A Moray location for the battle of 'Sraith Herenn'?

In which I ponder whether Sueno's Stone commemorates a victory of Constantín II of Alba over the Vikings in 904 AD.

Causantín mac Aeda held the kingdom forty years. In his third year the Northmen plundered Dunkeld and all Albania. The very next year the Northmen were slain in Sraith Herenn.

So the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, possibly the only contemporary local source we have for events taking place in Gaelic Scotland in the Viking Age, described what must have been one of the greatest victories of one of its most remarkable kings, Constantín II of Alba.

By 904, when Constantín and his army slew them in ‘Sraith Herenn’, the ‘Northmen’ had been laying waste to Pictland for around 100 years. One of their earliest targets was almost certainly the great monastery at Portmahomack on Tarbat Ness, where a violent event around the turn of the ninth century saw workshops burned to the ground and stone sculpture smashed into pieces.

In 839, another Viking attack resulted in the deaths of Eógánan king of the Picts, his brother Bran, and Áed, king of neighbouring Dál Riata (modern Argyll). This catastrophic event created a power vacuum in both kingdoms, which by 843 had been filled by one man: Cináed mac Alpin, the first king of a unified polity that spanned northern Scotland from the Atlantic to the North Sea.

Cináed’s grandson Domnall, who reigned as king of the Picts from 889 until his death in 900, also seems to have met his end—whether at Dunnottar or Forres—fending off Norse attackers. And only three years later, as the Chronicle states above, ‘the Northmen plundered Dunkeld and all Albania.’

The secret weapon of the men of Alba

After such a relentless string of setbacks, the situation faced by Domnall’s successor Constantín II must have seemed desperate.

But as they marched into battle against the Northmen in Sraith Herenn in 904, Constantín and his men had with them a secret weapon: a holy relic, the crozier of St Columba, which they had nicknamed in Gaelic Cathbuaid, or ‘Battle Triumph’.

The Cathbuaid isn’t mentioned in the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba. In fact the Chronicle doesn’t ascribe any agency at all to Constantín or his army, falling back on the passive voice to note simply that ‘the Northmen were slain’.

But the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, a collection of records of notable events kept by contemporary Irish monks, has quite a lot to say on the matter. It identifies the leader of the Northmen as Imar (Ivar), the exiled king of Viking Dublin and grandson of the legendary Ivar the Boneless, and says:

When Imar […] came to plunder Alba with three large troops, the men of Alba, lay and clergy alike, fasted and prayed to God and Colum Cille [i.e. Columba] until morning, and beseeched the Lord, and gave profuse alms of food and clothing to the churches and to the poor, and received the Body of the Lord from the hands of their priests, and promised to do every good thing as their clergy would best urge them, and that their battle-standard in the van of every battle would be the Crozier of Colum Cille—and it is on that account that it is called the Cathbuaid 'Battle-Triumph' from then onwards; and the name is fitting, for they have often won victory in battle with it, as they did at that time, relying on Colum Cille.

The victory in Sraith Herenn—in which Ivar grandson of Ivar was killed, according to the Annals of Ulster—must have seemed to Constantín and his men like divine intervention.

It may even have seemed like divine retribution, since Dunkeld, which the Northmen had ransacked the previous year, may well have been the place where Columba’s sacred crozier was kept. The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba says that in c. 849, Cináed mac Alpin brought Columba’s relics from Iona to “the church that he had built”, which historians usually identify with Dunkeld.

Where exactly was ‘Sraith Herenn’, though?

So where did this miraculous victory actually take place? Given the association with Dunkeld, the obvious conclusion would be that ‘Sraith Herenn’ is Strathearn, the valley of the River Earn in Perthshire. But that’s far from a given, for two reasons.

The first is that the label ‘Strathearn’ seems to have been applied to a very broad geographical area in the early middle ages. The 19th century Scottish historian William Forbes Skene noted that:

In the tract on the mothers of the saints, which is ascribed to Aengus the Culdee, in the ninth century, we are told that ‘Alma, the daughter of the king of the Cruithnech’, or Picts, ‘was the mother of Serb, or Serf, son of Proc, king of Canaan, of Egypt, and he is the venerable old man who possesses Cuilenros, in Stratherne, in the Comgells between the Ochill Hills and the sea of Giudan.’

Which suggests that in the ninth century, Culross, about 45km from the river Earn on the south coast of Fife, was considered to be in ‘Strathearn’. In a paper that explores the use of the word ‘earn’ as a place-name element, Thomas Owen Clancy cites the above quote from Skene and adds:

The account of the Mothers of Irish Saints underlines the fact that we are dealing not just with the strath of the river Earn here, but with a more complex regional unit. [my emphasis]

The second reason to question modern-day Strathearn as the location of the battle, as Alex Woolf famously pointed out in his 2006 paper Dún Nechtain, Fortriu and the Geography of the Picts, is that there was more than one Strathearn in the Pictish heartlands:

There are at least two places in Scotland with this name. In Perthshire […], there is Strathearn; but north of the Mounth Strathdearn, the valley of the Findhorn, the ‘White Earn’, bears this name. The battle in Srath Éireann may, then, have taken place either north or south of the Mounth.

So it’s at least possible that the battle of Sraith Herenn took place in the northern Strathearn. But if it did, should we be looking for a site along the River Findhorn, or, like the southern Strathearn, should we be thinking about a larger regional unit?

A ‘Greater Strathearn’ in Moray and Nairn?

There is in fact a small amount of evidence for a larger district: two ‘Earn’ place-names that lie close to the River Findhorn but not close enough to be considered to be in its valley.

One of these is Auldearn, near Nairn. A land grant of 1140 to the Priory of Urquhart mentions a ‘Pethenach near Eren’, which led place-name scholar W. J. Watson to conclude:

Pethenach is now, I think, Penick, near Auldearn church. This Eren was therefore in Nairnshire, and appears to have been the old name for Auldearn parish. In any case it is the name of a district. [my emphasis]

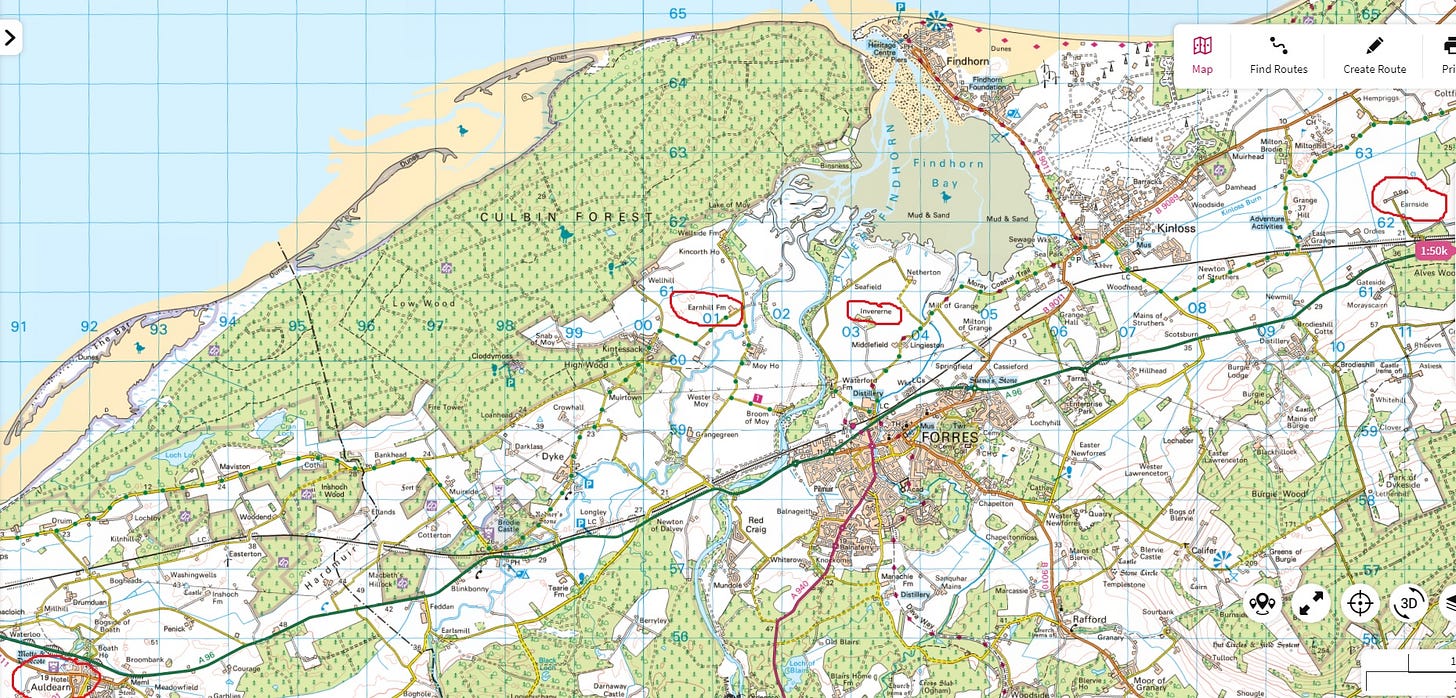

The other name, not noted by Watson or Clancy, but explored on this very blog a few months ago, is Earnside, near Alves.

This was the site (and name) of a 15th-century castle, but unless the Findhorn has changed its course very dramatically since 1450, that castle wasn’t built at the ‘side’ of the ‘Earn’. In fact Hector MacQueen suggested in the comments on that blog that the ‘side’ in its name may have referred to its position on a hillside, rather than beside the river.

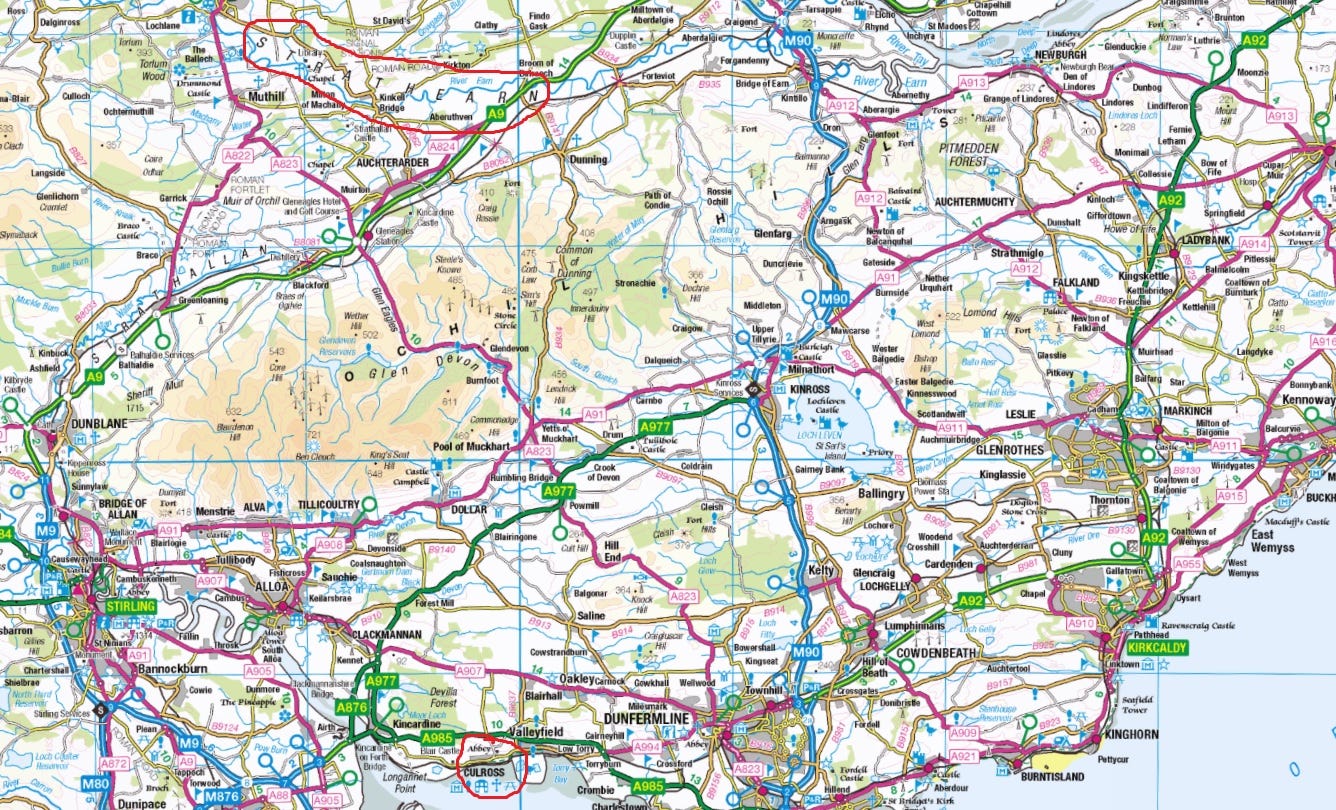

So it’s just possible to imagine some kind of medieval ‘regional unit’ named Strathearn, which straddled the Findhorn, taking in Auldearn in the west and Earnside in the east (see map below).

Clancy thinks there’s definitely something in this idea, writing:

There is considerable evidence of widespread use of the term Eren in Moray and it is difficult to completely explain this by recourse to hydronyms; one significant site, Auldearn, cannot be explained this way.

Clancy’s tentative theory—and Watson’s before him—is that these place-names are derived from ‘Ériu’, meaning Ireland. He suggests that, alongside others like Elgin, Banff and Dunphail, they hint at an idea of a ‘New Ireland’, indicating places settled by Gaels recalling their homeland.

It’s quite a difficult idea to countenance, and luckily for the purposes of this blog, perhaps not relevant. Clancy suggests that this wave of conscious ‘New Ireland’ naming took place closer to the 12th century than the 10th:

If Eren, Elgin, and Banff are coinages of this sort, it may be thought they belong to a particular moment in the settlement history of the North-East, one in which an appreciation of the pseudo-history and the poetic naming of Ireland was present, and one when the Irish identity of the Scottish kingship was to the fore. Given their status as central places during the twelfth-century conquest of Moray, it may be that that moment was not very far distant from it.

So perhaps we can discount the idea of a ‘greater Strathearn’ in Moray in the 10th century, and focus just on the immediate environs of the Findhorn. Is there any other evidence that the battle of Sraith Herenn might have take place near the River Findhorn, rather than in Strathearn in Perthshire?

Is this the battle commemorated on Sueno’s Stone?

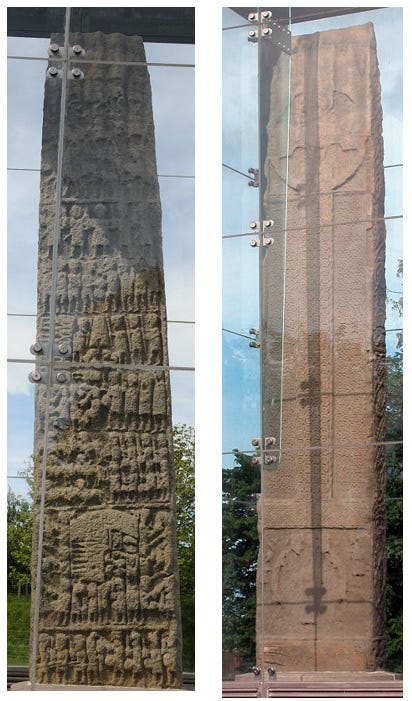

Well, we could at least consider Sueno’s Stone, overlooking the mouth of the Findhorn on the eastern edge of Forres, in this context. At nearly 7m tall it was unquestionably designed to communicate or commemorate something momentous. And its reverse face features a series of extremely graphic battle scenes, while its front face bears an enormous ring-headed cross.

As I’ve noted on this blog before, its art style suggests it was carved in the period 850-950 AD, right into the middle of which the battle of Sraith Herenn falls. It stands alone, unconnected to any known 9th or 10th century church or settlement site. And for what it’s worth (probably not a lot, as earlier historians saw ‘Danes’ everywhere), throughout its written history it has been associated with a victory over the Vikings.

It's not too much of a stretch to imagine this place as the point at which the men of Alba assembled prior to the battle of Sraith Herenn. Sueno’s Stone stands on a fork in two ancient routeways – one heading towards Elgin, the other towards Burghead. It also stands beneath the site of an enormous late Bronze Age / early Iron Age hillfort, which would still have been a prominent landmark in the early medieval period. A crossroads below a huge hillfort is a very findable location, ideal for mustering troops.

The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland suggest that Sraith Herenn was the first time the Men of Alba had taken the Cathbuaid—St Columba’s crozier—into battle, despite it having been in mainland Scotland for some 50 years (assuming it was one of the relics that Cináed mac Alpin had brought from Iona in 849). They even imply it was the first time the men of Alba had fought a battle in Columba’s name.

Could we imagine Constantín rallying his troops beneath the hillfort at Forres, urging them to fight in the name of Columba, reminding them that the Northmen had just the previous year ransacked Dunkeld where (historians assume) Columba’s sacred relics were kept?

Might he even have intimated to them that Columba had appeared to him in a dream, assuring him of certain victory—in the style of his namesake, the Roman emperor Constantine the Great, at the battle of the Milvian Bridge?

If anything of that nature actually happened, that rallying point would seem an ideal location to raise a memorial to the triumph that ensued; the enormous Iona-style cross reflecting the critical role played by Columba and God in ensuring victory for Constantín and his army.

Several scholars have commented on Sueno’s Stone Romanitas; its echoes of Roman triumphal architecture. Did Constantín consciously consider himself in the mould of a Roman emperor, particularly the one he may actually have been named after? If so, a triumphal monument in the Roman style would be very in keeping.

In conclusion: Maybe, maybe not

Obviously, the answer to all that is: we can never know. And although I like this theory, part of my reason for writing this blog is to show that when there’s so little surviving evidence, it’s very easy to put two and two together and make 28.

To recap, all I know for just-about-certain is:

A battle took place in 904 AD between Constantín II and an army of Norsemen led by Ivar grandson of Ivar, which Constantín and his army won, and in which Ivar was killed.

This battle followed close on the heels of an event the previous year in which the same band of Norsemen had plundered Dunkeld.

The battle took place in ‘Sraith Herenn’, which could have been Strathearn in central Scotland, a wider area taking in Fife, or the environs of the River Findhorn in north-east Scotland.

Constantín’s army took a holy relic of St Columba, his crozier, into this battle, adopting it as their battle-standard.

Sueno’s Stone was likely raised sometime between 850 and 950 AD, at the meeting of two routeways beneath a hillfort near the mouth of the Findhorn, and it seems to commemorate a mighty battle, perhaps fought in the name of God.

All further embellishments and drawing together of threads are simply due to my brain looking to create a pleasing pattern. And there are plenty of things that don’t fit, notably:

This theory doesn’t explain why Sueno’s Stone also includes what seems to be a royal inauguration scene beneath the cross.

It’s marginally more likely that ‘Sraith Herenn’ was the Perthshire Strathearn, given that the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba mentions it in the same breath as the plundering of Dunkeld, and the geographical focus of the Chronicle is in the south generally.

The kings of Alba seem to have been based around Dunkeld, Forteviot and Scone, making Forres quite a remote location to invest in such a grand piece of sculpture. (It’s not entirely impossible that they did have links to Forres, though, as I explored in this blog).

But I do think this theory has more going for it than the one linking Sueno’s Stone to the death of king Dubh of Alba in 966, so I’m probably not going to completely discount it just yet—unless anyone wants to talk me out of it in the comments!

P.S. I ‘borrowed’ the title of this post from the title of Professor Clare Downham’s paper A Wirral Location for the Battle of Brunanburh, which I meant as a nod to Constantine II’s much more famous battle, but I now feel a bit uneasy about not crediting her - so here’s the credit. (Added to the references too.)

References

M. Carver et al, Portmahomack on Tarbat Ness (2019)

T.O. Clancy, Atholl, Banff, Earn and Elgin: ‘New Irelands’ in the East Revisited (2010)

C. Downham, A Wirral Location for the Battle of Brunanburh (2021)

S. Driscoll, A Tale of Two Constantines: Weighing up the Influence of Imperial Models of Rulership on Scottish Kingship (2022)

I. Henderson and G. Henderson, The Art of the Picts (2004)

L. Isaksen, The Hilltop Enclosure on Cluny Hill, Forres: description, destruction, disappearance (2017)

L. Izzi, ‘Trajan’s Column on his doorstep’: investigating the Romanitas of Sueno’s Stone (2013)

W. J. Watson, The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (1927)

A. Woolf, Dún Nechtain, Fortriu and the Geography of the Picts (2006)

A. Woolf, From Pictland to Alba, 789-1070 (2007)

A bit late to this (brought back by your wonderful Auldearn post) but surely one argument for a northern location is simply that the Annals of Ulster record it as a victory for the men of Fortriu ("la firu Fortrenn" - AU 904.4)?

Assuming the identification of Fortriu with the north is correct, and assuming the narrative of a shift in the centre of power to south of the mounth post-839 is also correct, it seems inherently unlikely that it would be the army of the (weaker) north that was defending the (stronger) south against vikings deep within southern territory in Strathearn in 904? Woolf argues against 904 being used as evidence for Fortriu being equated with Strathearn on the basis that "It could have been an away match", but in fact it would have been an away match for both sides - the Vikings and the men of Fortriu fighting each other within the heartland of southern Alba. A northern location of the battle, with the men of Fortriu defeating the Vikings while defending their own heartland in the hinterland of Forres does seem on the face of it more likely.

An alternative (or possibly complementary) interpretation of the AU description might be that the post-839 power dynamic between north and south was a bit more complicated. As you touched on in your earlier post of Forres, Woolf ("Pictland to Alba", pp223-224) and McGuigan ("Mael Coluim II", pp51-55) both suggest this, but come to diametrically opposite conclusions from the same evidence - that no descendants of Causantin mac Cinaeda died south of the Mearns, while only one descendant of Aed mac Cinaeda didn't. McGuigan argues that this shows that Forres was part of Clann Causantin's home territory, and that they were thus based in the north; while Woolf argues that it shows that Clann Causantin was based in the south, with Clann Aeda being based in the north, as the demise of Clann Aeda coincides with the rise of the Moray-based Clann Ruadri in their place.

If it is Woolf's conclusion that is correct, then Causantín mac Aeda's powerbase would have been in the north, which might explain why it was specifically the men of Fortriu fighting the Vikings in 904, wherever the battle took place. This might also explain the line immediately before the section you quoted from the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, which seems to directly equate the "men of Fortriu" with the "men of Alba" later in Causantín's reign in 918: "?918 Almost at the same time the men of Foirtriu and the Norwegians fought a battle. The men of Alba fought this battle steadfastly, moreover, because Colum Cille was assisting them".

But then, if Causantín mac Aeda's power was centred in the north, doesn't that itself make a northern location for 904 more likely?

Excellent as always. Assuming the southern Stathearn this also fits with earlier raiding like the battle of dollar. The Roman road of course ran along strath Allan and strath earn and would be the obvious route for raiders from the coast trying their luck? Might the victory be explained by being caught too far from safety along the road. Lots of supposition of course!