Wood or church? Deciphering the place-name 'Kilbuiack'

In which I try to figure out if a now-lost Moray place-name is relevant to my research.

It’s December, which means the lecture that I’m giving to the Pictish Arts Society in February is suddenly not that far away.

My topic is the landscape context of Sueno’s Stone, a 6.5m-tall carved cross-slab of the ninth or tenth-century AD, whose origin, meaning and purpose have confounded historians, archaeologists, map-makers and antiquarians for over 350 years.

Ostensibly, Sueno’s Stone stood alone in its landscape, as there are no archaeological remains in its vicinity to suggest an early medieval church, building or settlement to which it might once have ‘belonged’.

However, the wider landscape around the stone has been seriously under-investigated for clues that might shed more light on its original context. So this is what I’ve been looking into—both for my forthcoming lecture and for my MA dissertation which I (finally!) start writing in January.

Looking at the place-name evidence

One big strand of this research is looking at the place-names around Forres, to try to identify names that might date back to the later first millennium AD, and which might help to contextualise the stone: names like Kilbuiack, which I’ll be investigating in this blog.

I find this research quite daunting, for three reasons. Firstly, the fertile hinterland of the Moray Firth has been continuously and intensively settled since at least the Bronze Age. Place-names have come and gone as human activity and settlement patterns have changed over the centuries.

The older names still in existence today are just those that have survived the continuous change in land use and the sometimes-cataclysmic natural changes to the landscape. Very many more have been lost, either because they were no longer useful,1 or—like the farms and laird’s house that once stood in what’s now the Culbin Forest—because their places were engulfed by sand, river, or sea.

Finding these lost names means digging into maps and records going back to the twelfth century—not an easy task.

The many languages of Moray

Secondly, the place-names of the area reflect changes in the languages spoken by the people living here. To ancient pre-Celtic names2—like ‘Earn’, the old name for the River Findhorn—were added Brittonic/Pictish names, like Forres itself. Then, sometime during the first millennium AD, Gaelic speakers arrived from the west, starting a new stratum of names, like Kinloss and Findhorn.

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Scots and English speakers came from the south to live in the new burgh of Forres and Cistercian abbey at Kinloss, adding two more linguistic strata to the area. The presence of the monks in particular can be traced all over the lowest-lying parts, with their tell-tale ‘granges’ (monastic barns) giving their name to East Grange, Grange Hall and Mill of Grange.

This adds up to five languages—and even a sixth and seventh, as there are (or were) also Latin and Norman French place-names in the area, as we’ll see later.

[UPDATE 5/12: Thanks very much to Peadar Morgan for clarifying in the comments that what I thought were Latin and Norman French names are actually Gaelic (translated into Latin for a charter) and Older Scots respectively.]

Of those seven five, I’m only really competent in English and (at a push) Scots, so despite my best efforts, the Pictish and (particularly) the Gaelic names present endless challenges for me.

Thirdly, unlike other areas of Scotland, there’s never been a comprehensive place-name survey of Moray. This means I’m having to cobble my research together from partial analyses done previously by scholars like W. J. Watson, W.F.H. Nicolaisen, Simon Taylor and Thomas Owen Clancy; from comparing names with similar or identical names elsewhere that have been analysed; and from frequent recourse to the extremely helpful toponymists in the Scottish Place-Names Facebook group.

Tracing names back through time

One thing I learned quite early on is that to understand the age and original meaning of a place-name, you can’t start with its modern-day incarnation. Names become garbled and remoulded over centuries, especially as language and land use change. Instead, you have to trace the name back as far as you can in the records, to try to form as clear a picture as possible of its original form.

Early forms provide a better idea of the name’s original constituent elements, which makes it easier to identify which language it was coined in, and what those constituent elements originally meant.

And so it is with a name I’ve been particularly interested in recently, and which has only recently faded from the landscape around Forres: Kilbuiack.

This name caught my attention because I’m looking for evidence of an early medieval church to which Sueno’s Stone might have been attached. Many early church names in Scotland begin with the element ‘Kil-,’ from Gaelic cill or (monk’s) cell, so I wondered if Kilbuiack might be a church name.

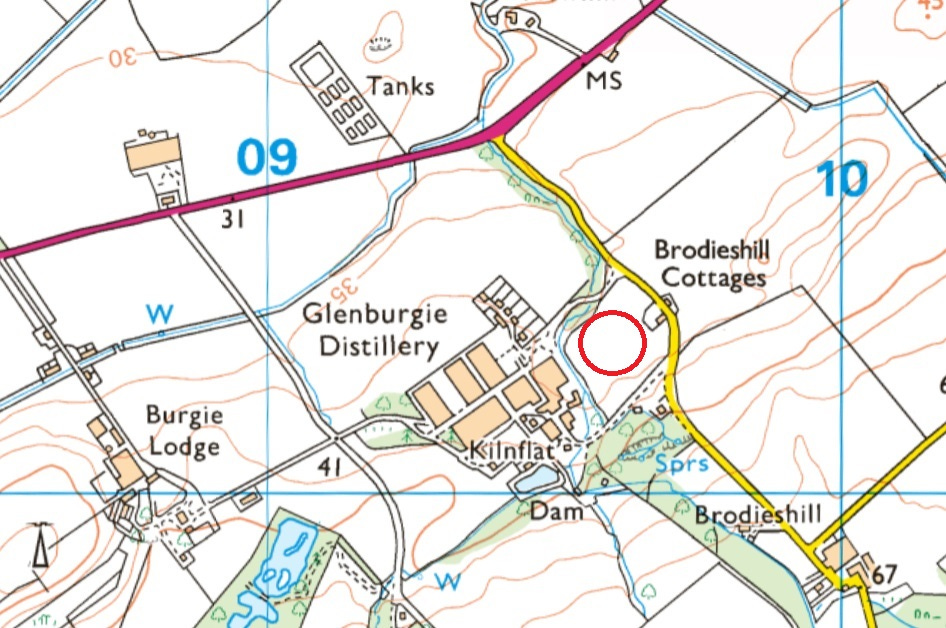

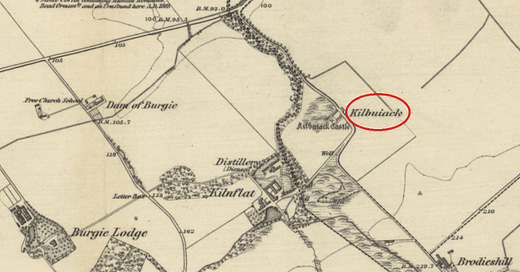

Today, the name has disappeared from the map, superseded by the English name Brodieshill Cottages. But as the maps below show, it was still being marked in 1970 as the site of a fifteenth-century castle, and in 1870 it was still giving its name to the farm that is now Brodieshill Cottages.

Kilbuiack through the ages

The method, then, is to trace the forms of the name back through maps and written records, to try to gain an understanding of its age and original significance. Luckily, Kilbuiack has an excellent textual and cartographical pedigree stretching back to the very first charters relating to this part of Moray.

Here’s a selection of the references I’ve found, in reverse chronological order:

1970 Kilbuiack (Ordnance Survey)

1870 Kilbuiack (Ordnance Survey Name Book)

1775 Kilbuyack (Lachlan Shaw, History of the Province of Moray)

1673 Kilbuyack (Inquisitionum ad Capellam Domini Regis Retornatarum)

1630 Kilboyok (as above)

1623 Kilboyock (as above)

1590 Kilbuyack (Timothy Pont, Mapp of Murray)

1574 Kilboyok (Records of the Monastery of Kinloss)

1283 Kylbuthock (Aberdeen-Banff Illustrations)

1187x1203 Kelbuthach (Records of the Monastery of Kinloss)

1165x1214 Kelbuthac (Records of the Monastery of Kinloss)

The first thing to note is that the name survived into the late 20th century remarkably unchanged from its first appearance in charter records in the late 1100s or early 1200s. And given that these charters are actually the oldest surviving written records for this part of Moray, the name itself may well be much older.

However, if I’m looking for firm evidence that the first syllable, ‘Kil,’ denotes an early Gaelic church, the oldest forms don’t provide it. The two earliest references start with ‘Kel,’ not ‘Kil,’ and they both relate to woodland: the magnam silvam de Kelbuthac/Kelbuthach, or forest of Kelbuthac. On this evidence, it would seem more likely that ‘Kel’ is from Gaelic coille (‘wood’) not cill (‘church’).

This is where the second element becomes important. If it was a church (despite its woodland setting), the second element ought to relate in some way to its dedication. Most Kil- places that were early churches have a saint’s name as their second element: Kilbride is the church of St Brigit, Kildonan the church of St Donnán, Kilfinnan the church of St Finan, and so on. Sometimes the name records the actual founder; more often it’s the name of the saint the church was dedicated to.

Buthac: a personal name, or a stream with healing powers?

What then can we (by which I mean people who know Gaelic and Middle and Old Irish, not me) make of the element buthach or buthac? This is where it’s interesting to compare with other place-names whose meanings have been parsed before. W.J. Watson offers some clues in his 1926 book The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland.

Firstly, in relation to ‘Kynbethoc’ (later Kinbattoch in Aberdeenshire), he says:

The vicar of Kynbethot (read -oc) in the deanery of Mar is mentioned in 1275; Kynbethoc appears as a parish in the taxation of benefices c. 1366; in 1507 it is Kilbethok. Bethóc, now Beathág, is a woman’s name; here it may be the name of a saint who is not known otherwise. Dolbethoc, ‘Bethóc’s meadow, was granted to the Culdees of Monymusk by Gilcrist, earl of Mar.

This seems interesting. Could the buthac in Kelbuthac also be a personal name? If it is, it doesn’t seem to be the same name as Watson’s lost St Bethóc, as it always appears with a ‘buth’ and never with a ‘beth’. And if it is a personal name, it could still relate to a forest as much as a church, just as Watson’s Dolbethoc is ‘Bethóc’s meadow.’ So perhaps not much help.

However, in relation to ‘buth,’ there’s this very interesting discussion relating to stream names:

Aberbuthnot, now Arbuthnot in Kincardineshire, is Aberbothenoth, 1242, Abirbuthenoth, Aberbuthenot, 1282/3, etc. Here ‘Bothenoth’ is the name of the stream close to St Torannan’s church, and is for the genitive of Buadhnat, ‘little one of virtue,’ lit. ‘little triumph, little virtue;’ in other words, it was a holy stream possessed of healing power. Similarly the stream which enters the sea in front of Máel Rubha’s church of Loch Carron is called Buadhchág, ‘little one of virtue;’ it also was a sacred stream of power. [my emphasis]

And he goes on:

So too in St Kilda and in Barra there are wells called Tobar nam Buadh, ‘the well of virtues’… The bell of Cill Chuimein, called am Buadach, ‘the one of virtue,’ conferred on the water of Loch Ness the virtue (buaidh) of curing cattle.

As I’ve said, I’m not a Celtic linguist at all. But to me there does seem to be a strong affinity between some of these names and the ‘wood’ or ‘church’ of buthac at Kilbuiack. Indeed, Máel Rubha’s holy stream of Buadhchág at Loch Carron feels like it may almost be the same word.

So if I was to propose that the buthac in Kelbuthac refers to a water-course believed to have healing properties—whether attributed to the holy power of a Christian saint, or to an earlier, pagan source of healing power (or indeed both), is there any other evidence I could present to support that idea?

A site by a stream, and a well with a resonant name

Well, there are two things. Firstly, the site which was later occupied by the fifteenth-century castle of Kilbuiack sits right beside a stream called the Den Burn, a tributary of the Kinloss Burn. Kilbuiack could therefore hardly be much closer to a watercourse.

Secondly, it might be useful in this context to think again about the well called ‘Tubernafein,’ or Tobar na Feinne, that I looked at in October.

The precise location of this well, which is mentioned in a charter of 1221 to Kinloss Abbey, isn’t known. However, the charter also refers to two other boundary-markers on the same piece of land, and these markers are described as ‘Runes’—‘Runetwethel’ and ‘Rune Pictorum.’

A later charter from 1283 refers to a piece of land called in Norman French Older Scots ‘Le Runys,’3 which seems to be the same land as that described in the 1221 charter mentioned above. And in this charter, the land is said to be at ‘Kylbuthock’ (Kilbuiack).

By considering these two charters together, a reasonable case can be made that Tobar na Feinne (along with ‘Runetwethel’ and ‘Rune Pictorum’) was somewhere near Kilbuiack. That’s important because its name likely refers to the Fianna, the mythological hunter-warrior companions of Fionn mac Cumhaill, or Finn MacCool.

As such, it may also have been associated with healing powers, as John Murray, in Literature of the Gaelic Landscape, suggests for another Tobar nam Fiann in Glenshee:

In Gleann Beag – Little Glen, just to the east of the mountain [of Bheinn Ghulbainn] is Tobar nam Fiann – the Well of the Fianna, where Fionn might have filled his golden cup intended off and on for [the healing of] Diarmaid, as Fionn’s mood swings alternated.

So at Kilbuiack we have a possible stream with healing powers, close to a possible well with healing powers. It certainly feels as if there was something special about this gently sloping hillside location, even without considering the significance of the ‘Runetwethel’ and (especially) the ‘Rune Pictorum’ located nearby. And the idea of a healing stream winding through the medieval forest of Kelbuthac sounds actually delightful: a far cry from the vast acres of barley fields that cover this area today.

Conclusion: No church, but a glimpse of the medieval landscape

To sum up, I started out thinking that because its name starts with ‘Kil,’ Kilbuiack might have been the site of an early medieval church, and possibly one associated with Sueno’s Stone. However, tracing its name back to its earliest mentions in the late 12th or early 13th century revealed that its first element was at that time ‘Kel’ not ‘Kil’, and thus more likely to refer to a wood than a church.

Comparing the second element buthac to other place-names with a similar element suggested it could be Gaelic Buadhchág, which elsewhere refers to a holy or healing stream. A now-lost well in the same area, named after the mythological Fianna, also suggests healing powers. But while such streams are elsewhere associated with early churches, the church isn’t usually named after them.

Therefore, my research suggests that the name Kilbuiack referred to a wood (likely the magnam silvam de Kelbuthac mentioned in the earliest charters), through which a stream believed to have healing properties (likely the still-extant Den Burn) flowed.

While this particular rabbit-hole hasn’t turned up an early church site associated with Sueno’s Stone, it’s definitely helped me to ‘see’ the medieval landscape around Forres and Kinloss more clearly—something I once thought was an impossible task. If anyone has any thoughts, I’d love to hear them.

References

Murray, John. Literature of the Gaelic Landscape: Song, Poem and Tale. Whittles Publishing, 2017.

Nicolaisen, W.F.H. Names in the Landscape of the Moray Firth. Scottish Society for Northern Studies, 1993

Pont, Timothy. Mapp of Murray. c 1590

Shaw, Lachlan. History of the Province of Moray. William Auld, 1775

Stuart, John. Records of the Monastery of Kinloss. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1872.

Ross, Sinclair. The Culbin Sands: A Mystery Unravelled. Scottish Society for Northern Studies, 1993.

Watson, W.J. The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (new edition). Birlinn, 2004.

A rather glib way of saying that many place-names in this part of Scotland have disappeared due to the mechanisation and industrialisation of farming, resulting in the loss of small farm settlements and agricultural livelihoods.

A pre-Celtic origin for this name is proposed by W.F.H. Nicolaisen in ‘Names in the Landscape of the Moray Firth’ (1993), p 260-261. I’ve added it to the bibliography.

The People of Medieval Scotland database tentatively identifies ‘Le Runys’ as Rheeves, a property at NJ 11051 60229. However, Rheeves, which in the 17th century was called ‘Ruiffis,’ was not part of the land owned by Kinloss Abbey at its dissolution (Retours). The Abbey did, however, own property at ‘Nether Ruiffis’ - now no longer extant but which, judging by its name, was downslope from Rheeves, and thus in the vicinity of Kilbuiack. I would suggest that ‘Le Runys’ should be identified with this ‘Nether Ruiffis’.

Great to have something to look forward to in February - it's usually such a gloomy month!

Well argued and, as ever, very interesting, Fiona. As I may have mentioned before re Rune Pictorum, in the accompanying database to my 2011 thesis I said, "[r]ather than a loan word in untypically incorrect Latin grammar, this appears to be undeclined ScG n.m/f. raon 'field' in Older Scots orthography. The grid reference is supplied by Sueno's Stone, (re-)erected at the apex of a spur of the parish of Rafford MOR near Burgie. Translation of the Gaelic ethnonym is assumed. The REM interpretations comes from a MS translation of four names from Gaelic to Older Scots which was added to the original charter; but interpretation as 'cairn' has no obvious basis. The plural interpretation of rune in REM may be seeking to make the reference agree with Latin grammar." As to whether the name is directly related to the stone, I must admit I like your identification of the name as part of Runys, and so likely not in its immediate vicinity after all.

A couple of wee points that irked, though (sorry!). 1) I don't think you can describe Runys as a Norman French name, despite the article "le". This is OSc le, lie, often found as a loan word from Latin in records: see https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/dost/le_def_art. 2) How certain are you that Èirinn ~ Earn, as applied here as opposed to its probable original in Ireland, is pre-Gaelic, let alone pre-Celtic...?

PS Many thanks from an earlier post for locating Inchdemmie more accurately than I could from Pont. In fact I see the name survives - or has been resurrected - in the newish Inchdemmie Villa as shown on OS 1:10k. A pair of ancestors were recorded as being in Inchdemmy in 1753, which probably incorporates their croft of 1748 Colls crooks, 1750 Collyscrooks, 1753 Collys Crook (v. DOST cruke '4. A curved or crooked piece of ground; a corner or nook. Chiefly in the names of special portions of land.')