What can the Pillar of Eliseg tell us about Sueno's Stone?

In which I think about analysing Sueno's Stone using techniques applied with great success to the ninth-century Pillar of Eliseg in north Wales

Apologies to long-time subscribers that I haven’t posted for a while – I’ve been sidetracked writing essays for my MA and getting stuck into a chunky new module on Historical Methods, not to mention doing actual bill-paying client work.

And a big welcome to new subscribers! This blog is getting more niche by the day, but if you like long posts that dig about in obscure aspects of the early medieval history and archaeology of Moray in Scotland, you’ve definitely come to the right place.

Unpacking Sueno’s Stone: the story so far

I’m getting closer to starting my MA dissertation, so I’m planning to use this and the next few posts to test out some of the approaches I might take to it.

All along, I’ve known I wanted to focus on Sueno’s Stone near Forres, ideally to try to answer the questions that historians, archaeologists and amateur antiquarians have been wrestling with for the past 250 years at least: when was it put up, who by, what for, and why in Forres?

Reading the literature, it’s become clear to me that traditional methods of tackling these types of questions about early medieval carved stones haven’t really got us very far.

The big three methodological approaches, as previously explored in this post, are:

Dating on art-historical grounds: What kind of art style and iconography are used on the stone, and can they be compared with other stones whose date is known?

Dating on historical grounds: Do the battle scenes on the reverse face of the stone relate to a real, documented, historical battle whose date we know?

Dating on scientific evidence: Can the stone be dated by applying carbon-14 dating techniques to organic material removed from post-holes found around it?

All three methods have been applied to Sueno’s Stone, and the result, mostly from the art-historical analysis, is a tentative consensus that the stone was raised in the period 850-950 AD (although the C14 dating tells a less clear-cut story, throwing up dates ranging from the fourth to the twelfth century AD).

But while that gives us a rough time period for the stone’s appearance in the landscape, we’re not really any the wiser as to who put it up, what for, or why here on the eastern edge of Forres.

With these three approaches near-exhausted—although excitingly I think there’s some more C14 evidence to come—are there any other ways we can try to get at the historical context of the stone?

In fact I think there are quite a few, and I’m excited to try them out. For this blog I just want to talk about one: looking at the stone’s setting in the immediate and wider landscape.

Inspiration from the Pillar of Eliseg in Wales

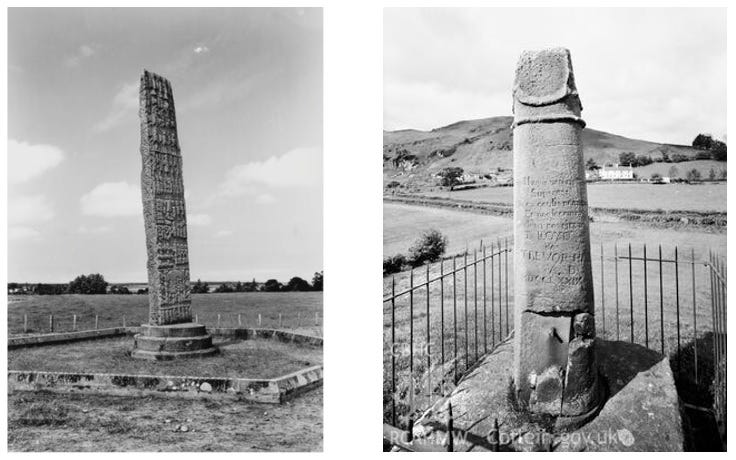

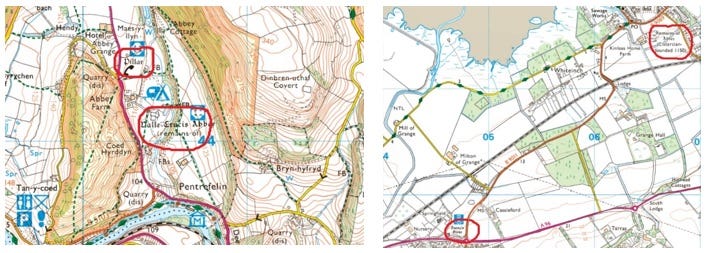

In this I’ve been inspired by some excellent and very thorough work carried out 10-15 years ago on another early medieval monument, and one I keep coming back to in my mind because it seems to have so many parallels with Sueno’s Stone: the Pillar of Eliseg in Denbighshire in north Wales.

Here are some parallels I think are notable:

Like Sueno’s Stone, the Pillar of Eliseg is still in—or rather, has been returned to—its original position, standing in the middle of the valley of Nant Eglywseg about 3.4 km northwest of Llangollen.

Like Sueno’s Stone it is (or was) a tall, solitary monument, probably around 4m tall originally (Sueno’s Stone is 6.5m), but elevated further by its position on top of a Bronze Age burial mound.

Like Sueno’s Stone it once had a cross, although the pillar was broken in half sometime in the seventeenth century and the stone cross which almost certainly topped it has disappeared.

Like Sueno’s Stone, the Pillar of Eliseg is not associated with any known early medieval settlement or ecclesiastical site, but rather stands alone in a highly strategic location (more of this in a bit).

The two monuments are also near-contemporaries. The Pillar of Eliseg can be dated with a high degree of certainty to 820–850 AD, while Sueno’s Stone has been given a date range of 850-950 AD, with the latest thinking nudging it towards the earlier part of that period.

Finally, and fascinatingly to me, both monuments are also located close to a ruined Cistercian abbey. The Pillar of Eliseg is just 400m from Valle Crucis Abbey, founded in 1201 by Prince Madog ap Gruffydd of Powys Fadog. And although few historians or archaeologists have linked these two sites,1 Sueno’s Stone is just 3.5 km from Kinloss Abbey, founded in 1150 by David I of Scotland.

Interpreting the Pillar of Eliseg

But unlike Sueno’s Stone, we know an awful lot about the Pillar of Eliseg—thanks mainly to some outstanding research carried out between 2009 and 2017 by archaeologists from Bangor and Chester universities, led by Professor Nancy Edwards at Bangor and Professor Howard Williams at Chester.

They’ve used a barrage of methods, both traditional and novel, to try to extract more information from the pillar about its original purpose and function(s). And the information they’ve managed to extract makes me very optimistic that a similar multi-faceted approach to Sueno’s Stone could help to tease out its original purpose and function(s) too.

The research kicked off in 2009 when Edwards published a paper in Antiquaries Journal called Rethinking the Pillar of Eliseg. She took as her starting point the most contentious aspect of the pillar: a very long inscription that has long worn away, but which had been transcribed in 1696 by the antiquarian Edward Lhuyd.

Historians had previously thought this transcription to be suspect, but Edwards had found a second transcription that closely matched it, suggesting it was indeed a faithful reproduction of the original.

It turns out to be an inscription in Latin, apparently carved at the time of the pillar’s creation, and it provides an extraordinary amount of detail about who raised the pillar and why, and the historical context in which it was set up.

The inscription—or what was left of it when Lhuyd transcribed it—reads as follows:

+ CONCENN FILIUS CATTELL CATTELL

FILIUS BROHCMAIL BROHCMAL FILIUS

ELISEG ELISEG FILIUS GUOILLAUC

+ CONCENN ITAQUE PRONEPOS ELISEG

EDIFICAUIT HUNC LAPIDEM PROAUO

SUO ELISEG + IPSE EST ELISEG QUI NECR

XIT HEREDITATEM POUOS - -IPC- - MORT

CAVTEM PER UIM - - E POTESTATEANGLO

- - - - - - - - - - IN GLADIO SUO PARTA IN IGNE

- - - - - - - - - - - - - .MQUE RECITUERIT MANESCR-P

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - .M DET BENEDICTIONEM SUPE

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - . ELISEG + IPSE EST CONCENN

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - TU.–.C- -E MEIUNGC–MANU

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - EAD REGNUM SUUM POUOS

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - .EyIUBAUI-S-ET QUOD

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - y.S.AIS-UCAUES.E

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - ..R-EIN- -MONTEM

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - y - - . -. MONARCHIAM

- - - - - - - - - - - AIL MAXIMUS BRITTANNIAE

- - - - - - - - NN PASCEN - - MAU.ANNAN

- - - - - - BRITUA-T-M FILIUS GUARTHI

- - - - - - QUE BENED – GERMANUS QUE

- - - -.PEPERIT EISE-IRA FILIA MAXIMI

- - - GIS QUI OCCIDIT REGEM ROMANO

RUM CONMARCH PINXIT HOC

CHIROGRAFU REGE SUO POSCENTE

CONCENN _ BENEDICTIO DNI IN CON

CENN ET S. I TOTA FAMILIA EIUS ET IN TOTA RAGIONE POUOIS

USQUE IN - - - - - -

If you know any Latin, you can probably already see that there is some exceptionally useful and interesting information here.

Almost the first thing we learn is that the stone was raised by Cyngen (Concenn), a known historical figure who was king of Powys from 808 AD until his death in Rome in 854/855:

Concenn pronepos Eliseg edificauit hunc lapidem pro avo suo Eliseg

Cyngen great-grandson of Eliseg constructed this stone in honour of his ancestor Eliseg

And towards the end we even learn who was responsible for writing the inscription:

Conmarch pinxit hoc chirografu[m] rege sui poscente Concenn

Conmarch painted this text at the order of his king, Cyngen

In between there is a long, epic diatribe that links Cyngen and his great-grandfather Eliseg to the rise and subsequent fortunes of the kingdom of Powys (Pouos), stretching all the way back to the time of the Roman occupation of Britain.

Several quasi-mythical figures from this time are invoked, including Magnus Maximus (Maximus Brittanniae) the Roman usurper who died in 388 AD, Emperor Gratian (regem Romanorum) whom Maximus killed in 383 AD in order to seize power in Britain, St Garmon (Germanus), and Vortigern (Guarthigirn), the fifth-century British ruler who legendarily invited Saxons Hengist and Horsa to come to Britain to protect (southern) Britons against the depredations of the Picts.

Edwards shows that all of these figures are central to the origin story of the kingdom of Powys, and that the inscription as a whole is intended to glorify the kingdom, particularly as regards its historic victories over the English, and particularly those of Eliseg over the neighbouring Saxon kingdom of Mercia.

Another key insight is that the inscription was intended to be read aloud, and possibly to an assembled crowd. Edwards writes:

John Higgitt has drawn attention to the use of recit(a)uerit, indicating that the inscription should be read out loud to all those who could not read it for themselves. It may be possible to take this a stage further and to suggest that the inscription as a whole was intended to be proclaimed publicly.

Her conclusion is that the pillar is likely to have marked a place of political assembly and, given the emphasis of the inscription on royal genealogy, the origin story of the kingdom of Powys, and the heroic deeds of past warrior-kings, perhaps even a place of royal inauguration:

Its prominent location, commanding the valley of the Nant Eglywseg, was intended to signify the ownership of the land by the kings of Powys and its recovery from the English… One might take this a step further and speculate on whether the site could have been a focus of an assembly place and an inauguration site of the rulers of Powys, perhaps in the period after the land was reclaimed from the English.

Food for thought for Sueno’s Stone

For me, this already provides a lot of food for thought when thinking about Sueno’s Stone.

Sueno’s Stone doesn’t have an inscription, but its size and location make it a very good candidate for an assembly place. And some of its imagery, and the existence of apparently ritually-incised sword marks on the stone, strongly hint at its use in royal inauguration ceremonies.

Bearing these similarities in mind, I wonder if the famously-inscrutable battle scenes on its reverse were intended to work in a similar way to the inscription on the Pillar of Eliseg. Do they hark back to one or more mythical battles; victories of the ancestors or heroes of whoever had the stone put up? And do they form a narrative that was recited aloud at important events held at the stone?

Intriguing questions for sure, but I’m going to park them for now because there’s so much else to talk about.

Edwards’s paper rekindled interest in the Pillar of Eliseg and led to a major collaborative project between Bangor and Chester universities to discover more about its historical context.

Project Eliseg produced numerous academic papers, a thorough final report and a sporadic blog. It also made use of some novel approaches that I’m hoping to be able to apply to Sueno’s Stone too.

The landscape context of the Pillar of Eliseg

The approaches I’m particuarly interested in involve examining the Pillar of Eliseg in its wider landscape context. In the words of Professors Patricia Murrieta-Flores and Howard Williams of Project Eliseg:

The landscape can be considered far more than a backdrop in which social identities and social memories were inscribed and embodied through the raising and use of carved stones. Instead, locations and spatial settings are instrumental to the intended and acquired social and mnemonic significances of both recumbent and vertically raised, free-standing stones.

Murrieta-Flores, Williams and team used a Geographical Information System (GIS), an analytical tool for spatial data, to explore two aspects of the surrounding landscape in relation to the Pillar of Eliseg.

The first, using a technique called Cost Surface Analysis (CSA), focused on movement. It was used to identify routes through this mountainous part of Powys that would have presented the least effort to an early medieval traveller.

A second technique focused on visibility, or viewsheds: analysing which parts of the surrounding landscape would have been visible—or hidden—from where.

The results were published in a 2017 paper by Murrieta-Flores and Williams called Placing the Pillar of Eliseg: Movement, Visibility and Memory in the Early Medieval Landscape, which (I think) makes for fascinating reading.

There isn’t space to go into the findings here, but briefly, the first analysis reveals that:

The Pillar is… a key node in relation to a network of routes running east, west and north…

While the second reveals that:

…a key feature in terms of viewshed is that the Pillar is located in a very secluded location.

The landscape context of Sueno’s Stone

Both these techniques seem like they might be very valuable for understanding the landscape context of Sueno’s Stone. I’m not ready to think about visibility analysis yet, but I do have some thoughts about using Cost Surface Analysis to identify the relationship of Sueno’s Stone to potential early medieval routeways.

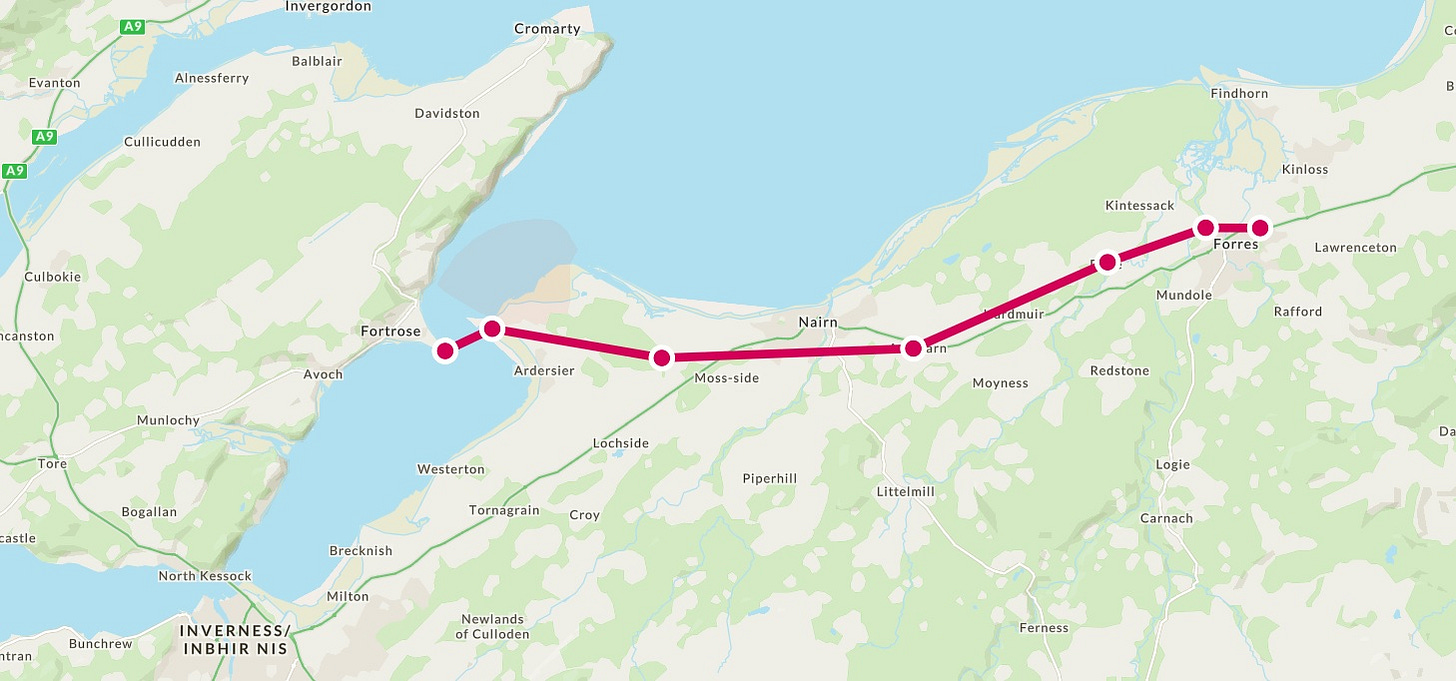

It seems highly likely that Sueno’s Stone sat on the main east-west route through Moray, as it still does today. But where exactly that route ran in early medieval times is less clear. I have a hunch that after Forres it ran closer to the coast than the modern A96, passing through two places with early medieval sculpture: Dyke with its fine Class II symbol stone, and Wester Delnies with its worn and neglected Class III cross slab, before crossing the Moray Firth via boat at Ardersier to Fortrose and the Pictish monastery at Rosemarkie (see rough map below).

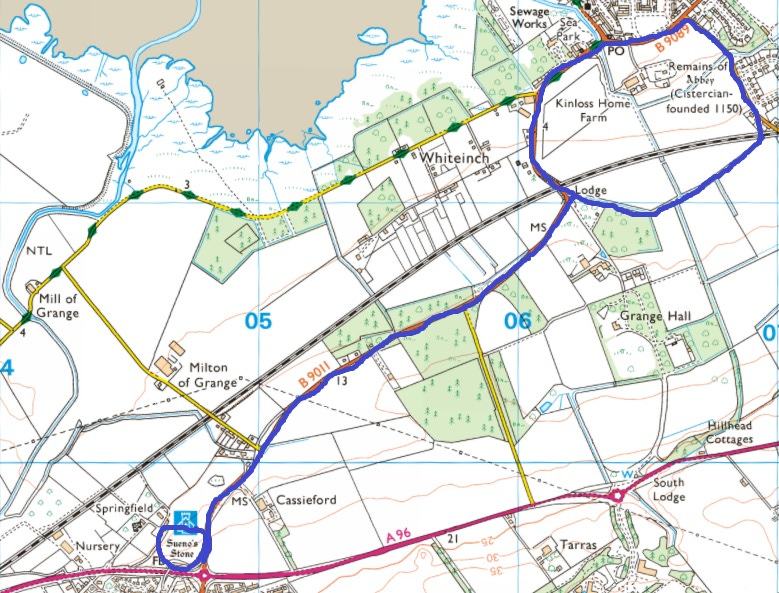

In an ideal world, Cost Surface Analysis could help me to assess whether this was a more likely early medieval route west of Forres than the one taken by the A96. It might also help to identify other natural routes in the vicinity of Sueno’s Stone. Today, the stone sits at the junction of the A96 and another road: the B9011 to Kinloss and Findhorn. Was this also a route taken by early medieval travellers—and if so, where were they going (or coming from)?

But there’s a problem here. The modern landscape around Forres is very different from how it would have been in (say) the ninth century, when a lot of the low-lying arable land of the Laich of Moray would have been marshy ground, shallow lochs, or even tidal estuary. So identifying least-effort early medieval routes using modern geographical data would be misleading. If I was to use this type of analysis I would first need to reconstruct in a GIS database the early medieval landscape around Forres.

This isn’t something that has been done before, although Dr Michael Stratigos has made in-depth reconstructions of the prehistoric and historic landscape around the (now-lost) Loch of Spynie, which show just how much the terrain in this part of Moray has changed. But I’m not a palaeogeographer and Stratigos’s methods are beyond me.

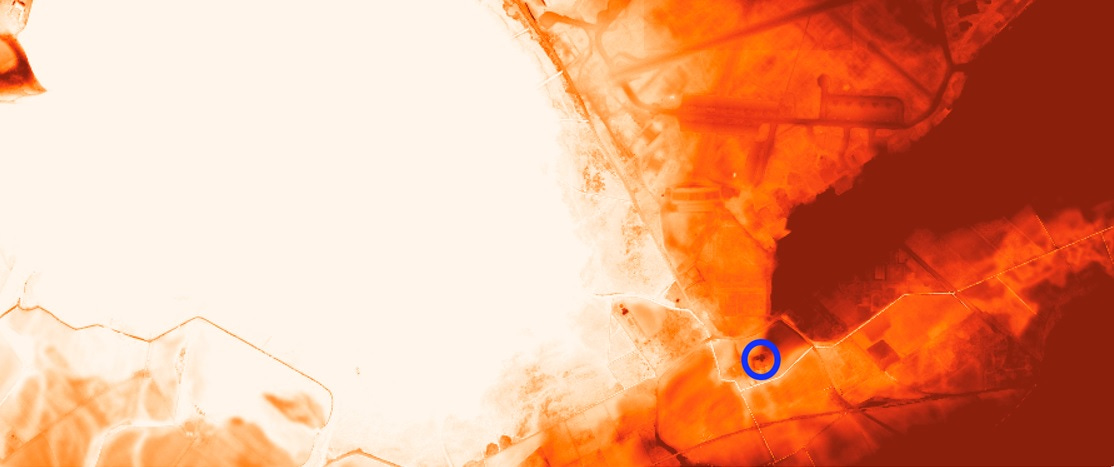

However, I think I might be able to make a bit of headway by examining local place-names and LiDAR data. For example, Cassieford and Inchdemmie on the B9011 between Sueno’s Stone and Kinloss hint at a causeway2 and an island respectively. Professor Leif Isaksen has also made me aware of LiDAR data that shows Kinloss Abbey (circled in blue below) on the tip of a spur of land jutting into a very low-lying area, which could well have been marsh or estuary in the early medieval period.

Here too, Project Eliseg has given me food for thought. Like Eliseg, Sueno’s Stone started out as a slab of local rock, specifically the sandstone that outcrops naturally around Burghead.3 In Placing the Pillar of Eliseg, Murrieta-Flores and Williams write about a possible ceremonial dimension to the movement and installation of the Pillar:

The transportation and carving of the monument might together have operated as a form of public performance operating at a landscape scale. The final monument would subsequently commemorate this act of extracting and moving the stone up the Dee, and would perpetuate knowledge of its relationships to its source, the route taken, and other locations en route, as well as enhancing its final locale.

Given that Sueno’s Stone consists not only of the huge 7m slab that makes up its visible portion, but also a huge 10-ton socket stone buried in the ground, transportation and installation would have been a major logistics project—and it’s not hard to imagine it being a ceremonial public spectacle.

If I could prove the presence of navigable water nearby, I could make an argument for the stone(s) being brought by boat from Burghead, mooring somewhere below the ridge on which the stone sits. But that has to remain pure speculation for now.

Untangling the Cistercian connection

Finally, there’s the intriguing coincidence that the Pillar of Eliseg and Sueno’s Stone are both located near Cistercian abbeys; respectively Valle Crucis and Kinloss. Or, since the stones long pre-date the abbeys, it’s more accurate to say that Cistercian abbeys were founded close to the monuments.

In the case of Valle Crucis, it does actually seem likely that the pillar was the magnetic factor. The abbey was named after it—'Valle Crucis’ means ‘Valley of the Cross’—and Murrieta-Flores and Williams observe that:

The cross had remained an enduring medieval landmark adapted into the Cistercian monastic landscape during the 13th century…

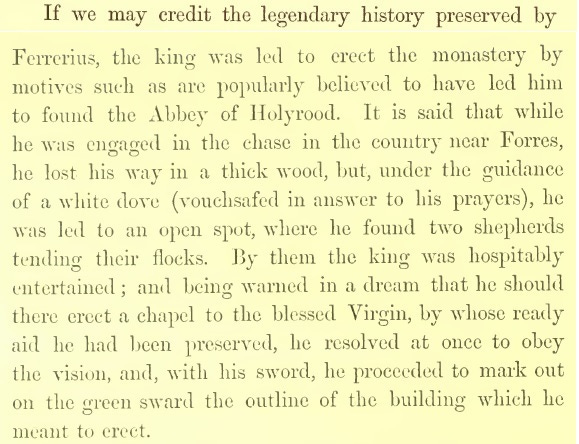

Could a similar argument be made for Kinloss? It is true that it’s further away: 3.5km from Sueno’s Stone, while Valle Crucis is only 400m from the Pillar of Eliseg. But a decision was made to build Kinloss Abbey in the spot where it is, and we can’t give much credence to the foundation legend, which tells of David I getting lost while out hunting and being given shelter by some shepherds, during which time he had a dream that the Virgin Mary appeared and told him to build an abbey on this spot.

Perhaps more likely—though there is no archaeological evidence for it—is that there was already an ecclesiastical foundation on the site of Kinloss Abbey, which David I confiscated and re-granted out to the Cistercian Order. This is an argument that is also made for Valle Crucis, with Edwards writing:

The monument is not associated with any known early medieval ecclesiastical site, though the alternative Welsh name associated with the abbey, Llanegwestl, hints at the existence of an earlier foundation. It should be noted, however, that at least some Cistercian houses in Wales, notably Margam (Bridgend) and its granges, were on the sites of early medieval ecclesiastical foundations indicated by the presence of early medieval sculpture.

In this case, the Pillar of Eliseg could have formed part of an ecclesiastical landscape at the time it was raised. And although I don’t have enough evidence yet to make a firm argument, I have a growing hunch that Sueno’s Stone may also have stood at the entrance to, or boundary of, an early medieval ecclesiastical foundation at Kinloss.

Again, it’s the modern B9011 road that’s prompting me to think this. Poring over the Google Maps aerial view a couple of years ago, I noticed that the road bends sharply as it approaches Kinloss, then follows a curved route around the abbey on its way to Findhorn. But that’s not all: this curve clearly extends all around the abbey, coming back to meet the B9011 just by the lodge of Grange Hall, as I’ve outlined in blue below:

If this is the line of an old enclosure, it’s a massive one – and it doesn’t look like any other Cistercian precincts that I’ve looked at online. If any archaeologists are reading, I’d be grateful for your thoughts: does this look like an early medieval enclosure, or does it look like it might be contemporary with the twelfth-century abbey?

If it’s an earlier site, I think there’s something to be said for it being at the end of a short stretch of road that starts at Sueno’s Stone:

If only there was any archaeological evidence for an early Christian site here! But sadly the one find of early medieval sculpture from Kinloss turned out to be a red herring.

UPDATE: But there are these interesting cropmarks:

That’s all for now…

I did have even more to say about the parallels between the Pillar of Eliseg and Sueno’s Stone, but I’m at 3,500+ words now and I don’t want to detain you for too long.

I would like to come back to it another time, though—as there are some really interesting thoughts by both Edwards and Williams about the Romanitas (parallels with Roman sculpture) of the Pillar of Eliseg; about the way its inscription moves the audience backwards and forwards in time; and about its political significance in a contested frontier region between Powys and Mercia.

All of these theories could also be applied to Sueno’s Stone, so I think I’ll give them some thought and come back with another blog. In the meantime, thanks very much for reading, and I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

References

Nancy Edwards, “Rethinking the Pillar of Eliseg,” The Antiquaries Journal 89 (2009): 143–77.

Nancy Edwards, Gary Robinson, Howard Williams and Carol Ryan Young, “Excavations at the Pillar of Eliseg, Llangollen, 2010-2012: Final Report” (2014).

Heather F. James, “Pictish cross-slabs: an examination of their original archaeological context,” in Able Minds and Practised Hands: Scotland’s Early Medieval Sculpture in the 21st Century, Routledge 2005.

Neil McGuigan, Máel Coluim III Canmore: An Eleventh-Century Scottish King. Birlinn, 2021.

Patricia Murrieta-Flores and Howard Williams, “Placing the Pillar of Eliseg: Movement, Visibility and Memory in the Early Medieval Landscape,” Medieval Archaeology, 61:1 (2017), 69–103.

Michael Stratigos, A Model of Coastal Wetland Palaeogeography and Archaeological Narratives : Loch Spynie, Northern Scotland, Journal of Wetland Archaeology, 2021.

John Stuart ed., Records of the Monastery of Kinloss with Illustrative Documents, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1872.

UPDATE 1st May 2023: I’ve now remembered that Dr Neil McGuigan does make this point on p. 60 of his book on Máel Coluim III (Malcolm Canmore): “Forres hosts one of the largest and most impressive pieces of monumental sculpture to survive from pre-Norman Britain, Sueno’s Stone, possibly erected in the tenth century. Today it stands alone… but around 1000 [it] most likely stood alongside several other impressive monuments… In the twelfth century… David I took direct control of Áengus [mormaer of Moray]’s land and founded a Cistercian monastery near Forres, Kinloss Abbey. Situated on the edge of such an important Viking Age centre it is likely that Kinloss Abbey’s Cistercians took over from an earlier monastic house, perhaps one of Pictish origin.”

Thanks to Professor Hector MacQueen for this observation.

Thanks to David McGovern of Monikie Rock Art who made this observation on Facebook (I think!)

Thanks, Fiona. I'll certainly look at this paper, first opportunity. Note than when I looked at this for the thesis I classified the name as antiquarian, so not claiming it as contemporary with those who may have used the monument as the comparison implies. Would be wonderful to know what those coining the name knew / thought of them though!

May your GIS plan, to fruition come...

Very interesting and persuasive - thank you! You might be interested in what I said about Sueno's Stone in my PhD on ethnonyms in place-names https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/handle/10023/4164

p42

A further Cruithnian-name, assuming translation, is a boundary feature for Burgie

in Moray. Recorded in 1221 as a hybrid in a Latin context, Rune Pictorum† RAF-MOR

seems to be a field associated with the twenty-foot sculptured Sueno's Stone. In the light

of the other Cruithnian-names, the safest conclusion is that this, too, is antiquarian in

motivation.

Appx p261 (formatting lost)

Rune Pictorum RAF-MOR † (Rafford). Antiquarian name. Ch. 3 Cruithnians: probable.

NJ046595 (?).

A boundary marker for Burgie {Grant & Leslie 1798} (Shaw 1882 i, 13). Sueno's Stone – a

20' sculptured monument (Canmore, 15785).

'The carne of the Pethis or the Pechts seildis [sic]' (REM no. 4 p. 457). 'The carne of the

Pethis or the Pechts feildis', probably associated with the Forres sculptured pillar [Sueno's

Stone] (REM, xxx). 'The Picts' cairn' {Grant & Leslie 1798} (Shaw 1882 i, 13).

1221 Rune Pictorum (acc.) (REM, xxx; REM no. 4 pp. 456, 457)

ScG n.m/f. raon + gen. pl. of Ln n.m. *Pictus

ScG *Raon Chruithneach – 'field associated with the Picts'

The generic in Rune Pictorum also appears in Runetwethel (acc.), 'field associated with

ScG masc. anthro. Tuathal'. Both names are in a list of boundary marks for Burgie, along

with other clearly Gaelic names. Rather than a loan word in untypically incorrect Latin

grammar, this appears to be undeclined ScG n.m/f. raon 'field' in Older Scots orthography.

The grid reference is supplied by Sueno's Stone, (re-)erected at the apex of a spur of the

parish of Rafford MOR near Burgie. Translation of the Gaelic ethnonym is assumed. The

REM interpretations comes from a MS translation of four names from Gaelic to Older

Scots which was added to the original charter; but interpretation as 'cairn' has no obvious

basis. The plural interpretation of rune in REM may be seeking to make the reference

agree with Latin grammar.