Was Sueno’s Stone originally one of a pair?

In which I investigate the curious case of the ‘curious carved pillars’ shown on early maps of Moray

Of the many intriguing theories about Sueno’s Stone—a 6.5m tall, ninth or tenth-century cross slab that stands near Forres in Moray—one of the most suggestive is that it was originally one of a pair.

As a theory, it’s only around 30 years old, stemming from the publication in 1996 of a report detailing an archaeological dig around the stone. But its genesis goes back to the late 16th century and the production of the earliest detailed map of Moray.

In this blog I’ll examine the evidence for and against the existence of a pair of pillars on the Sueno’s Stone site, and come to a (to my mind) fairly convincing conclusion.

Timothy Pont, the map-maker who surveyed Scotland

Between 1580 and 1600, Timothy Pont, son of Robert Pont, a prominent figure in Scotland’s Reformation, carried out the first large-scale initiative to map the whole of Scotland. The effort he put into this project is clear from the 78 richly detailed drafts that survive in their original form, drawn and annotated in Pont’s own hand.

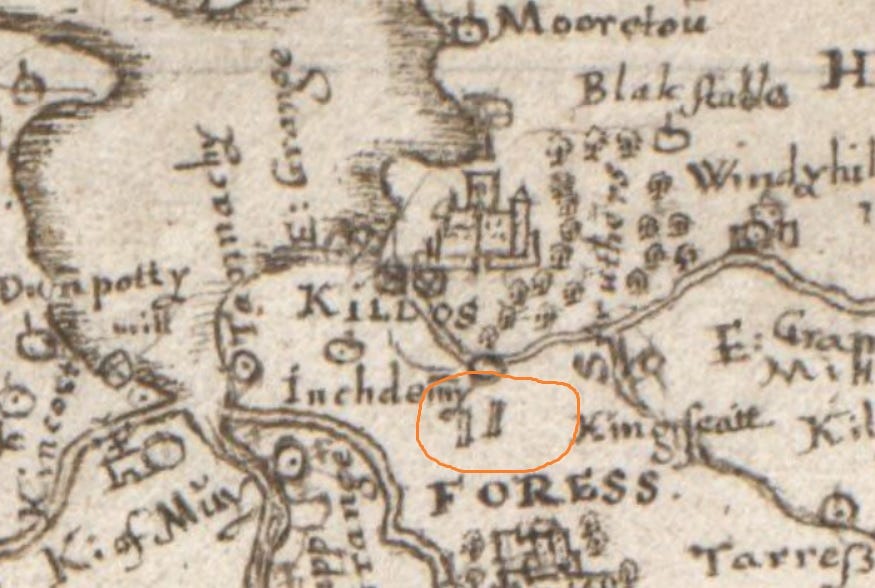

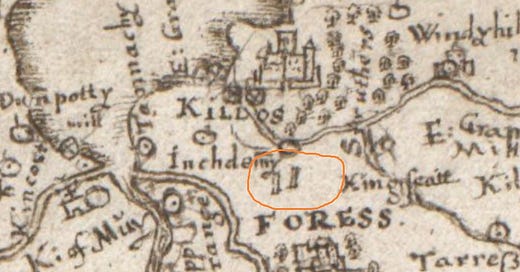

One of these is his ‘Mapp of Murray’, also known as Pont 8. It offers fascinating insights into the castles, forests, place-names, industries, routeways and lost lochs of late 16th century Moray.

Although not very much is known about Pont’s life, scholars agree that he personally visited the places he surveyed. In many cases he drew the actual likenesses of the castles, abbeys and grand houses he encountered, rather than using symbols or generic images to denote them.

And it’s this that’s given rise to the idea that Sueno’s Stone originally had a twin. On the spot where the stone stands—and seems to have stood since it was first raised—Pont drew not one stone, but two: rectangular pillars, of equal height, standing on the sandy ridge between Forres and Kinloss.

A cartographical mistake?

Intriguing as they are, Pont’s depiction of twin pillars on the Sueno’s Stone site didn’t come to mainstream attention until 1996, when the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland published the findings of an archaeological dig conducted at the stone in 1990-1991.

Written by the dig’s lead archaeologist Rod McCullagh, the report included a review of the literature previously produced about the stone, including Pont’s map.

McCullagh wrote:

Only one document of any authority records the location of the stone prior to the 17th century. On the manuscript of Timothy Pont’s Mapp of Murray (c.1590) two stones have been depicted lying north of Forres.

McCullagh’s first thought was that Pont hadn’t actually seen the stone himself, but had rather read or been given a description of its two very different faces.

It might be suggested that these marks merely reflect a confusion by the illustrator, mistaking a survey account of either side of the stone for two separate monuments.

He contacted a leading Pont scholar, Dr Jeffrey Stone, to ask if this could be a plausible explanation. But rather than clearing the matter up, Stone’s reply seems only to have thickened the plot:

This view is not consistent with the general quality of this particular manuscript, in which the features have been carefully inserted and it would be surprising had the second stone been merely an error of the cartographer (J Stone, pers comm).

What’s more, it turned out Pont wasn’t the only map-maker to record two stones on the site. McCullagh noted that three other 17th and 18th century maps also feature the mysterious twin:

When the map was engraved by Blaeu for printing, from a draft prepared by Robert Gordon (c. 1640), the two stones were again represented and again must have been deliberate insertions. The same features appear on Roy’s map of Moray (1750) and on Ainslie’s 1800 edition of his government-commissioned series. On Ainslie’s map, the location of Sueno’s Stone is inscribed ‘two curiously carved pillars’.

He concluded that the possibility of two stones must be given serious consideration:

Ainslie is regarded as the foremost cartographer of his generation and both his and his predecessor Pont’s hitherto unnoticed references to the monument’s missing twin must arouse considerable curiosity.

A gateway to a royal domain?

The thought of a pair of pillars on the site is quite extraordinary, because even on its own Sueno’s Stone is an exceptional monument. Over twice as tall as the next tallest early medieval stone in the area, it towers over human observers.

In 1981, Leslie Southwick wrote in a booklet published by Moray District Libraries:

Today, close to the road to Kinloss and Burghead, with houses and trees nearby, and the sea to the north, the monumental proportions of Sueno’s Stone still have the power to impress the visitor. Two centuries ago, set against a bleak and threatening landscape, the stone must have seemed positively daunting.

Even now, encased in glass and hemmed in by the Forres bypass and encroaching housing developments, its size is still awe-inspiring. How much more daunting would it have been if it had been not a single stone, but a pair of pillars: not so much a monument as a portal?

I’m powerfully reminded of Tolkien’s Argonath, the twin Pillars of the Kings that guard the river entrance to Gondor:

As Frodo was borne towards them the great pillars rose like towers to meet him. Giants they seemed to him, vast grey figures silent but threatening. Then he saw that they were indeed shaped and fashioned: the craft and power of old had wrought upon them, and still they preserved through the suns and rains of forgotten years the mighty likenesses in which they had been hewn.

- J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

I must admit I find the idea of Sueno’s Stone as one half of a Moravian Argonath very seductive. For one strand of my MA research I’m looking at whether the stone might have formed part of a wider royal landscape in this part of Moray, taking in the huge promontory fort at Burghead and the impressive ecclesiastical site at Kinneddar. A pair of pillars would form a satisfyingly monumental entrance into this royal domain.

Is it really likely, though?

It's a seductive idea, but is it a plausible one? In reality, quite a few things suggest not. Firstly, no textual records mention two stones on the site. That’s not necessarily a deal-breaker, as there’s a gap between Pont’s map appearing and the first written record of the stone, during which the second stone might have disappeared.

But how big a gap—and is it long enough for a second stone to have vanished without trace or comment?

Both Southwick and McCullagh cite Alexander Gordon’s Itinerarium Septentrionale of 1726 as the first historical mention of Sueno’s Stone. On page 158 of his tour of Scottish antiquities, Gordon wrote:

The stone, near the town of Forress […], in Murray, far surpasses all the others in Magnificence and Grandeur, and is perhaps one of the most stately Monuments of that Kind, in Europe. […] It is all one single and entire Stone; Great Variety of Figures, in low Relievo, are carved thereon, […] but the Injury of the Weather has obscur’d those towards the upper Part.

Since Pont’s map showed a pair of pillars in 1590, that leaves a fairly acceptable 136-year gap during which the second pillar might have been lost.

But both Southwick and McCullagh seem to have overlooked an earlier mention of the stone. In the 1640s, another map-maker, Robert Gordon, was commissioned to redraw some of Pont’s maps for publication in an atlas being prepared by Joan Blaeu in Amsterdam. As well as redrawing Pont 8, Gordon provided a written description of Moray, entitled Nova Moraviae Descriptio. In it, he noted:

At a junction on the road to Forres stands a large column, consisting of one stone, a monument to a battle fought by our King Malcolm son of Kenneth against the commanders of the Dane Sweyn’s forces; they are now mostly eaten away by age and the letters are not clear. [my emphasis]

Robert Gordon was a native of Aberdeenshire, and his Nova Moraviae Descriptio would surely have been written from first-hand observation. If he says there was only one stone on the site in c. 1640, that narrows the window of possibility for the disappearance of the second stone to just 50-odd years. That doesn’t seem long enough for a second pillar to have passed out of local memory and tradition.

Were pairs of stones common in the first millennium?

Then there’s the fact that pairs of sculptured stones—especially crosses and cross-slabs—just don’t seem to have been a ‘thing’ in the first millennium AD.

I’m very willing to be corrected on this, but in all my research to date, I’ve never come across a genuine pair of freestanding pillars from the early medieval period. I’ve certainly come across stones that are thought of as ‘pairs’. The Ruthwell Cross and Bewcastle monument, for example, are often considered together due to their stylistic similarities, but physically they stood 30 or so miles apart.

The Dupplin Cross and Invermay Cross are also often mentioned together, because they seem to have marked the northern and southern boundaries of the royal Pictish domain at Forteviot. But again, their actual physical locations were miles apart. And while the two 9th century crosses at Sandbach do stand together, they’re thought to have been moved to their current location in the 16th century.

In fact the only genuine ‘pair’ of early medieval carved stones I can think of are the two Class I Pictish symbol stones at Congash, near Grantown-on-Spey. These two small incised stones stand either side of the entranceway into what’s usually described as a small chapel site, although they have no Christian iconography and may be pre-Christian—or at least non-Christian—in origin.

Does a second pillar make iconographic sense?

And that’s the other thing that gives me pause about Sueno’s Stone being one of a pair. Its west face bears a huge Christian cross; an icon that symbolically stands alone.

A second cross of similar size would make little sense: there is only one Christ, and the Crucifixion is a single act, offering a unique promise of salvation. The cross is thus meant to command the viewer’s attention and provide a focus for contemplation.

But when two pillars are placed side by side, their function is generally to draw attention to the space between them. They become a frame for—or gateway to—whatever lies beyond, rather than monuments on their own terms.

I may be wrong about this, though. The leading historians of Pictish art, Isabel and George Henderson, were very prepared to consider Sueno’s Stone as one of a pair—and even to offer a reasonable explanation for twin pillars as a stylistic choice.

Referencing McCullagh’s excavation report in their 2004 book The Art of the Picts, they say:

Sueno’s Stone is on an unusually ambitious scale. In this respect it is as likely to be a conscious cultural gesture—especially in view of the good evidence there were originally two ‘curiously carved pillars’ on the site—by a 9th century patron fresh from a visit to Rome, who wanted the equivalents of the Columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius on his doorstep, as that we should regard the camp scenes, parades and massacres as an intelligible act of local reportage. [my emphasis]

Assessing the map evidence

The ‘good evidence’ that the Hendersons refer to is the evidence of the maps noted by McCullagh. Here’s his summary again:

When [Pont’s] map was engraved by Blaeu for printing, from a draft prepared by Robert Gordon (c. 1640), the two stones were again represented and again must have been deliberate insertions. The same features appear on Roy’s map of Moray (1750) and on Ainslie’s 1800 edition of his government-commissioned series. On Ainslie’s map, the location of Sueno’s Stone is inscribed ‘two curiously carved pillars’.

I’ve looked at all of these maps on the National Library of Scotland website, and I’m not sure the situation is quite as straightforward as McCullagh suggests.

For a start, while John Ainslie’s 1789 (not 1800) map does indeed show two obelisks on the site, with the label “curious carved pillars” (not “two curiously carved pillars”), an earlier map of Ainslie’s from 1785 shows only one.

I don’t know what might have prompted Ainslie to re-cast one pillar as two, especially as we know from Alexander Gordon’s 1726 account that there was only one stone on the site in the 18th century.

But it’s worth noting that Ainslie’s 1789 map displays a certain amount of “antiquarian enthusiasm” generally. Not only have Sueno’s Stone and its twin been transformed into Luxor-style obelisks, but both Forres and Burghead are labelled with spurious Classical names (‘Varis’ and ‘Ptoroton’) from De Situ Britanniae, a hoax manuscript that fooled many antiquarians before it was exposed in the 19th century.

Robert Gordon’s 1640 redrawing of Pont’s map does preserve the two stones, as McCullagh says. But as we saw above, in his written description of Moray that accompanied the map in Blaeu’s Atlas, Gordon stated that there was only one stone on the site.

General Roy’s 1750 map of Moray, by the way, shows nothing on the site that I can see.

Signs and symbols

So what’s going on here? Pont, Ainslie and Gordon were all serious about their work, and we can assume they visited Forres in the course of it. In their day, Sueno’s Stone stood very prominently beside the main road from Elgin to Forres, the primary west-east route through Moray, so they could hardly have failed to observe it. Yet sometimes they drew it as two pillars, sometimes as one.

All roads seem to lead back to Pont, as the earliest map-maker to draw two stones on the site. Pont is known for drawing many of his buildings from life, but that doesn’t mean he used the same approach with all of his map features. In an essay included in the 2001 book The Nation Survey’d: Timothy Pont’s Maps of Scotland, Dr Jeffrey Stone writes:

…Pont is inconsistent in his use of signs. For example, on manuscripts 6, 10 and 11 Pont wrote ‘mill’ against a sign that was not unique to mills […] whereas on manuscripts 8, 21 and 35 he used a sign specific to mills. On manuscript 23 he does both these things. Pont is disconcertingly inconsistent to today’s reader who may be tempted to assume more modern conventional practice. [my emphasis]

In other words, Pont used symbols (of his own devising) for many of his features, but did so inconsistently. Could the two stones on his map be a symbol, rather than a drawing from life?

In an essay in the same book, Christopher Fleet writes:

Many pre-Roman antiquities are both illustrated and described by Pont, such as the standing stone of ‘Dun Vorrich’ and ‘Dens brugh’ (Pont 2), the ‘great standing stones’ at Aquhorthies near Aberdeen (Pont 11), and the standing stone north of Livingston (Pont 36).

Aquhorthies in Aberdeenshire is a fine example of a Neolithic recumbent stone circle, which today comprises 14 stones of a presumed original 18. But on his map of the area, Pont depicts it in an identical manner to Sueno’s Stone: as two standing pillars.

If we’re looking for an answer to the question in this blog’s title, we may just have found it.

And… roll credits

When I write these blogs, I research them as I go. So when I started this one, I didn’t know I would end up finding that Pont’s twin pillars were a symbol he’d also used elsewhere. Now that I have, and weighing up all the other evidence too, it seems fairly certain that Sueno’s Stone was only ever one stone.

But.

In the style of a Marvel movie, this blog has a post-credits sequence. Because what I haven’t mentioned is that during the 1990-1991 excavation at Sueno’s Stone, something quite unexpected turned up.

Firstly, McCullagh and his team found a series of post-holes surrounding the east face of Sueno’s Stone in a rough semi-circle, which they believed could be related to the original raising of the stone. The report states:

Speculating from field evidence, it is not unreasonable to interpret these features as the remains of a scaffold or derrick used to raise the stone to the vertical.

More pertinently for this blog, the team found the same pattern of post-holes just to the south of the stone, leading McCullagh to conclude:

With […] caution, the second, eroded setting of features is seen as a duplicate of the arrangement of substantial post-holes set around the base of the monument […]. Taking inspiration from Pont’s map, it is speculated that two stones may once have existed.

So perhaps the question isn’t so settled after all!

References

Campbell, E., Driscoll, S. T. (2020). Royal Forteviot. In Council for British Archaeology Research Reports (p. 177). Archaeology Data Service.

Fleet, C. (2001). Pont’s Writing: Form and Content. In I.C. Cunningham (Ed.). The Nation Survey’d: Timothy Pont’s Maps of Scotland. East Linton: Tuckwell Press

Gordon, A. (1726). Itinerarium Septentrionale: Or, A Journey Thro' Most of the Counties of Scotland, and Those in the North of England. In Two Parts ... Illustrated with Sixty-six Copper Plates (p. 158). London

Henderson G. & Henderson I. (2004). The Art of the Picts: Sculpture and Metalwork in Early Medieval Scotland. London: Thames & Hudson, 135-136

McCullagh, R. (1996). Excavations at Sueno’s Stone, Forres, Moray. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 125, 697-718.

Lees, C., Orton, F. (2007). Fragments of History: Rethinking the Ruthwell and Bewcastle Monuments. United Kingdom: Manchester University Press.

Southwick, L. (1981). The So-Called Sueno’s Stone at Forres. Elgin: Moray District Libraries Publications

Stone, J. (2001) An Assessment of Pont’s Settlement Signs. In I.C. Cunningham (Ed.). The Nation Survey’d: Timothy Pont’s Maps of Scotland. East Linton: Tuckwell Press

A very interesting read Fiona. I enjoyed following you down this particular rabbit hole. You said there weren't any other paired Pictish stones. Had you considered the two Newton Stones as a possible pair of pillars? I haven't checked my notes but I'm pretty sure that Kelly Kilpatrick believes they were originally together.

Our excavation around Sueno’s stone was not an altogether comfortable experience. Constrained by the footprint of the foundations of the glass box and obliged to investigate this shape in a disjointed sequence of jig-saw shapes, our extraction of an even semi-sensible working interpretation proved painful. Our post-excavation analysis was designed to narrow the uncertainties but new ones emerged in the process. The interpretation sequence went from the field evidence - two adjacent, penannular post settings - to questions on contemporaneity (unanswered), shared function (case not proven but possibly) and then sought corroboration or insight from the documentary sources. The weaknesses of our data lie in our abilities and in the random sample of Sueno’s Stone’s surroundings that the modern footprint imposed. I do wonder whether, if we could look more broadly around other stones, as Gordon Noble has done at Rhynie, would we find more evidence for multiple settings or multiple stones. Many thanks for your very interesting, well-researched thoughts on the two Sueno’s Stones idea. To be honest, I pushed that idea out as I felt duty bound to stimulate interest and argument and to make the case for better excavation and better collaboration in future early medieval investigations. Rhynie makes my point!