Where are Scotland’s early medieval water mills?

In which I try to find any evidence at all for water-mills in northern Scotland prior to 1150

(My thanks to all those who have contributed thoughts and recommendations for this blog over the past few months: John R. Barrett, Thomas Owen Clancy, Murray Cook, Neil McGuigan, Gordon Noble, Simon Rodway, Cameron Wachowich and Alex Woolf.)

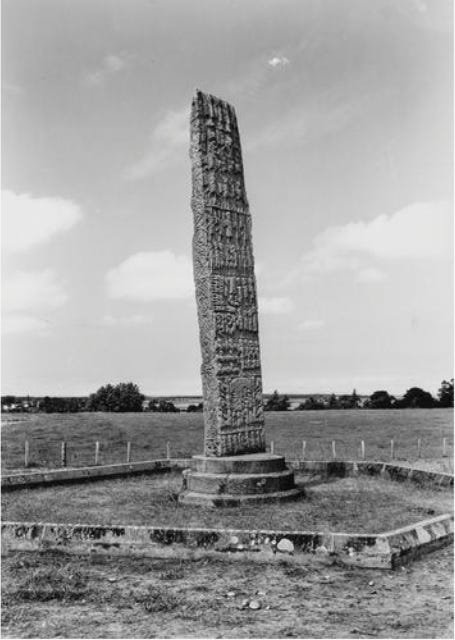

I’ve been down an odd and frustrating rabbit-hole recently. I’m due to give a lecture to the Pictish Arts Society next February on the landscape context of Sueno’s Stone, so I’ve been stepping up my efforts to establish what the landscape in this part of Moray might have been like in the ninth or tenth century, when the stone is generally thought to have been raised.

Part of my research involves combing the earliest surviving written records for the area for clues. This being early medieval Scotland, though, there are no written records for the ninth or tenth century—or for the eleventh century for that matter, or indeed most of the twelfth.

In fact, the first document that gives any kind of insight into this part of Moray dates from 1187. It’s a charter of Richard de Lincoln, bishop of Moray, confirming the lands that were granted to Kinloss Abbey by David I of Scotland on its foundation in 1150.

(The foundation charter itself doesn’t survive, and may not even have existed in written form—hence the need for the monks to get confirmation of their possessions in writing from the bishop.)

A ‘Scottish mill’ at Kinloss

And it’s in this charter that I make what I initially think is a pretty interesting discovery. One of the original parcels of land apparently granted to the abbey in 1150 was:

terram super quam Scottie molendinum stabat

which translates to:

the land on which the Scottish mill used to stand

I find this interesting for a couple of reasons. One is that this mill may be evidence for the existence of a community at or near Kinloss before the abbey was founded. A mill suggests other things too: the presence of carpenters and stonemasons—or indeed a specialist millwright—and the need to produce flour on a larger scale than could be done by hand-grinding corn with quern stones.

As there seem to have been no towns or villages in northern Scotland at this time, there’s a good chance that this community—if it existed—was a monastic one. That adds a bit more weight to the idea (which I discussed here) that there was an older ecclesiastical foundation on or near the abbey site before the Cistercians set up in Kinloss in 1150.

The second interesting thing is the designation of this mill as Scottie or Scottish. Before Scotland existed that word meant ‘Irish,’ and even in the twelfth century, a ‘Scottish mill’ meant an Irish-style mill.

[UPDATE 15th Oct: Thanks to Alex Woolf who has pointed out (on Facebook) that ‘Scottie’ doesn’t signify Irish here, but rather a native vernacular style—likely referring to its horizontal mill-wheel as discussed below.]

To confuse matters further, a an Irish-style ‘Scottish’ mill also came to be known as a ‘Norse mill,’ and there are lots of them in the Northern Isles—for example, at Dounby in Orkney. But they are much later in date and not relevant for this blog.

The horizontal Irish water-mill

What distinguishes a an Irish (or Scottish (or Norse) mill from other types of water-mill is that it was driven by a horizontal mill-wheel rather than a vertical one.

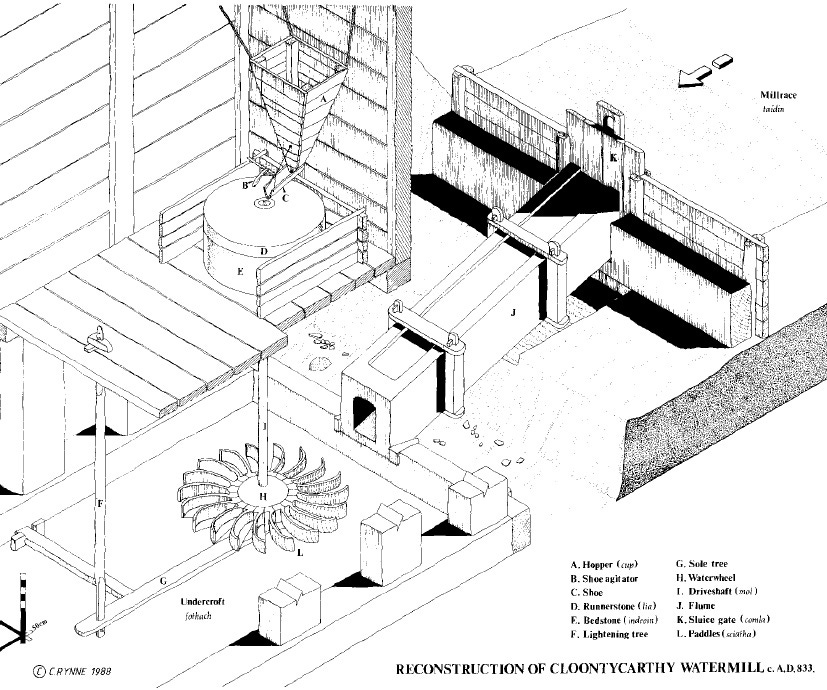

As the reconstruction below by Colin Rynne shows, water from the mill-race was directed on to the wheel via a wooden flume, and the pressure on the wheel drove a vertical shaft that turned the top millstone against the bedstone, grinding corn that was funnelled in through a hopper.

This is in fact the simplest type of water-mill, lacking the gearing systems of the more complex vertical-wheeled mill. And that was something that also piqued my interest. In Ireland, these horizontal mills are extremely old, dating far back into the early medieval period.

Rynne’s plan above is based on the remnants of a mill found at Cloontycarthy in Co. Cork and dendrochronologically dated to c. 833 AD. And it’s by no means the oldest water-mill in Ireland: archaeologists found a tide mill at Nendrum on Strangford Lough in Co. Down that dates to 619 AD.

These types of mills were not invented in Ireland: horizontal water-wheels were used to convert water into energy in ancient civilizations from Greece and Rome to India, China and southwest Asia. Indeed, in the early first century AD, Chinese hydrologist Du Shi is said to have been the first to use a horizontal waterwheel to power a blast furnace hot enough to forge cast iron.

But they certainly seem to have proliferated in Ireland in the later first millennium—153 early medieval mills have been found in Ireland so far—and they’re seen by scholars like Professor Wendy Davies of University College London as evidence for economic growth and diversification in the period, linked to the spread of monasticism.

An early medieval mill in Kinloss?

Basically, the humble horizontal mill is an interesting indicator of social and economic change, and I was pretty excited to have found a mention of one in my research area.

I was especially interested to note that the piece of land given to Kinloss Abbey wasn’t one with a working mill, but one on which the “Scottish mill used to stand,” suggesting an old, demolished mill.

This, combined with the examples from Ireland, seemed pretty exciting. Had I found evidence of an early medieval water-mill at Kinloss? Could it be connected to a lost early medieval monastery? Could it even be contemporary with Sueno’s Stone?

Down the rabbit-hole: first stop, Portmahomack

And so began a long—and so far fairly frustrating—journey. I asked my archaeologist friends on Twitter, months ago now, when Twitter was still just about usable and I was still on it and it was still called Twitter, what evidence there was for early medieval water-mills in north-east Scotland.

I wasn’t expecting to hear that there was none whatsoever, but that was the answer I got. Not a single pre-1124 water-mill has been found in Moray, or anywhere else in the north-east.

[UPDATE 16th Oct: It's not in the north-east, but thanks to Adrián Maldonado for drawing my attention to this single paddle from a horizontal water-wheel at Dalswinton in Dumfriesshire—a really nice example from 640 - 854 AD.]

Not really believing this, and thinking that the most likely location for a water-mill would be near a monastery, I went off to look at the write-up of the extensive archaeological dig carried out between 1994 and 2014 at Portmahomack in Easter Ross, led by Professor Martin Carver of the University of York.

Portmahomack was a sophisticated Pictish monastery that was destroyed by fire around 810 AD, but which prior to that catastrophic event had been producing exquisite stone sculpture, fine metalwork and—given the finds related to vellum working—probably illuminated manuscripts as well.

Surely, given that there was a sizeable, diversified and technologically-adept community here, almost certainly with links to Ireland and continental Europe, the monks of Portmahomack weren’t grinding corn by hand?

This was also the expectation of the archaeologists, especially when they discovered evidence of extensive water management on the site, including culverts, a dam, a pool, and a bridge.

The dam in particular looked like it could have been intended to build up a head of water for a mill, although the archaeologists found no evidence of anything specifically mill-related:

The interpretation as a dam, pool, road and bridge was based on the observed structures and the absence of any flume, paddles, penstock, wheel, wheel pit, bearing or millstones.

Despite none of these diagnostic features being present, the team did do some back-of-an-envelope calculations to see if a mill could have been inserted into the arrangement:

Analysis was carried out on paper to discover if the dam area could have concealed a penstock and wheel pit with sufficient head of water to drive it. This was found to have been technically possible…

Aha!

However, there was no trace of a wheel pit in this position nor of an outflow at the level of the natural subsoil. If there was once a mill in this position, it must have been thoroughly dismantled.

Oh.

After mulling the possibility that a mill could have been located further downstream (but finding no evidence there either) and noting that the monks of Portmahomack seem to have eaten more meat than bread in any case, the team reluctantly concluded:

It is concluded for the present, and with a weather eye on future discoveries, that milling technology did not reach Portmahomack at the same time as the other monastic skills, or was not needed if it did.

So no eighth-century mill at Portmahomack (at least, that we know of).

An early medieval mill on Iona?

What about that other very famous and extensively excavated early medieval monastery in northern Scotland: the one founded in 563 AD by St Columba on Iona?

We have a huge amount of incidental detail about daily life at the monastery from its ninth abbot, Adomnán, who wrote his Life of Columba there towards the end of the seventh century.

So does Adomnán mention a water-mill on the site—either in Columba’s time or his own? Well, yes and no. He never mentions the existence of a mill, but he does say at one point in Book 3 that:

After this the saint [Columba] left the barn and made his way back to the monastery. Where he rested halfway, a cross was later set up, fixed in a millstone; it can still be seen today at the roadside.

Unfortunately, that’s not as conclusive as it might seem. An extended footnote by the editor of the Penguin Classics edition of Adomnán’s Life of Columba, Richard Sharpe, comments:

On the use of the millstone as a cross-base, Anderson and Anderson1 suggest that this was a wooden cross fixed in the hole on the upper side of a hand-quern… but it should be said that such a hand-quern would not support even a wooden cross more than two or three feet tall.

So perhaps Adomnán is talking about a millstone from a water-mill? Sharpe thinks not:

Table-mounted querns, both stones pierced by a spindle, are known from early medieval contexts, and these may be up to three feet in diameter. A stone of this kind could support a rather taller cross, held in the socket with wedges.

Sharpe seems to think that this kind of tabletop hand-quern is likely the type of millstone meant, as the sixth century (Columba’s time) was too early for horizontal water-mills:

Actual mills, powered by a horizontal water-wheel on a vertical axle, were in use in Ireland by the seventh century; these could be larger, but clear evidence is not available from the sixth century.

It is generally thought, though, that Adomnán’s writing reflects the daily rhythms and activities of the monastery of his own day rather than Columba’s, and he was writing 100 years after Columba’s death. We know Ireland had mills in the seventh century, so could there have been one on Iona too?

Excavations at Iona’s mill stream

This is where the archaeological work carried out on Iona comes into play. In 1991, Jerry O’Sulllivan led an excavation beside the suggestively-named Sruth a’ Mhuilinn (Mill Stream), to see if an early mill could be identified.

And here, just beside Burnside Cottage, where the Sruth a’Mhuilinn passes through the monastic vallum (encircling ditch), the team discovered something interesting:

Excavation of Area 7 revealed a large sub-rectangular basin or man-made pool, cut to intersect the present course of the stream.

On further investigation this man-made pool proves to be accompanied by post-holes, suggesting the existence of some kind of building, and by seemingly artificial channels in the stream. Specialist plant and pollen analysis reveals a number of cereal grains, including wheat, oat and barley.

Is this an early medieval mill at last? O’Sullivan’s conclusion initially looks positive on that front:

[T]he unusual stream-bed location of these features invites the attempt to interpret the pool-basin and its associated post-pits as the site of a water-mill, and in particular as an example of the predominant pre-industrial type in the Scottish Highlands and Islands: the horizontal mill.

Unfortunately, though, none of the defining features of an Irish-style horizontal mill are present: no mill-house, no hopper, no millstones, no drive shaft, no timber undercroft, no water-wheel, no flume. And the plant and pollen experts aren’t convinced there are enough cereal remains to indicate a mill.

With only the pool-basin to go on, O’Sullivan is unable to reach a definitive conclusion. Without ruling out the possibility of an early medieval mill elsewhere on the island, he eventually leans towards the basin being the remnant of an early modern mill that a visitor to Iona, Thomas Pennant, saw in ruins on the same spot in 1772:

The available evidence points to the greater likelihood that Area 7 is the site of a modem mill. It is improbable that [Pennant] would have seen mill ruins which had endured since the medieval or Early Christian period. More likely, the structure [he] described had recently been abandoned, shortly to disappear, and was a mill established in the late 17th or early 18th century.

So no definitive early medieval mill on Iona either.

Conclusion: No mills, many questions

With that, my investigations have come to a disappointing close, at least for now. To the best of my knowledge, no early medieval water-mills have ever come to light in northern Scotland, and the age and nature of the demolished ‘Scottish mill’ mentioned in Bishop Richard of Moray’s 1187 confirmation charter to the monks of Kinloss Abbey remains a mystery.

If there truly were no water-mills in north-east Scotland prior to 1124—the accession of David I and the start of the high medieval period—it makes Scotland a strange outlier in European terms.

As we’ve seen, Ireland, which is probably the most comparable region to northern Scotland in the period, was using water-mills from the seventh century onwards, with 153 early medieval sites discovered so far. In France, the monastery of Montier-en-Der alone had 11 mills in 845 AD, according to Jean Gimpel’s 1976 book The Medieval Machine. And in England, Gimpel tells us, the Domesday survey of 1086 records the existence of 5,624 water-mills; one for every 50 households.

This isn’t a subject for just now, but this does raise many questions about why north-east Scotland seems to have been mill-free in this period. Have the mill sites just not been found, or have their remains just not been preserved? Was the staple diet meat rather than cereals? Was there no arable farming beyond subsistence farming? Was all grinding of flour done by hand—and if so, was it done by individual household, or by enslaved people for the community?

As ever, I’d be grateful for anyone’s thoughts in the comments.

References

Adomnán of Iona. Life of St Columba, translated and edited by Richard Sharpe (1995)

Carver, Martin, et al. Portmahomack on Tarbat Ness: Changing Ideologies in North-East Scotland, Sixth to Sixteenth Century AD (2016)

Davies, Wendy. Economic Change in Early Medieval Ireland: The Case for Growth, in England and the Continent in the Tenth Century: Studies in Honour of Wilhelm Levison (2011)

Gimpel, Jean. The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages (1976)

Miller, Alexandra. Early medieval Irish watermills (2015)

O’Sullivan, Jerry, et al. Excavations beside Sruth a' Mhuilinn ('the Mill Stream'), lona (1995)

Rynne, Colin. Archaeology and the Early Irish Water-Mill (1989)

Rynne, Colin. The Craft of the Millwright in Early Medieval Munster, in Early Medieval Munster: Archaeology, History and Society (1998)

Rynne, Colin. The Technical Development of the Horizontal Water-Wheel in the First Millennium AD: Some Recent Archaeological Insights from Ireland (2015)

Stuart, John. Records of the Monastery of Kinloss (1872)

Anderson, Alan O. and Marjorie O. Anderson, Adomnán’s Life of Columba (1961)

There are traces of, an references to, a very old tidal mill in Munlochy, down at the waters edge below Bayhead Farm.

Was Moray just too flat?

"The distribution of the horizontal mill in Scotland covers the Northern Isles, Caithness and Sutherland, the Hebrides, Mull, the Kintyre peninsula and also Galloway, to judge by the find of a scoop-shaped paddle there. They also appear in the Isle of Man, and in Ireland, as already mentioned. They are indeed a worldwide phenomenon, except in very flat areas where there is no run of water to drive them."

(Fenton & Veitch (eds.): Scottish Life and Society: Farming and the

land ,p. 745-6)