Military or monastic? Deciphering the 10th century bridge at Kinloss

In which I try to work out what a bridge mentioned in the early medieval records was like and what it was for

The medieval Scottish king-lists relate how king Dubh of Alba was murdered in Forres in 966 AD, and his body hidden under the bridge of Kinloss, in Moray.

As far as I know, no scholar has questioned the existence of a bridge at Kinloss in the 10th century, but since I first started researching early medieval Scotland, it’s always stuck out for me.

I’ve written about the bridge before in relation to a theory about Sueno’s Stone, but in this blog I want to really get to grips with the bridge itself. What kind of bridge was it, what did it cross, and what was its purpose?

Two starting assumptions

I’m going to start with two basic assumptions, because otherwise I’ll end up going round and round in circles, building theories on top of theories:

Assumption 1: A bridge did exist at Kinloss in 966 AD, as related in the Scottish king-lists.

Rationale: Professor Dauvit Broun has shown that a lot of detail was added to the king-lists in the 12th century, with the aim of discrediting the men of Moray. However, Dr Neil McGuigan thinks the bridge detail is likely to be authentically 10th century, as it would serve no political purpose to add it later.

Assumption 2: Sueno’s Stone was erected sometime between 850 and 950 AD.

Rationale: This is the dating proposed by art historians, based on an analysis of the art style of Sueno’s Stone in comparison with other sculptured stones and illuminated manuscripts.

For the purposes of this blog, this means that Sueno’s Stone was either already in situ by the time the bridge was constructed, or was erected around the same time as the bridge was constructed.

With these two assumptions, I can attempt to answer some questions about the bridge:

What kind of bridge might it have been?

When I started my research, I was sceptical about whether bridges even existed in this part of Scotland in the 10th century. My assumption was that water-courses would have been forded or crossed by boat.

I knew the Romans had built bridges in Britain, but Moray was never occupied by the Romans, and I hadn’t heard of any Pictish bridges being found by archaeologists.

But when I began to look into it, I discovered that there were definitely bridges and bridge-like structures in the north-east of Scotland in the early medieval period.

One was at the Pictish monastery of Portmahomack in Easter Ross. Archaeologists led by Prof Martin Carver discovered the remains of a stone bridge that crossed an artificial water-course separating one side of the monastic site from the other.

A paved road with kerbs and ditches led down the slope from the cemetery hill to the bottom of the valley. It was taken across a bridge to the west of the dam, composed of massive capstones, like a clapper bridge.

Martin Carver has dated this bridge to 700-800 AD, during the monastery’s short 100-year life-span.

Another example is the crannog (lake dwelling on an artificial island) in Loch Kinord in Aberdeenshire. It had a causeway to the lake shore built on wooden piles, which archaeologists led by Dr Michael Stratigos have dendrochronologically dated to the 10th century.

So stone clapper bridges and wooden causeway-type bridges were in existence in northeast Scotland in the late first millennium, along with the engineering skills needed to build and maintain them. A bridge at Kinloss, then, wasn’t necessarily exceptional.

What did it cross?

Even if there were bridges, I figured, why would there be a bridge at Kinloss? The only water-course here is the tiny Kinloss Burn, which is narrow enough to jump over, or cross with a single plank of wood – surely not big enough to serve as a hiding place for a body.

My mistake was to assume that the water-courses present around Kinloss today are the same as they were 1,200 years ago. But in fact the southern shore of the Moray Firth has undergone dramatic changes over the centuries – due to longshore drift, coastal erosion, severe storms and sand-blow. Entire villages have been drowned by the sea and subsumed by sand.

And the changes haven’t just been due to natural forces: humans have had a huge hand in it, too. From the 12th century to the 19th, the whole of the Laich of Moray was progressively drained to create arable land.

In the 10th century, the fertile plain of the Laich – including the area between Forres and Kinloss – would have been mostly made up of shallow lochs and salt marshes. The area abounds with place-names containing the element ‘inch’, meaning ‘island’ – indicating where patches of higher and drier ground rose above the mire. Two lie between Forres and Kinloss: Whiteinch and Inchdemmie.

More moving rivers

There are also hints that the three main water-courses in the area once took different routes. The idea that in the 10th century the River Findhorn flowed far to the east of its current course still seems far-fetched to me, although scholars like Alasdair Ross and Barri Jones have given it credence.

More interesting are the hints that the Mosset Burn and the Kinloss Burn changed course in or after the 12th century. The foundation charter of Kinloss Abbey is lost, but later documents record that David I’s initial grant of land to the abbey in 1150 comprised:

The land which the king himself perambulated as the brook falls into Massat, and as the marsh goes down to the wood; as also the land on which the Scots mill stood, with the fishings, and the land of Eth [...] and a net in the water of Eren, and the wood of Inchedamin.

Even as someone who knows the area well, making sense of this is difficult. The ‘brook’ must surely be the Kinloss Burn, which passes through the abbey grounds. But the grant seems to say that the Kinloss Burn originally fed into the Mosset Burn (‘the brook falls into Massat’), whereas today both burns drain separately into Findhorn Bay, about a kilometre or so apart.

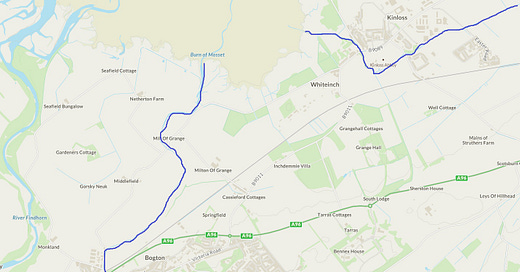

Both burns do show signs of artificial water management, though. The Kinloss Burn makes an abrupt series of turns as it passes by the abbey, while the Mosset Burn also makes four abrupt turns to pass through Mill of Grange (see map below).

An undated medieval charter records that the monks of the abbey had a licence to redirect the burn of Mosset, which was renewed in 1309.

The monks of Kinloss may therefore have redirected both burns: the Mosset to power the Mill of Grange, and the Kinloss Burn to provide running water and sanitation for the abbey. Had they not been redirected, it’s possible they might have met before discharging into Findhorn Bay. That might make the existence of a bridge at Kinloss in the 10th century more plausible.

What was its purpose?

Bridges don’t just appear out of nowhere – they’re civil infrastructure projects that have to be planned, built and maintained. So who wanted a bridge to be built at Kinloss, and why?

From reading up on early medieval bridges, three possible answers emerge:

1. The bridge was part of a military network

In the Saxon kingdoms, the 9th and 10th centuries saw a flurry of royally-sponsored bridge-building.

Alfred of Wessex, his son Edward the Elder and daughter Æthelflæd of Mercia all set about building networks of fortified towns (burhs) with connecting roads and bridges, as a means to mobilise troops, decentralise resources (ARPANET-style), and defend against Danish attack.

Alfred had been inspired by a similar scheme in Francia, where, according to David Harrison:

Charles the Bald had initiated a policy of building forts and bridges at key places along major rivers in north-west France to block the passage of viking boats.

As the Moray Firth coast was also susceptible to viking attacks, could the bridge at Kinloss have been part of a similar defensive system?

It’s not usually a good idea to try to compare the kingdom of Alba with Saxon England and Carolingian Francia, as the latter two polities had the kind of state administrative structures and monetary economies that seem to have been lacking in northern Scotland before David I’s accession in 1124.

But all the same, as the royal houses of Pictland and Dál Riata were both wiped out in a particularly catastrophic battle against the Northmen in 839, the incoming Gaelic ruling dynasty of Cináed mac Alpin might have wanted to put up some defences to avoid the same fate.

Maybe the bridge was part of a defensive system to prevent vikings from coming upriver (but which river?) Or maybe it was part of a military routeway between Sueno’s Stone and the great Pictish fort at Burghead (see video below by the University of Aberdeen’s Northern Picts Project), which was occupied until it was burned down sometime between 930 and 980.

The antiquarian Hugh W. Young did find part of an ‘ancient’ paved road leading away from Burghead fort, but not far enough to know in which direction it was heading. Christine Clerk notes that this may have been a Cromwellian military road, rather than a remnant from the 10th century.

Alastair Fraser recently suggested in a comment on this blog that the place-name Cassieford, on the modern road from Forres to Kinloss, could be a clue – which is intriguing, even if ‘ford’ is English, so likely to be 12th century or later.

(UPDATE: Thanks to Hector MacQueen, who in a reply to Alastair’s comment above has provided a highly plausible etymology for Cassieford (C17th ‘Calsafuird’) as ‘causewayford’. That would certainly suggest a post-12th century causeway - with ford - along the current route of the Findhorn Road out of Forres.)

2. The bridge was part of an ecclesiastical site

A much better parallel for the kingdom of Alba is contemporary Ireland, with which 9th and 10th-century kings of Alba – themselves descendants of Irish kings of Dál Riata – had close relations.

And it turns out that early medieval Ireland was dotted with bridges. Professor Katherine Forsyth pointed me towards the bridge over the Shannon at the early medieval monastery of Clonmacnoise, which has been securely dated to 804 AD. Archaeologists even found woodworking tools on the riverbed which may have fallen into the water during construction.

That led me to a blog by Dr Charles Mount, which starts:

Standard reference works make no mention of bridges. […] It has been assumed that most travel required the fording of rivers at crossing points. However, analysis of the Irish Annals […] indicate that there were bridges throughout Ireland in the Medieval period, built both by the native Irish and by the later Anglo-Norman settlers.

Dr Mount goes on to say that when bridges are mentioned in the annals, it’s usually because they were serving a military purpose or because there was a battle there. The earliest mention of a bridge is from 924 AD, when Muircheartach O’ Niall defeated a force of vikings at Cloone in Co. Leitrim.

Located on an early medieval routeway, the bridge at Clonmacnoise may have served one of two purposes, according to the University of Memphis civil engineering blog:

It may have been constructed to enable the growing monastic population to travel easily back and forth to their agricultural estates on the west side of the river, or to enable pilgrims to come easily to the monastery. Alternatively [it] may have been constructed through royal patronage, as part of the aggressive political and military expansion of Connacht kings during the period.

Could the bridge at Kinloss have been related to a monastic establishment pre-dating Kinloss Abbey? After all, someone would have had to build and maintain it, and a community of monks living nearby would be ideal candidates.

The Abbey’s foundation legend says it was built on virgin ground, but according to Professor Richard Oram (with whom I had a lovely chat on LinkedIn), this should be taken with a pinch of salt. It’s more likely that David I had the abbey built on a pre-existing site, to stamp his authority on the rebellious region of Moray. In his book on Malcolm Canmore, Neil McGuigan writes:

In the twelfth century, after a failed bid by Áengus mormaer of Moray to install Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair as king, the victorious David I took direct control of Áengus’s land and founded a Cistercian monastery near Forres, Kinloss Abbey. Situated on the edge of such an important Viking Age centre, it is likely that Kinloss Abbey’s Cistercians took over from an earlier monastic house, perhaps one of Pictish origin.

That said, there’s no evidence of an earlier monastery on the Kinloss Abbey site. Had there been one, we might have expected fragments of Pictish sculpture to have turned up there, as they did at Kinneddar. But only one fragment of early medieval carving has ever been found near Kinloss, and it’s probably a red herring.

3. The ‘bridge’ was a causeway or jetty

A third possibility is that the bridge wasn’t actually a bridge, but a similar sort of structure; perhaps a causeway or jetty.

In late 10th century Denmark, king Harald Bluetooth ordered the building of the Ravning Bridge, which was not strictly a bridge but a 760m-long wooden causeway that created a dry route through water-meadows by the Vejle River.

The site of this bridge, only 10km from the royal seat at Jelling, with its massive stone ship burials, has led archaeologists to think that the two are connected. Dr Peter Pentz of the Department of Prehistory at the National Museum of Denmark writes:

Its size, the amount of timber used and manpower involved indicate that the bridge was built by the major power of that time. As it is closely contemporary with the Viking Age geometric ring fortresses in Denmark, it is natural to interpret the Ravning bridge […] as an important part of the political and military activity around the year 980.

Again, could the bridge at Kinloss have been a causewayed section of a similar 10th-century military route between Forres and the probable royal centre at Burghead?

It is worth noting that according to Wikipedia (with no citations), archaeologists have also suggested that the Ravning Bridge may have functioned as a jetty and trading point for the mooring of ships.

Given the proximity of Kinloss to the natural harbour of Findhorn Bay, the idea that the ‘bridge’ could have been a jetty – as suggested to me by Helen McKay of the Pictish Symbols: Art and Context group on Facebook – should probably not be ruled out either.

What have I learned?

Research for this blog has proved me wrong on three counts:

My first assumption – that there couldn’t have been a bridge as early as 966 AD because bridges didn’t exist in north-east Scotland then – has proved to be false.

My second assumption – that there was no water-course at Kinloss in 966 AD to warrant a bridge – is also rocky, because the waterscape in the area has changed so much.

My third assumption – that mention of a bridge at Kinloss is anachronistic, because there was no settlement at Kinloss prior to the foundation of the Abbey – is questionable, because the bridge could have been part of a routeway through marshy countryside, possibly between Forres and Burghead.

I will say that if there was a bridge at Kinloss in 966, it must not have survived long, as there’s no mention of a bridge – or any bridge maintenance obligation – in any of the 12th-century grants of land to Kinloss Abbey.

Could it have become surplus to requirements after Burghead was destroyed, sometime between 930 and 980 AD? If no one was obliged to maintain it, it would soon have rotted or collapsed. By the time the abbey was founded 200 years later, there would have been no trace of it.

In the absence of archaeological evidence, we’ll probably never know for sure. But I am more inclined to believe it existed now than I was when I started!

References

G.W.S. Barrow, Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000-1306

M. Carver et al, Portmahomack on Tarbat Ness (2019)

C. Clerk, Burghead, Moray: A history of archaeological thought (2019)

D. Harrison, The Bridges of Medieval England (2004)

I. Henderson and G. Henderson, The Art of the Picts (2004)

History Hit Gone Medieval podcast, Alfred the Great with Dr Cat Jarman and Justin Pollard (2022)

B. Jones and I. Keillar, In Fines Borestorum: Reconstructing the Archaeological Landscapes of Prehistoric and Proto-Historic Moray (1986)

N. McGuigan, Máel Coluim III ‘Canmore’: An Eleventh Century Scottish King (2021)

C. Mount, Were there bridges in medieval Ireland?

People of Medieval Scotland (POMS) Database

A. Ross, Land Assessment and Lordship in Medieval Northern Scotland (2015)

M. Stratigos and G. Noble, Crannogs, castles and lordly residences: new research and dating of crannogs in north-east Scotland (2015)

J. Stuart, Records of the Monastery of Kinloss with Illustrative Documents (1872)

A. Taylor, The Shape of the State in Medieval Scotland 1124-1290 (2016)

University of Memphis Department of Civil Engineering, Clonmacnoise Bridge by Aidan O’Sullivan and Donal Boland

If you want to pursue the bridge = causway idea, then have a look at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jarlabanke_Runestones

(From memory - Bridge-building is mentioned on runestones as a pious act as it enabled parishoners to traverse water/boggy ground to attend church)