangor, the Chorischii cross the North Channel and set about colonising the country we know as Scotland:

Fluxerunt quot anni, et mare sibi proximum transfretantes Euam insulam, quae nunc Iona dicitur, repleuerunt.

Many years passed until, crossing the sea nearest to them, they occupied the island of Euea, now called Iona.3

The author then tells us that:

Nec satis, post pelagus Britanniae contiguum perlegentes, per Rosim amnem, Rossiam regionem manserunt: Rigmonath quoque Bellethor urbes, a se procul positas, petentes, possessuri vicerunt.

Not yet satisfied, after surveying the nearby sea of Britain, they settled along the River Rosis in the region of Rossia. Heading for the towns of Rigmonath and Bellethor, which are not far from one another, they took possession of them.

The aim of this legend appears to be to place Cathroe, a Gaelic-speaking cleric from Scotland, in a historical context. That seems clear from the fact that the ‘Chorischii’ infiltrate Pictland from a bridgehead established in the major Gaelic monasteries of Ireland and Iona.

My interest is in the three places said to have been occupied by the Chorischii: Rossia, Rigmonath and Bellethor. The first two are identifiable, but the third is uncertain. My hunch is that place-name evidence of a different kind can shed light on the location of Bellethor.

But first, let’s look at each place in turn.

The regio of Rossia—modern-day Easter Ross

Scholars agree that Rossia is Easter Ross in northern Scotland. According to the Vita, the Chorischii get there from Iona via a river named Rosis, along which they also settle.

No river of that name exists today, but both the nineteenth-century historian W.F. Skene and the twentieth-century toponymist (and Easter Ross native) William J. Watson identified it as the Rasay, the old name for the river now named Blackwater.4

The Blackwater rises in mid-Ross and flows past Garve and Contin into the River Conon, which then flows into the Cromarty Firth and out into the Moray Firth. It forms part of a natural route from the west coast to Easter Ross—the route now taken by the A835 Ullapool to Dingwall road.

This route, south-eastwards from Loch Broom, appears to be the one taken by the Chorischii into Rossia. It’s not the most efficient way to get from Iona to Easter Ross—that would be up the Great Glen—but efficiency was perhaps not the author’s concern.

Interestingly, unlike most of the other places the Chorischii occupy, Rossia is described as a region (regio) rather than an urbs, civitas or other type of settlement. This is despite the existence of an important monastery at Rosemarkie on the Black Isle that was probably founded before 700. I’ll come back to this in my conclusion.

(For reasons outlined in this post, I think the Tarbat peninsula, with its major monastery at Portmahomack, was part of Moray in the late first millennium AD, rather than part of Ross.)

The urbs of Rigmonath—modern-day St Andrews

The next name, Rigmonath, is clearly a truncated version of the oldest recorded name for St Andrews, Cennrígmonaid.

In Gaelic the whole name means ‘head’ or ‘end’ (ceann) of the king’s (ríg) muir or upland (monadh). Rigmonath on its own, then, could be translated as ‘Kingsmuir’.

St Andrews had a monastery that was founded before 747, since the Annals of Ulster record the death of its abbot, Túathalan, in that year.

It also claimed to have—and perhaps did have—relics of St Andrew, making it an international pilgrimage destination by the tenth century.5 So it’s not surprising to see it appear in the Vita as a major monastery of eastern Scotland.

The urbs of Bellethor—an elusive location

The tricky name is Bellethor. This appears to be the same place as the Cinnbelathoír or Cinnbelachoir named in the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba (CKA), a late tenth-century list of reign-lengths and brief notes for twelve kings of Picts—who after 900 were called kings of Alba—from Cináed mac Ailpín (d.858) to Cináed mac Maíl Choluim (d.995).6

Of Domnall, brother of Cináed mac Ailpín (d.862), CKA tells us that:

Obíít in palacio Cinnbelathoír idus Aprilis.

He died in the palace of Cinnbelathoír on the Ides of April.

However, another set of king-lists with origins in the early twelfth century say that Domnall mac Ailpín died at a place called Rathinveramon.7 This is usually identified as Inveralmond, where the River Almond meets the Tay just north of Perth.

Ráth means ‘fort’ in Old Irish, and it’s sometimes been proposed that Rathinveramon was the old Roman military fort of Bertha, repurposed as a royal residence by the early mac Alpin kings. (However, an excavation at Bertha in 1973 found no evidence of early medieval re-occupation.)8

Other medieval chronicles seem to place Domnall’s death elsewhere. The eleventh-century Prophecy of Berchán says he died ós Loch Adhbha, which Alan Orr Anderson translated as ‘above Loch Awe’, in Argyll.9 The twelfth-century Verse Chronicle says he died at Scone, and this was repeated by the fourteenth-century chronicler John of Fordun.10

Was Bellethor at Scone?

While the actual death-place is elusive, scholars often assume that Cinnbelathoir and Rathinveramon were the same place, or at least in the same area. The fact that Fordun cited Scone, just across the Tay from Inveralmond, means it’s often identified as Cinnbelathoir.

One problem with that, though, is that CKA elsewhere mentions Scone by that name. For the year 906, it says (my emphasis):

In .vi. anno Constantínus rex et Cellachus episcopus leges disciplínasque fidei atque íura ecclesiarum ewangeliorumque pariter cum Scottis in colle credulitatis prope regali cívítati Scoan.

In the sixth year [of his reign] King Constantine and Bishop Cellach vowed—on the Hill of Belief near the royal civitas of Scone, after the fashion of the Gaels—to keep the laws and disciplines of the faith and the rights of the church and the Gospels.11

Another issue is that the name Cinnbelathoir seems to mean ‘head’ or ‘end’ (ceann) of the mountain pass (bealach). That’s not a great description of Scone’s lowland position by the Tay.

Three other possibilities: Cramond, Ballater, Taymouth

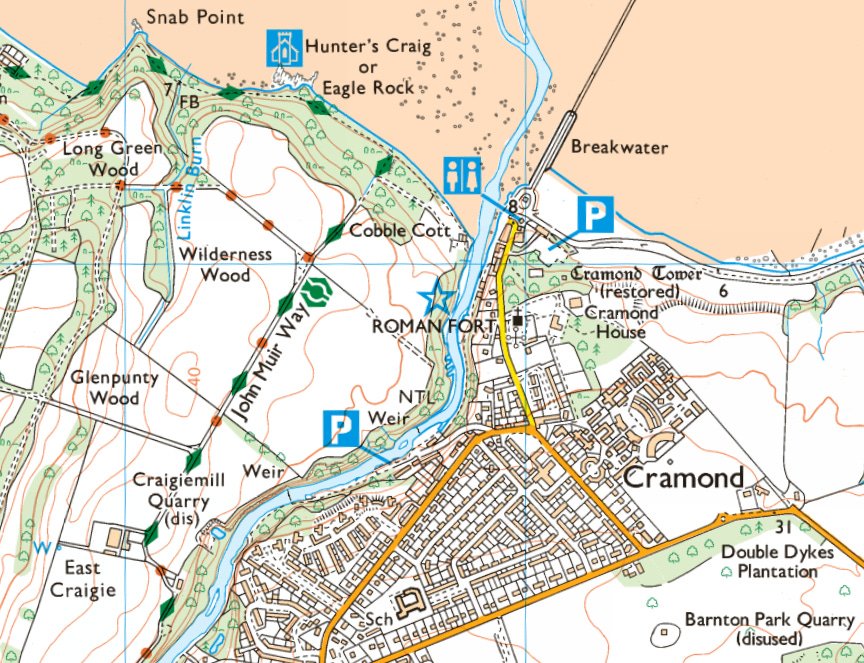

So the idea of Cinnbelathoir as Scone is a bit unsatisfactory, and this has led historians to propose three other possible locations for Domnall mac Ailpín’s death-place: Cramond near Edinburgh, Ballater on Deeside, and Taymouth on Loch Tay.

The argument for Cramond rests on the name Rathinveramon meaning ‘fort at the mouth of the Almond’. Cramond sits at the mouth of another River Almond, which falls into the Firth of Forth, and there is another Roman fort here.

Technically, then, it could be a contender, but, as Alex Woolf noted in 2007, the historical context doesn’t fit.12 Cramond was almost certainly in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria when Domnall died in 862, so it’s hard to imagine he had a royal residence here.

Ballater and its problems

I’ve only seen Ballater suggested in footnotes. One appears in volume 3 of Dr Simon Taylor’s epic five-volume The Place-Names of Fife, and simply says:

It is not known where [Bellethor] is. It may be Ballater on the Dee.13

The other is in a chapter by James Fraser on the cult of St Andrew, which reads:

Bellethor must signify the palacium Cinnbelachoir where Domnall mac Ailpín died in April 862. It has been suggested that this palatial monastery be placed at the head of the Pass of Ballater on Deeside, and identified with Tullich, where the church bore a dedication to St Nechtan, probably a Pictish abbot who died in 678.14

Ballater does mean ‘place of the mountain pass’, making it a nice match for Bellethor. But again, the context doesn’t really fit. The Vita seems to be naming early and important Gaelic foundations, and, as Fraser notes, Tullich is closely linked to a Pictish saint, Nechtan.

Excavation has also shown it was a comparatively small foundation.15 It’s hard to see why it would be listed while early Gaelic monasteries like Abernethy and Applecross were left out.

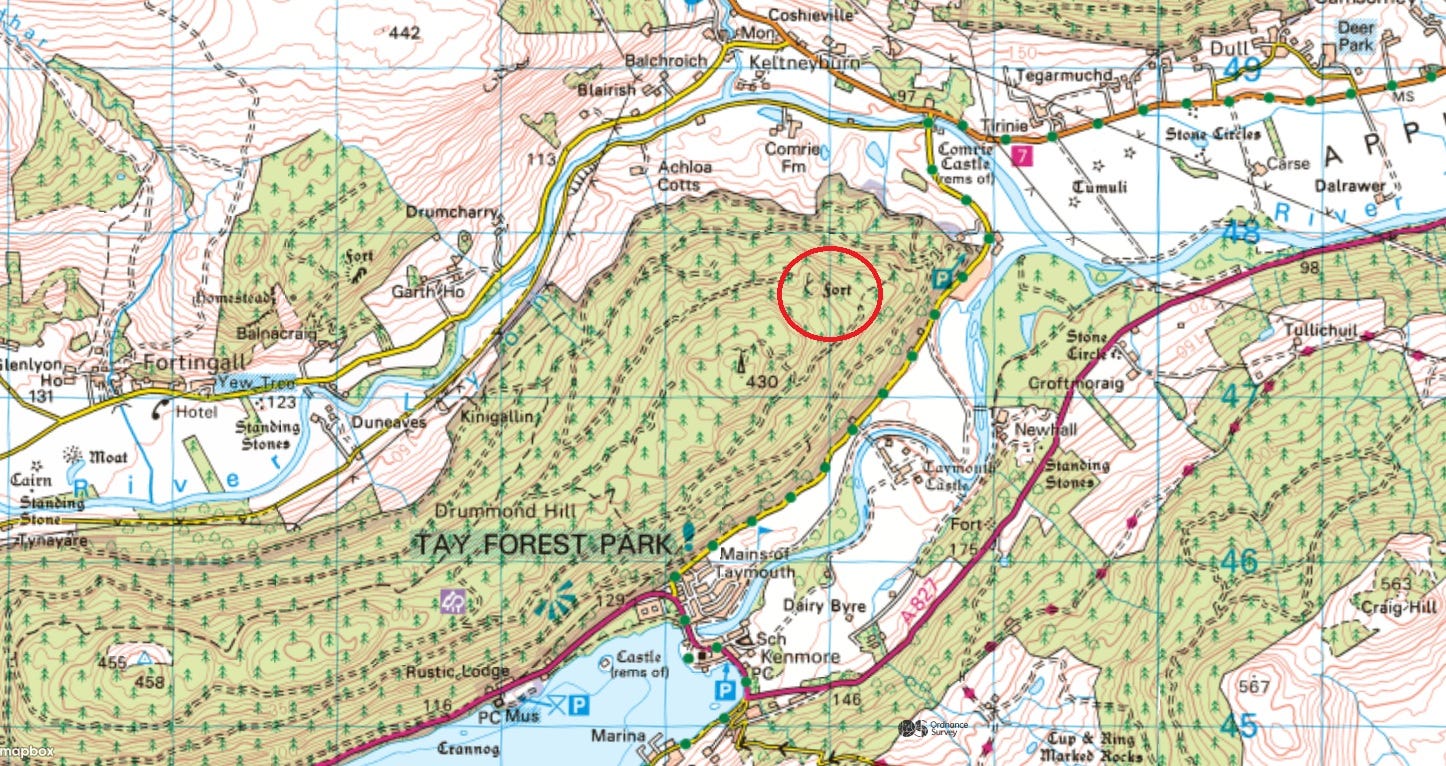

Taymouth: a highland location for Bellethor?

The third alternative, Taymouth on Loch Tay, was briefly suggested by Professor Ted Cowan in a 1981 article on the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba (then known as the Scottish Chronicle).16

Having noted that Rathinveramon is probably Inveralmond, and acknowledging that CKA’s Cinnbelathoir is likely the same place as the Vita’s Bellethor, he wrote:

Though its occurrence is much later, Taymouth is called Bealach in Gaelic and Taymouth Castle is Castle Bhealaich.

However, he then immediately added an apparent non sequitur:

Cinn Belachoir might therefore apply to some site in the vicinity of Perth though the precise location remains unidentified.

But Taymouth isn’t really ‘in the vicinity of Perth’. It’s 40-ish miles to the north-west, at the eastern end of Loch Tay. It seems that Cowan, unable to reconcile lowland Inveralmond with highland Taymouth, fell back on a Perth-adjacent location as being most likely.

But I actually think his suggestion of Taymouth was spot on. Not because of its Gaelic name Bealach, although that is interesting and relevant. It’s because of a completely different body of evidence: the distribution of the Gaelic place-name element cill- in Pictish Scotland.

Cill- names and the eastward spread of the Gaelic church

As long ago as 1976, the toponymist W.F.H. Nicolaisen proposed that place-names with the element cill, meaning ‘church’ or ‘burial ground’, were indicative of:

The spread of Irish ecclesiastical influence within a Gaelic-speaking context, not later than the last few decades of the eighth century, perhaps earlier.17

In other words, cill- names (usually in the form Kil + saint’s name, like Kilmartin) were clues to the way the Gaelic church spread, in the eighth century, from its heartland in the kingdom of Dál Riata (Argyll) into other parts of early medieval Scotland.

Nicolaisen was the first to use distribution maps to analyse historical processes through the prism of place-names, and his method inspired a new wave of Scottish linguists and historians.

In 1996, Simon Taylor considerably refined and improved upon Nicolaisen’s mapping of cill- names in eastern Scotland. In the process, he identified three distinct clusters: one in Easter Ross, one in East Fife, and one in Atholl, in highland Perthshire.

Taking his cue from Nicolaisen, Taylor proposed that these clusters reflected the presence in each area of early and influential Gaelic monasteries. For the East Fife cluster, he noted:

[I]t would appear that they were radiating out from some important early church establishment, with Scottish or Irish connections and high political standing.

Noting that its first-recorded abbot had a Gaelic name, Túathalan (d. 747), he proposed that:

The obvious candidate… was Kinrymonth (Cennrígmonaid), later known as St Andrews.

For the cill- cluster in Easter Ross, he wrote:

[I]t is tempting to see them in conjunction with that famous, if shadowy, figure Curadán-Boniface [fl. 697], bishop of Rosemarkie.

And for the Highland Perthshire cluster, he wrote:

Atholl lies at the eastern end of one of the few major crossing points of Druim Alban, by Strathfillan and Glen Dochart to Loch Tay. The name ‘Atholl’ alone, which means New Ireland and is first recorded in 739, suggests major early settlement from the West.

So we have three places cited in a late tenth-century Vita as having been occupied by early Gaelic settlers, and three clusters of cill- names in Pictland that seem to indicate hotspots of christian Gaelic settlement in the first half of the eighth century.

The Rossia of the Vita aligns to the cill- cluster in Easter Ross, and Rigmonath aligns to the cluster around St Andrews. Should we be seeking Bellethor in Atholl?

Reasons to place Bellethor in Atholl

In fact, even without the link just discussed, there’s a good case to be made for placing both the Bellethor of the Vita, and the Cinnbelachoir where Domnall mac Ailpín died in 862, in Atholl.

As noted earlier, both names contain the Gaelic word bealach (Old Irish belach), meaning ‘mountain pass’. As Simon Taylor noted above, Atholl lies at the eastern end of an important pass that led from early medieval Dál Riata into Pictland, via Glen Dochart and Loch Tay.

And while Rathinveramon seems to denote a place at the mouth of a River Almond, there are other ways to interpret it. Inver can mean ‘confluence’ as well as ‘mouth’, and both of the rivers Almond are so called because Almond, or amon, means ‘river’. If we strip out proper nouns, Rathinveramon can be interpreted as ‘fort of the river confluence’.

Then there’s the Prophecy of Berchán’s claim that Domnall died ós Loch Adhbha, translated by Alan Anderson as ‘above Loch Awe’. But adhbha in Old Irish means ‘dwelling-place’. That means Loch Adhbha could be ‘loch of the dwelling-place’, again opening up other possibilities.18

Taken together, these names might prompt us to look for a fort located at the head of a mountain pass, at a river confluence and above a loch. And there is a fort in Atholl that meets this description exactly: Caisteal mac Túathal on Drummond Hill at the head foot19 of Loch Tay.

A good site for an early medieval royal stronghold

The location of Caisteal mac Túathal at the end of a loch, on a major route between Pictland and Dál Riata, recalls that of Dundurn at the head of Loch Earn, where another ninth-century king, Giric (d.889), had his stronghold, and where many early medieval artefacts have been found.

Gordon Noble and Nick Evans also note its similarity to another major early medieval hillfort, the King’s Seat at Dunkeld:

[N]ear to Fortingall and Dull, at the confluence of the Tay and Lyon, is the striking hillfort of Castel mac Túathal. [It] is morphologically similar to the King’s Seat, Dunkeld, and is an excellent candidate for an early medieval fort.20

So to my mind, there’s a good chance that the unexcavated Caisteal mac Túathal is the fort of Rathinveramon, home base of Domnall mac Ailpín, king of Picts from 858 to 862.

Locating Bellethor and Cinnbelachoir

But where should we locate the palacio Cinnbelachoir where Domnall is also said to have died, and the urbs of Bellethor, which the Vita Cathroe suggests was a significant Gaelic monastery?

The term palacio suggests somewhere low-lying. CKA tells us that Cináed mac Ailpín, Domnall’s elder brother, died in the palacio of Forteviot, which is situated on the valley floor in Strathearn. If Bellethor was a monastery, it’s also likely to have been in a lowland location.

And we don’t have to look far to find a suitable candidate. As Noble and Evans noted above, there are two early ecclesiastical sites within a couple of miles of Castel mac Túathal, at Fortingall in Glen Lyon and Dull in Strathtay.

The case for Fortingall

Of the two, Fortingall is the better fit for Bellethor. A 2011 excavation by Dr Oliver O’Grady revealed that it was a large monastic site, with a double vallum enclosing some 4 hectares.21 Radiocarbon dates suggest the vallum was dug in the seventh century.

Based on these findings, Noble et al count Fortingall, along with Portmahomack and Kinneddar, as one of the largest-known early monastic sites in Pictland. They comment that:

These larger ecclesiastical sites must have been densely populated centres and appear to have been associated with extensive production, trade and conspicuous consumption.22

Fortingall, then, would easily fit the label of urbs (‘settlement’) given to Bellethor in the Vita Cathroe. And it sits right at the centre of the cluster of cill- names that Simon Taylor identified in Atholl.

Other evidence also supports an early Gaelic pedigree for Fortingall and its surrounds. For one thing, the area has a high density of church dedications and place-names referencing eighth-century Iona clerics: seven for Adomnán (d.704) and three for Coéti, bishop of Iona (d.712).23

Fortingall church also had a quadrangular iron hand-bell (sadly lost since it was stolen in 2017) of a kind strongly associated with the early Gaelic church.24 It’s one of three such bells known from Glen Lyon, marking this area out as a hotspot of early Gaelic ecclesiastical activity.

Even the name Atholl itself, as we saw earlier, means ‘new Ireland’. It’s first recorded in an annal of 739, probably written on Iona, recording strife between two Pictish kings:

Talorggan m. Drostain, rex Athfoitle, dimersus est, .i. la Oengus.

Talorggan son of Drostan, king of Atholl, was drowned, that is, by Oengus.25

(Although, as Professor Thomas Clancy has noted, it’s unclear who gave the area this surely-provocative name, and who used it.26 Did Pictish kings of Atholl really dub themselves ‘king of New Ireland’?)

The ‘church of the fortress’—with its own royal hall?

The name Fortingall is obviously not the same as Bellethor, but this needn’t be a huge obstacle, as the place may have had two names.

As noted previously, Bellethor means the place of the mountain pass, which could describe Fortingall’s location at the western entrance into Pictland. The second element of Fortingall is Gaelic cill , ‘church’, and W.J. Watson saw its first element as a Pictish word cognate with Welsh gwerthyr, ‘fortress’.27 The name Fortingall, the ‘fortress church’, thus describes the church itself.

(A similar example might be Beauly near Inverness. That name means ‘beautiful place’, but its other name, A’ Mhannachain, means ‘the monastery’.)

Watson thought the fort in question was An Dún Geal, a small fort behind Fortingall. But the name Fortingall might equally mean it was the church associated with the hillfort I’m proposing as the royal stronghold of Rathinveramon: Caisteal mac Túathal on nearby Drummond Hill.

We know that in the ninth century, Pictish kings kept halls within large church-settlements. A scrap of surviving text tells us that King Uurad (d. 842) had a royal hall in the church-settlement of Meigle.28 Perhaps kings of Atholl also kept a royal hall within the monastery of Fortingall.

In which case, we might see the area around the head foot of Loch Tay as a ‘polyfocal central place’ in the eighth to tenth centuries, with the royal fortress of Rathinveramon high on Drummond Hill, and a lowland royal palace of Cinnbelachoir within the monastic complex of Bellethor—also known as Fortingall, the church of the fortress.

An Atholl location for Bellethor: but how did Reimannus know?

Having puzzled this through, I’m pleased with the conclusion I’ve come to. I think there’s a good argument that the Bellethor of the Vita Cathroe and the Cinnbelachoir of CKA both refer to Fortingall, and that the Rathinveramon of the twelfth-century king-lists was Caisteal mac Túathal.

Even more interesting is the fact that the three places named in the Vita Cathroe seem to reflect a late tenth-century understanding of how the Gaelic church moved into Pictland. And intriguingly, that understanding seems to exactly mirror our own current view of that process.

Our view is based on W.F.H. Nicolaisen and Simon Taylor’s work on the distribution of the place-name element cill. But where did Reimannus, the author of the Vita Cathroe, get his view?

Was it known among Scottish monks in late tenth-century Metz that Ross, East Fife and Atholl had been early eighth-century centres of Gaelic ecclesiasticism? Or had they, like us, formed that view from noticing indicators like clusters of cill- names?

Conclusion: an insight into tenth-century antiquarianism?

One hint towards the second option is that, as I noted at the start, Rigmonath and Bellethor are described in the Vita as urbs, referring to the monastic settlement itself. Rossia, by contrast, is called a regio (region).

Was there something about the monastery of Rosemarkie that made Reimannus’s informants think it wasn’t originally a Gaelic establishment, even though it was surrounded by cill- names and was surely Gaelic-speaking by the late tenth century?

And could that thing have been the massive Pictish symbol-bearing cross-slab that stood in or near the the original monastery?

It’s notable that neither St Andrews nor Fortingall have sculpture with Pictish symbols. If it was the cross-slab that made Rosemarkie feel different, we may have an insight into how symbol-bearing slabs were viewed in the tenth century: then as now, as indicators of a Pictish, rather than Gaelic, church foundation.

As ever, thank you for reading, and I look forward to any comments or feedback.

David Dumville, ‘St Cathroe of Metz and the hagiography of exoticism’, in Studies in Irish Hagiography: Saints and Scholars, edited by John Carey, Máire Herbert and Pádraig Ó Riain (Four Courts Press, 2001), 176-7.

Thanks very much indeed to Bill Patterson, who has pointed out that the name 'Chorischii' is remarkably similar to that of the Cherusci, a Germanic people encountered by Julius Caesar during his Gallic Wars. This seems to be the name meant, as the author of the Vita places this legendary action in the first century BC. He may have had access to Caesar's text.

Translation by Pádraig Ó Riain, ‘The Metz version of Lebor Gabála Érenn’, in Lebor Gabála Érenn: Textual History and Pseudohistory, edited by John Carey (Irish Texts Society, 2009), 41.

William J. Watson, Place-Names of Ross and Cromarty (Northern Counties Printing and Publishing, 1904), xxi.

Simon Taylor, ‘From Cinrigh Monai to civitas Sancti Andree: a star is born’, in Medieval St Andrews: Church, Cult, City, edited by Michael Brown and Katie Stevenson (Boydell, 2017), 23.

See Alex Woolf, From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070 (Edinburgh University Press, 2007), 88–93.

Marjorie O. Anderson, Kings and Kingship in Early Scotland, 2017 reprint (Birlinn, 2017), 267, 274, 284.

Helen Adamson and Dennis B. Gallagher, ‘The Roman fort at Bertha, the 1973 excavation’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 116 (1987): 203. Thanks to Rod McCullagh for pointing out that this excavation was limited in scope and doesn't rule out early medieval re-occupation.

Alan Orr Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to A.D. 1286, vol. 1 (Oliver & Boyd, 1922), 292.

Anderson, Early Sources, 291.

Translation by Woolf, Pictland to Alba, 136.

See Woolf, Pictland to Alba, 104.

Simon Taylor with Gilbert Márkus, The Place-Names of Fife, vol. 3 (Shaun Tyas, 2009), 408.

James Fraser, ‘Rochester, Hexham and Cennrígmonaid: The movements of St Andrew in Britain, 604–747’, in Saints' Cults in the Celtic World, edited by Steven Boardman, John Reuben Davies and Eila Williamson (Boydell and Brewer, 2009), 16.

Gordon Noble, Laura Gonzalez Bojaca, Robin Worsman and James O’Driscoll, ‘Defining the sanctissimus: the early medieval church enclosures of Pictland’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 153 (2024): 121-140.

Edward J. Cowan, ‘The Scottish Chronicle in the Poppleton manuscript’, The Innes Review 32:1 (1981): 3–21.

W.F.H. Nicolaisen, Scottish Place-Names: Their Study and Significance (B.T. Batsford, 1986), 130.

As I’m about to suggest that Loch Adhbha is Loch Tay, it’s interesting to think that adhbha might refer to the many crannogs (artificial lake dwellings) that have been found in this loch.

(Thanks to Alan James for the correction!)

Gordon Noble and Nicholas Evans, Picts: Scourge of Rome, Rulers of the North (Birlinn, 2022), 182.

Noble et al, ‘Defining the sanctissimus’, 127.

Noble et al, ‘Defining the sanctissimus’, 130.

Simon Taylor, ‘Iona abbots in Scottish place-names’, in Spes Scotorum, Hope of Scots: Saint Columba, Iona and Scotland, edited by Dauvit Broun and Thomas Owen Clancy (T&T Clark, 1999), 58–59; 68–69.

Cormac Bourke, ‘The hand-bells of the early Scottish church’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 113 (1984), 466.

Annals of Ulster s.a. 739.7.

Thomas Owen Clancy, ‘Atholl, Banff, Earn and Elgin: “New Irelands” in the east revisited’, in Bile ós Chrannaibh: A Festschrift for Professor William Gillies, edited by W. McLeod, A. Burnyeat, D.U. Stiubhart, T.O. Clancy and R. Ó Maolalaigh (Clann Tuirc, 2010), 88.

William J. Watson, The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (Blackwood & Sons, 1926), 69.

Woolf, Pictland to Alba, 98.

As you say, a pleasing conclusion, Fiona - brilliant. And as I was reading the closing paragraphs I found myself wondering what exactly is ceann meant to tell us (especially where beul 'mouth' might be expected eg with bealach), so it's exciting that you (and Alex) are on the case already :)

Very good article as ever, articulate and stimulating.

Slightly disappointed that you don’t give Dull more consideration as the likely monastic settlement associated with Bellethor though this is just based on a personal preference for the atmosphere of Dull over Fortingall!

There is more archaeological evidence for Fortingall being a significant site at the correct period but that may be due to a lack of study of Dull. Just saying let’s not dismiss it