An early Christian burial ground at Knockando?

In which I go in search of the lost early medieval ecclesiastical site of ‘Pulvrenan’

[UPDATE 17/12: Following feedback I’ve made a couple of corrections to this post and added two three footnotes regarding the ‘rune-carved’ stone found at ‘Pulvrenan’. These don’t affect the main enquiry.]

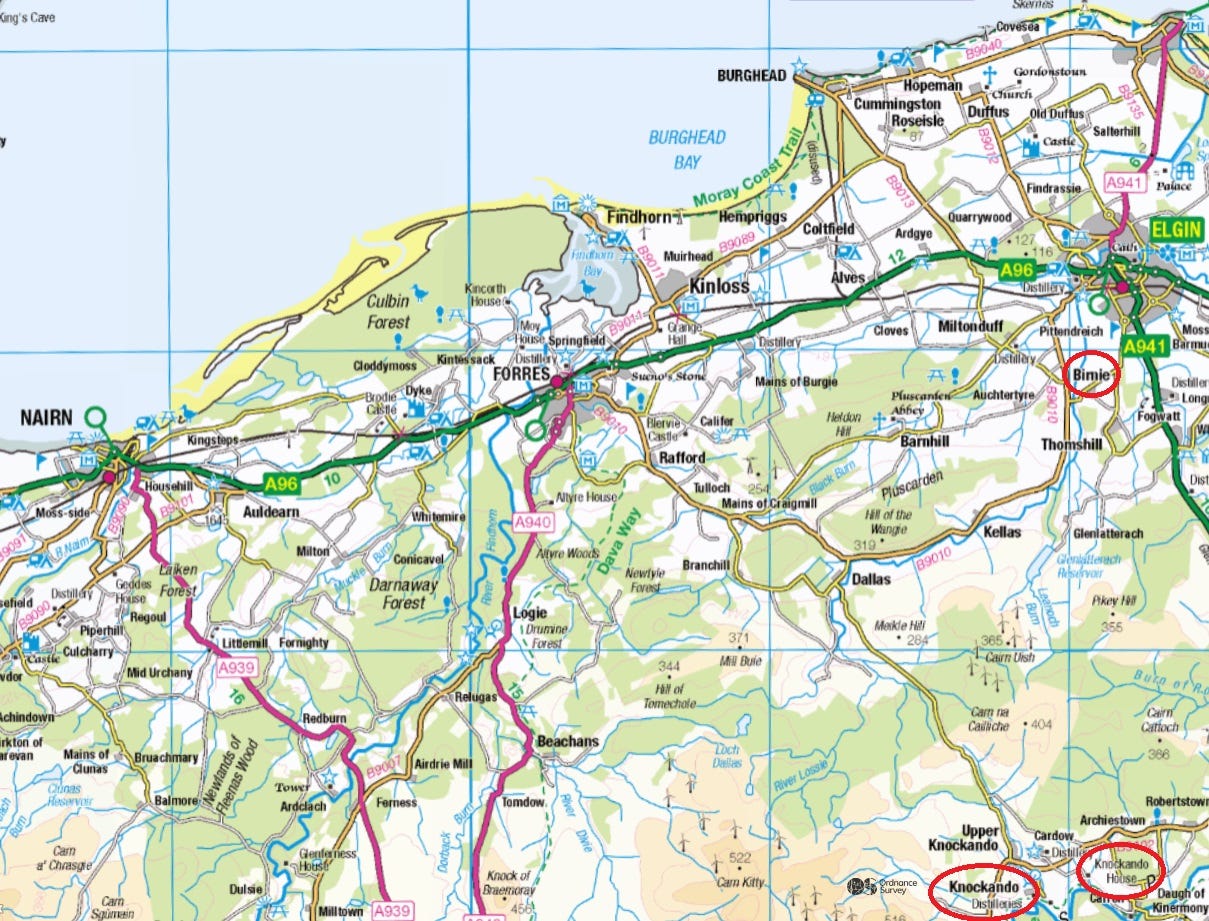

Ever since I started this blog, I’ve been writing about the part of Scotland that I know best: the coast and hinterland of the Moray Firth between Inverness and Lossiemouth; the area where I grew up.

My plan was to apply the skills I’ve been learning on (and off) my MA course to places and objects that I know very well. I figured that once I’d learned the ropes, I could start digging into the early medieval history of parts of Scotland that I know less well, or not at all.

By now I’ve built up a good stock of research techniques, primary and secondary sources and expert contacts that I can draw on to investigate the ‘rabbit holes’ of this blog’s title.

So when Helen McKay of Pictish Puzzles and Cryptic Celts asked a question on Facebook about a supposed lost early Christian church site at Knockando, a Speyside village in upland Moray, it felt like a great opportunity to test them out.

A cult of St Brendan in upland Moray?

In fact, Helen’s initial question wasn’t about Knockando, but about the ancient church of Birnie, just south of Elgin. It’s connected to Knockando by an old routeway called the Mannoch Road, and there’s a whisper of a cultic connection too, as both places are said to be dedicated to Brendan the Navigator; a sixth-century Irish saint famed for his seven-year voyage to find the Isle of the Blessed.

Helen asked:

I have a question about the dedication of Birnie. It's said to be dedicated to St Brendan, but for some reason academia doesn't seem to accept that, and there is no saint at all given in the Scottish saints database. So would anyone known what is behind this rejection?

Academics Alex Woolf and Gilbert Márkus replied that the dedication has been inferred from early forms of the name Birnie—like Brennath and Brennach—which are superficially similar to ‘Brendan.’ However a church would never just be given the name of the dedicatee; it would be given a name meaning ‘Brendan’s church,’ like the similarly-named Kilbirnie in Ayrshire.

A church dedicated to St Brendan at ‘Pulvrenan’?

I thought I’d seen another reason for the rejection, and this is where I fell down the rabbit hole. On the excellent Saints in Scottish Place-Names database that Helen mentioned, the supposed dedication to Brendan at Knockando (not Birnie) is dismissed as follows:

While the name form in 1867 may plausibly represent a Brendan dedication, the fact that this place is far from the sea, and that Brendan dedications are almost all on the sea-shore or on islands, may cast doubt on the saint being commemorated here.

The name form being referred to here isn’t Knockando but ‘Pulvrenan,’ a place-name that has become strongly associated with a supposed lost early medieval church site, dedicated to St Brendan, on the northern bank of the Spey below Knockando House.

To show you what I mean, here’s an excerpt from a 1973 survey of early ecclesiastical sites in Scotland published in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, documenting this apparent lost site:

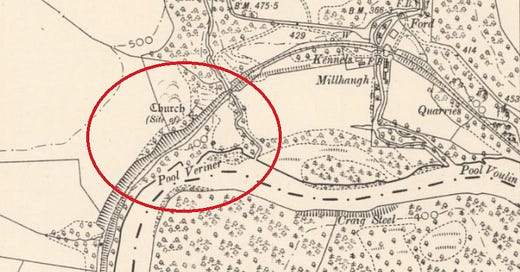

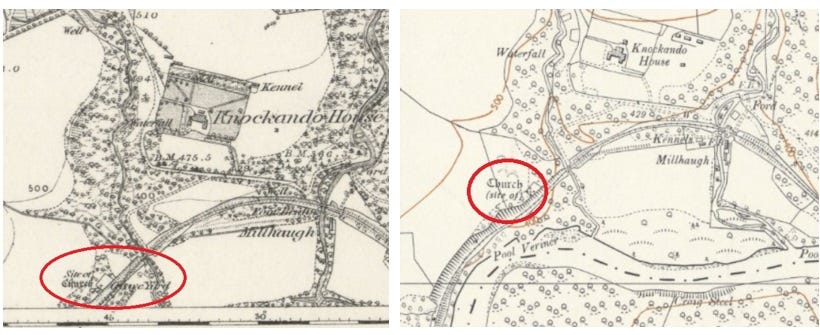

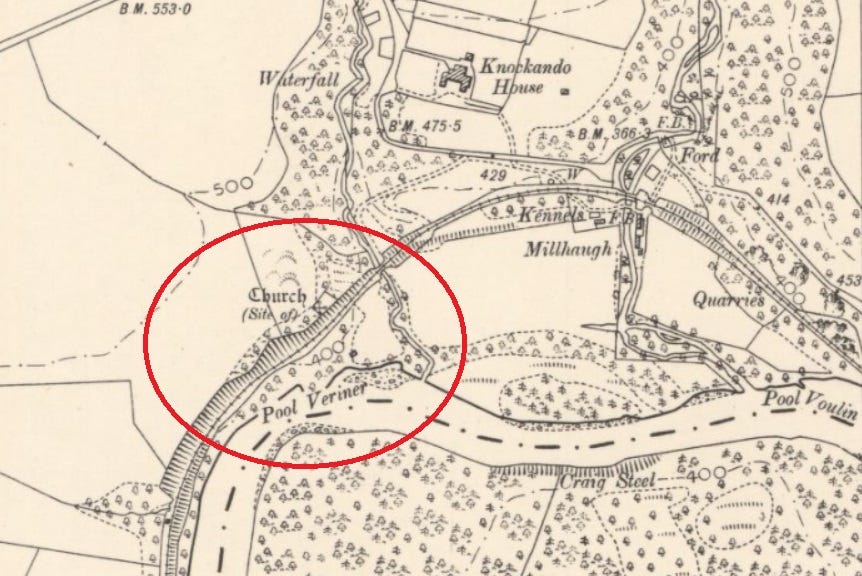

Similar information is included in Historic Environment Scotland’s CANMORE database, as well as on older Ordnance Survey maps like those from 1871 and 1905 below, compounding the idea of a lost church dedicated to Brendan at ‘Pulvrenan’.

Tracking down the origins of ‘Pulvrenan’

A big strand of my MA research is around lost early medieval church sites, so this piqued my interest. In particular, I wanted to understand how ‘Pulvrenan’ had been identified as an early Christian site, to see if those methods could help me identify other potential sites in Moray.

I thought this might be a fairly straightforward bit of information-gathering. Instead, I found a tangled clump of folk-memories, tenuous associations, circular logic and embellished facts, all formed around a single, unsourced statement written sometime in the mid-1860s.

Untangling it all has meant digging into newspaper cuttings, lists of church ministers, nineteenth and eighteenth-century statistical accounts, seventeenth-century chancery records, medieval charters, cartographical surveys, maps going back to the sixteenth century, works by amateur and professional historians, articles in learned journals, personal reminiscences, and the history of the Great North of Scotland Railway. (I even came across an unsolved nineteenth-century murder!)

After all this, I can see how the idea of an early Christian site dedicated to Brendan at ‘Pulvrenan’ came about. However, I can’t find any direct evidence for the actual existence of such a site—and certainly not as a place of Christian worship and burial, with or without a dedication to Brendan.

Where it all began: Sculptured Stones of Scotland (1867)

I’ve been deliberating about the best way to summarise all of this research, and I think maybe it’s an idea to start with the paragraph that kicked off all of the subsequent confusion.

It’s in Volume II of John Stuart’s Sculptured Stones of Scotland (hereafter SSS II), the first comprehensive survey to be made of ‘Pictish’ and other early medieval carved stones across Scotland.

Volume II came out in 1867 as a follow-up to the first volume published in 1856. It was prompted by a flurry of newly-reported carved stones—many of them doubtless discovered by antiquarians whose enthusiasm had been fired by the first volume.

Among the newly-identified stones featured in Volume II were two Class I incised Pictish symbol stones at Knockando Parish Church, where they still are today. A third stone reported along with them had no Pictish symbols, but it did have what appeared to be a runic inscription,12 3so Stuart included it too.

Here’s how they appear in the book (below left), and here they are in their current position built into the kirkyard wall (below right).

Stuart wrote up these discoveries in a short, three-paragraph entry:

Knockando is formed of the united parishes of Knockando and Macalen, and lies on the north bank of the Spey, above the well-known rock of Craig-Ellachie, which bounds it on the east. There are two or three places in the parish where chapels or religious houses are supposed to have stood.

The three slabs figured on this Plate are now placed in the graveyard of the parish, but are said to have been brought thither from an old burial ground called Pulvrenan, on the bank of the river below Knockando House, about fifty years ago [i.e. about 1815]. The stones are much weathered and are undressed.

The inscription on no. 3 is in runes. It has been read…as “SIKNIK.” Professor Stephens, to whom I am indebted for this fact, adds that the inscription at Knockando is in Scandinavian runes of the oldest and simplest form, and may date from the ninth or tenth century.” [my emphasis]

Deconstructing Stuart’s write-up

A few things are notable about the way the stones are covered in SSS II:

Stuart says a few places in the parish are ‘supposed to’ have been chapel sites, implying that memory of these sites resided in oral tradition rather than written record. He doesn’t explicitly say that ‘Pulvrenan’ is one of these sites, but a reader might easily infer that it is.

What he does explicitly say is that the burial ground is called ‘Pulvrenan.’ As we’ll see, this statement is responsible for seeding the idea that there was an early Christian church and burial ground in Knockando, dedicated to St Brendan.

Despite this, none of the three stones said to have been brought from the “old burial ground of Pulvrenan” have any Christian symbolism. Nor are they obviously grave-markers, although they are of the right size and shape to have been used as such.

Stuart doesn’t say how the information about the stones and the burial ground came to his notice. However, we know from his Preface to Vol I that his method was to send a reply-paid form to every parish minister in Scotland, requesting details of any sculptured stones on their patch. He adds that other antiquarians across the country soon joined in the hunt.

Nothing about his perfunctory account suggests that Stuart went from Edinburgh to Knockando to verify the information. In fact his first paragraph seems to be cribbed from the 1835 New Statistical Account, with the wording about the supposed chapel sites lifted verbatim from page 68. The middle paragraph seems to be the information he was sent by the person reporting the discovery, and the third paragraph summarises his subsequent correspondence with an expert in Norse runes.

In the middle paragraph, the passive voice in “the slabs are said to have been brought from an old burial ground called Pulvrenan” and the dating of this removal to “about fifty years ago” suggest that Stuart was reporting unverified information based on oral tradition.

The stones had apparently been in the graveyard of the parish church since around 1815, but nobody had reported them to Stuart for SSS Volume I.

Searching for ‘Pulvrenan’ in the records

So other than the unsourced information in SSS II, what evidence is there for “an old burial ground called Pulvrenan on the bank of the Spey below Knockando House”?

Try as I might, I can’t find a single instance of this name in Knockando parish, or even anything resembling it, prior to the appearance of Stuart’s book.

Places I’ve searched include:

Alasdair Ross’s 2003 PhD thesis ‘The Province of Moray, c. 1000–1230,’ which includes a parish-by-parish breakdown of names of individual pieces of land

The People of Medieval Scotland database: searchable charter records from 1093 to 1371

The 475 charters collected in the Moray Register, dating from 1203 to 1569

The Retours to Chancery for Scotland: seventeenth-century records of inherited properties

The Old Statistical Account (1792) and New Statistical Account (1835) for Knockando parish

The Ordnance Survey Name Book for Knockando parish (1868–1871)

The millions of pages of old newspapers searchable on Newspapers.com

Digitised maps of Moray from the sixteenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

Lachlan Shaw’s 1775 book History of the Province of Moray

William Rhind’s 1839 book Sketches of Moray

Watson and Watson’s 1868 book Morayshire Described

Ian B. Cowan’s 1967 book The Parishes of Medieval Scotland

There’s not a whisper of a ‘Pulvrenan’ in any of these sources, strongly suggesting that the first ever mention of it is the one in SSS II.

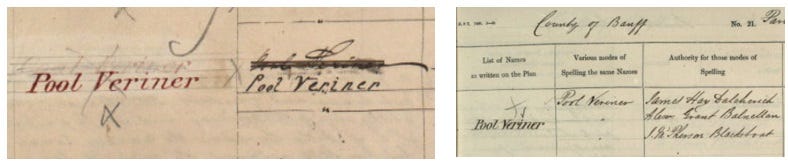

But what does emerge is a place-name that has become tangled up with the idea of an old church and burial ground called Pulvrenan: ‘Pool Veriner’.

Pool Veriner: an anglicised Gaelic name?

Pool Veriner is (or was) the name of a deep pool in the river Spey below Knockando House—exactly next to the spot where Stuart places the “old burial ground of Pulvrenan.”

Though clearly Gaelic in origin (as the noun ‘pool,’ from Gaelic ‘poll,’ appears first), its anglicised spelling was fully established by the late 1860s when Stuart was compiling SSS II. We know this beyond doubt, as it appears as ‘Pool Veriner’ in the Ordnance Survey Name Books for both Knockando parish on the north bank of the Spey and Inveravon parish on the south bank.

The Name Books are a detailed survey conducted from the 1840s to the 1870s, ahead of producing the first OS maps. OS surveyors visited every parish, collecting and verifying information about the names and spellings of places locally. Information for Knockando (then in the county of Elgin) was collected between 1868 and 1871, and for Inveravon (then in Banffshire) between 1867 and 1869.

Every single name—of hills, cottages, farms, bridges, burns, mills and many more features—is neatly recorded, with descriptive remarks and the names of local people who confirmed the name and spelling. The OS aimed to get three witnesses to each spelling, but for ‘Pool Veriner’ they actually got six: three in Knockando and three in Inveravon. You could hardly wish for a better-attested name.

But while the form ‘Pool Veriner’ is impeccably well attested, there’s no indication of what its original Gaelic name might have been. Gaelic had fallen out of everyday use in Knockando parish in the mid-eighteenth century, according to a report submitted in 1792 by Rev. Francis Grant for the Old Statistical Account, and the anglicised name seems to have been fully embedded by 1868.

I’m aware of four different Gaelic names that have been attributed to ‘Pool Veriner’ since 1867, though. The first is Stuart’s mysterious ‘Pulvrenan;’ a name not in use locally in the 1860s and not found in any source older than his own book. To my mind, this surely means it’s spurious. I can’t think where it must have come from: did his anonymous informant mishear ‘Pool Veriner,’ maybe?

Secondly, in November 1905, a John Milne of Aberdeen gave a talk to the Banffshire Field Club on The Place-Names of Strathavon. Although it’s not in Strathavon, Milne included Pool Veriner in his talk, giving it a supposed original name of Poll Baráin, or Baronet’s Pool.

This interpretation has the advantage of being drawn from the anglicised name, rather than from the spurious ‘Pulvrenan’. However, some of Milne’s other interpretations suggest that he was a man who knew some Gaelic and wanted to show it off, rather than someone with a deep grasp of onomastics.

His translation of the odd place-name ‘Phones’ is fionn-eas, ‘white-water,’ for example, whereas the place-name scholar W.J. Watson deduced from its early form Fotharáis that it means ‘terraced slope in a wood.’ So perhaps we shouldn’t set much store by Poll Baráin.

Thirdly, on the Early Church in the North of Scotland website there’s a wonderful evocation of late nineteenth-century Knockando written in 1955 by a John G. Shand, who left the village in 1900, aged 20, to join the London Police Service. He returns as an old man and records his impressions of his youthful haunts.

Shand’s family lived at Millhaugh, right next door to ‘Pulvrenan,’ so he knew the site intimately, although the stone or stones had been removed long before he was born. In 1955, he wrote:

As I leave the Churchyard I note the two old Scandinavian Tomb Stones – taken from an old Norse Graveyard near “Pool brenon” Millhaugh – are still to be seen set into the Churchyard Wall. They are relics of Centuries ago and deserve preserving for their very antiquity and as a reminder of the various activities of the Danes on the shores of our Country and elsewhere. [my emphasis]

Shand refers to the graveyard as being ‘near’ Pool brenon, rather than ‘Pool brenon’ being the name of the site itself, which he calls Millhaugh. He’s also put it in inverted commas, as if to stress that it’s not the name he would use, but a name other people call it.

To me this suggests that the name ‘Pulvrenan’ only took root in Knockando after SSS II came out and this is Shand’s phonetic reproduction of it, remembered from childhood in the late nineteenth century. In any case, Shand doesn’t associate it with a Christian site, as he believes the graveyard and the Pictish symbol stones to be Norse. (Oddly, he doesn’t mention the third stone with the actual Norse ‘runic’ inscription.)

Lastly, and significantly, in 1973 McDonald and Laing proposed an original Gaelic name of Poll Bhreunainn, or ‘Brendan’s Pool.’ This suggestion has been reverse-engineered from the surely-spurious ‘Pulvrenan’ and is the first instance I can find of the name being associated with St Brendan.

Their rationale for the Brendan interpretation seems to stem from the name ‘Pulvrenan’ having been repeated in Allen and Anderson’s highly influential Early Christian Monuments of Scotland, published in 1903, which says:

Knockando: - The church of Knockando is situated on the N. side of the River Spey, 3 miles N. of Blacksboat railway station. The two symbol stones are said to have been brought from the old burial ground at Pulvrenan on the bank of the Spey below Knockando House, and are now in the churchyard of Knockando.

From this point onwards, the notion of an Early Christian site at ‘Pulvrenan’ dedicated to St Brendan starts to gain currency—not helped by attempts to link the lost place-name ‘Aberbrandely’ or ‘Abberbrandolthin Brenin’ to the same site.

That’s a whole new rabbit hole, so all I’ll say is that the evidence all points to ‘Aberbrandely’ having been located south of the Spey in Inveravon parish, not north of the Spey in Knockando parish.

(For those interested, this theory was proposed by Cowan (1967 ) but debunked by both Barrow (1989) and Ross (2003); all three works in bibliography below.)

Sifting the evidence for an early church site

But was there really an early church site next to Pool Veriner—especially given that there’s nothing Christian about any of the three stones said to have come from here?

Here it’s instructive to look at the OS Name Book again, where the site in question is recorded in a series of three rather vague and confused entries on page 49.

The first entry reads:

CHURCH (Site of)

The tradition of the parish has it, that this was a Church and Church Yard Some 300 years ago - no record apparently is left to Support the tradition, nor is there left but a Meagre record about any of the old churches in the Parish, no portion of the Site is now visible on the ground, but the Surface about the place is ineven as if it were vestiges of the old graves.

It is Said all the grave Flags were taken away And the Railway Cutting Seems to have touched the South Side of the Grave Yard. Situated amongst old Trees upon the Main of a small promentory about 4 Chains Westward of where the Strathspey Section Railway line Cross the Cardnach Burn.

It is also Said that attempts were made to restore or rebuild the Church upon the Site in question and the opposing party got it removed to near the Site of the present Parish church – dedication name not Known. [my emphasis]

Next comes a record of:

GRAVE YARD

The Grave yard in connection with this building is Said to be Coeval with the same.

And finally we read of another (but actually the same) site:

SITE OF CHURCH

The site where the old parish Ch [Church] Stood, said to have been an ordinary building thatched with straw. the date is unknown, but is supposed to have been the first Christian place of Worship in the Parish. There are no visible traces now. [my emphasis]

There’s a lot here, but the main thing to note is that despite a local tradition of an old church and graveyard on this spot, these entries admit there is no written or physical evidence of such a site.

What’s more, the site isn’t given a name (although ‘Knockando Church’ is crossed out), so no ‘Pulvrenan.’ And the dedication of the supposed early Christian church is ‘unknown,’ so no sign of Brendan.

The first entry also notes that the Strathspey Railway—built between 1861 and 1863—had recently cut through the southern edge of the site. However, there’s no mention in the Name Book (or in any Scottish newspaper that I can find) of any burials having been disturbed during the construction.

Despite this, the local Moray historian H.B. Mackintosh wrote in 1924 that:

The road on the left at Cardow leads to Knockando House, below which, by the railway, was the chapel and burying-ground of Pulvrenan. When making the railway, a number of human bones was disinterred, and three symbol stones were transferred to Knockando churchyard for preservation. [my emphasis]

This is not only unsourced but also surely inaccurate: I can find no record of burials being disturbed by the railway, and the stones are supposed to have been moved long before its construction. Mackintosh is often cited as a credible source, but this seems to me to be embellishment for effect.

Which stones were actually removed from the site?

But all the same, some early medieval carved stones were removed from this site, so there must have been something here, surely?

Or maybe not.

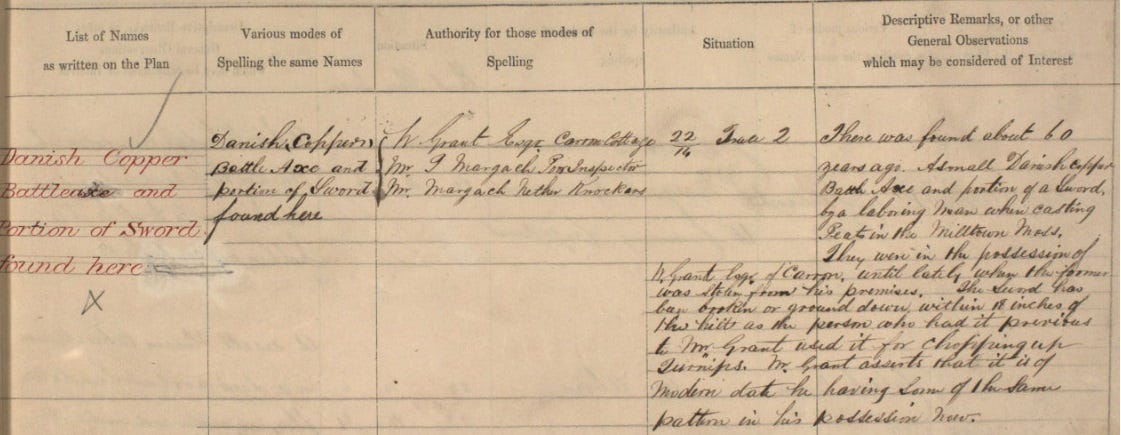

When the OS conducted their survey, they didn’t just collect information on place-names and spellings; they also collected information about antiquities discovered in each parish.

The Name-Book for Knockando is full of information about such finds: from the “urn and human bones” turned up by the plough at Cardow Farm, to the “Danish portion of sword” found in a peat moss and which one subsequent owner had apparently used for “cutting up turnips.”

And lo and behold, there is a record of a single ‘sculptured stone’ having been removed from the site next to Pool Veriner:

It reads:

Now Used as a Clan Stone and Claimed by a family of McDonald by whom it was brought from an Old Church land near the Railway a little below Knockando House & placed in the Parish Manse about fifty years ago, it now much obliterated & of unequal Surface is said to date from the ninth or tenth century [my emphasis]

This, surely, is a version of the story reported to Stuart, about the three stones being brought from “an old burial ground at Pulvrenan” to the parish church “about fifty years ago.” But in this version there’s only one stone; the land is a ‘Church land’ not a burial ground; and again it’s not named.

So which of the three stones is it? It’s not clear, but there is a hint. The description says the stone “is said to date from the ninth or tenth century.” This surely points to the ‘rune-carved’ stone, which Stuart’s expert contact Professor Stephens had said “may date from the ninth or tenth century.”

Had the people who testified to the OS also read Stuart’s book, published just a year or two earlier? I find it hard to see how the assertion that the stone dates from the ninth or tenth century could have come from anywhere else. And the witnesses here include two ministers: Rev. J. McDonald of Dallas, and Rev. T. Fraser of Archiestown, who might be expected to have had a copy of the book.

But what about the two Class I Pictish symbol stones that were also supposed to have come from the Pool Veriner site, and which are listed alongside the rune-carved stone in Stuart’s book? Strangely, there’s no mention of them anywhere in the Name Book. So did they even come from this site at all?

Conclusion: No evidence of an early church site

This has been a very complicated bit of research, and there are still things that don’t add up. But what I feel confident in concluding is that:

There is no physical evidence of an early Christian church or burial ground beside the Spey at Knockando, and no written evidence of such a site prior to 1867.

The site in question did not have a name until John Stuart, seemingly erroneously, called it ‘Pulvrenan’ in 1867.

Local sources disagree on whether all three stones were removed from the site, or just the ‘rune-carved’ stone, although they do agree that the removal took place around 1815.

The link to St Brendan was only made in 1973, by archaeologists reverse-engineering a Brendan dedication from the spurious name ‘Pulvrenan’.

Any link between this site and the lost medieval place ‘Abberbrandolthin Brenin’ or ‘Aberbrandely’ is misguided, as this place was almost certainly located south of the Spey.

So unless anyone can spot anything I’ve missed, I can only conclude that there was no early Christian site by the Spey below Knockando House, and certainly not one dedicated to St Brendan.

Postscript

What does intrigue me is that there’s no mention of the two Pictish symbol stones anywhere in the records prior to Volume II of Sculptured Stones of Scotland.

Even though they were apparently moved to the parish church around 1815, they aren’t included among the antiquities reported in the New Statistical Account (1835), they weren’t reported to Stuart for Vol I of SSS (1856), and they’re not mentioned in the OS Name Book (1868–1871).

It genuinely seems like the first anybody in Knockando knew about these stones was when they read about them in Volume II of Sculptured Stones of Scotland. In which case, who reported them to Stuart, and where did that person get the name ‘Pulvrenan’? But that’s quite enough of this for now!

References

All of the sources I’ve used for this blog have been linked in the text, apart from these, which aren’t available to read freely online:

Barnes, Michael P. ‘Towards an edition of the Scandinavian runic inscriptions in the British Isles: Some thoughts’ (1992)

Barrow, G.W.S. Badenoch and Strathspey 1130–1312, The Church (1989) – £30 paywall

Cowan, Ian B. The Parishes of Medieval Scotland (1967)

Mackintosh, H.B. Pilgrimages in Moray: A Guide to the County (1924)

Ross, A. The Province of Moray, c 1000–1230 (unpublished PhD thesis) (2003)

Rhind, W. Sketches of the Past and Present State of Moray (1839)

Watson, J. and Watson, W. Morayshire Described (1868)

Watson, W.J. The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (1926)

Many thanks to Adrián Maldonado and James Graham-Campbell for pointing out that this stone is no longer considered to be a genuine rune-stone, although the age and nature of the inscription are as yet unclear. See Michael P. Barnes, ‘Towards an edition of the Scandinavian runic inscriptions of the British Isles: Some thoughts’ (1992), page 38. (Also added to bibliography.)

Further correspondence with Professor Graham-Campbell has led me to his and Dr Colleen Batey’s 1998 book Vikings in Scotland: An Archaeological Survey, which mentions the rune-carved stone on page 105 thus: “A putative runic inscription on a stone from Knockando… has been shown by Aslak Liestøl to date from the eighteenth century!” I haven’t been able to track down a copy of Liestøl’s chapter discussing the stone, which is in the 1983 book The Northern and Western Isles in the Viking World edited by Alexander Fenton and Herman Pálsson.

UPDATE 28/12: Many thanks once again to James Graham-Campbell, who has located and sent me Aslak Liestøl’s opinion on the Knockando rune-stone, which is as follows:

“[This] inscription has for a long time been recognised as a genuine Viking relic. It was found on a stone in Knockando, Moray. I had some doubts about it because of its very irregular runes. In addition the place where it was found was – in my opinion – unlikely. An inscription on a stone, presumably a memorial stone, seems to point to a permanent settlement. But this was found in the fertile Strathspey … the place seemed an unlikely choice by a Scandinavian. It would probably have been very risky to venture into the heartlands of Moray in those times.

… when the stone was finally located, my doubts were confirmed and the markings on the stone turned out to be rather recent. Near the base of the stone there were some formerly unnoticed capital letters and a date 1714. The ‘runes’ seemed to be the remains of an ornament where the left half is flaked off (Fig. 71).

Aslak Liestøl (1984), ‘Runes’, in A. Fenton and H. Pálsson (eds), The Northern and Western Isles in the Viking World: Survival, Continuity and Change (John Donald; Edinburgh), 224-38.

I can't stop laughing at:

"However, some of Milne’s other interpretations suggest that he was a man who knew some Gaelic and wanted to show it off, rather than someone with a deep grasp of onomastics."

Lucky for him you weren't around back then to stick a pin in his balloon of self-importance, lol.

In case it's of any interest regarding pre-SSS references to Pulvrenan, Pont marks the Kirk of Knock Andich suggesting that it wasn't known as Pulvrenan at that time (at least to him) but that it was a known church site.

https://maps.nls.uk/pont/view/?id=pont06r#zoom=6&lat=1702&lon=2461&layers=BT