The Achareidh fragment: antiquarian curio or evidence of a lost Pictish site?

In which I try to puzzle out the origins of a cross-slab fragment found near Nairn in 1890

I’ve been away from the blog for a while, as my time has been somewhat taken up with family matters, the long-awaited start of my Medieval Studies MA, and a pile-up of freelance writing work.

But that doesn’t mean I’ve been entirely idle in my quest to get to grips with early medieval Moray.

In fact a few weeks ago, I found myself wondering about a small piece of sculptured stone that was last officially seen in 1978, and which nobody seems to have given much thought to since.

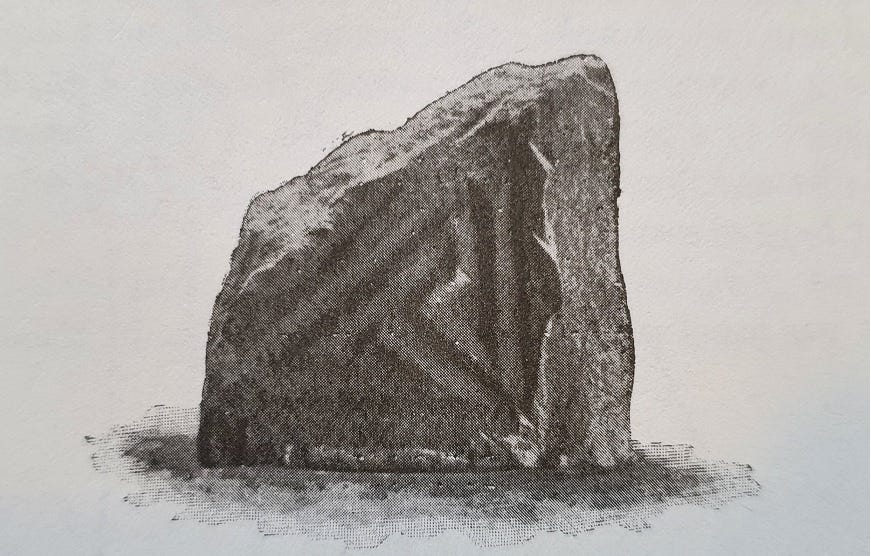

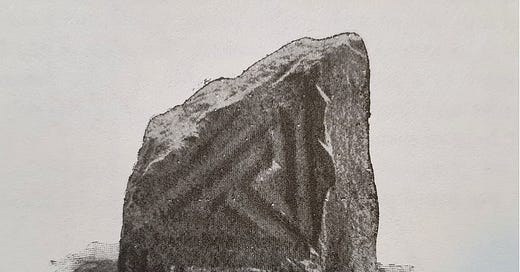

This is the Achareidh fragment, a broken piece of sandstone carved very finely with key-pattern, a style of ornament used extensively in the 8th and 9th centuries on ecclesiastical stone sculpture.

According to J. Romilly Allen’s 1903 survey The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland, it was dug up in 1891, in the grounds of Achareidh House, just to the west of Nairn:

The sculptured stone was found in 1891 by Colonel Clarke’s workmen in digging a hole for the post of a fence on the highest point of ground behind his house. It is a fragment of an upright cross-slab of sandstone, sculptured in relief on one face.

There’s a slight question mark over that date, as local historian George Bain, in his History of Nairnshire (1893), put it a year earlier:

In 1890 a portion of a slab was dug up at Achareidh, near Nairn, bearing carvings of the fretwork pattern similar to what appears with such perfection on the Rosemarkie stone. It is evidently the corner of a cross-bearing slab with raised border.

(It doesn’t really matter whether it was found in 1890 or 1891, but I might be inclined to give Bain the edge on the date, as he was writing closer to the time of discovery and his knowledge was local.)

To my knowledge, these two accounts represent the sum total of what’s known about this fragment—apart from one sparse entry in Canmore, Historic Environment Scotland’s online database of historical sites and archaeological finds.

It cites a survey conducted in 1978 by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS):

A small unweathered fragment of an Early Christian/Pictish class III stone bearing a key pattern on one face is preserved at Achareidh House. The stone was found in 1891 just to the NW of the house.

A forgotten fragment of Pictish sculpture

Given the fact that it’s so small, that it hasn’t been seen since 1978, and that Nairnshire doesn’t seem to be on the radar of any university archaeology departments, it’s unsurprising that this fragment has been more or less completely overlooked.1

Plus, on the face of it, it doesn’t offer much to excite the Pictophile: it doesn’t have any Pictish symbols on it, it’s not associated with a known Pictish ecclesiastical site, and there are no traces of any inscriptions. It could easily be dismissed as a stray find.

But I wondered if it had more going for it than that—particularly in the context of the wider geographical area, and what we know about other sites in that area.

Two things struck me especially: the quality of the carving, and the fact that its presence at Achareidh could indicate a lost Pictish ecclesiastical site there. So this blog is my attempt to put the fragment into some kind of context.

A high-quality piece of key-pattern carving

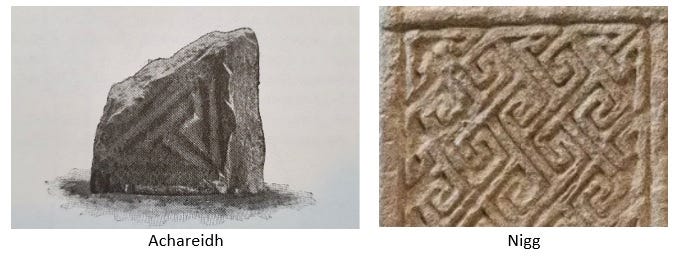

First, the quality of the carving. George Bain was spot-on when he observed that the key pattern on this fragment is “similar to what appears with such perfection on the Rosemarkie stone.”

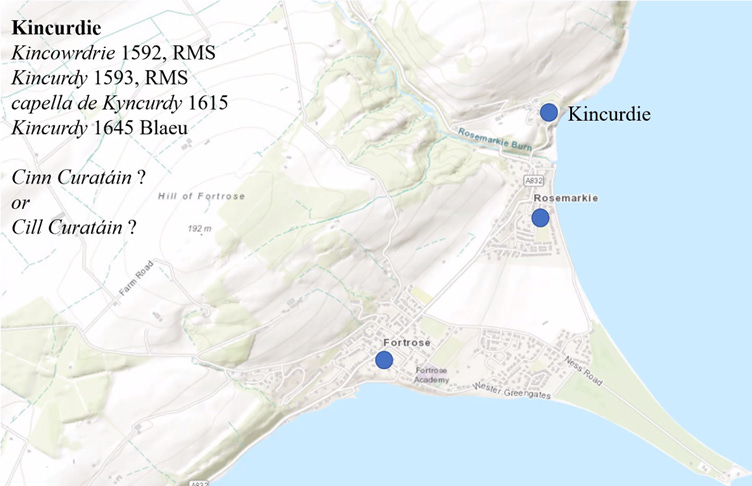

Rosemarkie, just a few miles west of Achareidh, but separated from it by the Moray Firth, was the site of a major Pictish church settlement that was almost certainly in place by 697 AD. We know this because a bishop persistently associated with Rosemarkie, Curetán, appears as a signatory to a legal document known as the Cáin Adomnaín, which passed into law in that year at the Synod of Birr.

There’s also ample material evidence for an important ecclesiastical site at Rosemarkie, including numerous fragments of stone sculpture of an extremely high quality. And in a recent lecture for the Groam House Museum, Gilbert Márkus of Glasgow University highlighted a number of place-names around the village that hint at quite a wide ecclesiastical domain—like Kincurdie, which probably preserves Curetán’s name, and Corslet, which is likely Gaelic crois-leathad, or slope with a cross.

Many of the sculpture fragments found at Rosemarkie make use of a key-pattern design like that of the Achareidh fragment. And while key pattern was widely used throughout Pictland, the carving from Rosemarkie is especially notable.

In fact Dr Cynthia Thickpenny, an expert in Pictish pattern ornament, has identified Rosemarkie as the base of an exceptionally gifted sculptor she calls “the master carver of Northern Pictland.”

In 2018, she published an important paper demonstrating that this sculptor—or team of sculptors—carried out work not just at Rosemarkie, but also at Nigg on the Tarbat pensinsula and at the Pictish monastery of Applecross in Wester Ross, on the west coast of Scotland:

The Nigg cross slab and Rosemarkie’s collection of carved stones are widely recognised as among the finest in the Pictish corpus, and the Applecross fragments rival them in their supreme, virtuoso quality. This is the first concrete evidence for a single Pictish artistic hand on multiple artworks – a master carver or expert team whose oeuvre spanned both Easter and Wester Ross and who created some of the greatest surviving art-historical monuments in Britain.

So, given the quality of its carving, and its proximity (as the crow flies) to Rosemarkie, could the Achareidh fragment be the work of that same master carver?

Three scenarios for its presence at Achareidh

Assuming it might be, I’ve been considering three scenarios for the source of the fragment:

It was part of a cross-slab at Rosemarkie, and came to Achareidh by unknown means

It came from another Pictish site, related to Rosemarkie but closer to Achareidh

It was part of a sculptured cross-slab originally located at Achareidh itself

I have no idea which (if any) of these is correct, but the undeniable fact is that the fragment ended up at Achareidh somehow. So which scenario is the most likely?

Did the fragment come from Rosemarkie?

If the fragment did originally come from Rosemarkie, a not-unlikely scenario is that it was carried off as a souvenir by an 18th or early 19th-century antiquarian. Indeed it’s possible to imagine that an earlier owner of Achareidh House brought this fragment home as a curio, and it was later lost about the grounds.

Helpfully, George Bain provides a full list of the owners of Achareidh House, from Capt. John Fraser in 1791 to Lt. Col. Montague Clarke, whose workmen found the fragment in 1890. And as we’ll see later, there are hints of an antiquarian tendency on the part of Montague’s father Augustus Clarke, who bought the house in 1839.

Was it found at a site closer to Achareidh?

But even if it was the output of the Rosemarkie sculpture workshop, does the fragment necessarily need to have come from Rosemarkie itself? What about scenario 2, that it came from a site closer to Achareidh? The Rosemarkie carver also worked at Nigg and Applecross, so why not other places?

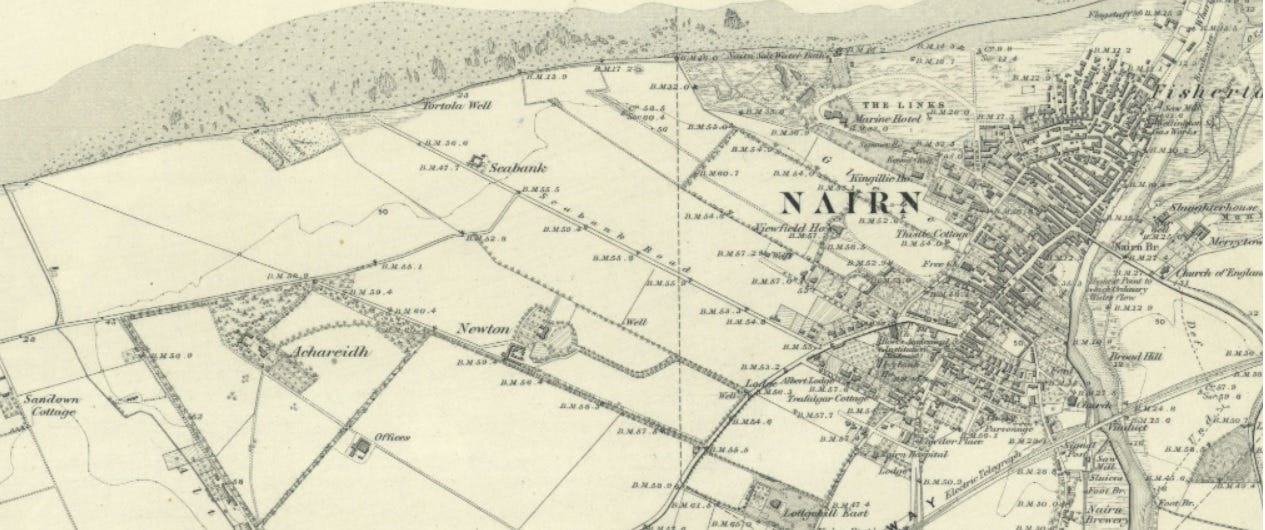

As it happens, there is a candidate site just a couple of miles west of Achareidh. For want of a more accurate toponym, it’s usually known as Wester Delnies, although it’s a good bit further west than the modern-day farmhouse of that name.

I’ve written about this site before: it’s the site of a very worn Pictish cross slab known as the Kebbuck Stone. It’s circled in red at the left of the map below (Achareidh, now part of Nairn, is also circled).

In my previous blog I looked at the historiography of the Kebbuck Stone and at the landscape features around it, and concluded that it must have been the site of a Pictish church, although not necessarily a large or important one.

Partly, that’s because there’s only one sculptured stone associated with the site. But if the Achareidh fragment came from Wester Delnies, it would mean there were multiple carved stones at the site, as the fragment isn’t part of the fully-intact Kebbuck Stone.

That in turn might indicate a larger, more important church. And there’s perhaps the tiniest hint that Wester Delnies may have been a more important site than it seems, in a place-name unearthed by Dr Alasdair Ross in 2003.

A possible place-name clue

In his PhD thesis on land organisation in medieval Moray, Ross identified a dabhach (medieval land unit) in the area of Wester Delnies that in 1649 included the farmsteads of Campbeltoun, Crafton, Bailieannick, Frasertoun and Smithtoun.

All of those are Scots names, apart from Bailieannick. The first part of that name is from Gaelic baile, a farmstead. But what about ‘annick’? There is a well-attested Gaelic place-name element annait (often appearing as annat or annet), which denotes an early Christian site.

Digging around for some background on annait place-names, I found this reference to a 1995 article by Professor Thomas Owen Clancy of Glasgow University:

The significance of annait as a name has been much discussed (Watson 1926, 250; MacDonald 1973), but a recent study has identified it as indicating a ‘mother church’, providing pastoral care for a secular estate, and therefore of some local significance (Clancy 1995, 114).

So… if this 17th-century place-name Bailieannick preserves a memory of a Pictish ‘mother church’ (the fore-runner of a parish church) in Wester Delnies, it could be possible that this church had multiple cross slabs, and hence that the Achareidh fragment could have come from there.

However, I emailed Professor Clancy about this, and he very kindly replied to say that Bailieannick “doesn’t seem promising” as an annait name. And indeed all the other annait place-names preserve the final ‘t’, so the ‘ck’ at the end of Bailiannick most likely rules out an annait root.

So we’re back to having no evidence of an important church with multiple sculptured slabs on the Wester Delnies site, somewhat ruling out scenario 2.

Was there a Pictish site at Achareidh itself?

What about scenario 3, then: that the Achareidh fragment is part of a Pictish monument that was situated on or near the spot where the fragment was found?

This seems to have been Bain’s view, as in 1893 he wrote:

A further search may yet reveal other portions of the ancient monument to which it belonged.

As far as I’m aware, if any further search has been conducted, it hasn’t turned up any more portions of the monument. But is there any other evidence that there might have been a site here? This is my cue to look for place-names and landscape features that might be suggestive of a church site.

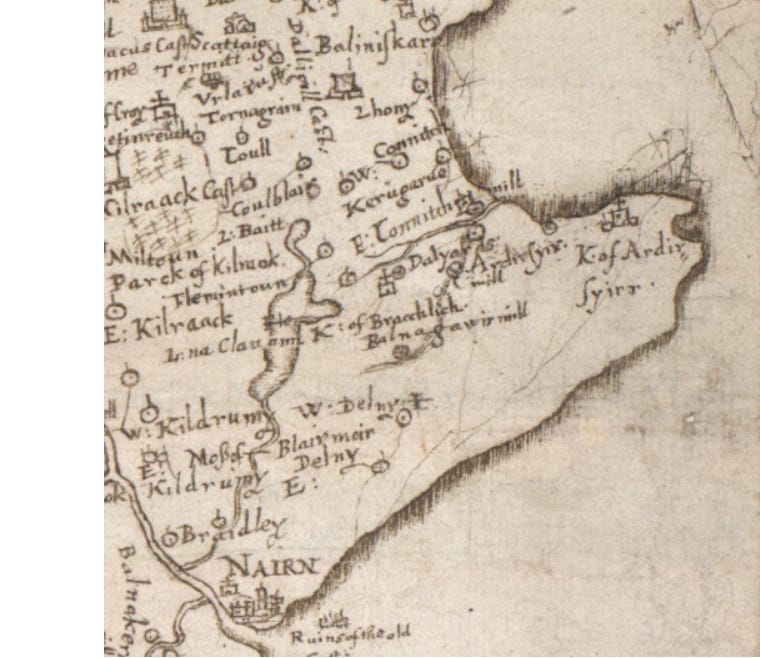

Unfortunately, both searches draw a blank for me. There are no suggestive place-names, either in the modern topography or on historical maps. Timothy Pont’s map of 1590, for example, shows the coastal area between Nairn and Ardersier as an unsettled stretch of low-lying carse (agricultural) land.

(NB I’ve turned the map below 90° clockwise to make Pont’s writing legible—so West is at the top.)

The same is true of General Roy’s map of the Highlands from around 1750 (below, which shows nothing on the site of Achareidh other than open rig-and-furrow fields.

Fast forward to 1871, and the first edition Ordnance Survey six-inch map (below) also contains nothing suggestive, although Achareidh House is now in existence, towards the left of the map below. But there’s no sign of any curving field boundaries or property boundaries, and no odd bends in any roads that might hint at the presence of an early church site.

Incidentally, the name Achareidh itself is no older than 1839, when Augustus Clarke—he of the possible antiquarian tendencies noted above—bought the house and changed its name from ‘Nairn Grove’. Bain notes that ‘Achareidh’ means ‘the cleared field’ in Gaelic.

I’m left concluding that the only piece of evidence to support the existence of a high-status Pictish church at Achareidh is the stone fragment itself. But the fact that this fragment was small and portable, and that no more fragments have been found in the area, strongly suggests that it didn’t originate on this site. On that basis, I’m tempted to rule out scenario 3 altogether.

So if it didn’t originate on the site, and it didn’t come from Wester Delnies, where did it come from? My first suspicion was Rosemarkie, on account of the quality of the carving, and knowing that Rosemarkie was the base of a master carver whose key-pattern abilities were second to none.

The lost fragment

In fact I did have a fond series of thoughts that I might be able to visit Achareidh House to see the fragment, and maybe photograph it, and maybe ask Cynthia Thickpenny for her opinion on it.

In this quest I enlisted the very generous help of my uncle, who lives in Nairn and was until recently a trustee of Nairn Museum. But sadly, his enquiries came to nothing: it appears the fragment is no longer in the house and the present owner knows nothing of it or its possible whereabouts.

In other words, the Achareidh Fragment is now the Lost Achareidh Fragment, and the photo at the top of this blog, taken by W.C. Gordon of Nairn in or before 1903, is the only remaining record of what it looked like.

So while the quality of the key pattern carving may suggest Rosemarkie, with my non-expert eye I can’t tell if it is actually the work of the Rosemarkie “master carver”. If it isn’t, the field opens wider, as sculpture fragments with high-quality key-pattern carving have also been found in quantity at Burghead (see below) and Kinneddar.

That leads me to one final thought, and I’m going to point a tentative finger, Cluedo-style, at Augustus Clarke, who owned Achareidh House from 1839 until his death in 1886.

Clarke was a man “of scientific tastes”, according to Bain, who “for a series of years kept meteorological observations of considerable importance.” As a well-to-do man of science, Clarke would have been connected with men of a similar social class and interests in Moray and Nairn.

On that basis, it’s not unlikely that he was a member of the Elgin and Morayshire Literary and Scientific Society, set up in 1837 by and for local antiquarians. This society was fascinated with the Pictish fort at Burghead, and in 1860 it organised an excavation of the site.

(NB for the above info I’m indebted to Christine Clerk’s excellent 2019 MSc dissertation on the history of archaeological thought surrounding Burghead.)

Archaeological digs in those days weren’t conducted with anything like the rigour that modern archaeologists apply to their work. So is it possible that Augustus Clarke joined in this dig, took a souvenir home with him (not unusual for the time), and subsequently lost it about his property—only for it to turn up again 30 years later when it was found by his son’s workmen?

In reality, I suspect we’ll never know how the fragment came to be at Achareidh House (unless any readers have more info to impart!) But given all the evidence I’ve considered in this blog, I’d say that on balance it’s more likely to have been a stray collector’s curio than a trace of a lost Pictish ecclesiastical site on the southern shore of the Moray Firth.

References

Allen, J. Romilly and Anderson, Joseph. The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland vol. 2, 1903.

Bain, George. History of Nairnshire. Nairn, 1893.

Carver, Martin. Post-Pictish Problems: The Moray Firthlands in the 9th-11th Centuries. Rosemarkie: Groam House Museum, 2008.

Clancy, Thomas O. “Annat in Scotland and the origins of the parish.” Innes Review, 1995.

Clerk, Christine. Burghead: A history of archaeological thought. MSc dissertation, University of Aberdeen, 2019.

Driscoll, Stephen T., Geddes, Jane and Hall, Mark A. (eds). Pictish Progress: New Studies on Northern Britain in the Early Middle Ages. The Northern World, vol. 50. Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden, Netherlands, 2010.

Márkus, Gilbert. “Can Iona Shed Light on Rosemarkie?” (online lecture, Groam House Museum, Rosemarkie, October 20 2022).

Ross, Alasdair. The Province of Moray, c. 1000-1230. PhD thesis, University of Aberdeen, 2003.

Thickpenny, Cynthia Rose. “Abstract pattern on stone fragments from Applecross: the master carver of Northern Pictland?” Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 148 (2018): 147–176.

The only other mention I could find was from 2008, when Achareidh was suggested by Professor Martin Carver in his Groam House Museum lecture (see References) as a possible site for a “sister monastery” to Rosemarkie, on the basis of the existence of this fragment there.

These small memorial stones are usually found in a group at a major church site with a graveyard, and Kinnedar is the only site where they occur above the Mounth. I’ve double checked that there’s no trace of them at Rosemarkie or Burghead. So there is no doubt it comes from the Kinnedar workshop as part of a group of personal memorial stones.

It is very rare to find one of these small memorial stones in isolation, but when they are, they are usually carved both sides (this fragment isn’t) and they have more complex iconography accompanying them. So I think the chances are slim that it was originally placed on a grave at Achareidh, especially as there is so far no evidence of a big church with graveyard there. But, odd things can happen, and I wonder if it was a unique case of a stray gravestone at Achareidh, bearing in mind that it was found when digging a hole, not just a surface find, and that they made a point of saying it was on the highest point of the land, which is definitely suspicious of a cairn/grave. So, curio or grave, I can’t say for sure which. But certainly originating from Kinneddar in the mid-700s.

The Achareigh fragment appears to originate from Kinneddar, and there’s a few reasons why. The main reason is that there is a group of small personal memorial stones (about 1m high) which come from there, and surprisingly four of them, Drainie 9 11 15 and 32, all have exactly this same key pattern on their arms, although their centres are each different. I say surprisingly, because, it’s almost like Kinneddar is discovering mass production, and I’ve not seen that anywhere else in Pictland. It’s a pity we don’t have the Achareidh fragment, because I wouldn’t be surprised if it was a piece off one of these other Kinneddar stones, especially Drainie 15. Otherwise it is part of a fifth example from Kinneddar, all with the same key, which is pretty impressive!

And, this is very helpful, because in my research I dated these to the mid 700s, and Dr Jane Geddes in her research says the St Andrews group must start c 740 and go for a few decades.