Sueno's Stone: an 8th, 9th, 10th or 11th century monument?

In which I grapple with the thorny topic of when this extraordinary stone was carved

A comment thread on my blog about Kinneddar has raised the difficult question of the dating of Sueno’s Stone. Many historians avoid the topic, but as Sueno’s Stone is at the core of my forthcoming MA research, it’s one I can’t really dodge.

I’d seen the range 850-950 AD cited many times, and all the outliers I was aware of put it later, so I was a bit thrown by the suggestion that consensus now puts it in the mid-700s. Had I missed some new research? This blog summarises my efforts to find out.

An anomaly in an otherwise ‘Pictish’ landscape

First, some context. Dating Sueno’s Stone is a difficult topic because the stone is in many ways an anomaly. It sits in a landscape along the southern shore of the Moray Firth that’s dotted with culturally ‘Pictish’ carved cross slabs: the Elgin Pillar, the Princess Stone, Rodney’s Stone, the Kebbuck Stone, the Altyre Cross.

Sueno’s Stone belongs with these stones in the sense that it’s also a cross slab, bearing an enormous ringed cross on its west face. But there are also big differences. At 7m tall it’s more than twice the height of the Altyre Cross, the tallest of the others. And unlike the Elgin Pillar, the Princess Stone and Rodney’s Stone, it doesn’t bear any of the mysterious symbols that characterise ‘Pictish’ stones.

The iconography on its east face is quite unlike any other stone in northern Pictland. In place of the loose, flowing hunting scenes and intricately carved symbols of the diagnostically Pictish stones, Sueno’s Stone has a series of grisly, claustrophobic battle scenes, with rows of warriors engaged in bloody massacre, the decapitated bodies and heads of the enemy steadily piling up around them.

Perhaps the most perplexing element of Sueno’s Stone is the scene immediately below the cross. It’s been severely defaced (why?) at some point, but it seems to depict a royal inauguration. Yet Forres is around 200km north of the known early medieval inauguration sites of Forteviot and Scone, and no scene like this exists on any other early medieval carved stone in Scotland.

What’s the significance of Forres?

Its location is odd in other ways, too. Standing just east of Forres, Sueno’s Stone is close to the important, and probably royal, Pictish sites of Burghead and Kinneddar, but not so close that it could readily be interpreted as being part of a coherent royal landscape. (Burghead is around 17km distant, and Kinneddar about 28.)

There are traces of a Pictish presence in Forres: a Class I symbol stone was found in St Leonard’s Road, and there’s a high-status Pictish barrow close to the River Findhorn at Greshop. But there’s no evidence of an early medieval church or fort to which Sueno’s Stone might ‘belong’.

(There was an enormous Iron Age fort on Cluny Hill above Forres, but recent excavations have revealed no hint of Pictish re-occupation.)

An 11th-century victory over the vikings?

All of this makes Sueno’s Stone very hard to date and interpret. Debate about when it was raised, who by and what for has been ongoing since at least 1726, when Alexander Gordon, on an antiquarian tour of Scotland, connected its battle scenes to a victory of Malcolm II at Mortlach:

Why this Obelisk was rais’d, or how to explain the several Figures thereon, I am at a Loss, but cannot forbear thinking that it was erected by the Scots after the Battle of Murtloch.

Gordon was one of the first to try to date the stone by linking its battle scenes to an actual historical event. A medieval scholar, John of Fordun, relates that Malcolm II defeated an army of vikings near Mortlach (modern Dufftown) shortly after his accession in 1005. If Gordon was correct, it would place the stone in the early 11th century.

Is Sueno’s Stone Pictish, Scottish or Picto-Scottish?

Today, however, the consensus (unless I’ve missed something) is that Sueno’s Stone was raised earlier than that: some time in the 9th or 10th century.

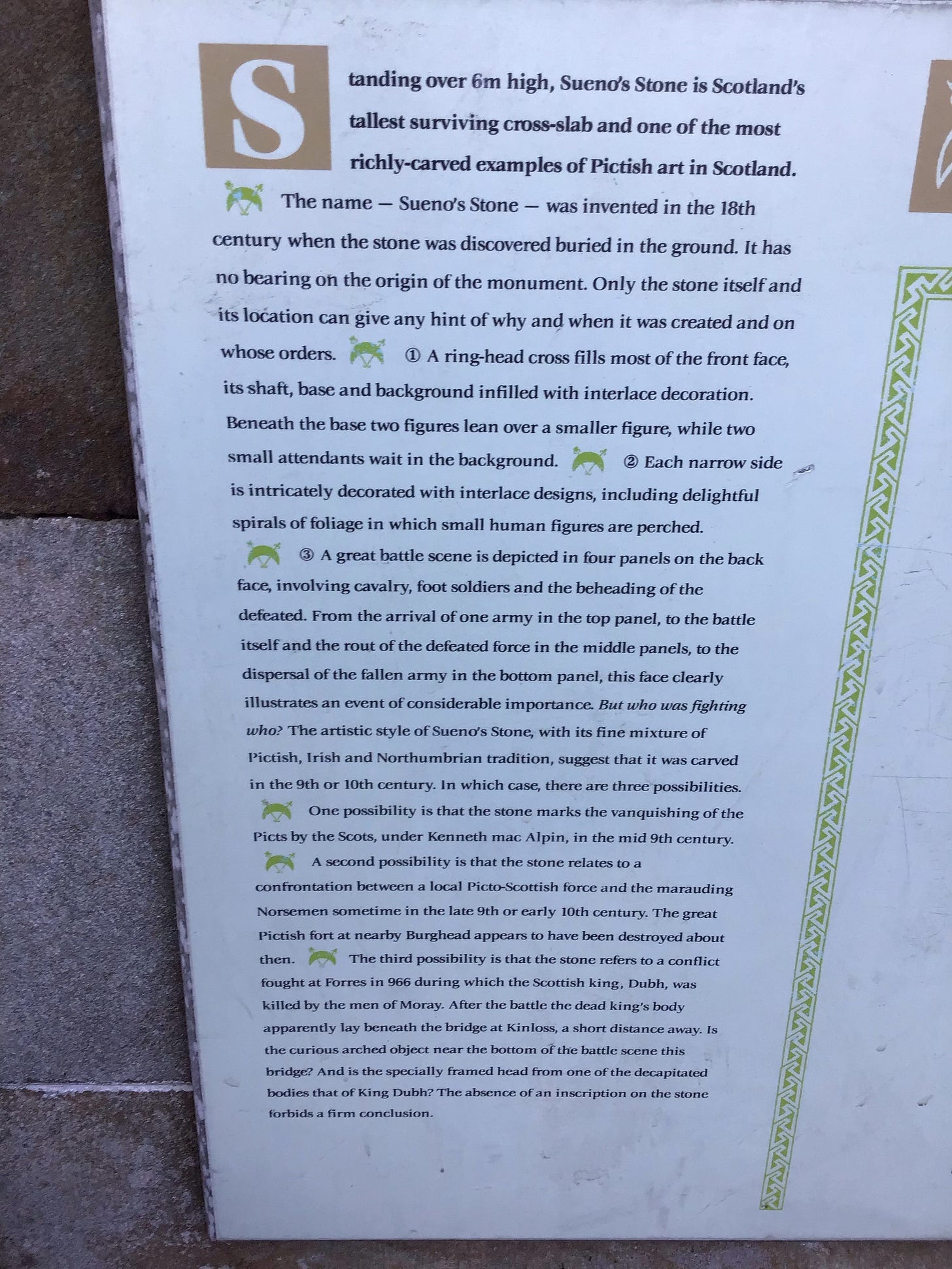

Historic Environment Scotland, the lead body responsible for the care of the stone, proposes ‘mid AD 800s or early AD 900s’ on its web page for Sueno’s Stone, while its interpretation board at the site itself reads:

The artistic style of Sueno’s Stone, with its fine mixture of Pictish, Irish and Northumbrian tradition, suggest that it was carved in the 9th or 10th century.

It’s a controversial date range, for a couple of reasons. One is that it places Sueno’s Stone in the post-Pictish period, after an episode in 842 or 843 when the throne of Pictland was seemingly seized by a ‘Scot’ (Gaelic speaker), Cináed mac Ailpín (Kenneth McAlpin), ruler of the neighbouring kingdom of Dál Riata (Argyll).

Very little is known about the circumstances of this apparent power grab, but it still lives deep in the psyche of eastern Scots, who to this day can be found on Twitter lamenting the ‘genocide’ of their Pictish ancestors and the death of the Pictish language at the hands of Gaelic-speaking ‘invaders’.

Placing Sueno’s Stone after this time implies that it’s not strictly a work of Pictish art, like the other stones in the area, but a hybrid or foreign implant, perhaps even an expression of conquest and subjugation. My reading of modern feelings towards the stone is that people would prefer it to be an unequivocally Pictish monument – something to be proud of, rather than uneasy about.

Another reason it’s controversial is that it isolates the stone in time. The heyday of stone sculpture in northern Pictland is generally held to be the mid-8th century, when the magnificent carvings discovered at and around the short-lived Pictish monastery at Portmahomack were produced.

If stone sculpture was still flourishing around the Moray Firth in the 9th and especially 10th centuries, why are there not more monuments like Sueno’s Stone in the region? And if it had gone into terminal decline, where did the skills and resources to design and carve this exceptional monument come from?

How do you date a stone? Three main approaches

Those concerns notwithstanding, most modern historians, archaeologists and art historians have coalesced around a 9th or 10th century date.

But that’s based on very uncertain evidence, drawn from three main sources: the art style of the stone; the possibility that the battle scenes represent an actual historical event or series of events; and scientific dating evidence picked up during archaeological investigations at the site.

Art style: interlace, tightly-packed figures, and military iconography

Art historians have made most of the running in dating the stone, by comparing its form and style with other monuments whose dates are known, or at least more secure.

For them, the key diagnostic elements are the acres of interlace on the cross face, and the rows of figures and martial imagery of the battle scenes.

In The Problem of the Picts, a 1955 collection of essays that rekindled academic interest in the Picts, R.B.K. Stevenson observed stylistic similarities between Sueno’s Stone’s and the “Anglo-Danish style of tenth-century Northumbria”, as well as Irish high crosses of the same period:

Sueno’s Stone at Forres, though over 20 feet high and skilfully carved, bears in its design the stamp of the same late period—the monotonous interlacing and more particularly the rows of tightly packed figures such are found on Irish high crosses of the time.

Archaeologist Anna Ritchie, in a 2000 book for Historic Scotland called Invaders of Scotland, echoes Stevenson’s assessment and attempts to resolve the ‘Pictish or Scottish’ dilemma:

The artistic style of Sueno’s Stone suggests that it was carved in the 9th or 10th century by a Pictish sculptor working for a Scottish patron, since the panels of figures are a device that became typical of Irish crosses in the 10th century.

In their epic 2004 survey The Art of the Picts, Isabel and George Henderson offer the earliest mainstream dating for the stone, pushing it back perhaps as far as the end of the Pictish period.

They compare its military iconography to that of the Dupplin Cross, whose inscription – a dedication to the Pictish king Constantín mac Fergusa (d. 820) – makes it securely dateable to around 800 AD.

Noting that Sueno’s Stone may once have been one of a pair of carved pillars, the Hendersons say:

Sueno’s Stone is […] as likely to be a conscious cultural gesture by a 9th century patron who wanted the equivalents of the Columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius on his doorstep, as that we should regard the camp scenes, parades and massacres as an intelligible act of local reportage.

(This raises the question: whose doorstep was in Forres in the first part of the 9th century? But that’s a topic for another time!)

Most recently, in Crucible of Nations, his 2021 book on Viking Age material culture in Scotland, Adrián Maldonado echoes Stevenson’s views about the similarities with Irish high crosses:

Pictish or not, the consensus is that Sueno’s Stone is ‘late’, a cross-slab with no symbols, with legions of soldiers and riders recalling the crowds depicted on the Irish high crosses of the 9th and 10th centuries.

Identifying the battle: From Cináed mac Ailpín to the Battle of Carham

Historians, for their part, have long tried to date the stone by relating the battle scenes to known historical events. While this approach is probably the most fun, it has produced an unhelpfully wide range of dates.

Archie Duncan, in his 2002 book The Kingship of the Scots, doubled down on his 1984 theory that the battle scenes represent the death of king Dubh of Alba. According to the later medieval king-lists, Dubh was murdered in Forres in 966 and his body hidden under the bridge at Kinloss. Duncan says:

The depiction on Sueno’s stone of a mighty battle, with one panel showing an arch under which lie corpses, one with a framed head, fits the list account of Dubh’s death. If the framed head is truly Dubh, then the stone would probably have been erected by his brother Cinaed II.

Cináed II was killed in 995, so Duncan implies the stone was erected in the late 10th century. While his theory has the benefit of being tied to documented local events, it hasn’t won many supporters. Instead, most historians – at least the ones who have ventured an opinion – tend to see Sueno’s Stone as a monument to Cináed I (Kenneth McAlpin), and his supposed mid-9th century conquest of Pictland.

David Sellar, for example, writes in the 1993 book Moray: Province and People:

[In 1979] I put forward the hypothesis that the Stone marked the final victory north of the Mounth by the Scots over the Picts. On this view, Sueno’s Stone would commemorate a battle which took place in the mid-9th century, although its erection need not have been exactly contemporary.

The clincher for Sellar was the stone’s depiction of decapitated heads; a feature of 9th and 10th century Irish warfare as documented in the contemporary Annals of Ulster.

In the same collection of essays, Anthony Jackson also suggests a post-843 date, albeit using methods reminiscent of a Dan Brown novel. He proposed that the entire stone was written in a numerological code designed to send an explicit message to the Picts:

I suggest that this stone was erected by Kenneth MacAlpin to tell the Picts in their own symbolic code that they were vanquished. Why should there be two execution scenes? Why are only 7 people beheaded each time? Why are groups of 4 so prevalent?

It should be noted that, by Jackson’s own admission, his theory only works if we accept that the stone has at some point been re-erected back to front – something that Occam’s razor might disallow.

One modern historian in favour of an 11th-century date is James Bruce, who, like Alexander Gordon in 1726, links the battle imagery on Sueno’s Stone to the exploits of Malcolm II. But rather than a battle at Mortlach, Bruce links the scenes to a sequence of events culminating in the Battle of Carham on Tweed in 1018.

In an April 2022 talk to the Berwick History Society, he says:

If Malcolm II had wanted a visual narration of his 13-year feud with Uhtred of Northumbria, this is more or less what it would look like. You’d have Malcolm’s inauguration in 1005, the siege of Durham [in 1006] with soldiers either side of the tower, the aftermath of the siege with the decapitated bodies, and Carham with infantry on one side and cavalry on the other.

What is a stone commemorating events in the north of England doing up in Forres? Bruce proposes that it was raised by Malcolm II to alert Macbeth (who was based in Moray before becoming king of Scotland in 1040) to the fact that he had chosen his grandson Duncan I as his successor, and to warn him not to put up any opposition.

Make of this what you will, but it does show that trying to link the imagery on the stone to known historical events can produce a multitude of different theories – none of them particularly provable.

Archaeology to the rescue (or not)

Ideally, this is the point at which archaeology would come to the rescue, providing incontrovertible dating evidence gleaned using one or more scientific techniques. But unfortunately, despite archaeologists’ best efforts, this has proven difficult.

In 1990-1991, a team of archaeologists led by Rod McCullagh undertook a major excavation around the stone, in advance of the installation of its protective glass shelter. McCullagh was aware that this was probably the last and best opportunity to obtain a date through carbon dating of organic material found at the site.

His excavation report is well worth a read (especially as regards the question of whether the stone was originally one of a pair), but the carbon dating evidence proved inconclusive.

McCullagh was only able to retrieve a few samples of charcoal from the base of pits his team found around the stone – and from these, only two carbon dates came back: one giving a high probability of a 960-1160 date range, and the other a high probability for 660-880. McCullagh concluded:

Although there is general agreement that the monument must date to between the ninth and eleventh centuries, greater precision has not been achieved and is probably not possible.

However, in 2020, archaeology MSc student Ruth Loggie managed to make slightly more headway. As part of a very well researched (and as yet unpublished) thesis on the chronology of Sueno’s Stone, she sent more of the material unearthed by McCullagh’s team to the lab for dating. Three new 91% probable date ranges came back: one for 328-418 AD, one for 1034-1168, and one for 1032-1170.

Loggie interpreted the earliest of these dates as irrelevant, and the second two as evidence of later 11th or 12th century activity around the stone. Putting all of her research together, she concluded:

The comparisons and parallels found in 8th/9th century Pictish sculptured stones and manuscript work strongly suggest that Sueno’s Stone was raised in the late 9th century and the dating of features around the stone suggests it remained significant until at least the 11th/12th centuries.

Conclusion

So what have I learned from all this? One takeaway is that the dating of Sueno’s Stone is as fraught a question as it ever was.

I don’t think I’ve missed any radical reappraisals that put it in the 8th century (although please do comment if I’ve missed something important). But I do perhaps detect a slightly stronger inclination to put it in the 9th century rather than the 10th.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t help an awful lot to pin down the ‘Pictishness’ or otherwise of the stone. The second half of the 9th century was a time of huge upheaval that led to the end of the Pictish kingdom (or kingdoms, as northern Pictland may have been a separate kingdom from southern Pictland at this time) and the birth of the Gaelic kingdom of Alba.

A date in the first half of the century would make Sueno’s Stone comfortably Pictish, while a date in the second half would perpetuate questions about whether it’s a Pictish, Scottish or hybrid Picto-Scottish monument. Establishing that can only come from understanding its precise historical and political context, and that – at least for now – is still anyone’s guess.

References

Archaeoptics Pictish Symbol Stone Database

James Bruce, Trajan’s Máel Coluim: Interpreting Sueno’s Stone (2022)

S. Driscoll, Alba: The Gaelic Kingdom of Scotland AD 800-1124 (2002)

A.A.M. Duncan, The Kingship of the Scots, Succession and Independence 842-1292 (2002)

A. Gordon, Itinerarium Septentrionale (1726)

I. Henderson and G. Henderson, The Art of the Picts (2004)

Historic Environment Scotland, Sueno’s Stone – History

L. Isaksen, The Hilltop Enclosure on Cluny Hill, Forres (2017)

R. Loggie, A Revisit to Sueno’s Stone, unpublished MSc thesis (2020)

A. Maldonado, Crucible of Nations: Scotland from Viking Age to Medieval Kingdom (2021)

R.J. McCullagh, Excavations at Sueno’s Stone, Forres, Moray (1995)

J. Mitchell, G. Noble et al, Monumental cemeteries of Pictland (2020)

A. Ritchie, Invaders of Scotland (2000)

W.D.H. Sellar, Sueno’s Stone and its Interpreters (1993)

R.B.K. Stevenson, Pictish Art, in The Problem of the Picts (1955)