Fathenechten: deciphering a medieval Nairnshire place-name

In which I try to figure out what a place-name mentioned in 1150 actually meant

If you’re a long-time reader of this Substack, you’ll know that a large chunk of my research into the early medieval Moray Firthlands consists of trying to identify and interpret early place-names. And I’m afraid I have yet another place-name mystery to untangle in this instalment.

If you’re a new reader, some context. Since documentary records don’t really start for much of Scotland until c.1150, place-names are one of the most important historical sources for the area around the Moray Firth in the later first millennium AD.

Place-names can give clues about how the land was settled and organised at that time, as well as how natural resources were exploited, how and where power was exercised, which languages were in use, where people gathered together, even who might have lived where.

But place-name research comes with many challenges. Before I get stuck into the name I’m currently puzzling over, I want to illustrate the problems by going back to the book that first inspired my love of maps, place-names and the early medieval period.

Place-names as plot device in Over Sea, Under Stone

I realised recently that I can trace my fascination with all of these things back to Susan Cooper’s children’s book Over Sea, Under Stone, which I first read when I was about 10.

The first book in Cooper’s Arthurian-themed The Dark is Rising sequence, it sees three young siblings, Simon, Jane and Barney, staying in the fictional Cornish fishing village of Trewissick (based on Mevagissey, not far from where I live now), at a house called the Grey House.

The kids find an ‘old manuscript’ in the attic of the Grey House, with a map that sets them off on a thrilling adventure—leading to the discovery of an important sixth-century artefact.

(For fellow early medievalists who haven’t read it, there’s a great skewering of academics in its Detectorists-esque epilogue.)

Crucially for the plot, Jane manages to decipher a place-name on the manuscript map, with the help of another map that she finds in an antiquarian guidebook to Trewissick.

Here’s the passage in question, slightly abridged.

The page [of the guidebook] showed a detailed map of Trewissick village, with every street, straight and winding, patterned behind the harbour that lay snug between its two headlands.

The Grey House was marked by name, on the road that led up to the tip of Kemare Head, then faded into nothing. But what caught her attention was the name written neatly across the headland: King Mark’s Head.

She unrolled the manuscript on the table. The words stared up at her, cramped and enigmatic: ‘Ring Mark Hede’. And she saw that the first letter of the first word, blurred with age and dirt, might not be an ‘R’ but a ‘K’. She gulped with excitement and took a deep breath.

King Mark’s Head: the same name on both maps. So that the map on the manuscript from the attic must be a map of Trewissick. The strange words must be an old name for Kemare Head.

The realities of place-name research

I can still feel the thrill I got from reading this as a 10 year-old, and realising that place-names are essentially encoded messages about the past, just waiting to be deciphered.

However, reading it again as a fifty-something PhD student, I see it does give a rather misleading impression of the level of skill required to tease meaning from place-names.

Luckily for Jane, the ‘old name’ for the headland turns out to be in modern English—her native language—and not, as one might expect, Old Cornish. And the key to interpreting it is somewhat handed to her on a plate, in the form of an antiquarian map with the ‘old name’ written on it.

In reality, place-name research, particularly in my study area of north-east Scotland, requires knowledge of a disconcertingly wide array of languages. That’s because it’s important to establish which language the name was originally coined in, so others can be ruled out.

Scotland’s complex linguistic history

Scotland has a very mixed linguistic history, with place-names coined in English, Scots, Norn, Gaelic, Old Norse, Old Irish, Old English, Pictish and Proto Indo-European. Identifying the right one (or ones, as many names combine words from two languages) isn’t always easy.

Partly this is because place-names become corrupted over time—just like ‘Kemare Head’ in Over Sea, Under Stone turns out to be a corruption of ‘King Mark’s Head’.

Partly it’s because we don’t know very much about the Pictish language, which is presumed to have been spoken in north-east Scotland until around 900 AD, when it appears to have been superseded by Gaelic. It seems to have been a Brittonic language similar to Old Welsh, but it’s hard to know how much to rely on Old Welsh as a guide to interpreting Pictish place-names.

And while a Gaelic word and a Pictish word might look similar, and come from the same Indo-European root, they sometimes they took on different meanings in the different languages.

All of these difficulties are relevant to the name I’m currently wrestling with, as we’ll see shortly.

The importance of early forms

The other difficulty is getting hold of early forms of the name. These are vital for understanding what language the name was coined in and what elements it originally contained.

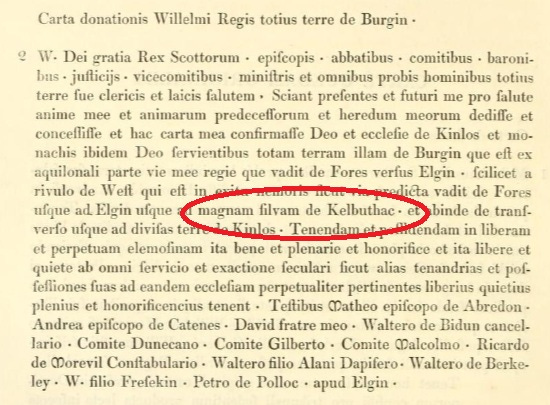

In this post, for example, I gathered all of the early forms of the name Kilbuiack, near Forres, to see if the ‘Kil-‘ was from Gaelic cill, meaning church. If so, it might mark the site of an early church. As it turned out, the earliest forms of the name have it as Kelbuthac, which, along with other charter evidence, indicates it’s from Gaelic coille—meaning a wood rather than a church.

In Over Sea, Under Stone, Jane had the good fortune of finding an ‘old manuscript’ with a map drawn on it, and ‘King Mark Hede’ written on the map, proving that Kemare Head was a corrupt form of the English name King Mark’s Head.

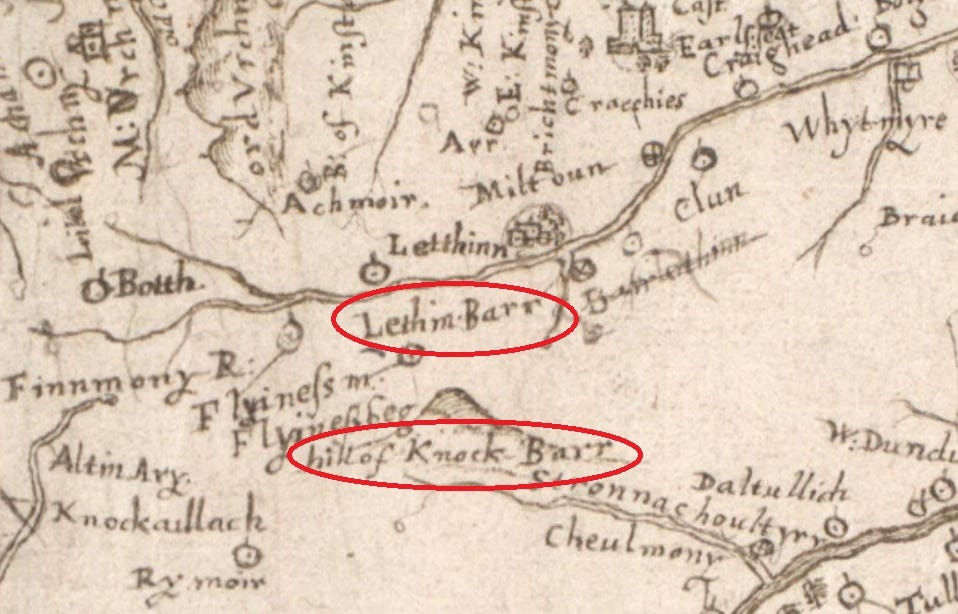

But Scotland’s early medieval names are much older than the oldest detailed map of the country, drawn by Timothy Pont in the 1590s. Although Pont’s map is a rich resource for the place-name scholar, many of the names he recorded had already changed a lot by his time.

The evidence of early charters

To get to the earliest forms, we have to go back further, to the earliest surviving land grant charters—which, in the case of Moray, date from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

But even here there are problems.

Firstly, even the earliest charters date from hundreds (or thousands) of years after the oldest names were coined. So the forms of many names have already changed by the time they enter the charter record, sometimes making the original form hard to discern.

Secondly, another 900 years have elapsed since the earliest charters were written, and some of the place-names they record are no longer easily identifiable. Sometimes the places no longer exist, and sometimes their modern forms are very different from their medieval forms.

Thirdly, the surviving early charter material for Moray is pretty thin. Some names are well represented, like the new burghs (Elgin, Forres, Auldearn, Nairn), and the parish churches whose teinds (tithes) were appropriated to support the canons of the new Elgin Cathedral.

But records of humbler places are much scarcer. So it’s often hard to establish how far a minor rural name goes back, and what language it was originally coined in.

A place-name mystery from c.1150

All of these issues are relevant for the name I’m trying to untangle. It only appears once in medieval records: in a charter of David I (r. 1124–1153) concerning two landholdings that are being transferred from Dunfermline Abbey to the newly-founded Urquhart Priory near Elgin.

The charter dates to 1150–1153 and versions of it appear in the Register of the Bishopric of Moray and the Register of the Abbey of Dunfermline.

In the Moray Register the two landholdings appear as:

Pethnec juxta Erin et scalingas de Fathenechten.

…and in the Dunfermline Register as

Pethenach iuxta Eren et scalingas de fathenechten.

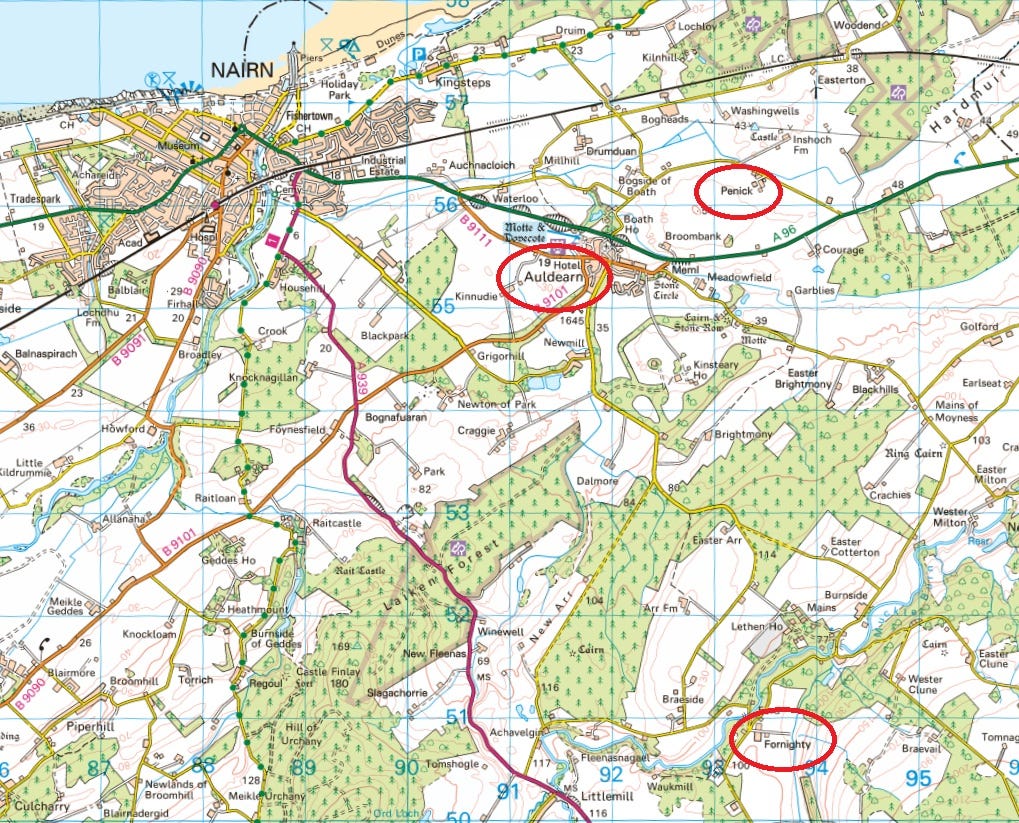

Eren is a very interesting name that I’ve written about before. It almost certainly refers to Auldearn, and appears to stand for Eireann, meaning Ireland.

Pethnec/Pethenach, according to the place-name scholar W.J. Watson, is Penick, now a farm just north-east of Auldearn. This seems correct as it’s described as ‘near Auldearn’ (juxta Erin).

The shielings of Fathenechten

But the name that interests me right now is Fathenechten. As the charter says, this was a shieling (scalinga) location—a temporary seasonal settlement, usually in an area of upland pasture, where cowherds would live along with their cattle in the summer months.

It’s the type of place that doesn’t often appear in early charters, in other words, and it’s interesting in itself as a glimpse of agricultural practice in twelfth-century Nairnshire.

Only two locations have been suggested for this name, as far as I am aware. Archibald Lawrie, who produced an edition of the earliest Scottish charters in 1905, thought it was also Penick:

Scalingae were sheils or sheilings, huts erected each summer for the use of those who tended the cattle sent to graze on the hills. Fathenechten may be the same as Pethenach.

This doesn’t really make sense, though, as the charters specify that they’re separate places. If they were the same place, it would probably read something like ‘Pethenach with its scalingas.’

In his 1926 book The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland, W.J. Watson proposed a more plausible location:

Fathenachten [sic] is probably Fornighty in Ardclach, the Gaelic of which is Achadh-ghoididh (? - ghoide, from goid, theft), apparently a different name for the same place.

Watson may have had local knowledge about the alternative Gaelic name Achadh-ghoididh, as I haven’t seen this name anywhere else. Francis Diack conducted an (unpublished) oral survey of Nairnshire place-names in 1920,1 so that may have been Watson’s source.

Unusually, Watson doesn’t comment about what the name Fathenechten itself actually means. He does, however, imply that it isn’t Gaelic—and this is what sparked my interest.

How Fathenechten developed into Fornighty

I’ve been thinking for a while that Fornighty might be a rare survival in Nairnshire of a Pictish place-name, dating back perhaps to the eighth century or even earlier.

I’m a historian, not a historical Celtic linguist, so trying to establish this without help is difficult to say the least. But it’s also a good test of my abilities (or lack of them!)

So, my first task is to find as many early instances of the name as I can. Unfortunately, names of minor places tend only to appear in charters when they change hands, and after Fathenechten is granted to Urquhart Priory in 1150, it doesn’t surface again until the Reformation.

In 1587, the lands that had belonged to Urquhart were made into a temporal lordship, granted by James VI to Alexander Seton, first Earl of Dunfermline. I haven’t found a list of the lands in that grant, but Fathenechten soon starts to change hands again, and a paper trail begins.

In the early seventeenth century, it turns up in two charters of the Grant family. The first, dated 1627, records a marriage contract between Sir John Grant of Freuchie and Lady Marie Ogilvie. Among the lands listed as part of the agreement include:

…the lands of Farnichtie and Newlands thereof, with the teindsheaves, in the barony of Farnen, lordship of Urquhart, and shire of Nairn, held of the Earl of Dunfermline…

‘Farnichtie’ here is Fornighty, the place Watson identified as Fathenechten.

Seven years later, Marie gives up her rights in various lands, apparently “out of her special love and favour” for her husband, so he can sell them to pay his various debts. Those lands include:

…the lands and barony of Lethen, Bellivat, Farnichtie and Clune…

It seems that John Grant’s rights in Farnichtie then went to a branch of the Brodie family of Brodie. A Chancery record of 1673 shows Alexander Brodie of Lethen inheriting a swathe of lands from his father, also Alexander Brodie of Lethen. Among them are:

…villa et terris de Fairnichtie… in baroniam de Fairnew et regalitate de Urquhart…

…the settlement and lands of Fairnichtie… in the barony of Fairnew and lordship of Urquhart...

Since Farnichtie/Fairnichtie clearly comes from the old landholdings of Urquhart Priory, it does seem a good bet that it is the Fathenechten of the 1150 charter, as Watson had proposed.

The only factor militating against this is that Farnichtie doesn’t appear on Pont’s map of c.1590, which otherwise records farms, mills, churches and settlements in detail.

Instead, Pont seems to show on the spot a place he calls ‘Lethin Barr’. Lethen Bar is the name of a hill to the south-east of Fornighty, but that’s shown on his map too. (Entertainingly, he labels it ‘Hill of Knock Barr’, meaning ‘hill of hill hill’!) So I’m not quite sure what’s happened here.

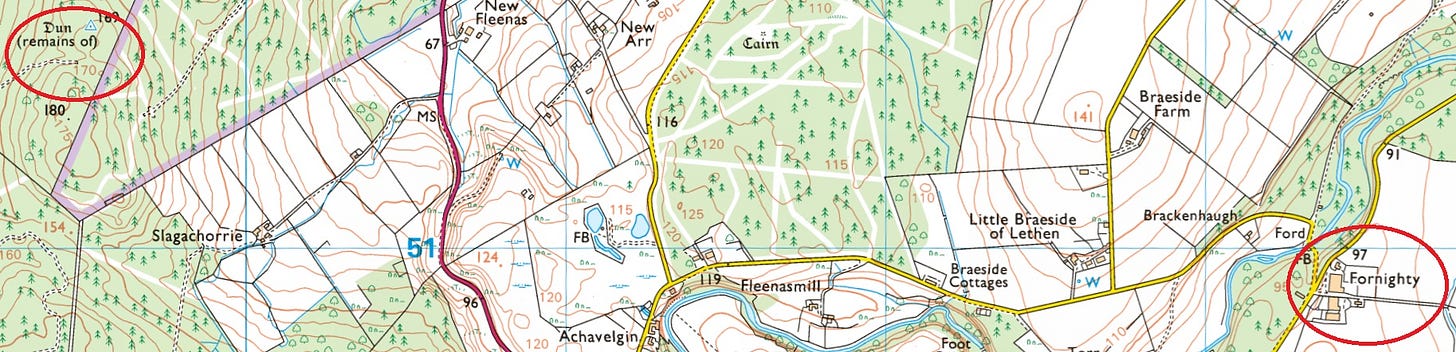

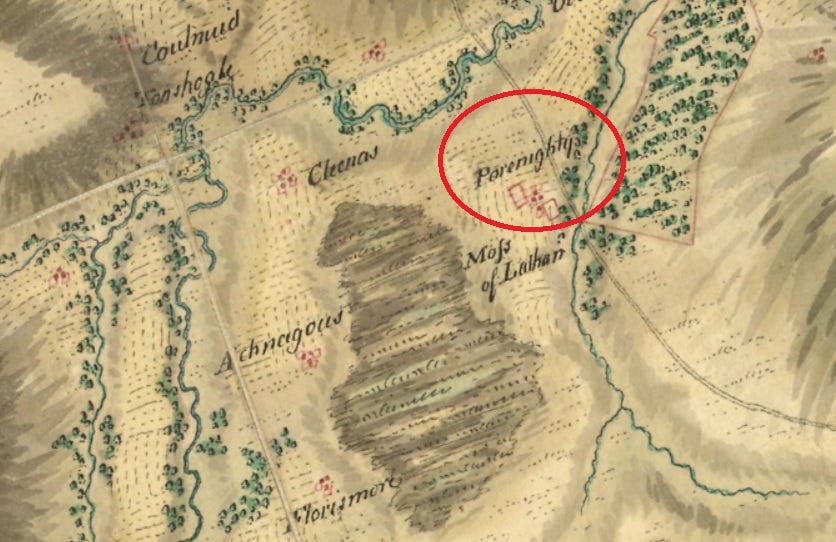

But if we can otherwise accept that Farnichtie is the same place as Fathenechten, we can chase it up to the present day via William Roy’s military map of Scotland from c.1750, which shows it rather idiosyncratically as ‘Porenighty’.

Finally, the first edition Ordnance Survey six-inch map of 1871 gives its modern form, Fornighty.

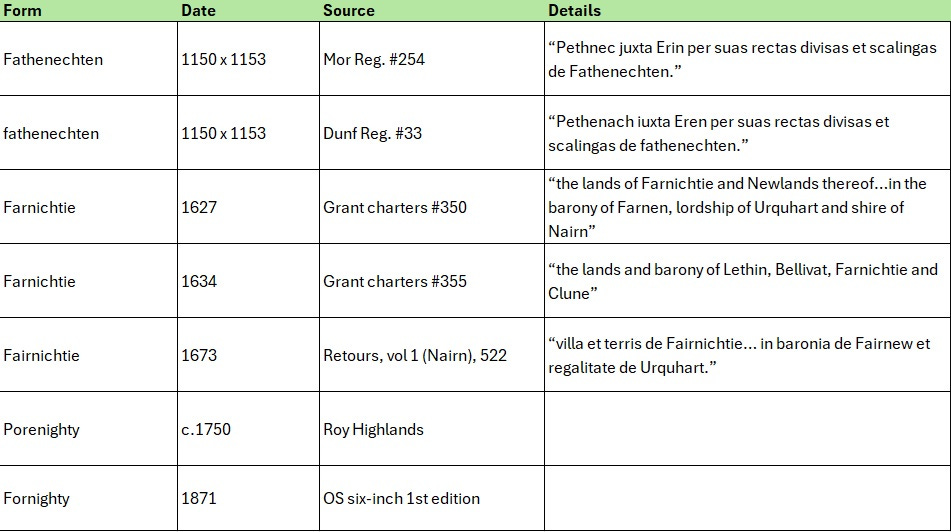

This gives us a table of forms thus:

A glimpse of an early medieval Pictish estate?

The modern forms show that the first element, fathe, developed over 700 years via far and fair into for, and the second element, nechten, developed via nichtie to nighty.

Swayed by the ‘r’ in the later forms, my first idea was that fathe might represent the fairly common—and potentially very interesting—place-name element foithir.

The meaning of this word varies from language to language. In Gaelic, it generally means a terraced slope. In early Irish, its meanings include ‘piece of unreclaimed valley or woodland’. Its equivalent in Welsh, godir, can mean ‘region, district’; ‘lowland, plain’; or ‘slope, declivity’.

In Pictish, it seems to have had an additional (or alternative) higher-status meaning. In volume 5 of his Place-Names of Fife, the toponymist Dr Simon Taylor noted that:

In eastern Scotland the word is found in several high-status names, such as medieval parishes.

He goes on to list a number of medieval parishes and baronies starting with foithir, which include Ferness (Fothervays) mentioned above, as well as Fedderate, Fetterangus, Fettercairn, Fodderty and Forteviot. He concludes that:

Given that all of these examples are in former Pictland, and that so many of them are of high-status places, it is possible that we are dealing with a Gaelic adaptation of a Pictish *uotir ‘territory’, perhaps some kind of administrative unit.

Although nobody has yet examined all of these Pictish *uotir sites in detail to try to establish what it meant, I’m mulling an idea that it denoted a kind of early medieval secular estate, with a fortified power centre, land and resources of various types, and outlying settlements.

The existence or otherwise of such estates is a contentious topic in early medieval history, but I’m quite swayed by an argument made by John Rogers in his 1992 PhD thesis that some estates of this nature were used to form parishes in the twelfth century.

If *uotir did mean estate, it might explain why so many parishes have foithir names. It also felt like a particularly appealing interpretation for fathe because of the second element, nechten.

The estate of Nechtan?

Surely this, I thought, is the Pictish personal name Nechtan. It appears in numerous place-names in Pictland, including Dunnichen in Angus and Dunachton in Badenoch (both meaning ‘Nechtan’s fort’), as well as Bunachton (‘Nechtan’s hut’) in Inverness-shire, and the obsolete Dalvanachtan (‘Nechtan’s davoch’) and Cadha Neachdain (‘Nechtan’s path’) in Easter Ross.

Nechtan was the name of at least two Pictish kings: Nechtan son of Uerb (r. 595–616) and Nechtan son of Der-Ilei (r. 706–724 and 728–729). Another Nechtan was abbot of the monastery of Nér (likely Fetternear in Aberdeenshire), whom the Annals of Ulster tell us died in 679.

Before I started training as a historian, I might readily have leapt from spotting the name Nechtan in Fathenechten to imagining that one or other of the King Nechtans had a base in Nairnshire—perhaps the vitrified fort known as Castle Finlay, or the dun a little to its east.

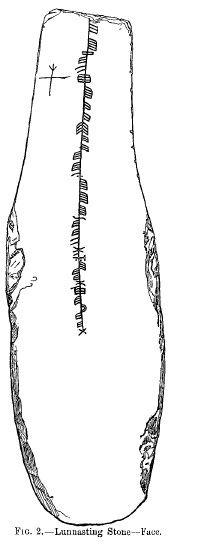

However, evidence of various types shows that Nechtan was a common name across Pictland. It even appears as far as north as Shetland, in an eighth or ninth-century ogham inscription on a stone from Lunnasting.

The inscription—as transliterated in 1995 by Professor Katherine Forsyth—reads:

ettecuhetts: ahehhttannn: hccvvevv: nehhtons

While the first three words haven’t been interpreted to anyone’s great satisfaction, there is a general consensus that the final word nehhtons represents the name Nechtan.

Nechtan’s Nairnshire estate

So my initial interpretation of Fathenechten was foithir-neachdain—a Gaelicisation of a Pictish place-name that I interpreted as ‘estate of Nechtan’.

That would put it alongside the only other name I’m aware of that has foithir + personal name: Fetterangus in Aberdeenshire, which first appears in a charter of 1208 x 1236 as Fetheranus.

I was imagining Nechtan as a similar individual to the Pictish pagan Emchath, who is converted to christianity by Columba in book 3, chapter 14 of Adomnán’s Life of St Columba.

Emchath is a man of standing, who has a household and an ager (Latin for ‘field’) at Urquhart on Loch Ness. Elizabeth and Leslie Alcock interpreted ager in this instance as ‘estate’, and found evidence of a sixth-century fortified site at Urquhart Castle, which they saw as Emchath’s stronghold.

I was busy placing my man Nechtan in a modest stronghold on the Hill of Urchany, overlooking his *uotir in the valley below: a small estate immortalised in the name Fornighty.

But in the end I had to let this whole idea go.

Back to the drawing-board

The golden rule of place-name research is that the early forms of the name are a better guide to its make-up than the later forms. And in both versions of the 1150 charter, fathe has no ‘r’ at the end and the first vowel is ‘a’ rather than ‘o’.

This is a bit of a deal-breaker, because foithir/*uotir is made up of two separate words, fo meaning ‘under’ and tír meaning ‘land’.

While the vowel sound might have varied through dialect, the lack of an ‘r’ would suggest that either that the twelfth-century scribes didn’t know the word they were writing—unlikely, as foithir was pretty common—or that I’m on the wrong track.

So even though the later forms—Farnichtie, Fairnichtie, Fornighty—do have an ‘r’ in the first element, I should really admit defeat and look elsewhere for the origin of fathe.

An online dictionary search reveals that in Old Irish, fath means ‘cause’, ‘composition’, ‘heat’ or ‘garment’, while fadan means ‘ear’. None of these seem appropriate for place-names. The Gaelic dictionary, however, offers the archaic fàth, meaning ‘open ground’ or ‘vista perspective’.

Fornighty doesn’t have a vista as it’s in the valley, but ‘open ground’ could work, especially as we know Fathenechten was summer pasture in 1150. In which case, Fornighty may not have been ‘Nechtan’s estate’ but ‘Nechtan’s clearing’.

While another principle of place-name research is that the most mundane interpretation is likely to be the right one, I still find this rather unsatisfactory.

If fàth was widely used for ‘open ground’ it should appear in other place-names, but I can’t find a single other place-name starting with this element. If Fathenechten had been a shieling location from its beginning, we should expect the term àirigh or ruighe rather than fàth - both terms used very widely in shieling place-names in Scotland.

A frustrating dead-end

But without a grounding in historical Celtic languages, this is as far as I can go. Unlike Jane in Over Sea, Under Stone, my place-name research has led not to a priceless early medieval relic, but to a frustrating dead-end.

But as always, documenting this rabbit-hole has been a valuable exercise. It’s forced me to track down sources, study them in detail, critically assess their reliability, and abandon a pet theory—all vital skills for the historian.

So once again, thank you very much for coming on this journey with me, and if you have any comments or insights, I’d be very happy to hear them.

References

Elizabeth and Leslie Alcock, ‘Reconnaissance excavations on early historic fortifications and other royal sites in Scotland, 1974-84’ (Proceeding of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1993)

Bannatyne Club, Registrum de Dunfermelyn (1842)

Susan Cooper, Over Sea, Under Stone (Jonathan Cape, 1965)

Katherine Forsyth, ‘The Ogham Inscriptions of Scotland: An Edited Corpus’ (PhD thesis, Harvard University, 1995)

William Fraser, The Chiefs of Grant, volume 3: Charters (1888)

Cosmo Innes (ed.), Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis (Bannatyne Club, 1847)

King George III Records Commission, Inquisitionum ad capellam domini regis retornatarum, vol I (1811)

Archibald C. Lawrie, Early Scottish Charters prior to A.D. 1153 (University of Glasgow, 1905)

Roddy Maclean, Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area (NatureScot, 2021)

Peadar Morgan, ‘Ethnonyms in the Place-Names of Scotland and the Border Counties of England’ (PhD thesis, University of St Andrews, 2013)

Timothy Pont, Mapp of Murray (c.1590)

John Rogers, ‘Formation of the parish unit and community in Perthshire’ (PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 1992)

William Roy, Military Survey of Scotland (c.1750)

Richard Sharpe (ed.), Life of St Columba by Adomnán of Iona (Penguin Classics,

Simon Taylor with Gilbert Márkus, The Place-Names of Fife Vol. 5 (Shaun Tyas, 2012)

W.J. Watson, The Place-Names of Ross and Cromarty (Northern Counties Printing and Publishing, 1904)

W.J. Watson, The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (Blackwood & Sons, 1926)

I came across the reference to Diack’s research in Peadar Morgan’s 2013 PhD thesis (see bibliography), so thanks Peadar for inadvertently shedding light on this mystery!

That stone is amazing! So I presume that is Pictish writing, vertically ?!

Just over a year ago I looked at the provenance of English place names (https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.12850). In a few months I will be starting on a Scottish version (as wells as Welsh and Irish). Hopefully this may be of use.