The meaning of ‘carden’ in Pictish place-names

In which I suggest a link between ‘carden’ names and early medieval hunting grounds

Place-names are some of the best evidence we have that the Picts of early medieval (c. 400–900 AD) eastern Scotland spoke a Brittonic Celtic language similar to Old Welsh.

Names like Aberdeen, Perth, Keith and Kincardine are often cited to show that the Picts used Brittonic words like aber (river mouth or confluence), pert (wood), coed (also wood) and cardden (currently generally understood as ‘thicket’) when naming the places around them.

It’s the last of these, cardden, that I want to look at for this blog. It appears in many Pictish and hybrid Pictish-Gaelic place-names as carden, but its meaning is currently disputed, with some scholars favouring an interpretation of ‘thicket’ and others arguing for a meaning of ‘fort’ or ‘enclosure.’

I want to propose a different interpretation: that carden in Pictish and hybrid Pictish-Gaelic place-names specifically meant a hunting reserve, and perhaps a royal hunting reserve.

But first, a caveat

Before I start, a caveat. I’m not a Celtic linguist, still less a Celtic historical linguist, so the argument I’m going to put forward isn’t based on any kind of linguistic analysis.

Instead, it’s based on an analysis of the landscapes around places that have ‘carden’ in their names, along with other things that are known or can be observed about those places.

An eighth-century ‘royal place’ at Kincardine, Easter Ross

The first thing to note is that I wouldn’t have gone down this rabbit hole at all if it hadn’t been for a comment by Alastair Fraser on my recent blog about ‘David’ sculpture in Moray and Ross.

There, I’d argued that one of the places 8th-century kings of Moray used to visit on their tours of the kingdom was Kincardine, on the southern shore of the Dornoch Firth near Bonar Bridge.

That’s because Kincardine parish church has a fine 8th-century grave-slab with carvings of the biblical King David and a lone armed horseman—both emblems of Pictish kingship.

There are also David-themed carvings at Nigg, Kinneddar and (perhaps) Hilton of Cadboll. Building on a recent talk by Professor Jane Geddes about David imagery in Pictland, I suggested that these were all stops on a royal circuit of the early medieval kingdom of Moray.

However, stops on a royal circuit were usually wealthy secular or monastic estates where the king and his retinue could stay for a few weeks being fed and entertained. I couldn’t see how Kincardine might be a wealthy estate, as it has little fertile land in its vicinity. But I did mention in passing that the highland hinterland of Kincardine seemed suited to hunting.

Kincardine as a hunting place?

I was only thinking about the sculpture at that point, so I hadn’t considered the place-name at all. However, Alastair commented:

Remember Kincardine, or at least the carden element, is also a Pictish word, meaning woodland. So maybe a king would visit to go hunting at the “head of the woods.” If its primary purpose was for the hunt there would not necessarily need to be an estate to provide sustenance for a longer stay.

A spot-on insight (as ever), and it reminded me that there has been much debate in academic circles over the meaning of ‘carden’.

Although it was indeed once thought to mean ‘woodland’ or ‘thicket,’ these interpretations were challenged in 1999 by the philologist Professor Andrew Breeze.

Breeze looked at the handful of medieval Welsh literary texts and place-names that use the word cardden, and argued that it makes more sense if it’s understood as a fort or enclosure. Hence, he argued, a presumed Pictish carden must mean ‘fort’ rather than ‘woodland.’

26 years of academic debate

This sparked a long-running debate among linguists and place-name specialists—including my own PhD co-supervisor Professor Thomas Clancy, who looked at carden in a 2017 article on the etymologies of Pluscarden and Stirling.

He recapped the debate, highlighting the contribution of Dr Alan G. James, a Brittonic place-name specialist. For his Brittonic Language in the Old North: A Guide to the Place-Name Evidence, Alan had also gone back to the medieval Welsh texts, and pronounced that:

An impartial reading of the citations in [the online Welsh dictionary] GPC suggests that a cardden is somewhere difficult to get into or through. A meaning like ‘an enclosure surrounded by a thick hedge’ would seem reasonable.

While endorsing Alan’s view, Thomas noted that any further progress would probably have to come from looking at ‘carden’ places, rather than endlessly examining the Welsh sources:

Whatever the meaning of the poorly-attested and -understood Welsh word, we do not know the semantics of its Northern Brittonic or Pictish cognate(s), and perhaps we would be better to try to derive a meaning from a survey of the topography related to these names.

Alastair’s comment and Thomas’s article gave me two lines of enquiry to follow. Firstly, could carden names in Pictland refer to hunting forest, as Alastair had suggested, and secondly, could an examination of their topography, as recommended by Thomas, provide further clues?

Hunting as a Pictish royal sport

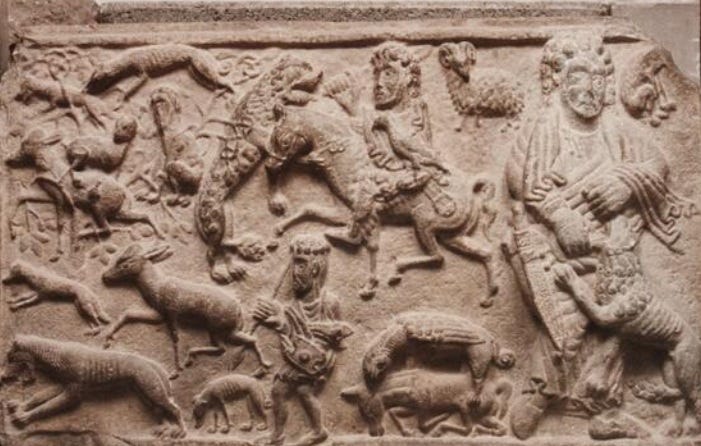

There’s no doubt that Pictish elites liked to hunt. Hunting with hounds (and occasionally hawks) is a very common theme on Pictish sculpture. In the Moray Firthlands it appears on three of the four ‘David’ monuments noted above (the fourth is a fragment, so it may also have had a hunt scene), on cross-slabs at Shandwick and Elgin, and on a shrine fragment from Burghead.

Even if these scenes are allegorical, the overall impression is that hunting was something Pictish kings and nobles did a lot. The social importance of hunting in the early Middle Ages has been well studied for other, better-documented European societies, so this is hardly surprising.

However, because there are so few written records for early medieval Scotland, Pictish hunting grounds are almost completely unresearched.

A clue from Kincardineshire

Looking for anything that might have been written on the subject, I came across a 2013 article by Kevin Malloy, Derek Hall and Richard Oram called Prestigious landscapes: an archaeological and historical examination of the role of deer at three medieval Scottish parks.

I’d barely got past the title when I realised that one of the deer parks they’d looked at was Kincardine Park in Kincardineshire (in the council region of Aberdeenshire). The authors noted that:

While documentary evidence is silent on the use of Kincardine Park as a hunting ground, it seems likely… that royal hunts were performed there. Historical sources provide evidence that the kings of Scotland utilized this park for centuries, possibly as early as the reign of William the Lion in the second half of the twelfth century. William spent a great deal of time at nearby Kincardine Castle and is acknowledged as one of the first park builders in Scotland.

Here was another clear link between carden, hunting and royalty—even if the king in question belonged to the twelfth century rather than the eighth.

What’s more, the article argued that medieval deer parks were enclosed, showing that Kincardine Park was enclosed by a stone wall, perhaps with a wooden pale on top. Here was a possible link between carden and Andrew Breeze’s proposed meaning of ‘enclosure’, modified by Alan James to ‘enclosure surrounded by a thick hedge’.

However, the authors saw the enclosure of deer parks as a twelfth-century innovation, writing:

It is possible that William’s grandfather, David I (r. AD 1124-1153), first introduced parks to Scotland. He was raised largely in England, where parks already existed, and certainly introduced Anglo-Norman colonists, and their culture more generally, to Scotland during his years on the throne.

So without more evidence, it would be problematic for me to suggest that enclosed deer parks or hunting reserves were a feature of Pictland, centuries before David I ascended the throne.

A royal hunting ground at Pluscarden, Moray?

Undeterred, I went back to look at Thomas’s article about Pluscarden, near Elgin. Today, this is well known as the site of a Valliscaulian abbey founded by Alexander II in the thirteenth century.

However, as carden is a Pictish word, mentioned as early as 700 in Adomnán’s Life of Columba, the place-name must be older even than the tenth century, when Pictish is thought to have been eclipsed by Gaelic as the dominant language in Moray.

In fact, Thomas pointed out that the place-name didn’t originally refer to the abbey itself, but to the forest in which it was built, thus pre-dating the abbey:

In the earliest original charter relating to [the abbey] (of 1233), it is described as being founded in foresta de Ploschardin, and it is reasonable to assume that it was originally a topographical name, as was the case with many monastic foundations in Scotland, both early and medieval.

In his article, Thomas focused mostly on the first part of the name—the strange and rarely-attested plusc—rather than the carden element. He identified it as a possible Gaelic plaosg, meaning eggshell or nutshell, and surmised that:

…the association is with nuts, or nutshells, perhaps a location abounding in nutshells, because animals (including domesticated animals such as pigs) frequent the woods to eat easily-peeled nuts.

This, he said, threw the carden element into doubt, firstly because plaosg is Gaelic not Pictish, and secondly because the name Pluscarden only has one ‘c’ in the middle, which Thomas saw as belonging to plusc/plaosg. An alternative reading, he wrote, would be plusc-ardin, where ardin could be from Gaelic àrd for ‘height,’ referring to Heldon Hill behind the abbey.

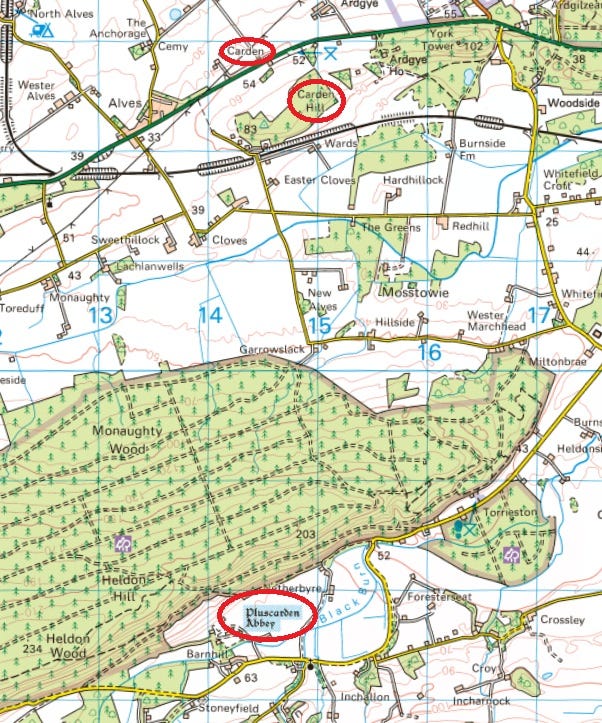

However, he wasn’t convinced of this, firstly because it wouldn’t explain the persistent use of -en rather than -in (or -ie) at the end of the name, and secondly—and crucially for this blog—because of the existence of two other place-names not far away from Pluscarden.

Strengthening the potential for carden to be the second element, Peter McNiven has noted… the presence of a place-name Carden, as well as Carden Hill nearby (NJ 140 627; it is Cardon on Roy’s map, so is at least as old as the 1750s).

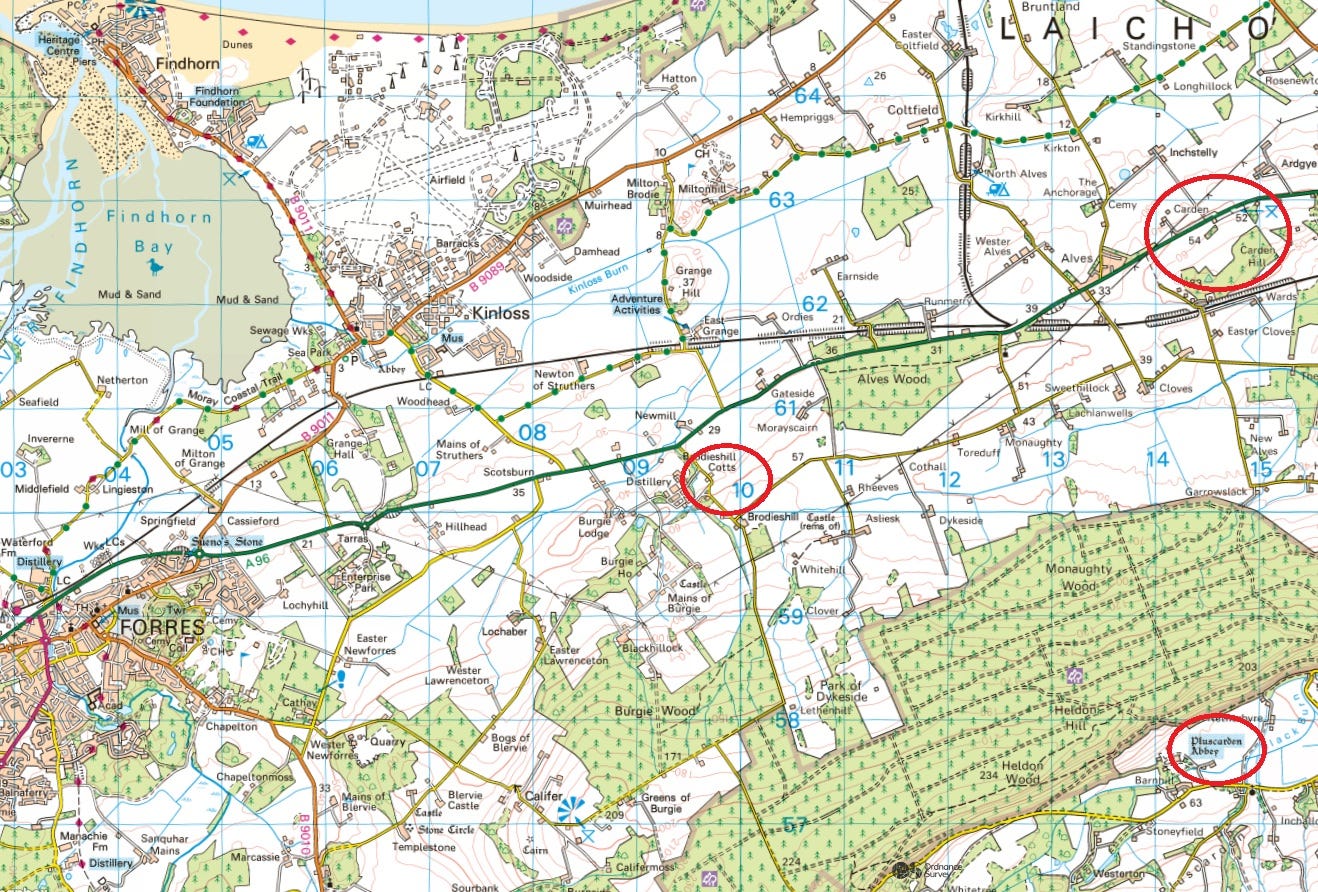

And indeed, Peter was correct—these two names appear either side of the A96 Inverness to Aberdeen road, about four miles due north of Pluscarden:

Fort, forest or hunting reserve?

The first thing to note here is that these names throw the interpretation of carden as ‘fort’ into serious doubt. There’s no known early medieval fort anywhere nearby, and in any case these names are four miles apart. If they all refer to the same feature—and my argument is that they do—then that feature must have spread over quite a wide area.

Then there’s the reference in the earliest charter of Pluscarden, from 1233, to the abbey being founded in foresta de Ploschardin.

Foresta looks like our word ‘forest,’ but in the Middle Ages, different types of woodland had different uses, which were reflected in different Latin words. In a 2016 article on woodland management in medieval Scotland, for example, Dr John Gilbert noted that:

The three most common Latin words for woods, boscus, nemus and silva, can all be quite correctly translated as wood or woodland, but… these words contain more specific meanings. Nemus usually meant a larger wooded area as did silva, but on occasions they were used to mean a smaller wood. Boscus on the other hand usually meant a smaller wood, coppice or underwood – though it could be used to mean a larger wood.

While that isn’t necessarily as clear-cut as one might like, it does show that woodland words weren’t just used willy-nilly. Pluscarden wasn’t founded in a boscus, nemus or silva, but a foresta. So what might this mean? Strangely, Dr Gilbert didn’t offer a meaning for it, even though he later mentioned (without comment) examples of foresta in medieval Scottish charters.

But in a 2004 article by the environmental historian Professor Dolly Jørgensen, on multi-use management of the medieval Anglo-Norman forest, we get an insight into what the term meant in Norman England:

Although royal hunting grounds existed in England prior to the conquest, William the Conqueror imported the term ‘forest’ and its legal implications from the Continent. ‘Forest’ most often designated a legal entity consisting of extensive land, including both woodland and pasture, within which the right of hunting was reserved for the king or his designees and was subject to a special code of laws administered by local officials.

So to the Anglo-Norman aristocracy—among whom we might count Alexander II of Scots—foresta specifically meant land (not necessarily woodland) in which the king had hunting rights.

Here again, we get a hint that carden places were related to hunting grounds. This might also explain the four-mile distance between Pluscarden on the south side of Heldon Hill and Carden on its north side: did they lie on either side of a hunting reserve?

More evidence from Moray

I’ve been trying to reconstruct the early medieval landscape of Moray since I started writing this Substack in 2022, so I have a few more things to add into the mix here.

Firstly, in a charter of Richard de Lincoln, bishop of Moray, dated sometime between 1187 and 1214, we learn that William the Lion granted to Kinloss Abbey:

…all of the land of Burgie that is on the north side of the via regia which goes from Forres to Elgin, that is from the stream in the west as it exits the nemus, to the great silva of Kilbuiack… [my translation from Latin]

Here, we should recall that both nemus and silva meant ‘a larger wooded area.’ As the twelfth-century via regia between Forres and Elgin followed roughly the same route as the modern A96, the “great silva of Kilbuiack” looks very much like it might have formed part of the foresta in which the abbey of Pluscarden was founded.

In fact, a look at the Ordnance Survey map (below) is enough to appreciate that the modern-day woods of Burgie, Alves, Carden Hill, Monaughty and Heldon could all once have been part of a single expanse of hilly foresta in which medieval kings reserved the right to hunt.

The foundation legend of Kinloss Abbey may add further weight to the idea that this was a royal hunting ground. It recounts that David I was hunting nearby when he became lost in a dense wood. Finding his way to a clearing where he was looked after by some shepherds, he pledged to found an abbey on that very spot.

Though these are highly unlikely to be the factual circumstances of the abbey’s foundation, the idea that the king might have been hunting in the nearby woods was presumably plausible.

The well of the Fianna

Even more satisfyingly—and I’m very grateful to my supervisor Professor Katherine Forsyth for jogging my memory about this—there is a lost place-name within the great silva of Kilbuiack that offers further evidence of this area’s use for medieval hunting.

The name appears in a charter of Alexander II from 1221, detailing a grant to Kinloss Abbey of a plot of land that I’ve previously narrowed down to a location in or around Kilbuiack.

The boundaries of the plot are described as follows:

From the great oak tree in Malevin... to the Rune Pictorum, and from there to Tubernacrumkel, and from there along the ditch to Tubernafein, and from there to Runetwethel, and from there along the burn that runs through the marsh to the ford that is called Blackford, which is between Burgie and Ulern. [My translation from Latin]

The relevant place-name here is Tubernafein, which, with the help of various specialists back in October 2023, I established means ‘well of the Fianna’.

The Fianna are the folkloric companions of Fionn mac Cumhaill (Finn McCool), who appear in medieval Gaelic literature as a band of wild hunter-warriors.

Research by Professor Elizabeth FitzPatrick has shown that in Ireland, place-names associated with Fionn and the Fianna are indicative of hunting grounds. In a 2012 article on another Fionn-related place-name element, formaoil, she wrote that:

[D]esignated hunting preserves of kingdoms may have been the habitat of the early historic fian in Ireland. Where those hunting preserves are, is perhaps intimated by formaoil landscapes, whether indicated by place-names that embrace that term, such as Formoyle on the north shore of Lough Gill (Co. Sligo), or by places that have comparable topographies and are distinguished by later deer parks and by monument names referring to Fionn Mac Cumhaill and his fian.

So in Pluscarden, Carden and Tubernafein we have strong hints of a hunting reserve in the hilly ground between Elgin and Forres that seems to have endured from Pictish times (pre-900 AD), through Gaelic times (c.900–1150), and into the documented twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Mapping carden names across Scotland

So far I’ve been able to link two Kincardines, Pluscarden and Carden to hunting without much difficulty, but what about the other carden places?

Before I started looking into this, my impression was that there are only a few such place-names in the part of Scotland that was once Pictland. But it turns out there are a lot!

There are seven Kincardines, for a start, and quite a few Urquharts, which we know from Adomnán’s Life of St Columba were originally called Airchartdan. A lot of places that have cairnie in their name can also be traced back to carden.

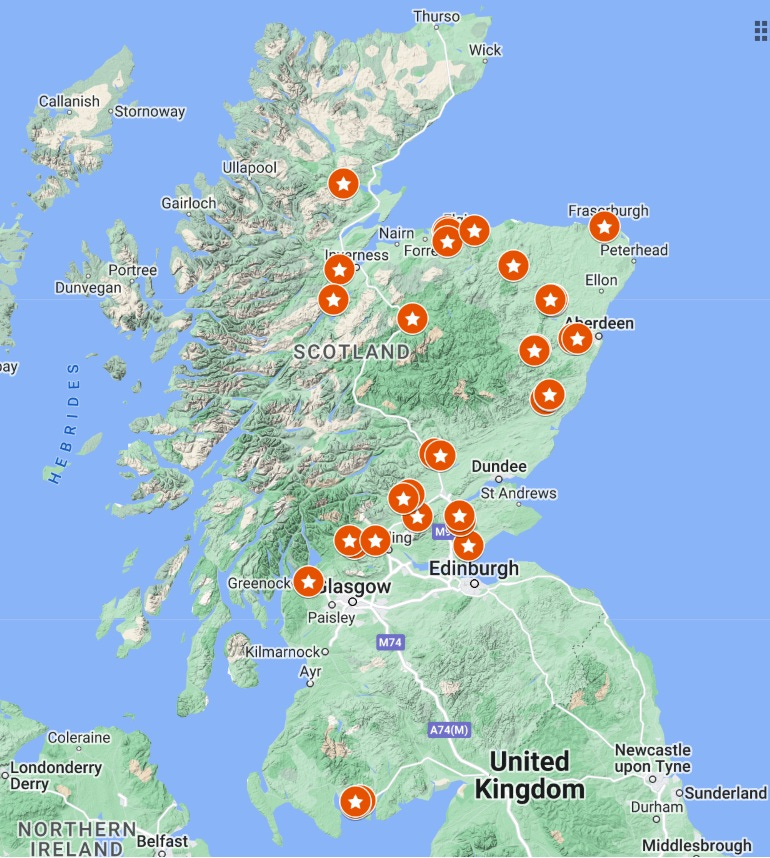

So far I’ve gathered 39 carden names, drawing from examples cited by place-name specialists including W.J. Watson, W.F.H. Nicolaisen, Alan James, Thomas Clancy, Peter McNiven and Simon Taylor, and plotted them on an interactive map .

While I haven’t investigated them all in detail—that would probably be a PhD in itself!—a few things are immediately notable.

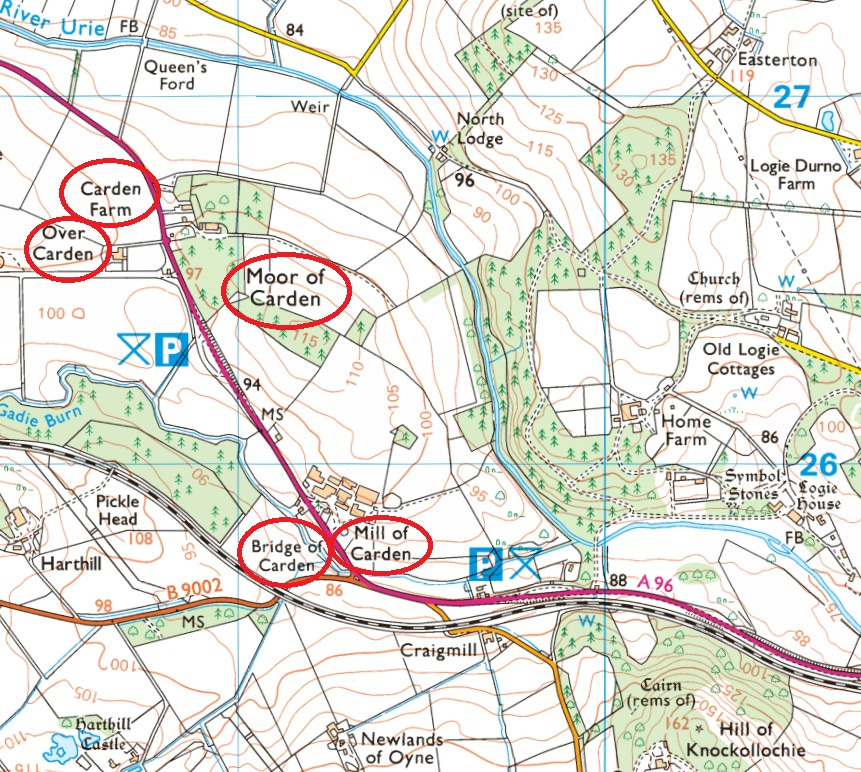

Firstly, as with Pluscarden, Carden and Carden Hill, they tend to appear in clusters over a broad area. Here in the Garioch in Aberdeenshire, for example, we have five carden names spread out along a stretch of hillside:

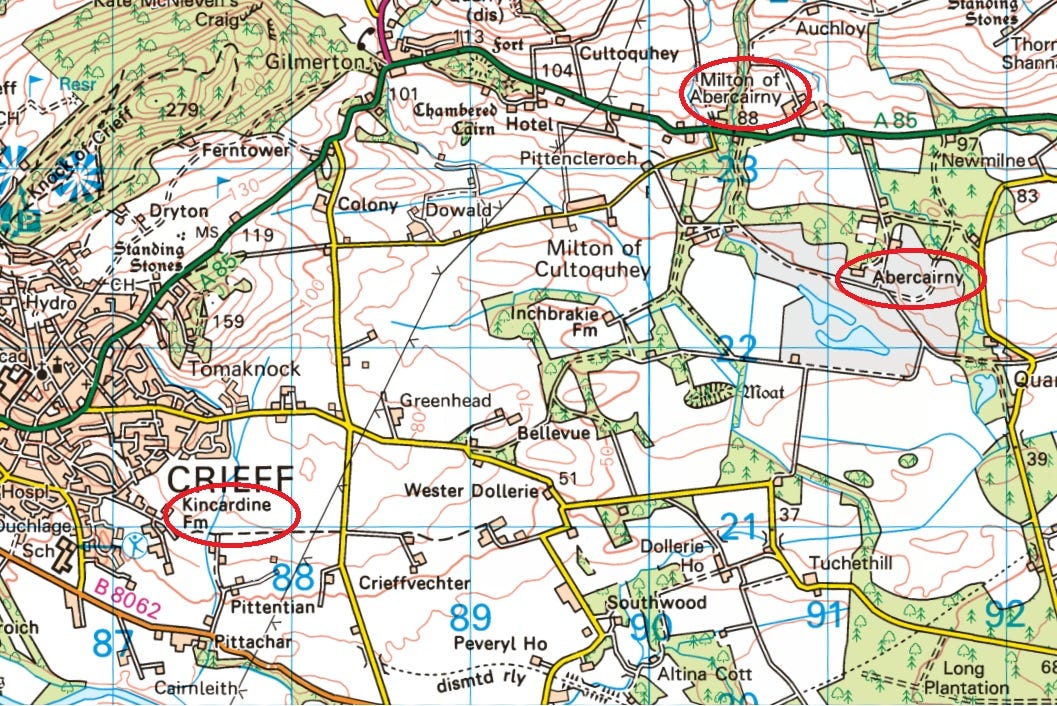

And here at Crieff there is a Kincardine Farm with two Abercairny names on the high ground:

Carden and Elrick

Secondly, carden names often co-locate with other place-names that can be more certainly linked to hunting.

I’ve already mentioned one type of hunting place-name: names associated with Fionn and the Fianna. Another common hunting place-name is Elrick or Elrig – a Gaelic word for a kind of deer trap. Elricks were walls built to funnel deer off the hillsides into a small area where the poor creatures could be shot at by medieval hunters. (I don’t like to think about this too closely.)

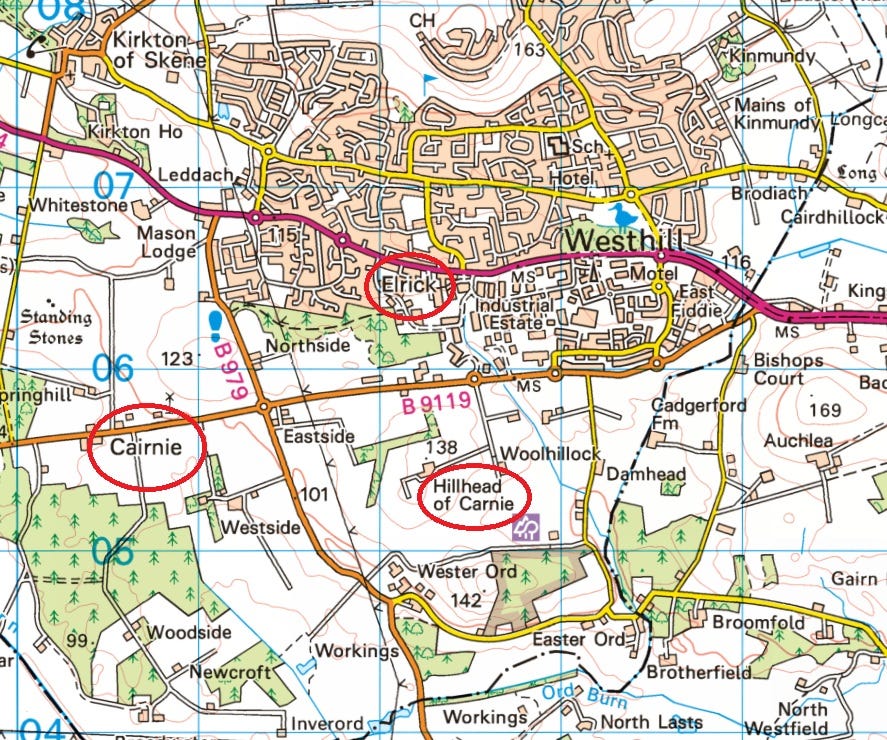

Here at Westhill in Aberdeenshire, for example, we have two carden names—Cairnie and Hillhead of Carnie—close to an Elrick.

Carden and Eileag

In a 1913 article for the Celtic Review entitled Aoibhinn an Obair an t-Sealg, the toponymist W.J. Watson noted that in the far north of Scotland, an elrick was known by the related word eileag. He related this tale from Kincardine parish in Easter Ross:

[In] the old times the people of Strathcarron were often hard pressed by the Lochlannaich [Norsemen]... At such times, two places were of great importance, Cairidh Cinn-Chàrdain the weir of Kincardine, near the parish church, for the catching of salmon, and Eileag Bad Challaidh in the heights, for deer.

In this folk-memory from the nineteenth century, we can see a glimpse of what might have attracted eighth-century Pictish kings to Kincardine: plentiful salmon in the fish trap (perhaps this one, or an ancestor of it), and plentiful deer in the uplands. While Eileag bad Challaidh is no longer on any map, a relationship between eileag and carden is explicit in the tale.

Cartenan, St Andrews and the Boar’s Raik

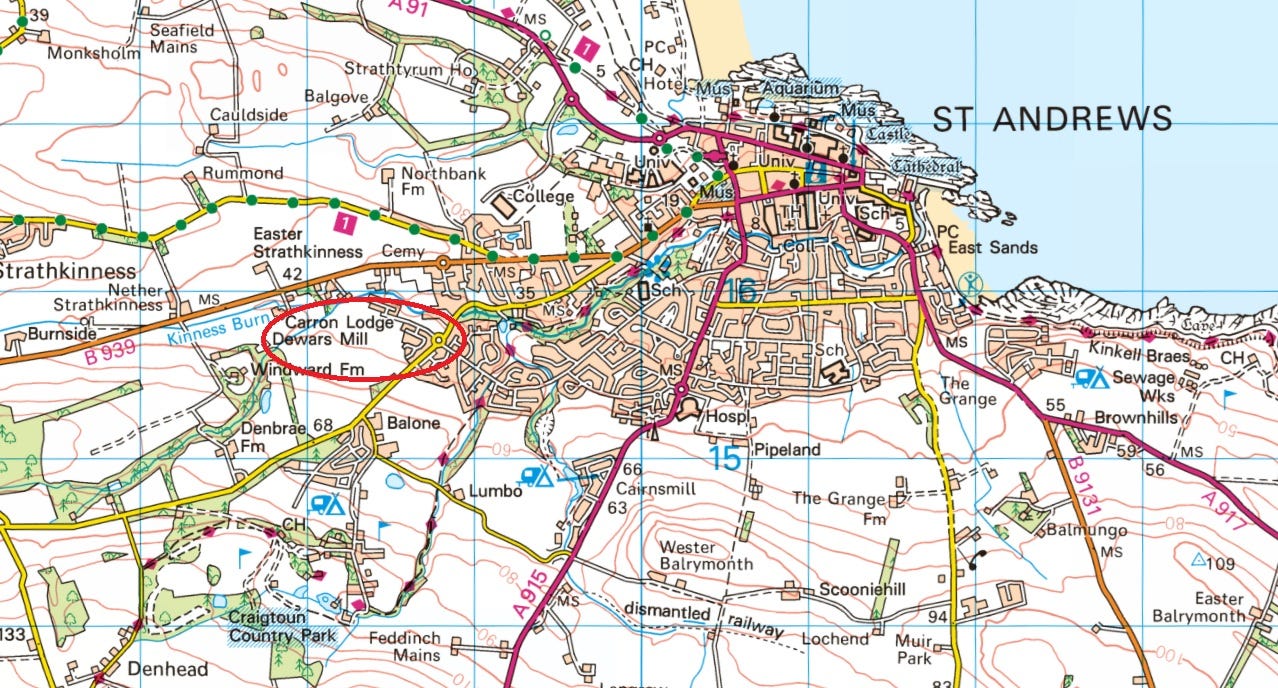

One last example (for this blog) relates to St Andrews, or as it was known in Gaelic, Cennrígmonaid—the ‘head’ or ‘end’ of the ‘king’s muir.’

Jane Geddes reminded me that in early charters to the monastery, a large tract of land in the hinterland of St Andrews went by the name of ‘The Boar’s Raik’—a possible reference to boar hunting.

If Kincardine in Easter Ross was a place where eighth-century kings went to hunt, could Cennrígmonaid have had something of the same meaning? Like Kincardine, it also has an eighth-century burial monument with David and hunt imagery—the famous St Andrews Sarcophagus.

While mulling this, I read Simon Taylor’s chapter on early place-names around St Andrews in the 2017 book Medieval St Andrews: Church, Cult, City. It included this interesting excerpt from the ‘A’ version of the St Andrews foundation legend:

Thereupon [Regulus] came [from Constantinople, with St Andrew’s relics] with an angel attending and guarding his way, [and] he arrived successfully at the top of the king’s hill, that is Rithmonut. The same hour in which he had encamped there, tired, with his seven companions, a divine light shone around [King Ungus] of the Picts who was coming with his army to a special place which is called Cartenan.

Of this place-name Cartenan, Simon commented:

It is not clear where Cartenan might be. However, given the strong focus on St Andrews itself in the second part of FAA, it is likely to be in the immediate environs. It is just possible that it is an early form of Carron, a small settlement that lay on the old main route from the south-west, within about 3km of St Andrews Cathedral.

If Simon is correct, this may be another instance of a carden name at the edge of another royal hunting ground: the Boar’s Raik.

Conclusion: links with hunting – but what about enclosure?

I started this investigation with a vague idea that the carden of Kincardine in Easter Ross might relate to hunting, and that this is what made it a destination on my proposed eighth-century royal circuit of the kingdom of Moray.

The more I’ve looked into it, the stronger the link has become. Carden places seem to mark relatively wide areas of upland, are often co-located with other hunting-related place-names, and some of them maintain traditions of hunting down to modern times.

There is no obvious connection to a fort in any example I’ve looked at, and I would personally rule that interpretation out.

While I can’t say whether Pictish hunting reserves were enclosed, I wouldn’t like to discount it. The medieval Welsh examples of cardden seem to have a connotation of an ‘enclosed place,’ so it’s definitely worth bearing in mind. However, this is the kind of thing that can only really be proved through archaeology, so perhaps an answer won’t be forthcoming any time soon.

If you have any thoughts on the enclosure aspect, or on anything else I’ve covered here, I’d be delighted to hear them!

References

Breeze, Andrew. 'Some Celtic Place-Names of Scotland, including Dalriada, Kincarden, Abercorn, Coldingham, and Girvan,’ Scottish Language (18): 34–51.

Clancy, Thomas. ‘The etymologies of Pluscarden and Stirling.’ Journal of Scottish Name Studies 11 (2017): 1–20.

Cowan, Ian B. The Parishes of Medieval Scotland (1967)

FitzPatrick, Elizabeth. ‘Formaoil na Fiann: Hunting Preserves and Assembly Places in Gaelic Ireland.’ Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium (2013): 95–118.

Gilbert, John M. ‘Woodland management in medieval Scotland.’ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 146 (2016): 215–252.

James, Alan G. The Brittonic Language in the Old North: A Guide to the Place-Name Evidence. (2019).

Jørgensen, Dolly. ‘Multi-use management of the medieval Anglo-Norman forest.’ Journal of the Oxford University History Society 2 (2004): 1–16.

Malloy, Kevin, Derek Hall and Richard Oram. ‘Prestigious Landscapes: An Archaeological and Historical Examination of the Role of Deer at Three Medieval Scottish Parks.’ Eolas: The Journal of the American Society of Irish Medieval Studies 6 (2013): 68–87.

McNiven, Peter. ‘Gaelic place-names and the social history of Gaelic speakers in medieval Menteith.’ PhD thesis, University of Glasgow (2011)

Nicolaisen, W.F.H. Scottish Place-Names (1976)

Stuart, John (ed.) Records of the Monastery of Kinloss with Illustrated Documents (1872)

Taylor, Simon. ‘Pictish place-names revisited.’ In Pictish Progress: New Studies on Northern Britain in the Early Middle Ages. Brill, 2011.

Taylor, Simon. ‘From Cinrigh Monai to Civitas Sancti Andree: A Star is Born.’ In Medieval St Andrews: Church, Cult, City, edited by Michael H Brown and Katie Stevenson. Boydell and Brewer, 2017: 20–34.

Watson, W.J. ‘Aoibhinn an Obair an t-Sealg.’ The Celtic Review 9:34 (November 1913): 156–68.

Watson, W.J. The History of the Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (1926)

As always excellent, thought provoking and very useful. Inevitably I started thinking about Stirling, here we have a David I Royal wood (called a nemus on the burgh seal) then a park founded by William the lion. We have Gart names both sides of the Forth and a Kincardine to the north, 'head of the wood' (Gaelic and Pictish....Peter McNiven's excellent phd), next to a lovely motte. Is this perhaps the entry to to the woods from the Alba end? Kincardine parish runs to the Forth and Dunblane with its 9th/10th century cross is up the road. Can't find any Elrick placenames as yet but we certainly have one on the ground in the park!

Bravo!

Great read. Thanks! Happy to do a PhD as suggested.

Would just like to add to the Crieff Kincardine and cairnie - over by Auchterarder there is a Kincardine Glen, very enclosed with the Water of Ruthven running through its length, and Kincardine Castle (rebuilt to the east of the original and situated atop the glen). There is also the cairnie brae (A9 where lorries get stuck of snowing), on the way to Perth.