Does Sueno’s Stone record the battle of Sigurd the Powerful and Máel Brigte ‘Tooth’?

In which I examine W.F. Skene’s suggestion that Sueno’s Stone records a legendary ninth-century battle.

In my last blog I tried to work out if a ninth-century Norse earl of Orkney, Sigurd the Powerful, had ever conquered land in Moray, as Orkneyinga saga says he did.

My conclusion was “probably not,” as there isn’t enough independent evidence to say for sure whether Sigurd even was earl of Orkney in the ninth century, and the archaeological and place-name evidence for Norse conquest and settlement in Moray is minimal (but not completely non-existent).

Instead, I floated the idea that Sigurd’s mythical conquest of Moray may be the result of the saga author’s misunderstanding of the place-name Ekkialsbakki. It’s fairly certain that this name refers to the bank of the River Oykel and the Dornoch Firth—the border of Sutherland and Ross. But the saga author always seems to place it much further south, somewhere on the Moray Firth coast.

Another Norse saga, Heimskringla, says that Sigurd and his ally Thorstein conquered “Caithness and Sutherland, all the way to Ekkialsbakki,” and I suggested that the Orkneyinga saga author (who lived in Iceland) may have mistakenly thought this meant they also conquered Ross and part of Moray.

A connection between Orkneyinga saga and Sueno’s Stone?

The reason I’m interested in this is because the story of Sigurd is related to my MA research on Sueno’s Stone—a 6.5m carved cross-slab near Forres in Moray.

In a long footnote on pp 337–338 of his 1873 book Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban, the Scottish historian William Forbes Skene proposed that Sueno’s Stone records the battle narrated in Chapter 5 of Orkneyinga saga, between Sigurd and an earl of Moray called Máel Brigte ‘Tooth’.

In this blog I want to look at whether the carvings on the stone really do match the story of this battle, and if so, what (if any) relationship these two narratives might have.

The battle in Orkneyinga saga

First let’s recap the story of the battle, which, by Orkneyinga saga’s chronology, takes place sometime in the last quarter of the ninth century. It comes straight after the story about Sigurd’s conquests in Moray, which is narrated as follows:

Earl Sigurd became a great ruler. He joined forces with Thorstein the Red, the son of Olaf the White and Aud the Deep-Minded, and together they conquered the whole of Caithness and a large part of Argyll, Moray and Ross. Earl Sigurd had a stronghold built in the south of Moray.

The narrative then shifts to the battle:

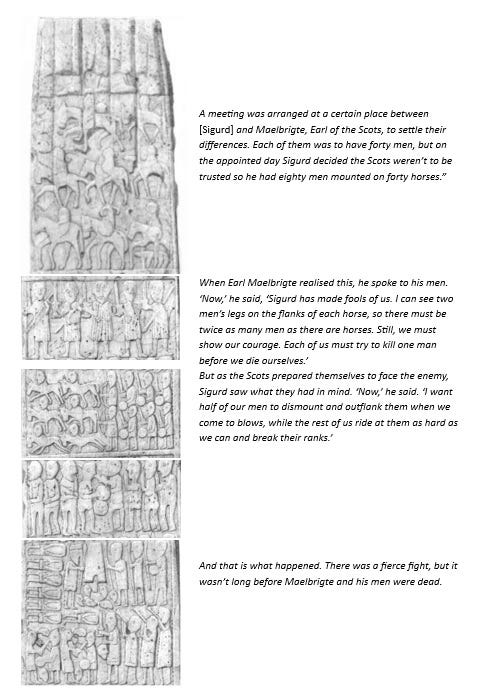

A meeting was arranged at a certain place between [Sigurd] and Maelbrigte, Earl of the Scots, to settle their differences. Each of them was to have forty men, but on the appointed day Sigurd decided the Scots weren’t to be trusted so he had eighty men mounted on forty horses.

It’s noticeable that the battle is arranged at a “certain place.” As Orkneyinga saga usually names real places, this vagueness lends the story a fuzzy, urban myth-like quality. The location is presumably somewhere on the Scottish mainland, though, as Sigurd and his men are arriving on horseback rather than by sea from Orkney.

In any case, Máel Brigte soon catches on to what Sigurd is up to:

When Earl Maelbrigte realised this, he spoke to his men. ‘Now,’ he said, ‘Sigurd has made fools of us. I can see two men’s legs on the flanks of each horse, so there must be twice as many men as there are horses. Still, we must show our courage. Each of us must try to kill one man before we die ourselves.’

Sigurd in turn catches on to Máel Brigte’s plan:

But as the Scots prepared themselves to face the enemy, Sigurd saw what they had in mind. ‘Now,’ he said. ‘I want half of our men to dismount and outflank them when we come to blows, while the rest of us ride at them as hard as we can and break their ranks.’

Then follows the battle itself:

And that is what happened. There was a fierce fight, but it wasn’t long before Maelbrigte and his men were dead. Sigurd had their heads strapped to the victors’ saddles to make a show of his triumph, and with that they began riding back home, flushed with their success.

But Máel Brigte has the last laugh:

On the way, as Sigurd went to spur his horse, he struck his calf against a tooth sticking out of Maelbrigte’s mouth and it gave him a scratch. The wound began to swell and ache, and it was this that led to the death of Sigurd the Powerful. He lies buried in a mound at Ekkialsbakki.

Ekkialsbakki: a place near Forres?

It’s the mention of the mound at Ekkialsbakki that put Skene in mind of Sueno’s Stone. Like others, he had noticed that every time the saga author uses this place-name, it seems to indicate somewhere on the southern shore of the Moray Firth, rather than the Oykel or Dornoch Firth.

He notices especially that in Chapter 78 of the saga, Ekkialsbakki is on the route Svein Asleifsson takes from Orkney to Atholl. This leads him to propose a location on the River Findhorn:

…the passage in chapter [78], where Swein Asleif’s son goes to Moray, and thence by Ekkialsbakki to Atholl, points to the Findhorn, which is remarkable for a high bank, has an estuary which ships could enter, and would be the natural route to Atholl.

Skene here accurately describes the gorge of the Findhorn as it makes its way down through Glenferness and the Darnaway Forest towards Forres, and Findhorn Bay, the bag-shaped estuary of the river just to the north of Forres. And this leads to his Sueno’s Stone idea:

The battle may have been fought near Forres, and the sculptured pillar known by the name of Sweno’s Stone a record of it.

He then proceeds to describe the scenes on the stone’s two main faces, in an effort to persuade his reader of their similarity to the story of Sigurd and Máel Brigte.

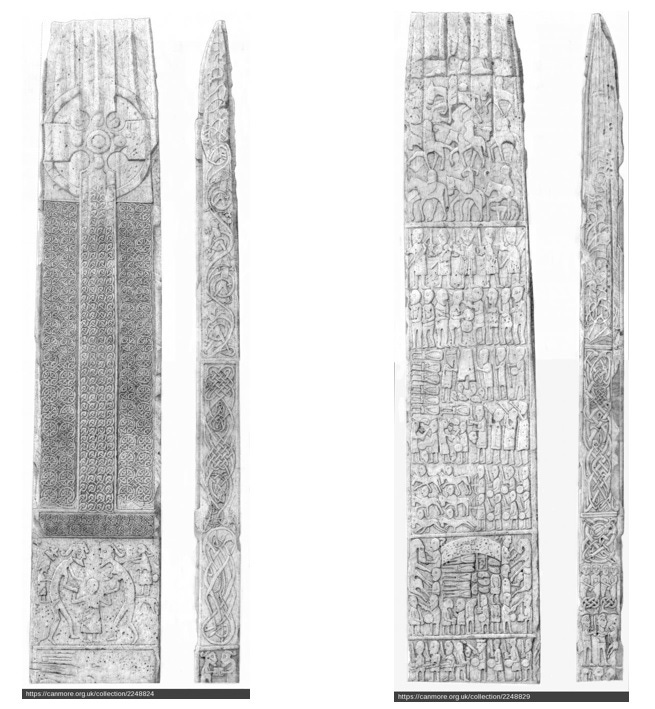

Let’s see how persuasive his argument actually is, using the fantastic recent drawings of the stone by John Borland for Historic Environment Scotland (available on CANMORE here and here and reproduced with permission).

The meeting to arrange the battle

First, Skene says:

On one side are two figures engaged in apparently an amicable meeting, and above a cross with the usual network ornamentation.

This refers to the curious panel below the cross on the west face of the stone, which is now so eroded it’s hard to make anything out. But certainly, two figures are facing each other, supporting Skene’s interpretation of a meeting (presumably of envoys, rather than Sigurd and Máel Brigte themselves):

A meeting was arranged between Sigurd and Maelbrigte, Earl of the Scots, to settle their differences.

However, the two main figures are bending over an almost-fully-eroded central figure, which Skene doesn’t mention, and which undermines his idea that they’re meeting to arrange a battle. So I’d give this 5/10 for similarity to the saga story.

The battle itself

As the battle commences, Skene’s interpretation shifts to the east face of the stone. He reads the stone (although not its narrative) from bottom to top, starting with the lowest panel:

On the other side we have below a representation which it is difficult to make out, but it seems to show a number of persons as if engaged in council, the background probably representing the walls of some hall or fortification.

This panel is only half of the whole panel, as the lower half is covered by the stone collar that holds the stone in place. But as John Borland’s drawing shows, it features warriors in close combat with swords and shields, including a ‘leader’ figure who seems to be wearing something on his head, and who is decapitating a warrior from the opposing side.

It definitely doesn’t show “a number of persons as if engaged in council,” so I’m afraid Skene gets 0/10 for this one, although the panel itself does support the general warlike tenor of the saga story.

A party of horsemen at full gallop

Skene then skips the next panel up, and moves to the central panel of the stone, where he sees:

…a party of horsemen at full gallop, followed by foot-soldiers with bows and arrows.

This tallies well with the stone, other than that six of the eight foot-soldiers have swords and shields rather than bows and arrows. It also fits well with Sigurd’s instruction to his warband in the saga:

I want half of our men to dismount and outflank them when we come to blows, while the rest of us ride at them as hard as we can and break their ranks.

So I’m giving this scene a solid 10/10 for similarity with the saga story.

A leader with a head hanging at his girdle

Next comes the scene that I sense Skene is most confident about:

Above that we have a leader having a head hanging at his girdle, followed by three trumpeters sounding for victory, and surrounded by decapitated bodies and human heads.

The figure with the “head hanging at his girdle” is central to the action, supporting the interpretation that he is the leader, and thus, in Skene’s view, Sigurd. And he is indeed accompanied by three trumpeters, who seem to be proclaiming the victory.

However, Skene loses points for not mentioning the conical object in the centre, beneath which the six severed heads are arranged and which is being approached, menaced or guarded by four figures.

Despite that, I’d say we have a good 7/10 for similarity to the saga, which relates:

There was a fierce fight, but it wasn’t long before Maelbrigte and his men were dead.

Some more similarities (or not)

Probably thinking his footnote is getting out of hand, Skene now telescopes the rest of the stone into one quick description:

Above that we have a representation of a party seizing a figure in Scottish dress; and below it a party, in which in the centre is a figure in the act of cutting off the head of another, and above all a leader riding on horseback, followed by seven others.

Here he jumps about, identifying first

…a representation of a party seizing a figure in Scottish dress.

I take this to be the row of five figures in which the ‘leader’ seems to be wearing a kilt (although a kilt is anachronistic for the ninth century and the garment must surely be a hauberk or gambeson of some kind).

By picking out the ‘Scottish dress’ Skene must see this as a depiction of the Gaelic earl Máel Brigte being seized by Sigurd’s Norsemen. However, I don’t personally think the carving supports the idea that the central figure is being apprehended—to me he looks like a leader flanked by four members of his warband, all with swords raised in a display of strength or readiness for battle.

So I’m giving Skene 4/10 for interpretation, but the scene itself actually fits well with the part of the saga story where Máel Brigte issues instructions to his men:

When Earl Maelbrigte realised this, he spoke to his men. ‘Now,’ he said, ‘Sigurd has made fools of us. I can see two men’s legs on the flanks of each horse, so there must be twice as many men as there are horses. Still, we must show our courage. Each of us must try to kill one man before we die ourselves.’

So 10/10 for the stone here.

A figure cutting off the head of another

Skene then moves down to the next scene where sees

…a figure in the act of cutting off the head of another.

And that’s exactly what’s happening on this row—in fact it’s a very close echo of the bottom panel of the stone, except that the ‘leader’ in this one is not wearing anything on his head, and his opponent still has his head (but not for much longer). So 10/10 for similarity to the saga.

A leader on horseback

Lastly, Skene looks to the top of the stone, where he sees:

…a leader riding on horseback, followed by seven others.

This is the most weathered part of the stone, and the very top is virtually impossible to make out. But Skene is correct in that there are people on horseback here, and John Borland’s drawing gives a sense of one horseman at the top with eight others (and a dog) below, ranged in 2-3-3 formation.

This top panel does indeed seem to show one of the warring sides riding on horseback to the battle, as Sigurd’s side does in the saga:

Each of them was to have forty men, but on the appointed day Sigurd decided the Scots weren’t to be trusted so he had eighty men mounted on forty horses.

There’s no sense on the stone of there being two people to each horse; a crucial aspect of the saga story. But the carving is very weathered so it’s hard to know how it looked before erosion set in. If I give Skene the benefit of the doubt, this panel could score a good 8/10.

Does the stone really record the battle of Sigurd and Máel Brigte?

It’s quite easy to see why Skene thought the stone depicted the saga battle, and that the battle took place in the Forres area. But how credible is the idea really?

To my mind, not very, for these reasons:

Outside of the sagas, there’s no independent evidence that a Sigurd the Powerful, earl of Orkney, and a Máel Brigte, earl of the Scots, ever existed in the ninth century.

As a Norse earl of Orkney, it seems highly unlikely that Sigurd would arrive at a battle in Moray on horseback. If he came to Forres at all, he would have sailed there.

The stone omits two crucial elements: 1) that Sigurd and his men each tied the head of a defeated warrior to their saddle, with Sigurd tying the head of Máel Brigte to his, and 2) that Sigurd was scratched by Máel Brigte’s tooth on the way home, leading to his death.

The stone is erected on the ostensible loser (Máel Brigte)’s territory, but seems to celebrate a victory.

The cross signals that it was a Christian victory, but Sigurd was a pagan.

So although there are strong similarities, it doesn’t seem credible that Sueno’s Stone actually records the battle narrated in the saga—or that the battle (if indeed it ever happened) took place on the spot where the stone stands.

But all the same, I wonder if there is some connection—and this is where you’ll have to indulge an idea that I’m testing out.

More similarities between the stone and the saga

There are a few similarities between the saga story and the stone that I find interesting, including some that Skene didn’t mention.

One is the mathematical aspect of the story. In the saga, Sigurd’s and Máel Brigte’s sides are meant to be evenly matched at 40 men each, but Sigurd brings 80 men on 40 horses. In an exhaustive analysis of the stone’s composition, Dr Anthony Jackson noted in his 1984 book The Symbol Stones of Scotland that its two warring sides are also unevenly matched, with one side having 42 warriors and the other 56.1

Another is that, as we’ve seen, some of the scenes on the stone can be mapped to some of the scenes of the saga, although not in the same order. Here are the panels again that I think could be considered as mirroring the saga, with the saga text alongside.

However, after this, the narratives diverge. The stone shows yet more fighting and more piled-up heads and bodies. In the saga, Sigurd’s men tie the heads of the defeated warriors to their saddles and start to ride back home. Sigurd is scratched by the tooth on the way, eventually dies of blood poisoning, and is buried in a mound at Ekkialsbakki.

Two man-made structures in the saga and on the stone

But perhaps there are similarities even here. It’s notable that the saga story is bookended by two man-made structures: a fort that Sigurd has had built in Moray, which may be the catalyst for the battle with the local earl Máel Brigte, and the mound he is buried in at the end of the story.

Similarly, there are two apparently man-made structures on the stone, each given a prominent role. One is the conical object in the left-hand panel below, which is usually interpreted as a broch or fort of some kind (although others have seen it as a bell or a bloomery furnace).

The other is in a large panel near the base of the stone which Skene didn’t comment on, perhaps because he didn’t feel it supported his argument. This curved object is usually interpreted as a canopy or tent, although Professor Archie Duncan saw it as a bridge, and John Borland has suggested a hogback stone.

Looking more closely at this object, we can see that bodies and heads lie underneath it, with one head picked out in a frame. To either side, human figures can be seen interacting in some way with what look like a pair of horses.2

I wonder if, to a medieval imagination, this ‘canopy’ or ‘tent’ might be interpreted as a burial mound: one with multiple people interred in it, a suggestion of horse sacrifice—a known element of some elite early medieval Scandinavian warrior burials—and a head that is somehow ‘special’.

Was Sueno’s Stone a source for Orkneyinga saga?

What I’m suggesting, I suppose, is that Sueno’s Stone, rather than recording or commemorating the battle described in the saga, could actually be a source of the story narrated in the saga.

In this scenario, the stone could have inspired a story about a battle in Moray involving a fort, between one side on horseback and the other on foot, featuring many decapitations, ending with a burial mound, and having some association with a special head. Other folk-tale elements—the ‘two people to one horse’ trick, the tying of heads to saddles, the ‘avenging head’—could have filled the gaps.

What makes me think that? Well, we know Orkneyinga saga was compiled in Iceland around the turn of the thirteenth century, around 300 years after Sueno’s Stone was erected—meaning the stone was already old when the saga was compiled. And according to Dr Alexander Taylor, the saga was compiled from many different sources, including older sagas, oral tradition, folk-tales and hagiographies.

We know there was travel and exchange of ideas between northern Scotland and Iceland at the time the sagas were being compiled. We know there were dynastic ties and political alliances between earl Harald Maddadsson of Orkney and Caithness (r. 1139–1206) and the twelfth-century aristocracy of Moray, and that the saga authors operated in an aristocratic milieu.

We know from the Kiloran Bay boat burial that horses were buried with humans in an early medieval Scandinavian Scotland context. We also know there’s a strong human impulse to try to make sense of antiquities whose original context and purpose have been forgotten, by ascribing stories to them or seeing stories in their carvings.

Does all of this add up to the possibility that the story of Sigurd the Powerful and Máel Brigte ‘Tooth’ in Orkneyinga saga was partly inspired by a twelfth-century (or earlier) encounter with Sueno’s Stone, and an attempt to make sense of its already-ancient and perhaps already forgotten narrative?

In reality, this is the kind of thing that’s impossible to know or prove. But all the same, it’s quite thrilling to think that in the tale of Sigurd and Máel Brigte we see a glimpse of Sueno’s Stone in medieval times. Otherwise, the first description of it in the historical record only appears c.1640, with Robert Gordon of Straloch’s Nova Moraviae Descriptio.

More rabbit holes to explore

There may be nothing at all in this idea, but writing this blog has at the very least prompted me to look very closely at the battle scenes on the stone, which I’d found a bit of a daunting prospect before. And it’s also opened up a whole new warren of rabbit-holes for me to explore in future.

If anyone has any thoughts, as ever I would be very pleased to hear them!

References

Cross, Pamela J. Horse Burial in First Millennium AD Britain: Issues of Interpretation (2011)

Gordon, Robert. Nova Moraviae Descriptio (c. 1640)

Jackson, Anthony. The Symbol Stones of Scotland (1984)

McDonald, R. Andrew. ‘Soldiers Most Unfortunate’: Gaelic and Scoto-Norse Opponents of the Canmore Dynasty, c.1100–c. 1230, in History, Literature, and Music in Scotland, 700-1560 (2002)

Pálsson, Herman and Paul Edwards (trs). Orkneyinga Saga: The History of the Earls of Orkney. Penguin Classics (1978)

Romilly Allen, J. The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland, Volume 2 (1903)

Skene, William Forbes. Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban, Second Edition (1886)

Southwick, Leslie. The So-Called Sueno’s Stone at Forres (1981)

Taylor, Alexander Burt. A study of the Orkneyinga saga with a new translation (1935)

Jackson argues that this mismatch is an intentional part of the design, in which the number 7 plays a key role. I currently make the numbers 42 vs. 49, but that still preserves the mismatch and the number 7.

Interestingly, nobody to my knowledge has ever interpreted these figures as horses when writing about the stone: John Romilly Allen, Anthony Jackson and Leslie Southwick all saw them as human warriors fighting—although they didn’t have the benefit of these drawings.

Good fun, thank you!

Fascinating! And it's a theory that makes sense, even if ultimately it can't be proven either way.