An early mention of Sueno’s Stone in the Historia Regum Britanniae?

In which I examine Alex Woolf’s idea that Sueno’s Stone makes a cameo appearance in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s twelfth-century History of the Kings of Britain.

If you’re new to this blog (hello!) I’m currently exploring possible early references to Sueno’s Stone—a huge ‘Pictish’ cross-slab near Forres in Moray—in medieval literature.

If you’re not new to this blog but you are fed up of me going on about Sueno’s Stone all the time, rest assured this is the last post for a little while on that topic.

I also apologise in advance that this blog is quite complicated. I wanted to see how well I could tackle the question with my current knowledge, but I have a feeling I’m trying to run before I can walk.

But anyway, here goes.

Tracking down the earliest surviving mention of Sueno’s Stone

One of the arguments against Sueno’s Stone having stood in the same spot for the past 1,200 years is that there’s no mention of it in any written text from before 1700.

Leslie Southwick, in a booklet on the stone written for Moray District Libraries in 1981, is pretty clear on the lack of early references:

It is probable that Sueno’s Stone lay buried for several centuries. This is suggested first by its condition which, had it stood in its exposed position continuously, would have suffered far more than it has from the wind-blown sand and rain. Secondly, there are no early records of the stone before the eighteenth century.

In 1993, David Sellar was content to confirm, referencing Southwick, that:

…it seems likely, both from its condition and from the lack of reference to it before the 18th century, that it must have lain buried for many centuries.

In a 1996 article, archaeologist Rod McCullagh, who had led an excavation around the stone in 1991, managed to push the documentary horizon back to the sixteenth century:

Only one document of any authority records the location of the stone prior to the 17th century. On the manuscript of Timothy Pont's Mapp of Murray (c 1590) two stones have been depicted lying north of Forres.

(NB The possibility of there having been two stones on the site is one I discussed here.)

And for most commentators on the stone, 1590 is where the trail goes cold. If it has stood in the same spot since the ninth or tenth century, it seems nobody mentioned it for the first 600 or so years of its existence—at least not in any text that survives today.

An early mention from the 1130s?

But at the end of a 2010 article, historian Alex Woolf floated the “very speculative” possibility that the stone appears briefly in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s twelfth-century Historia Regum Britanniae (HRB for short), or History of the Kings of Britain.

Woolf only raises this as a parting thought in his article, and nobody seems to have followed up on it since. So for this blog I’m going to try to see how well it checks out.

About Geoffrey of Monmouth and Historia Regum Britanniae

First, some context. Geoffrey, a British or Welsh cleric living and teaching in Oxford, completed his History sometime between 1130 and 1138. It claims to recount the history of the island of Britain from its mythical foundation by one Brutus, great-grandson of Aeneas of Troy, to the death of Cadwallader, a historical king of Gwynedd who died of the plague in 682 AD.

The book is almost wholly fantastical and entirely unreliable as straightforward history. It has however always been wildly popular as a source of the legends of Merlin and King Arthur (among others), which inspired later retellings by Chrétien de Troyes, Thomas Malory and others.

The possible reference to Sueno’s Stone isn’t in the Arthurian bit, but in a short section about Marius—a mythical king of Britain who, according to HRB, ruled around the time of the Roman emperor Vespasian in the late first century AD.

The story of Marius takes up less than a page of the Penguin Classics edition of HRB, so it’s worth setting out in (almost) full before diving in.

The story of Marius, a mythical king of Britain

First, we hear of Marius’s accession on his father Arvirargus’s death:

Marius, the son of Arvirargus, succeeded him in the kingship. He was a man of great prudence and wisdom.

Next we hear of an invasion of the north of Britain—a region Geoffrey calls ‘Albany,’ an anglicisation of the Gaelic Alba, which is how Gaelic-speakers in Geoffrey’s time referred to Scotland.

A little later on in his reign a certain king of the Picts called Sodric came from Scythia with a large fleet and landed in the northern part of Britain which is called Albany. He began to ravage Marius’s lands. Marius therefore collected his men together and marched to meet Sodric.

A war then ensues between the ‘Pictish’ invader Sodric and the ‘British’ king Marius:

[Marius] fought a number of battles against [Sodric] and finally killed him and won a great victory.

Then comes the bit that Woolf suggested refers to Sueno’s Stone:

In token of his triumph Marius set up a stone in the district, which was afterwards called Wistmaria after him. The inscription carved on it records his memory down to this very day.

That’s not the end, though, because we then hear of Marius’s generosity towards Sodric’s defeated invasion force:

Once Sodric was killed and the people who had come with him were beaten, Marius gave them the part of Albany that is called Caithness to live in. The land had been desert and untilled for many a long day, for no one lived there.

This is followed by a story that anyone familiar with the origin legend of the Picts will likely recognise:

Since they had no wives, the Picts asked the Britons for their daughters and kinswomen; but the Britons refused to marry off their womenfolk to such manner of men. Having suffered this rebuff, the Picts crossed over to Ireland and married women from that country. Children were born to them and in this way the Picts increased their numbers.

Geoffrey ends his story with the sentence that originally attracted Alex Woolf’s attention, since it presents a surprisingly accurate view of the ancestry of the Scots:

This is enough about [the Picts], for it is not my purpose to describe Pictish history, nor, indeed, that of the Scots, who trace their descent from them, and from the Irish, too.

Echoes of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History

So what sense can we make of this story of mythical king Marius—and more specifically, of the stone he had set up in a district called Wistmaria to commemorate his triumph against an invading force?

The first and easiest thing to say is that the part of the story about the Picts seeking wives from the Irish has been adapted from Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, which is known to be one of Geoffrey’s sources.

Writing in 731 AD, Bede describes how the Picts were the second race of people to arrive on the island of Britain after the Britons. In Bede’s telling, the Picts set sail from ‘Scythia’ (by which he meant Scandinavia) and landed first in Ireland. However, they were told that Ireland was full (the age-old fate of migrants arriving in small boats) and that they should seek land in Britain instead.

This they did, settling “in the north of the island, since the Britons were in possession of the south.” But before they left Ireland, they asked the Irish for wives as they’d brought no women with them. The Irish granted their wish, on the condition that “when any dispute arose” they should choose a royal successor from the female line rather than the male.

While Bede’s intention was probably to provide a ‘historical’ explanation for Pictish royal succession practices (a topic on which much ink has been spilled), Geoffrey is writing over two centuries after the Picts ‘disappeared’ (another topic on which much ink has been spilled), so this aspect isn’t important to him and he leaves it out. His reason for including the ‘Irish wives’ story is no doubt to lend credibility to his work by aligning it with Bede’s very well-known history.

In any case, Bede doesn’t mention a king Marius of the Britons, a king Sodric of the Picts, the raising of a commemorative stone, or a district in Scotland called Wistmaria. So where might Geoffrey’s story of Marius’s battles with Sodric, and the stone recording Marius’s eventual triumph, come from?

Geoffrey’s History: editions and sources

Now, there are acres of scholarship about Geoffrey of Monmouth, his writing and his sources, and I must confess I’ve not read very much of it. However, I have read enough to know the following:

There is no definitive ‘original’ version of the Historia Regum Britanniae. Instead there are over 200 different manuscript versions of it, in various languages (Latin, English, Welsh, Old Norse), all with variations between them, as is usual for hand-copied medieval manuscripts.

In 1929 Acton Griscom produced the (then) most accurate Latin edition, basing it mainly on a manuscript version kept in the Cambridge University Library, with footnotes indicating key variations in three other manuscript versions (two in Latin, one in Welsh).

In 1966 Lewis Thorpe translated Griscom’s edition into English; this is the widely-available Penguin Classics edition that I’ve used for the quotations above.

A new English translation was made in 2007 by Neil Wright for Boydell and Brewer. This ‘academic’ edition is based on a synthesis of 17 manuscript versions of HRB considered by editor Michael Reeve to be the most authentic. This is the version Alex Woolf used for his article, and it has important differences from the Penguin Classics version. For example, it gives the name of the ‘Pictish’ leader that Marius fought as ‘Rodric,’ rather than ‘Sodric’.

Geoffrey’s sources are usually considered to be a mix of earlier histories of Britain that we can still read today (Nennius’s Historia Brittonum, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, Gildas’s De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae) along with some Roman sources, an amount of folklore, and stories passed on orally (or perhaps in a now-lost written form) by people in his social and intellectual circle—particularly Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford.

Debate still rages over how much Geoffrey drew from his sources, and how much he invented to join the dots and tell a satisfyingly continuous story. But one thing is certain: the story of Marius’s battles with ‘Sodric’ and the victory stone he had set up in the eponymous district of Wistmaria doesn’t come from any written source known to us today.

Is Marius’s stone itself the source of the story?

But maybe the source for this particular story wasn’t a document. HRB describes the stone thus:

The inscription carved on it records [Marius’s] memory down to this very day.

This suggests that the stone, apparently still extant in the twelfth century and bearing an intelligible “inscription,” could itself be the source of the story. The Geoffrey scholar J.S.P. Tatlock certainly thought Geoffrey had a real monument in mind, saying:

That Geoffrey knew of some such inscription then visible is hard to doubt.

On that basis, Sueno’s Stone could well be a candidate. It’s a remarkable monument even today due to its great 6.5m height, so it must surely have attracted attention in the twelfth century too. Although it doesn’t have an inscription as such, it’s usually thought to commemorate a military victory, and its battle scenes are complex enough to be considered a narrative source in their own right.

However, there’s at least one other early medieval carved stone in Scotland that depicts warfare—the Battle Stone at Aberlemno—so this on its own isn’t enough to securely identify Marius’s stone with Sueno’s Stone.

Locating Wistmaria: Westmorland, Moray, or somewhere else?

It would be possible to make a stronger identification with Sueno’s Stone if we knew where Geoffrey meant by Wistmaria, since this is where he claims Marius’s victory stone still stands.

Scholars usually think it’s meant to be Westmorland in Cumbria. This led Tatlock to suggest that Geoffrey was thinking of a Roman altar now in Carlisle Castle, which was noted in 1125 as bearing the inscription MARII VICTORIAE (now thought to have been MARTI VICTORIAE; Mars and Victory).

But Woolf argues that Geoffrey actually meant Wistmaria to mean Moray in Scotland, where Sueno’s Stone is. As evidence, he points out that the rest of the Sodric/Rodric story takes place in Scotland:

Westmorland, in Geoffrey’s time probably still understood simply as the territory dependent upon Appleby, north of the Lake District massif, does not seem particularly close to Caithness or the northern parts of Scotland identified as the location of Rodric’s raid.

He also notes that HRB elsewhere uses a different place-name that’s closer in spelling to Westmorland:

[The name] Westmarialanda appears elsewhere in the text and may have been intended to represent a different location to Wistmaria.

Much as I like these points, they are a bit debatable. The text doesn’t say that Sodric/Rodric lands in the northern part of Scotland but in the “north of Britain,” although Geoffrey does say that this northern part of Britain is called Albany, meaning Scotland.

However, it’s not clear that he means the northern part of Scotland particularly, and as Westmorland had once been part of the early medieval kingdom of Strathclyde, the last remnants of which had recently been absorbed into Scotland at the time Geoffrey wrote HRB, it could still be the place meant.

On Woolf’s second point, it is true that Westmarialanda also appears once in the text, on page 33 of the Penguin Classics edition. But Geoffrey implies that it too is in ‘Albany,’ so it may just be a variant spelling of Wistmaria. And elsewhere, he uses Mureif to mean Moray, further undermining the Wistmaria-as-Moray argument.

Rodric: An echo of a real, tenth-century Ruaidrí of Moray?

However, Woolf strengthens his identification of Wistmaria with Moray by noting the similarity of the name ‘Rodric’ to that of Ruaidrí, the grandfather of Macbeth and founder of the dynasty that ruled Moray in the late tenth and eleventh centuries.

Unlike Sodric/Rodric, though, this historical Ruaidrí wasn’t a Pict but a Gael: a descendant of immigrants from Ireland or Dál Riata (Argyll). His family were rulers of Moray, not newly-arrived raiders from overseas. And he lived in the tenth century, not during the Roman occupation of Britain.

However, in Geoffrey’s time Moray had a reputation for causing trouble for Scottish kings—notably David I, who held the throne of Scotland at the time Geoffrey was writing—by producing rival claimants to the throne who had to be (violently) suppressed.

So the identification of Wistmaria with Moray, and Marius as a king who had to put down unrest in that region, does at least chime with contemporary twelfth-century Scottish politics. But other than that, the argument for identifying Geoffrey’s possibly-fictional district of Wistmaria with the medieval province of Moray seems quite tenuous.

Wistmaria and the ‘Westschyre of Murray’

If we do believe that Wistmaria is meant to be Moray, I have an ultra-tentative suggestion for why Geoffrey says it was named Wistmaria after Marius, rather than just Maria or indeed Mureif.

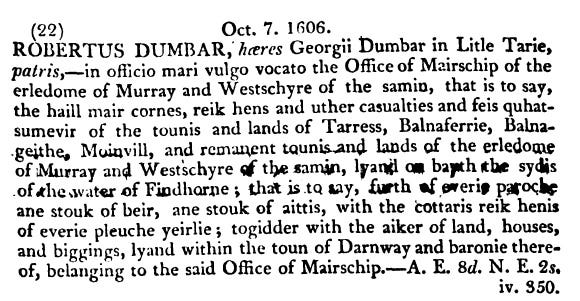

According to a seventeenth-century retour (legal confirmation of inheritances), on 7 October 1606, one Robertus Dumbar of Little Tearie in Moray inherited from his father George Dumbar:

the Office of Mairschip of the erledome [earldom] of Murray and Westschyre of the samin [same]

So far, this is the only reference I’ve come across to a ‘Westshire of Moray,’ and it’s from more than 400 years after Geoffrey was writing. But the farm townships listed as owing duties to the mair of “the earldom of Moray and Westshire of the same” do include the one on whose land Sueno’s Stone stands: Tarras (Tarress) in the parish of Rafford, just east of Forres:

…the tounis and lands of Tarress, Balnaferrie, Balnageithe, Moinvill, and remanent tounis and lands of the erledome of Murray and Westschyre of the samin, lyand on bayth the sydis of the water of Findhorn.

So if the land on which Sueno’s Stone stands was once in a ‘Westshire of Moray,’ that might strengthen the link with Wistmaria. But that would imply that Geoffrey knew that Sueno’s Stone was located in the Westshire of Moray, and as far as I know there’s no evidence he ever visited Scotland.

A twelfth-century legend based on Sueno’s Stone?

But perhaps Geoffrey heard of the stone by some other means. There is a tiny hint that a legend inspired by Sueno’s Stone may have been in circulation in the twelfth century.

Towards the end of my last blog, I floated the idea that the carvings on Sueno’s Stone were the inspiration for another work of high-medieval literature: the story in Chapter 5 of the Icelandic Orkneyinga saga about a battle between Máel Brigte, mormaer of Moray, and Sigurd the Mighty, first Norse earl of Orkney.

The story of Máel Brigte and Sigurd and the story of Marius and Sodric/Rodric have some interesting similarities, suggesting that they may be garbled versions of a common source.

For a start, they’re both set in Scotland, and both involve a battle between a native ruler and a recent arrival from Scandinavia, fought on the native ruler’s territory.

Both stories also end in the far north of Scotland, with Sigurd being buried in a mound at Ekkialsbakki in Sutherland, and Sodric’s followers being granted the region of Caithness to live in. And if we take ‘Sodric’ rather than ‘Rodric’ to be the correct name of HRB’s invader, the protagonists’ names start with the same letters in both stories: Marius/Máel Brigte and Sodric/Sigurd.

Both stories are also oddly self-contained, as if all that’s known about Sodric and Marius, or Sigurd and Máel Brigte, is that one of them invaded the other’s territory, that this happened in Scotland, and that a battle or battles were fought between them until one or both of them were dead.

In other words, both stories feel like the type of legend that could have been inspired by a carved stone, rather than an extended narrative source.

So was there a legend going around in the twelfth century, based on Sueno’s Stone, which found its way into both HRB and Orkneyinga saga? And if so, how might it have reached their respective authors?

A mutual connection through David I of Scotland?

Well, it does seem that both authors were within a couple of degrees of separation from David I of Scotland (r. 1124–1153).

Little is known of Geoffrey’s social circle, but it seems to have been elevated: his HRB is dedicated to Robert of Gloucester, one of Empress Matilda’s closest allies during her attempt to claim the throne of England in 1139–1141. And another of Matilda’s closest allies was David I, her uncle, with whom she’d spent time at court during her childhood.

Some 18 years her senior, David was always very fond of his niece. Is it possible to imagine that he might have told the young Matilda a story based on the carvings on a stone in the north of his future kingdom of Scotland, and that this story was passed by Matilda to Robert and from Robert to Geoffrey (who was, after all, surely seeking source material for his History)?

What’s interesting is that in HRB, King Marius ends up granting Sodric’s followers the land of Caithness to live in. Is it a coincidence that David I was very keen to reclaim Scottish lordship over Caithness, then under the rule of the Norse earls of Orkney? In that case, Geoffrey’s story may have been intended to flatter David by portraying a king with authority to grant land in Caithness.

How did the legend get included in Orkneyinga saga?

What about Orkneyinga saga? Its anonymous author was writing at the turn of the thirteenth century, long after David’s death in 1153, so they wouldn’t have been connected to him personally.

But Orkneyinga saga, like HRB, was compiled from a mixture of older sagas, folk-tales and oral tradition. And the part that deals with Rögnvald Kali Kolsson, earl of Orkney from 1136 to 1158, appears to draw directly in places from the testimony of Sveinn Asleifsson, an old-school viking and political ‘fixer’ who claimed to have the ear of David I and at times seems to be acting on David’s orders.

In the saga Sveinn travels through Moray twice on his way to Atholl, and it’s not too much of a stretch to imagine him admiring Sueno’s Stone in passing, and discussing its battle scenes with David or with people in David’s circle. (To me it doesn’t seem entirely beyond the realms of possibility that the stone is actually named after Sveinn Asleifsson, but I’d best not get into that.)

In this scenario, Sveinn would not only have provided material for Orkneyinga saga from his own time, but supplied the legend of the battle of Máel Brigte and Sigurd as well.

Hold on a minute, though…

However, this doesn’t explain how the Máel Brigte and Sigurd of the saga mutated into the Marius and Sodric of HRB (or vice versa), especially if both stories came from the same source in the 1130s.

And if the two stories are both based on a legend circulating in the twelfth century, it’s odd that the same legend doesn’t appear in any of the later medieval histories of Scotland, like John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, or Andrew of Wyntoun’s Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland.

So I may just be seeing similarities and connections where there aren’t any.

[UPDATE 04/10: Well, on re-reading Woolf’s paper I see that a version of the story does appear in Fordun’s Chronicle, so perhaps I’d better actually check that out.]

So is Sueno’s Stone the stone mentioned in Historia Regum Britanniae?

After all of this research, which has taken about a month, all I think I can conclude is that:

Sueno’s Stone is a good candidate for the inscribed stone mentioned in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, but it doesn’t seem possible to prove it definitively.

The district of Wistmaria, where Geoffrey says the stone stands, may be related to the ‘Westshire of Moray’ mentioned in a legal document of 1606, which included the land of Tarras on which Sueno’s Stone stands.

(I would love to hear from any Moray historians on this, if only to rule it out. Could this Westshire also have been in existence in the twelfth century?)

The same basic legend may appear in a different form in Chapter 5 of Orkneyinga saga. Or the parallels between the two stories may just be coincidental.

Geoffrey may have heard of a legend based on the stone from someone in the circle of David I, with which he seems to have been connected. The author of Orkneyinga saga also seems to have had access to oral or written material produced by someone—Sveinn Asleifsson—who was close to David I.

If the two stories are based on the same legend, someone in David’s circle may have been the source in both cases, since there’s no evidence that either author ever went to Moray or saw the stone themselves.

Very many thanks to anyone who’s stuck with this very complicated investigation to the end! As ever, I’d be very happy to hear anyone’s thoughts.

References

Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, translated by Leo Sherley-Price (1955)

Crawford, Barbara. The Northern Earldoms: Orkney and Caithness from AD 870 to 1470 (2013)

Geoffrey of Monmouth. The History of the Kings of Britain, translated by Neil Wright (2007)

Geoffrey of Monmouth. The History of the Kings of Britain, translated by Lewis Thorpe (1978)

Hanley, Catherine. Matilda: Empress, Queen, Warrior (2019)

Inquisitionum Ad Capellam Domini Regis Retornatarum, Quae in Publicis Archivis Scotiae Adhuc Servantur, Abbreviatio, Volume 1 (1811)

McCullagh, Rod. Excavations at Sueno’s Stone, Forres, Moray (1995)

Oram, Richard. Domination and Lordship: Scotland 1070 to 1230 (2011)

Pálsson, Herman and Paul Edwards (trs). Orkneyinga saga: The History of the Earls of Orkney. Penguin Classics (1978)

Sellar, W.D.H. Sueno’s Stone and Its Interpreters (1993)

Southwick, Leslie. The So-Called Sueno’s Stone at Forres (1981)

Tatlock, J.S.P. The Legendary History of Britain: Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae and Its Early Vernacular Versions (1974)

Tatlock, J.S.P. Geoffrey of Monmouth’s motives for writing his Historia (1938)

Taylor, Alexander Burt. A study of the Orkneyinga saga with a new translation (1935)

Woolf, Alex. Geoffrey of Monmouth and the Picts (2010)

Very interesting ideas - thanks all. Dr John Barrett in Forres did his PhD on the early mediaeval routes into and through Moray. His research might detail here. I was looking at a more hare brained (!) idea likely the product of an over lurid imagination, following the Northern Pict projects recent excavations of Burghead Palace sites and their thinking re Fortriu. I wondered whether the pair of suenos stones depicted in the early map image were a gateway within a protective 'necklace' of boundary markers delineating a vaguely circular boundary line with its centre at Burghead, perhaps defining a route from Fortriu Palace south west towards the route from the laich of Moray to the upper highlands, perhaps on the approximate established line from Forres to Aviemore.

I was playing with the fanciful notion of might that have been Bridei's triumphant AD 685 return route from his success at Nechtansmere (over which a small group of us are exploring further fanciful notions about a possible battle site in the 'narrow pass though inaccessible mountains' of the Gaick pass), and wondering if these grandest of stones, carved a few generations later, might have marked that event that gave the Pictish nation its 'modern' political foundation. We were exploring whether the battle sequencing and the beheading depictions on the rear (or perhaps front?) might fit the Bede and later Annals' descriptions of the ambush and executions of Ecgfrith's warband, the elimination of Northumbrian hegemony after the two rivers battle humiliation, and the re-establishing of the independence of their nation?

Like I say, lurid imaginings! Thanks for all your fascinating work here and for everyone's well considered contributions. We have such an intriguing history.

Hi Fiona, great spot of Westshire of Moray and particularly the explicit link to Tarras, but….

Whilst these locations are very much the west side of 17th C Moray, with the Findhorn as the boundary, early medieval Moray seems to have stretched much further west, at least as far as Inverness and the boundaries of Ross.

That said, this unusual reference may be a fossil of an earlier land division of West Moray that perhaps did once stretch from, say, Forres to Inverness - which would then put the stone, once again, on a boundary.

Certainly more food for thought