The pierced Anglo-Saxon coins of Moray: A clue to early lordship?

In which I investigate whether a series of ninth-century coin finds can tell us anything about the distribution of power centres in early medieval Moray

(NOTE: With thanks to Adrián Maldonado for making the time to talk to me about the Elgin coin, and for sending me some much-appreciated background material.)

[UPDATE 19th March: Thanks to all of the scholars who have commented on this post, either here, on Facebook or via email, with some really interesting insights. I have made a few corrections and added some footnotes.]

This blog is about an idea that’s been on my mind since I watched a talk by Dr Adrián Maldonado to the North of Scotland Archaeological Society in October last year.

Adrián is the Galloway Hoard Researcher at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, focusing not just on the Galloway Hoard but on ‘Viking-age silver and hoarding practices’ generally. (A dream job!)

One of the Viking-age hoards that he’s researching is the Croy Hoard, found by two different people on the Mains of Croy farm in Inverness-shire in 1875 or 1876.

As metalwork hoards go, it’s nowhere near as spectacular as the Galloway Hoard. But a couple of the items in it are extremely interesting, and I had an idea they might tell us something about power dynamics in the Moray Firth area in the late ninth century.

The pierced ninth-century coins of Moray

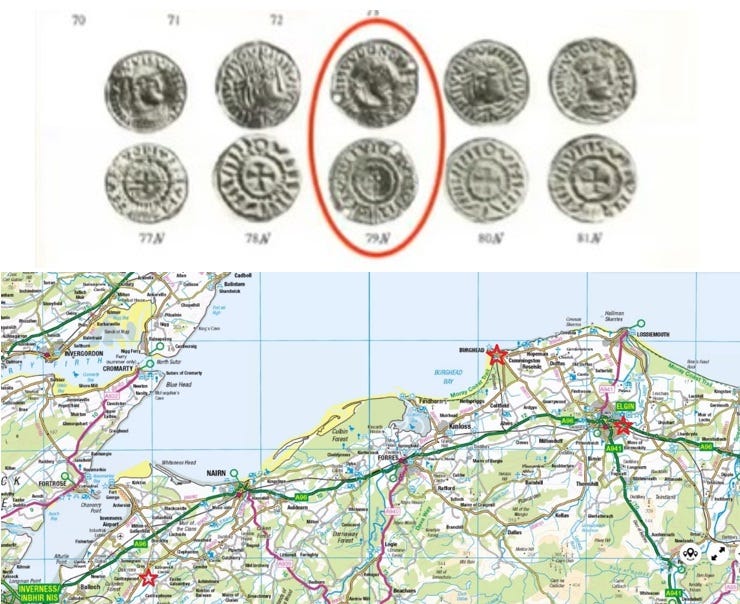

The items in question are two silver Anglo-Saxon pennies—one of Æthelwulf of Wessex (father of Alfred the Great) dated to c. 843 to c. 848, and one of Coenwulf of Mercia, dated to 796 to c. 805.

The presence of these coins, along with a silver mesh ribbon in the Anglo-Saxon Trewhiddle style,1 has allowed the whole hoard to be dated to the second half of the ninth century.

What’s interesting about these coins—and this is what Adrián focused on in his talk—is that they’re both pierced twice, top and bottom. This probably means that the person who owned them didn’t use them as currency or bullion, but instead wore them like jewellery, as a display of status.

And these aren’t the only pierced ninth-century coins to be found along the southern Moray Firth littoral. Excavations at Burghead, the enormous Pictish-era promontory fort 27 miles east of Croy in Moray, have so far turned up four Anglo-Saxon coins, two of them pierced in the same way.

The pierced coins from Burghead are both of Alfred the Great (r. 871–899). In 2023, the Northern Picts Project also found two Northumbrian coins; one of Bishop Wigmund of York (fl. 837–854), and one of Æthelred II (r. 801–804).

Unlike the Alfred coins, these Northumbrian coins are not pierced for wearing. (Perhaps they didn’t have the same kind of cachet.)

Even more interestingly, Adrián noticed that another late ninth-century coin find from Moray, now in the British Museum, is also pierced top and bottom.

This one isn’t an Anglo-Saxon coin but an imitation gold solidus of Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne and emperor of the Franks from 813–840. It was an antiquarian find and its exact findspot isn’t known, except that it was somewhere near Elgin.

My idea was that the distribution of these pierced coins might tell us something about power and rank in late ninth-century Moray. What follows is extremely hypothetical, so please take it in the spirit of ‘thought experiment’ rather than ‘actual theory’.

More high-status Anglo-Saxon material from Burghead

It’s fair to say that the bulk of the high-status Anglo-Saxon material in Moray has been found at Burghead.2 As well as the four coins outlined above, there is a famous piece of silver, in the same ‘Trewhiddle’ style as the silver mesh ribbon from Croy.3

This item was found in 1826 and was long considered to be the rim of a (Viking) drinking horn. However, in 1973, Professor James Graham-Campbell examined it closely and concluded that it is actually could equally be the mount from a mid- to late ninth-century Anglo-Saxon blast-horn.4

Drawing on riddles from the late Anglo-Saxon Exeter Book, as well as manuscript illustrations from the Harley Psalter, Graham-Campbell demonstrated that such horns were used both in hunting and in battle. He concluded that the instrument from which the mount came was:

[P]art of a noble warrior’s war-gear… a fine piece of equipment belonging to a 9th-century Anglo-Saxon warrior.

He could not say how this high-status item from England had come to be in Burghead, but his suggestion was that:

The possibility of Viking intervention must be borne in mind.

Viking intervention or not, if we take the horn-mount and coins together, it suggests that someone who occupied Burghead in the late ninth century had somehow acquired a collection of fine English metalwork, of which the coins of Alfred were perhaps particularly prized.

If we expand our focus to the Croy and Elgin finds, we might conclude that people living in those places in the late ninth century had also acquired a certain amount of fine foreign metalwork.

Did they all form part of a diplomatic gift?

The idea I’m mulling is that all these items arrived in Moray together, sometime in the late ninth century, as part of a diplomatic gift.

The distribution suggests that the primary main recipient of this gift was based at Burghead, since most of the material has been found there. My idea is that this person then distributed portions of it to his associates in the Moray region.

For this we have to bear in mind that the giving of high-status gifts was at the core of aristocratic social relations in early medieval Britain. A 2017 blog by Dr Matthew Firth of Flinders University gives some good insights into how it worked.

Dr Firth looks at the practice of gift-giving by Anglo-Saxon kings through the prism of early and high-medieval literature. First he cites Beowulf, an Old English poem that uses the famous phrase ‘þæt wæs gód cyning’ (‘that was a good king’) to describe Scyld Scéfing, who was:

[A] man known for violence against his enemies, and his gifts of treasure to his friends.

He then moves on to the Icelandic sagas, showing how a tradition of gift-giving by English kings has been preserved in these later stories.

Notably, he cites Egil’s Saga, which places the hero at the battle of Brunanburh in 937, fighting on the side of the English king Æthelstan (r. 924–939). Egil expects to receive a reward for this service, which he eventually receives. Firth notes:

Æthelstan must both reward Egil for his part in the battle and compensate him for the loss of his brother during the fighting. Thus he presents the Icelander not just with one of his own arm-rings, but then two chests of silver, and finally two more gold arm rings.

Firth observes that the memory of this tradition is surely accurate, as the tenth-century poem about the battle of Brunanburh preserved in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle confirms Æthelstan as:

Lord of earls [and] ring-giver of warriors

It seems to me that the coins and silverware found in Moray wouldn’t be out of place in a gift from a high-ranking Anglo-Saxon nobleman, or even a king.

Moravian connections to Anglo-Saxon kings?

I’ve often thought about the Burghead horn mount in those terms, especially when contemplating the relationship between Æthelstan and Constantine II of Scots (r. 900–942).

As a subregulus (under-king) of the English king, Constantine attended Æthelstan’s court in England several times. He would surely have received gifts in return for his loyalty—until he snapped and led an army against Æthelstan at Brunanburh in 937.

The silver-edged blast-horn horn mount from Burghead is probably a bit too early, and perhaps in the wrong place, to have actually been a gift from Æthelstan to Constantine. But it is exactly the sort of gift that would have been given in that kind of context.

However, I’d never thought about the pierced coins in the Croy hoard as possible royal gifts, until Adrián made this suggestion in his NOSAS talk:

What are these coins of Alfred doing travelling up north and being displayed in this distinctive way? We don’t know, but… there’s a lot of interplay between Burghead, in the time that we don’t have any records of the kings of Picts… and the time of Alfred the Great, struggling against the Vikings.

He then floats the idea that:

It’s possible that there was an undocumented attempt to reach out and ally with strong kings of the north.

The suggestion (I think!) is that a Burghead-based king of Picts may have been entreated to fight alongside Alfred in his battles against the Great Heathen Army in the 870s.

It must be said straightaway that there is absolutely no hint of any such alliance in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle or any other source. But if it did happen, and the Burghead-based king accepted the terms, then, like Egil in Egil’s Saga, he would have been richly rewarded for his service.

And this is where the findspots of the other pierced coins become interesting.

Looking for power centres in ninth-century Moray

Separately (until now) from all this, I’d been thinking about whether it’s possible to discern how society was organised in Moray in the ninth and tenth centuries.

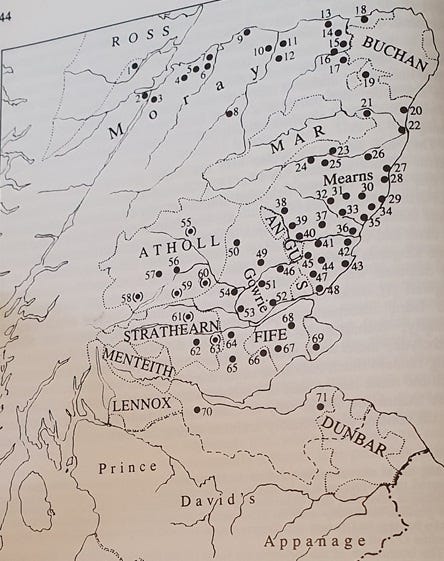

Written records for Moray only really begin in the twelfth century, so the ninth century is a blank. But it seems that in the early twelfth century, there existed in the heartlands of coastal Moray a pattern of landholding whereby the core, around Forres, Elgin and Burghead, was held by the mormaer (ruler) of the region.

This core was buttressed to the east and west by a series of smaller territorial units. In the twelfth century these were held by lesser lords known as toisíg (sg. toisech) in Gaelic, or ‘thanes’ in English.

These smaller territories were called thanages, and they existed at Cawdor (4), Moyness (5), Brodie (6) and Dyke (7) in the west of Moray, and at ‘Kilmalemnock’ (9) and ‘Rathenach’ (10) in the east. See the map below for the numbering.

There’s huge debate about the possible existence of thanes and thanages in Moray before the twelfth century. It’s dense stuff and I haven’t nearly got to the bottom of it yet. But Alexander Grant has argued that the title of toisech, or thane, was introduced to Scotland in the late tenth century. So it would be anachronistic to talk about thanes in Moray in the ninth century.

But in the absence of a more accurate title for the ninth century, I’m going to use ‘thane’ to mean the head man of a small territory, loyal to the king and responsible for raising a portion of an army when required to.

The pierced coins as clues to local power centres?

My idea was that the distribution of the pierced coins might hint at where these putative ninth-century ‘thanes’ were based, and whether they were based in places that we know were thanages later in the Middle Ages.

The Croy hoard – a connection with Cawdor?

Croy is by far the easier one. It’s just across the River Nairn from Cawdor, a thanage on record from 1295. The name Cawdor first appears in charters as Abbircaledouer, a Pictish/Brittonic name meaning something like ‘confluence of the hard water’. It has an Iron Age hillfort at Dún Evan, and an early medieval handbell that dates to sometime between 700 and 900 AD.

So as well as being a later thanage, Cawdor was surely an important place going back to pre-Gaelic, pre-Christian times. If I was looking for a ninth-century power centre where the items in the Croy Hoard might have belonged before they were buried, Cawdor would be my first choice.

What about the Elgin coin?

Elgin is much more difficult. We don’t know where exactly the coin was found, although it wasn’t in Elgin itself. The nearest thanage was ‘Rathenach,’ which seems to have lain between Elgin and the Spey, a distance of maybe six miles. But without more information about where the coin was found, or where Rathenach was, that’s as close as I can get.

So whether this coin formed part of a diplomatic gift that was distributed from a king in Burghead to a ‘thane’ based at ‘Rathenach’, it’s impossible to say. (I also imagine that a coin of Louis the Pious, a Carolingian emperor and son of Charlemagne, would be very highly prized (even if a forgery), and perhaps not one to give away.)

A final thought about a Pictish cross slab from Dyke

And that’s just about as far as I can get with this idea, except for one final thought. Another place in Moray that was a thanage in the twelfth century is Dyke, just west of the River Findhorn. In 1781, workmen digging the foundations for the new Dyke parish church unearthed a fine Class II Pictish symbol-bearing cross slab. That slab now stands in the driveway of nearby Brodie Castle and is known as Rodney’s Stone.

I’ve written about Rodney’s Stone before, in 2022. A couple of things I wrote then make me wonder if it, too, might be linked to a kingly gift like the one I’ve been hypothesising about.

Firstly, the art historian R.B.K. Stevenson dated the stone to around 850 AD, which, if accurate (and I know some would date this stone much earlier, and one archaeologist proposes the late tenth or early eleventh century), puts it into roughly the same period as the Burghead, Croy and Elgin finds.

Secondly, there are the observations made by Professor Katherine Forsyth when she analysed the stone—and its ogham inscription EDDARRNONN, which she interpreted as the saint’s name Ethernan—for her 1996 PhD thesis.

Looking at the two fish-beasts on the symbol-bearing face of the stone, she wrote:

Between the pair of opposed monsters there is an assortment of curvilinear motifs […]. In the centre is a large spiral disc decorated with pellets, above is an object that looks a little like a penannular brooch with expanded terminals, to the right is a crescent with pellets and to the left a circular disk decorated with a triskele, at the bottom between the monsters’ tails is another small disk decorated with a triskele.

She continued:

Each item is distinct and individual suggesting that they are intended to represent specific items, rather than merely fill the space with abstract ornament […]. If the upper item is indeed a brooch, then the crescent may also be a piece of metalwork, like the crescent-shaped silver plaque from Laws, Monifieth FOR. If the other items also represent metalwork then perhaps we have here two monsters guarding a hoard of treasure.

In my earlier blog, I noted the strong similarity between the treasure items depicted on the stone and the real items in the Croy Hoard. At the time, I saw both the stone and the hoard as evidence of anxiety about precious material possessions that might be looted at any moment by Norse raiders.

Does Rodney’s Stone depict a real treasure?

But now I’m wondering if there’s a more direct connection. Could the treasure on the stone actually depict a real treasure, owned by the patron of the stone? And if so, could it depict the patron’s share of a gift of which the Croy, Burghead and (perhaps) Elgin coins were also a part?

This might seem a conspiracy theory too far. But at the same time, any Christian warrior returning home safely from battle would want to give thanks to God—and the local saint—for his safe return.

I can easily imagine this local ‘thane’ returning from fighting the Great Army, and commissioning a fine cross slab for his church with a dedication to St Ethernan, but not being able to resist including a nod to the reward he’d received for his service.

In which case, the stone’s ‘large spiral disk decorated with pellets’ and ‘circular disk decorated with a triskele’ might be glimpses of real ninth-century Anglo-Saxon coins. A far-fetched thought perhaps, but one I find quite satisfying.

UPDATE 12/04/24: For example, here is an Anglo-Saxon sceat of 710-760 AD from Spink’s website, which, like the Brodie carving, has pellets round the outer edge. Maybe there’s something of the “sinuous quadruped” from the l-h face of the coin in the curvilinear interior detail of the stone’s carved disc too. Or am I just seeing things?

Conclusion

To sum up, then, I started this blog wondering if the pierced coins found in three different places along the Moray Firth coast might offer clues to the locations of power centres in the late ninth century.

My hypothesis was that the coins had originally formed part of a diplomatic gift to a Pictish king in Burghead, perhaps as an incentive or reward from Alfred for providing military support against the Great Heathen Army. Parts of this gift were distributed to local ‘thanes’, and these ‘thanes’ were based in places that were (still) thanages in the twelfth century.

As a hypothesis it works fairly well for the coins in the Croy Hoard. The hoard was found not far from Cawdor, a later thanage and with plenty of evidence of having been an important place in the ninth century (and earlier) too.

But it doesn’t really work for the fake Louis the Pious coin found near Elgin. This coin seems to have a Frisian rather than English provenance,5 and we don’t know exactly where it was found, nor where the thanage of ‘Rathenach’ near Elgin actually was.

And as to whether the ‘treasure’ depicted on Rodney’s Stone at Brodie represents the ‘thane’ of Dyke’s portion of the same diplomatic gift—it’s an entertaining thought, but it relies on far too many speculative assumptions to hold any weight at all.6

So after all that. I’m not sure there’s too much I can take from this exercise (apart perhaps for a bit more circumstantial evidence for a power centre at Cawdor) unless and until more Anglo-Saxon material comes to light in Moray. But it’s been very useful to think it through—and thank you as ever for coming along on my investigation!

References

Blackburn, Mark. ‘Gold in England during the “Age of Silver” (eighth–eleventh centuries).’ In Silver Economy in the Viking Age, edited by James Graham-Campbell and Gareth Williams, 55–98. Italy: Left Coast Press, 2007.

Firth, Matthew. Kingship in the Viking Age: Icelandic Sagas, English Kingship, and Warrior Poets. The Postgrad Chronicles blog, August 2017.

Forsyth, Katherine. ‘The Ogham Inscriptions of Scotland: An Edited Corpus.’ Unpublished PhD thesis, Harvard University, 1996.

Graham-Campbell, James. ‘The 9th-century Anglo-Saxon horn mount from Burghead, Morayshire, Scotland.’ Medieval Archaeology 17 (1973), 43–51.

Grant, Alexander. ‘Thanes and thanages from the eleventh to the fourteenth centuries.’ In Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community, edited by Alexander Grant and Keith J. Stringer. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993.

Innes, Cosmo (ed.) Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis. Edinburgh, 1837

Maldonado, Adrián. The Croy Hoard. Online talk to the North of Scotland Archaeological Society, July 2020.

Maldonado, Adrián. Crucible of Nations: Scotland from Viking Age to Medieval Kingdom. Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland, 2021.

Maldonado, Adrián. Beyond Picts and Vikings: Northern mainland Scotland 800-1100. Online talk to the North of Scotland Archaeological Society, October 2023.

Ravilious, Kate. ‘Land of the Picts’. Archaeology. September-October 2021.

Trench-Jellicoe, Ross. ‘A richly decorated cross-slab from Kilduncan House, Fife: description and analysis.’ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 135 (2006), 505–559.

Many thanks to Dr Victoria Whitworth and Professor James Graham-Campbell for putting me right on this: this silver mesh ribbon is not “in the Trewhiddle style” but it is similar to an item found in the Trewhiddle Hoard. It is also not necessarily ‘Anglo-Saxon’ in origin but could be from anywhere in Britain or Ireland.

Although it should be said that Burghead has been extensively and repeatedly excavated, while the other coins have been chance finds, so this supposition may well be inaccurate.

See note 1 above.

Thanks to James Graham-Campbell for the clarification on this - it is not definite that it is the mount of a blast-horn; it could still be from a drinking horn, but doesn’t have to be.

Many thanks to Professor Rory Naismith who has commented (on Facebook) that this coin could in fact have come to Moray from England, even if manufactured in Frisia. However, he “doubt[s] very much that this cluster of coins came up in one go” but rather that they are evidence of “longer and more punctuated relations”.

That said, Professor Jane Geddes has drawn my attention to the knife and scabbard depicted on the St Andrews Sarcophagus, the detailing of which suggests they represent a real Anglo-Saxon or Frankish item (perhaps owned by the patron of the sarcophagus).

Could it also be possible that the coins were plunder of some sort and worn as a status symbol?

I absolutely love reading posts like this that explore possibilities rooted in what available evidence we have--and the connection between the stone and treasure/gift giving/hoards is a great line to think through.