Was there an earlier Pictish monastery on the Kinloss Abbey site?

In which I test Neil McGuigan’s theory that there was an early medieval monastery near to—and connected with—Sueno’s Stone

In my last blog I mulled the idea that there might have been an earlier ecclesiastical foundation on the site of Kinloss Abbey near Forres in Moray, Scotland.

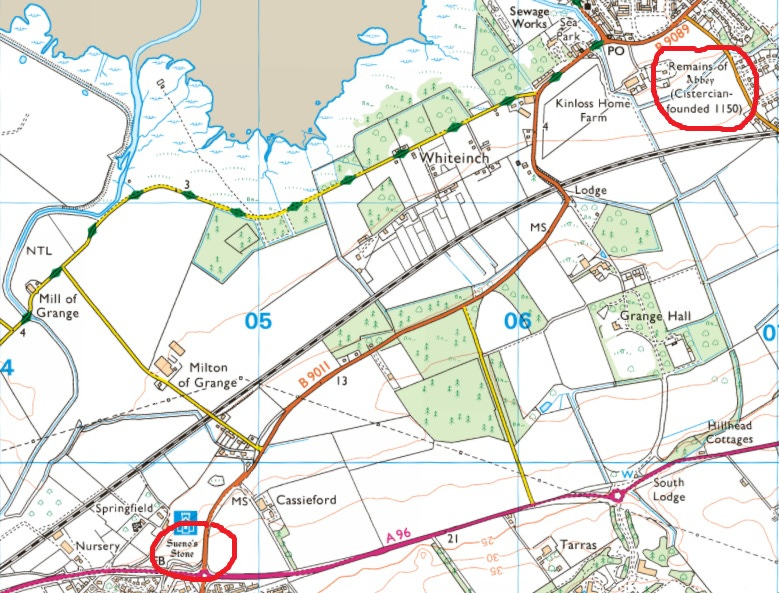

It’s a question I want to look at in more detail in this blog, as part of my MA research into Sueno’s Stone, an enormous early medieval cross-slab that still stands in its original spot, 3.5km south-west of Kinloss Abbey.

On the face of it, these two sites aren’t related. Art historians believe Sueno’s Stone was raised no later than 950 AD, while Kinloss Abbey was founded by David I of Scotland in 1150.

But in the first chapter of his biography of Máel Coluim III (Malcolm Canmore), Dr Neil McGuigan briefly floated the idea of an older monastery on the Abbey site. While setting the scene for Malcolm’s accession to the Scottish kingship in 1058, he wrote:

Forres hosts one of the largest and most impressive pieces of monumental sculpture to survive from pre-Norman Britain, Sueno’s Stone, possibly erected in the tenth century. […] In the twelfth century, after a failed bid by Áengus mormaer of Moray to install Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair as king, the victorious David I took direct control of Áengus’s land and founded a Cistercian monastery near Forres, Kinloss Abbey. Situated on the edge of such an important Viking Age centre it is likely that Kinloss Abbey’s Cistercians took over from an earlier monastic house, perhaps one of Pictish origin. [my emphasis]

This got me thinking: how would I establish whether there was ‘an earlier monastic house, perhaps one of Pictish origin’ on the site of Kinloss Abbey, which might have been connected with Sueno’s Stone?

So in this blog I’m going to assemble as much evidence from different sources as I can, and see if it’s a viable proposition.

Archaeological evidence

First off, there’s no existing archaeological evidence for an earlier monastery on the Kinloss Abbey site. However, as far as I know, the site has never been excavated or even geophysically surveyed.

The nearest thing I’ve seen to an archaeological survey is this aerial photo of cropmarks adjacent to the abbey, taken during the hot summer of 1976. These marks don’t appear on aerial views on the current Google Maps or the Ordnance Survey site, and early maps of Kinloss Abbey don’t show any other buildings to the east or southeast of the present abbey precinct.

One of these marks, outlined in red above, appears to be neatly rectangular, and one of its short sides abuts on to the Kinloss Burn, which is straight at this point and therefore artificially channelled. To me, a neat rectangle abutting on to a straightened burn is just far too neat to be an indicator of an early medieval site, so I’m going to let it go.

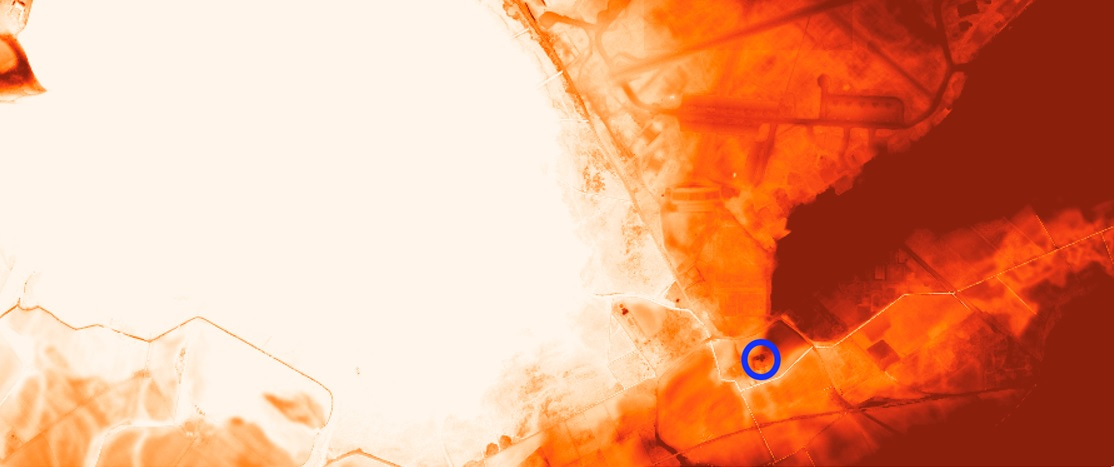

The other mark, immediately to the east of the abbey and outlined in blue above, is less clear, but it seems to be an open-ended sub-rectangular shape. But I’m not an archaeologist, and I have no way of telling what, if anything, this might suggest. The only observation I can make is that this mark, like the abbey itself, is on the spur of slightly higher ground revealed in the LiDAR image below:

But otherwise, that’s the end of the cropmark-based investigation for me—at least for now.

Sculptural evidence

On to sculpture. If there were a Pictish monastery at Kinloss, especially one with a high-status patron, we might expect fragments of early medieval carved stone to have turned up—through ploughing of the surrounding fields, or incorporated into the abbey walls and foundations, or just lying around on the abbey site. This is how other early medieval ecclesiastical sites in the Moray Firth area, like Kinneddar and Portmahomack, first came to light.

To date, though, there have been no early medieval sculpture finds at or around Kinloss Abbey (unless you count Sueno’s Stone itself, but that is getting into the realms of circular argument).

I did get quite excited last year at news of the discovery of a fragment of early medieval cross slab in Kinloss, but it turned out it was actually found at Findhorn, and it seems likely to have found its way there from Kinneddar as it’s stylistically similar to a cross-slab fragment from that site.

This isn’t necessarily a deal-breaker, as not every early medieval ecclesiastical site seems to have had stone sculpture. Not too far from Kinloss are two church sites, Birnie and Barevan, with no early Christian sculpture (although Birnie does have a non-Christian Class I symbol stone).1 But we know they’re early medieval because they both turned up iron hand-bells of a kind that are particularly associated with the Columban church, and which are dated to 600-800 AD.

However, there’s no suggestion of an iron hand-bell at Kinloss either, so this line of enquiry draws a blank.

Textual evidence

So much for archaeology—what about textual evidence? (I am training to be a historian, after all.) Is there any suggestion in the early records that there might have been a religious establishment at Kinloss prior to the founding of the abbey in 1150?

Well, there’s the fact that some versions of the medieval Scottish king-list say that say king Dubh of Alba was murdered in Forres in 966 or 967 AD and his body hidden ‘under the bridge at Kinloss’. The ‘D’ king-list, for example, says:

Duf macMalcolm iiii a. reg. et mensibus sex et interfectus est Fores et absconditus est sub ponte de Kynloss et sol non apparuit quamdiu ibi latuit et inventus est et sepultus in Iona insula.

Duff macMalcolm reigned for four years and six months, and he was killed in Forres and hidden under the bridge of Kinloss, and the sun did not appear while he lay hidden there, and he was found and buried on Iona.

If this did actually happen (and it’s interesting that there was indeed a solar eclipse in 966), it would be good evidence for a bridge at Kinloss in the tenth century. And as early medieval wooden bridges had to be continually maintained, it’s not unreasonable to assume that this maintenance work might have been done by a nearby monastery.

Historians believe this was the case at Clonmacnoise in Ireland, where a ninth-century wooden bridge over the River Shannon was likely maintained by the community that had grown up around the monastery there.

But there’s a problem. The medieval Scottish king-lists date from the twelfth century at the earliest, so we don’t know how accurate they are in their account of Dubh’s death in 966/67.

Frustratingly, the one surviving tenth-century manuscript source, the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, breaks off its narrative while Dubh is still alive, and only resumes with the accession of the next king, Cuilén. Although it says Dubh was ‘expelled from the kingdom’, it doesn’t say where he went or how he died. If it had, it could have been by far the earliest historical mention of both Forres and Kinloss.

I think there’s a faint glimmer here, all the same. Kinloss Abbey was founded in 1150, allegedly on an undeveloped site. But Professor Dauvit Broun, after spending years tracing the medieval king-lists back to their earliest sources, established that the lists that mention Dubh being hidden under the bridge at Kinloss derive from a source written in 1124, twenty-six years before the abbey was founded.

Could this mean there was already a monastery at Kinloss, with a bridge, that David I took over in 1150 and re-granted to the Cistercians? It’s tenuous in the extreme, but it’s something. And in writing this, I’ve remembered that Professor Archie Duncan had a theory about where the weirdly-specific story of Dubh’s murder and concealment had come from:

These events must have been made the subject of some long-lost Gaelic epic or lament, of which we hear an echo in a brief Latin annal telling that Dubh lay slain under the bridge of Kinloss and that the sun did not shine until his body was recovered for burial.

So, in Duncan’s opinion, a fragment of an older poem about Dubh had found its way into a king-list written in 1124. If true, this would indeed suggest that ‘Kinloss’ and its bridge were in situ before the Abbey was founded in 1150. But otherwise, I think that’s it for the written sources for now.

Contextual evidence

It’s possible to add a bit more weight to the idea of an earlier monastery from what we know about David I’s activities in Moray. The Kinloss Abbey foundation legend says it was built in a clearing in the forest where David had been given shelter by shepherds after getting lost while hunting. While there, he had a vision of the Virgin Mary, inspiring him to found an abbey in her name in that place.

But historians are sceptical of this, as it’s very similar to the foundation legend of Holyrood Abbey, another David I foundation. And while David was undoubtedly very pious, he was primarily a political strategist. In his 2004 biography of David, Professor Richard Oram saw the foundation of Kinloss Abbey not as a divinely-inspired act of devotion, but as part of a calculated and multi-pronged strategy to impose control on this distant and unruly northern province of David’s kingdom.

The colony [of Cistercians] was planted in a highly strategic location in the Laich, close to the second of the king’s new strongholds at Forres.

Moray had a tendency to produce rebels and pretenders with reasonable claims to the throne; a trend David was keen to suppress.

One such rebel, Óengus mormaer of Moray, was killed by David in 1130, and although there’s no textual evidence, historians like Oram think it likely that David seized control of Óengus’s lands and re-granted them to his political and spiritual allies, like the Cistercians.

Nobody knows where Óengus’s lands actually were, but it’s possible that Kinloss was part of his territory, and thus perhaps home to an earlier religious establishment of which Óengus was patron. This is what Neil McGuigan was suggesting in the quote that started me off on this enquiry:

David I took direct control of Áengus’s land and founded a Cistercian monastery near Forres, Kinloss Abbey. Situated on the edge of such an important Viking Age centre it is likely that Kinloss Abbey’s Cistercians took over from an earlier monastic house, perhaps one of Pictish origin.

Place-name evidence

On this note, the place-name ‘Kinloss’ itself may be of interest. I’m only at the start of my investigation into this, so I’m not going to come to any conclusions in this blog. But I think there are a couple of things to note for further follow-up.

Firstly, it’s plainly a Gaelic name, with its first element ‘kin’ an anglicised spelling of Gaelic ‘ceann’, or ‘head’. The second element is less certain, but the Scottish place-name scholar W.J. Watson saw it as Gaelic ‘lois,’ meaning ‘herbaceous’, or perhaps ‘meadowy’.

This would make Kinloss the ‘meadowy headland,’ which fits well with the LiDAR image above showing the abbey on the tip of a spur jutting into lower-lying land that might well have been salt marsh or tidal estuary in the middle ages.

Is the fact that it’s a Gaelic name significant? Kinloss Abbey was founded by David, a primarily English-speaking king who had been brought up in Norman England. And it was seeded with monks from Melrose in the Scottish borders, formerly part of the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria.

How likely is it that this culturally English founder team would have given a brand-new abbey a Gaelic name? Might it suggest that there was a culturally Irish/Gaelic establishment here previously? I don’t know, and the fact that the name refers to a landscape feature means it could have been named ‘Kinloss’ by Gaelic-speaking locals without necessarily having anything built on it.

But the name Kinloss does help me to think about whether a possible ‘earlier monastery’ on this site was ‘one of Pictish origin’. Historical mentions of the Picts fade out around 900 AD, 250 years before Kinloss Abbey was founded. In the intervening period, place-name and personal name evidence suggests that Moray was heavily Gaelicised, with more of an Irish character than a Pictish one.

So while it may turn out to be just possible to argue that Kinloss Abbey was a re-foundation of an existing Gaelic monastery, making a case for that monastery being ‘one of Pictish origin’ would be near-impossible without archaeological investigation, I think.

This is as far as I can take the historical and place-name evidence at the moment, but I may be able extract more in future by reading more about David I (although Richard Oram’s new biography of David is punitively expensive) and about Cistercian foundation strategies. One to come back to, I think.

Landscape evidence

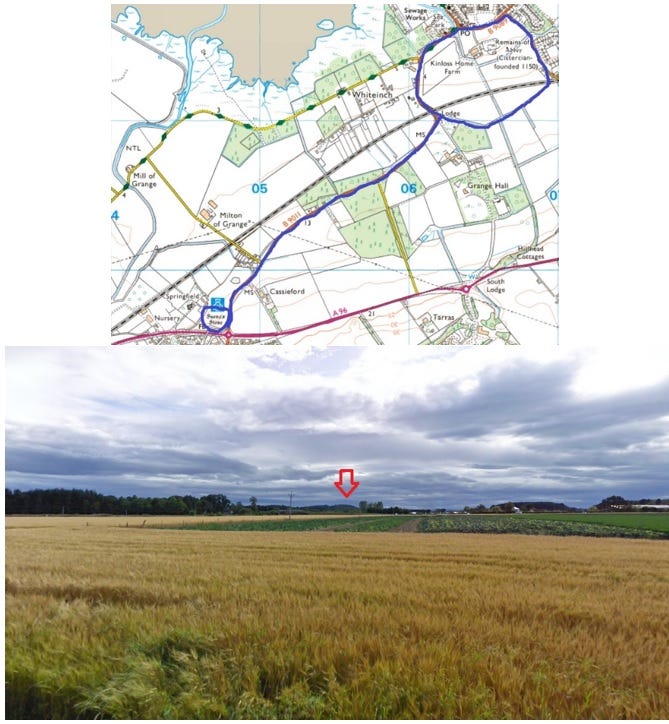

So lastly for this blog, there’s one final source I can tap: the actual landscape around Kinloss Abbey. I looked at this at the end of my last blog, and noted a strange feature that seems to encompass the abbey site. It looks like the line of a very large, curvilinear ditch or enclosure of some kind:

I have no idea what this feature is, whether it belongs to the twelfth-century abbey (or later), or if it’s earlier. If it is earlier than the twelfth century, much of the land it encircles would have been very soggy, or even tidal estuary. So I’m at a loss to explain what it is, or if it’s relevant to my investigation.

UPDATE:

But as I mentioned last time, it is perhaps notable that this feature is at the end of a short stretch of road (the modern B9011) that begins at Sueno’s Stone. And it’s perhaps also notable that if you stand at the edge of the abbey site and look south-westwards over the feature (which is now fields) and along the line of the road, you clearly see Forres and the site of Sueno’s Stone in the distance.

Does this mean anything, or am I just saying ‘look, you can see one place from another place’? I don’t know, and maybe I never will. But I’ll keep this thought on file, just in case it becomes useful.

In conclusion: ‘Maybe’

So having gone through all the evidence at my disposal, and using as many techniques as I’m currently able to, can I answer the question of whether there was an earlier monastic house, perhaps one of Pictish origin on the Kinloss Abbey site?

Well, I can certainly give an answer, and that answer is ‘possibly’. I think there’s enough in the aerial photography, primary textual sources, contextual historical sources, place-name evidence and landscape evidence to suggest there was something—and something that had a bridge—on this site before the abbey was founded in 1150.

But whether it was an earlier monastery of any kind, let alone one of Pictish origin, is much harder to say. As always, if anyone would like to pitch in with any suggestions, I’d love to hear them!

References

Cormac Bourke, “The hand-bells of the early Scottish church,” Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 113, 1983.

Dauvit Broun, The Irish Identity of the Kingdom of the Scots, Boydell Press, 1999.

A.A.M. Duncan, “The Kingdom of the Scots” in The Making of Britain: The Dark Ages, LWT and Channel 4, 1984.

Neil McGuigan, Máel Coluim III Canmore: An Eleventh-Century Scottish King. Birlinn, 2021.

Richard Oram, David I: The King Who Made Scotland, Tempus, 2004.

Aidan O’Sullivan and Donal Boland “Clonmacnoise Bridge,” University of Memphis Department of Civil Engineering.

W.J. Watson, The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland, Birlinn, 2011.

Alex Woolf, From Pictland to Alba 789-1070, Edinburgh University Press, 2007.

Re-reading the Canmore entry for Birnie, there is also a mention of there having been four fragments of Class III cross-slab preserved within the church, but it seems they are no longer there and I haven’t yet found a description of them. But perhaps we can say there was early Christian sculpture at Birnie after all.

An interesting question again Fiona! I can’t answer this question either but here’s a few points to consider? The first question is: what is the definition of a monastery versus a church or chapel at this period? It's difficult to define, but I’d suggest a monastery is a centre where several monks are permanently housed and crafts and agriculture undertaken, while a church might just be manned by one person or by itinerant monks from a nearby base. So I think your question should be broken into two – Was there a Pictish monastery here? And secondly, was there a chapel here? The answer to the first is almost definitely no, as you point out, most large churches and monasteries in Pictland do have evidence of carved stones, and most of them seem to continue on into historical times. But more critically, monasteries were major royal patronage centres, given political protection and voted a lot of resources, and they wouldn’t normally be established so close together, as Kinloss and Kinneddar. The only possible scenario might be if Kinloss was a female nunnery partnered with a male group at Kinneddar, but that’s pure speculation, no evidence for it.

But was there a chapel at Kinloss? I think the jury is out on that one, because there is that fragment, waterworn, but I’m struggling to see it having moved under its own steam from Kinneddar, it’s more likely to be from a chapel somewhere in this Kinloss area. This is supported by the other small memorial stone at Achareidh, which is possibly another small church, both of them governed by Kinneddar. (The same pattern is seen in the south too, where there is a definite centre for carving and burials, but one or two at outlying chapels). But then, if there was a small chapel somewhere near Kinloss, then it’s going to be dated between four or five centuries before the later monastery, and with all the chaos of the Viking years between, so I’m not sure it’s easy to draw a direct line between a possible small chapel of no note and the later monastery half a millenium later, even if they were on the same spot.

Hi Fiona,

Usual post blog post musings…..

I would support your view that there was an earlier church at Kinloss as this was the case with most of the other abbeys. Think Jedburgh, Melrose et al. The most important thing to incoming monks was not immediate building but where could they undertake their primary function, the glorification of God, whilst they were building their model church? Thus they needed a pre-existing church to be at hand.

On Kinloss etymology, I’ve never bought the traditional foundation story as it always struck me as an example of “sounds like” etymology (King lost/Kinloss).

Another alternative I have pondered is whether the Loss that we’re at the head of is the Loxa/Lossie? That river has wandered quite far over the years and certainly ran into Spynie Loch at one time. The Loxa/Loch may well have extended as far west as Grange Hill/Miltonhill , emptying into Findhorn Bay with Kinloss Burn being a vestige of what was once a much greater water channel

Just my tuppence worth as usual

Keep it up!