An overlooked Pictish monastery in the Life of St Columba?

In which I propose that the place-name ‘caput regionis’ referred to Kinneddar in Moray

[UPDATE 28/01/25: Many thanks to those who responded to this post yesterday with a couple of counterpoints and some extra information, mainly around the position of Dunadd in the first millennium AD. Geographical modelling by Richard Lathe and David Smith in 2013 indicates that Dunadd was on an island, and later a coastal promontory, in the early Middle Ages. This greatly strengthens the case for Dunadd being a port in the sixth century, but its identification as Adomnán’s caput regionis may still be doubted, for the other reasons I’ve outlined here. I’ve added a couple of footnotes and added Lathe and Smith’s report to the bibliography.]

One of the most frustrating (or enticing) things about the early medieval Moray Firthlands is that the region is almost invisible in the surviving written sources from the period.

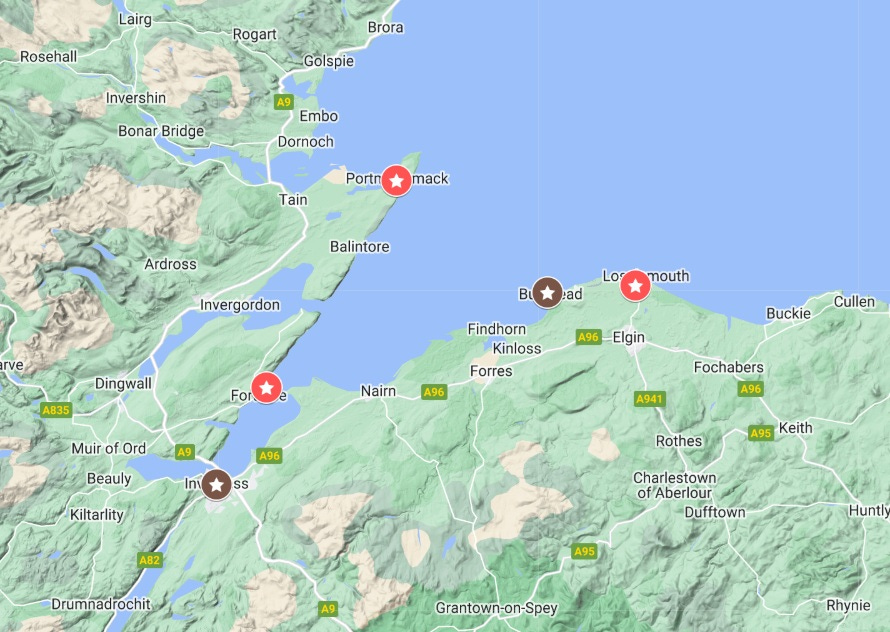

Thanks to Adomnán’s Life of St Columba, we know that Bridei son of Maelchon, King of Picts, had his stronghold somewhere near Inverness. And a handful of written words from the seventh and ninth centuries suggest that a seventh-century bishop, Curetán, very likely had his see at Rosemarkie on the Black Isle.

But if it wasn’t for archaeology, we would never know that Burghead was one of the largest fortified sites in Pictland, or that Portmahomack was a major monastery producing illuminated manuscripts and exquisite sculpture. Likewise the monastery at Kinneddar, whose enclosing vallum (bank and ditch) is the same size and shape as Iona, is entirely missing from the records.

A tiny clue from the Life of St Columba?

This extreme lack of sources means I’m continually on the lookout for tiny scraps of information about the early medieval Firthlands that might have been overlooked.

This blog is about one of those scraps—a place-name in Adomnán’s Life of St Columba (hereafter the Life) that has never been satisfactorily identified.

Adomnán gives its name in Latin as caput regionis (roughly ‘chief-place of the district’), and I want to propose that it refers to the monastery of Kinneddar near Burghead in Moray.

Come along with me as I examine the case for and against this rather left-field interpretation.

The context of caput regionis

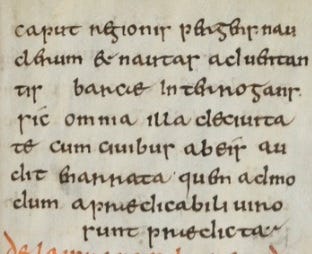

First let’s look at how caput regionis appears in Adomnán’s text, which he wrote around 700 AD. It’s only mentioned once, in book I, chapter 28. Like most chapters of the Life, it’s pretty short, and deals with one of the miracles performed by Columba during his lifetime.

In it, Columba has a premonition of a disaster that has struck a town in Italy. One of the monks of Iona, Luigbe moccu Min (more of him later), finds the holy man red-faced in anguish, and asks what is troubling him. Columba replies (in Alan and Marjorie Anderson’s 1961 translation):

In this hour, sulphurous flame has been poured down from heaven upon a city of the Roman dominion within the borders of Italy; close upon three thousand men, not counting the number of women and children, have perished. Before the present year is ended, Gallic sailors arriving from the provinces of Gaul will tell you the same.

Columba’s powers of foresight are then shown to be accurate, with the chapter concluding:

After some months, these words were proved to have been correct. For Lugbe went, along with the holy man, to caput regionis; and he questioned the master and sailors of a ship that arrived, and heard those things about the city and its inhabitants related by them, all precisely as the memorable man had said before.

A glimpse of early medieval European trade networks

This chapter has attracted much attention from historians and archaeologists, as it provides a glimpse of international connections and trade routes in mid-first-millennium northern Britain.

Here, seemingly, is proof, at least from around 700 when Adomnán was writing, that merchants from Gaul (France) were active in the western seaways of northern Britain.

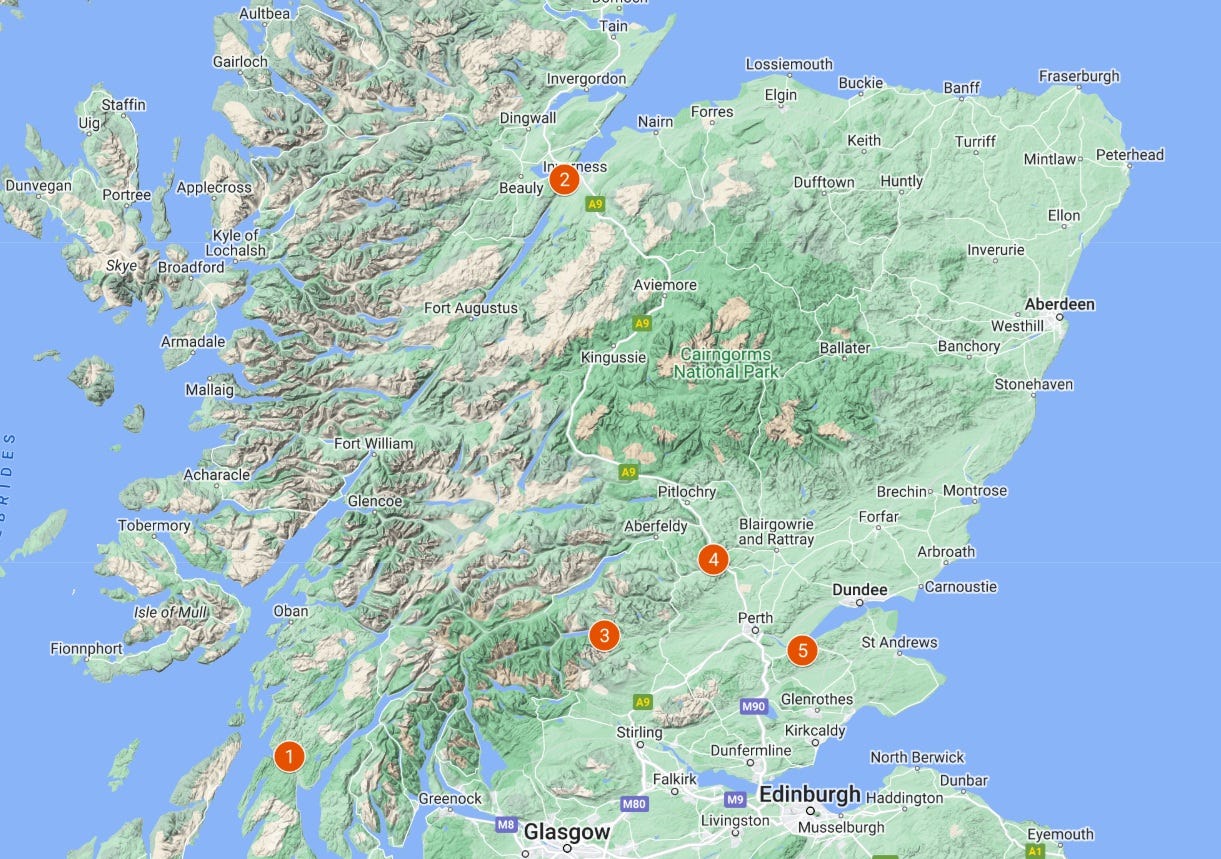

This provides valuable historical corroboration for the imported pottery and glass that shows up at elite secular sites like the fortress of Dunadd in Argyll and the hillforts of Craig Phadrig near Inverness and Dundurn in Perthshire.

The only problem is that it’s hard to pin down exactly where Adomnán meant by caput regionis. Historians, archaeologists and place-name specialists have all attempted to interpret it, with some focusing primarily on its meaning in Latin, and others focusing on its context in the Life. Three candidates have emerged from these analyses: Kintyre, Dunadd and Dunollie.

All three of these places are in Argyll, which in the mid-first-millennium was the Gaelic-speaking kingdom of Dál Riata, in which the island monastery of Iona also lay.

However, as we’ll see, caput regionis need not have been in Dál Riata, and an assumption that it was in Iona’s home territory may have prevented historians from considering other candidates.

The case for Kintyre

So to Kintyre first of all. In 1857, William Reeves published a heavily-annotated edition of the Life. In it, he noted that the name caput regionis was similar to a description used by the sixteenth-century scholar George Buchanan for the peninsula of Kintyre.

In his Rerum Scoticarum Historia of 1582, Buchanan wrote (his Latin with my translation):

Ultra Cnapdaliam ad occidentem hibernum excurrit Cantiera, hoc est, regionis caput.

Beyond Knapdale to the south-west extends Kintyre, which means head of the region.

Since Kintyre often appears under its Gaelic name of Ceann-tíre (literally ‘head of the land’) in Irish monastic annals, which were contemporary with the Life, Reeves felt it must be the place Adomnán meant by caput regionis.

Reeves was followed in this assessment by the place-name scholar William J. Watson. In his 1926 Celtic Place-Names of Scotland, Watson wrote:

Kintyre is in Adamnan caput regionis, a literal translation of Ceann Tire. It is one of the names most commonly mentioned in Irish records.

Two other possibilities: Dunollie and Dunadd

However, in 1961, Alan and Marjorie Anderson produced a new edition and translation of the Life, in which they pointed out the flaw in this interpretation of caput regionis:

Caput regionis is ‘chief place of the region’ rather than a translation of cenn tire (Kintyre), the expected translation of which would be caput terrae.

In other words, the tír of Kintyre means land as in ‘landmass’, not land as in ‘administrative region’.1 It’s the place where the mainland of Argyll meets the North Channel.

In their introduction, the Andersons offered two alternative interpretations. Assuming that regionis referred to Columba’s local region, the kingdom of Dál Riata, they proposed two fortified sites considered to have been ‘chief-places’ of two leading kindreds of Dál Riata:

Columba was on terms of friendship with the king [of Dál Riata,] Áidán son of Gabrán… We hear of him also at caput regionis when a ship arrived there from Gaul. Dunollie, above the north end of Oban Bay, was perhaps the caput of Lorn; but there is material evidence for Dunadd as the caput of the Cenél nGabráin, or of the Dál Riata in general.

The problems with Dunollie and Dunadd

In suggesting both Dunollie and Dunadd, the Andersons hint at—but don’t explicitly acknowledge—the problems with these two interpretations of caput regionis.

As they say, Columba was on close terms with Cenél nGabráin (the kindred of Gabrán); indeed he had inaugurated Áidán as king of Dál Riata. Cenél Loairn, the other Dál Riatan royal kindred, features less in the Life, perhaps precisely because Iona’s patrons were Cenél nGabráin.

If Columba was going to visit a ‘chief-place’ of Dál Riata, then, it was much more likely to be the stronghold of Cenél nGabrain, widely believed to have been at Dunadd. But the Andersons’ first suggestion is Dunollie, usually considered to have been the main stronghold of Cenél Loairn.

The unspoken difficulty is that caput regionis is evidently a port or harbour. Columba and Luigbe don’t just meet Gallic traders there—they also meet the ship’s captain, implying that the ship was docked there. But the rock fortress of Dunadd is (at least, today) around two miles inland, accessible from the sea-loch of Crinan via the River Add, but only in a small boat.2

Dunollie, by contrast, is on the coast, on a rocky outcrop above Port Mór, a small bay that would have made a good landing-place. Its location fits Adomnán’s story much better, but Dunollie is in the district of Lorn, home to Cenél Loairn.

So for Adomnán to call Dunollie caput regionis, if he meant by this the chief-place of Dál Riata, would be very odd, particularly since he gives no other indication of which place he means.

Why Dunadd remains the front-runner

Despite the fact that Dunadd is inland,3 it remains the front-runner among historians and archaeologists for the location of caput regionis. This is largely based on two things.

First is the assumption that by regionis Adomnán meant the region local to Iona, i.e. Dál Riata. Secondly, a wealth of imported material found at Dunadd points to trade links with Gaul, increasing the likelihood that Columba and Luigbe might have encountered Gallic sailors there.

As an example of the first, we can look at Richard Sharpe’s 1995 edition and translation of the Life for Penguin Classics. He footnotes caput regionis thus:

Caput regionis must, as the Andersons observed, mean ‘the capital of the district’. Caput is used in this sense by Adomnán’s contemporary Muirchú, who describes Tara as caput Scottorum ‘capital of the Irish’. Regio is often a difficult word to interpret, but I should take it here to mean the whole region of Scottish Dalriada.

Like the Andersons, then, Sharpe assumes that the regio in question is Dál Riata. In fact he is so instinctively sure of it that he allows it to subtly influence his translation of the chapter. In Adomnán’s original Latin, Columba says to Luigbe:

Et antequam praesens finiatur annus, Gallici nautae, de Galliarum provinciis adventantes, haec eadem tibi enarrabunt.

Sharpe translates this as:

Before this year ends you will hear news of this [i.e. the volcanic eruption in Italy] from Gallic sailors arriving here from Gaul.

Columba and Luigbe are in the monastery of Iona when this exchange takes place, so when Sharpe writes “arriving here from Gaul” he implies arriving in Iona, or at least Dál Riata.

But there is no indication in Adomnán’s text that Columba foresees the sailors coming to Dál Riata specifically. The word in question is adventantes, which just means ‘arriving’. A more literal translation would be:

Before this year is ended, Gallic sailors, arriving from the provinces of Gaul, will relate this same [news] to you.

So in Adomnán’s text, caput regionis doesn’t have to be in Dál Riata. It’s just the place where Luigbe will be when sailors from Gaul arrive. As we will see, Luigbe is shown travelling in other chapters, so in principle it’s no problem to think he might meet a ship’s crew somewhere else.

The pottery assemblage from Dunadd

However, there is the evidence of the archaeology at Dunadd, where a substantial amount of imported E ware pottery has been found. A link between this pottery and the location of caput regionis was made in a 1987 article by the archaeologist Ewan Campbell, who wrote:

Adomnán relates a story about Colum Cille visiting the ‘caput regionis’ where he meets Gallic merchants. This place has been taken to refer to Dunadd (Anderson and Anderson 1961, 39). The large amounts of imported material found there, including E ware produced in France, would seem to be very strong circumstantial evidence to support this claim.

Despite this, Campbell wasn’t fully comfortable with the interpretation of caput regionis as Dunadd, noting that Adomnán is usually quite precise about place-names:

The name is surprisingly imprecise if it does refer to Dunadd, given that Adomnán often mentions the names of places, even when referring to small bays and other natural features.

Indeed, the presence of E ware at Dunadd doesn’t automatically make it the unquestionable candidate for caput regionis. E ware has also been found at other sites in Scotland, including Craig Phadrig near Inverness, Clatchard Craig in Fife and Dundurn in Perthshire, all of which were in Pictland.

Archaeologists initially thought that the imported material reached these Pictish sites as diplomatic gifts from Dál Riata or Strathclyde, rather than via direct trade with Gaul. But the discovery in 2019 of a large collection of E ware and vessel glass at King’s Seat near Dunkeld has put a different complexion on our understanding of trade links in early medieval Scotland.

The Scottish Archaeology Research Framework says that:

When only the material from Dundurn was known, it was seen as an outlier to trade which came up the west coast of Britain and then inland from Dál Riata and Strathclyde. However, these latest discoveries push the find spots further east and suggest that it is time to look again at the question of trade transported from the east coast.

So it is at least conceivable that Columba and Luigbe might have come across Gallic merchants in the Pictish east as well as in Gaelic Dál Riata.

Adomnán’s treatment of place-names

Crucially, Ewan Campbell observed something else about Adomnán’s use of place-names, which could be the smoking gun for caput regionis. He wrote:

…[E]lsewhere, Adomnán translates place-names directly into the Latin equivalent, for example campus Lunge for Mag Lunge.

In fact, the Iona place-name specialist Gilbert Márkus has shown that Adomnán was attuned to the meanings of names, and actively enjoyed translating personal names and place-names into their Latin equivalents.

As Campbell noted. Adomnán uses the Latin name campus Lunge to denote Mag Lunge (‘ship-field’), a daughter-house of Iona located on the island of Tiree. It appears as campo Lunge in I.30 and I.42, campi Lunge in II.15, and monasterium campi Lunge in II.39 and II.40.

Another daughter-monastery of Iona was Durrow in County Laois. While Adomnán gives it its Irish name of Dairmag (‘oak-field’) in I.3, he refers to it thereafter in Latin: as roboreti campi in I.29, roboreti monasterium campi in I.49, monasterium roboris campi in II.2, monasterium roborei campi in II.39, and roboreti campo in III.15, from Latin roboreus meaning oak or oaken.

So while Adomnán doesn’t always translate place-names into their Latin equivalents, he often does so—and does so carefully—for monasteries. What’s more, he sometimes uses the Latin name without specifying that it is a monastery.

Is it possible, then, that caput regionis isn’t a ‘surprisingly imprecise’ way of referring to Dunadd, but a precise rendering into Latin of a monastery whose name literally meant ‘chief-place of the region’?

The case for Kinneddar

The monastery I have in mind is Kinneddar in Moray, which I first wrote about here. Although there’s nothing much to see there today, there are strong signs that it was a large and important monastic site in the early Middle Ages.

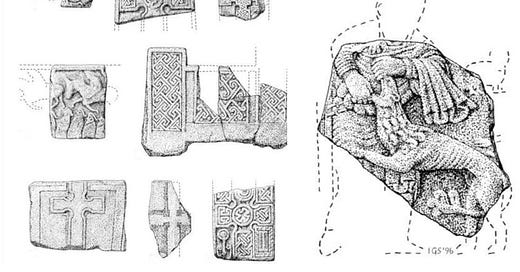

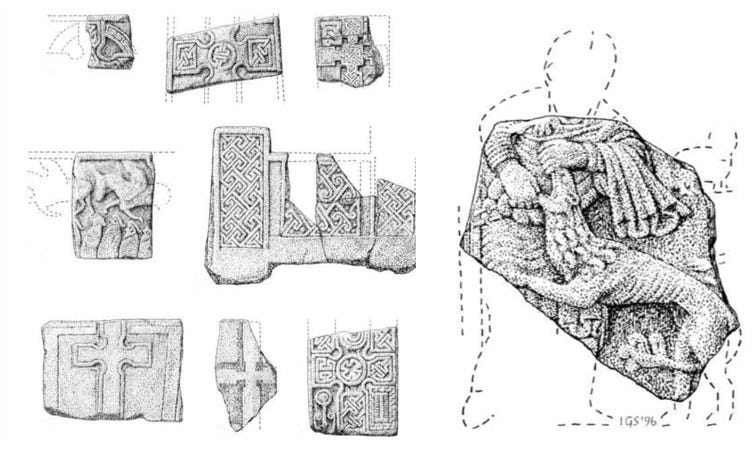

This is evidenced by a large collection of high-quality early medieval sculpture from the site, which includes evidence of royal patronage in the form of a fragment of a shrine or cross-slab depicting the biblical King David, whom art-historians see as an icon of kingship in Pictish art.

In 2017 the University of Aberdeen and AOC Archaeology excavated the vallum at Kinneddar and wrote it up for the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. This is what they said about its name, drawing on information from the place-name specialist Dr Simon Taylor:

The place-name of Kinneddar derives from Gaelic cenn, ‘head, end’ (either in terms of promontory or a chief-place), plus foithir, probably derived from a Pictish word meaning something like ‘district, region’, thus it means ‘end of the district’.

‘End of the district’ might be one way of rendering the name in English, but another might be ‘chief-place of the region’, the exact English translation of caput regionis.

So could Kinneddar be the place where Columba and Luigbe moccu Min met the Gallic sailors, and heard news of the volcanic eruption in Italy that Columba had miraculously foreseen?

I think it could, for three further reasons.

1. The harbour of Loch Spynie

Firstly, like Dunollie, Kinneddar lay on a harbour. Today the site lies on the fertile arable plain of the Laich of Moray, but in the early Middle Ages, it lay on the shore of the sea-loch of Spynie.

This loch was progressively drained from the twelfth century to create valuable farmland, culminating in a huge drainage effort in the eighteenth century. It is, however, visible in reduced form on early maps of Moray by Timothy Pont (c.1590) and Robert Gordon (c.1645).

As it originally had an opening to the sea where the town of Lossiemouth now stands, Loch Spynie would have offered a sheltered harbour for ships navigating the east coast of Pictland.

And, as we saw above, archaeologists are now rethinking trade routes in early medieval Scotland, to embrace the possibility that imports did arrive directly into Pictland from Gaul.

2. The presence of Luigbe moccu Min

Secondly, and a little more complicatedly, there’s the fact that Columba met the Gallic sailors in the company of Luigbe moccu Min.

Luigbe is an Iona monk who features in three chapters of Book I of the Life. As well as accompanying Columba to caput regionis in I.28, he appears in I.15 on a diplomatic mission from King Rhydderch ap Tudwal of Alt Clut (Strathclyde), and in I.24 he features—somewhat more prosaically—accidentally dropping a book into a jug of water.

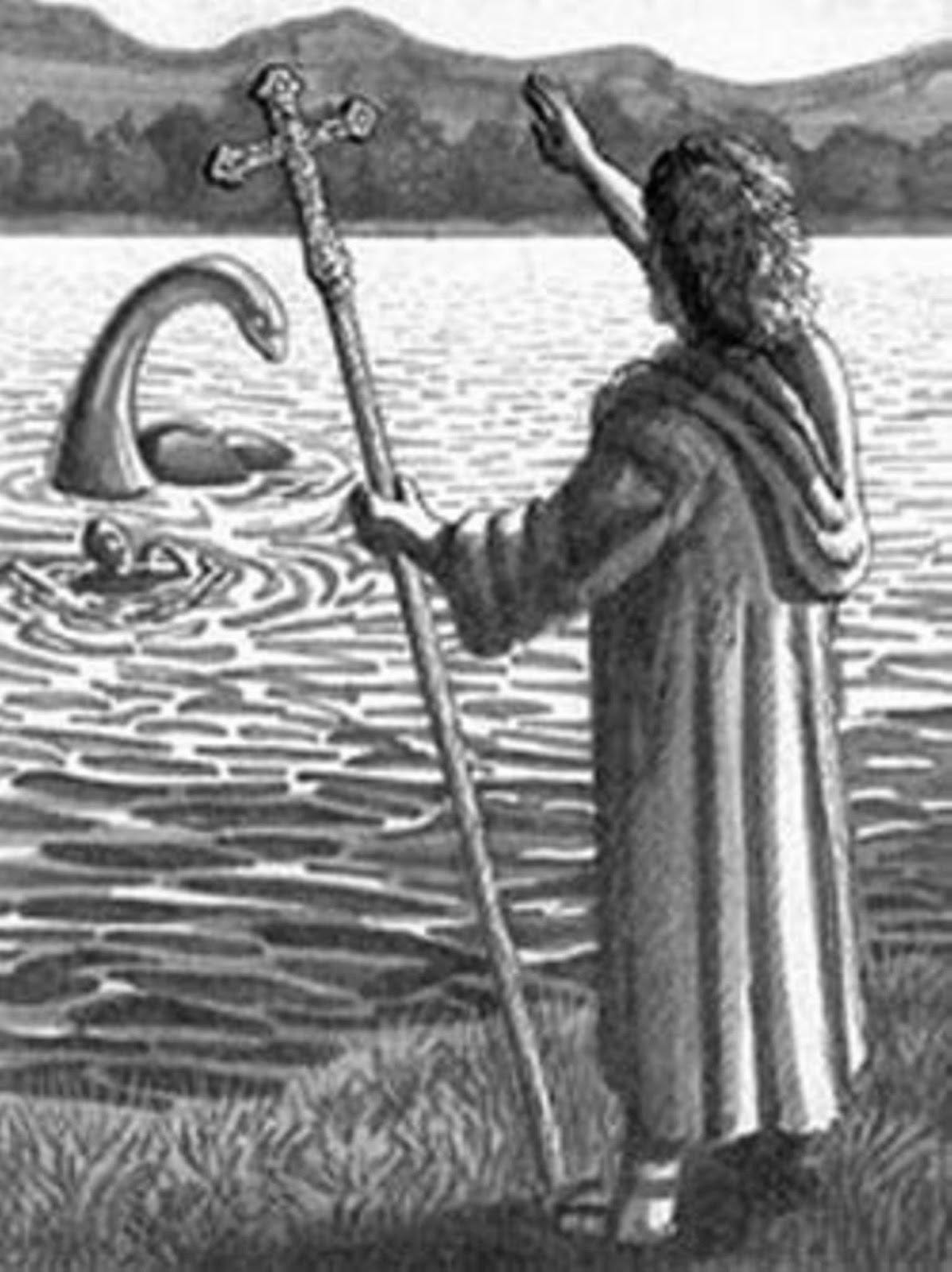

A monk with almost the same name, Luigne moccu Min, appears in two chapters of Book II. I’ve written about Luigne recently—he’s one of a group of monks who accompany Columba to the court of King Bridei son of Maelchon on the River Ness. In fact it’s poor Luigne whom Columba sends into the river in II.27 as bait for the famous water-beast.

The water-beast episode places both Columba and Luigne in the Moray Firthlands, and it’s not too much of a stretch to think they might have visited Kinneddar while they were there. The chapters in the Life aren’t in chronological order, so a visit to Kinneddar mentioned in Book I could have taken place at the same time as one of the visits to Bridei’s fort in Book II.

The only problem is that it’s Luigbe, not Luigne, who goes to caput regionis with Columba. However, some Adomnán scholars, including Máire Herbert and Pádraig Ó Riain, think they’re the same person, especially since Luigbe only appears in Book I and Luigne only appears in Book II. If they are the same person, it strengthens the case for caput regionis being Kinneddar.

3. Archaeological evidence from Kinneddar

Lastly, there’s the evidence of the Kinneddar site itself. To date, only its vallum ditch has been investigated archaeologically, but the findings of that exploration were quite remarkable. The excavation report noted that:

The vallum enclosed an extensive area that is likely to have been around 8.6ha… [T]he radiocarbon dating evidence suggests activity… as early as the late 6th century and certainly by the 7th century, with the primary vallum ditch dug sometime after cal AD 600–680.

Not only was Kinneddar conceivably in existence during Columba’s lifetime (he died in 597), it also had striking physical similarities to Columba’s own monastery:

The nearest parallel in terms of form and scale to Kinneddar is Iona, which was enclosed with a very similar sub-rectangular series of vallum ditches… The dates for the vallums at each site are also broadly similar.

Based on this evidence, the archaeologists floated a possible relationship between the two monasteries:

The structure and dating parallels between the enclosure at Kinneddar and those at Iona are intriguing and perhaps suggest very direct connections between the Columban Church and the establishment of Kinneddar.

Conclusion: A name familiar to Adomnán’s audience?

Could a glimpse of those connections be hiding in plain sight in the place-name caput regionis?

On a recent episode of the Medieval Irish History Podcast, my PhD co-supervisor Professor Thomas Clancy talked about who Adomnán was actually writing the Life for:

It’s definitely for his own community… the monastery of Iona or the wider Columban federation. The names he’s using mean something to this primary audience.

My takeaway from this is that when Adomnán uses Latin versions of the names of monasteries, these are names that the Columban community would recognise as other monasteries—either in Iona’s network of daughter-houses, or with which Iona had regular dealings.

Like campus Lunge or roboris campo, then, we might imagine readers of the Life instantly recognising caput regionis as the name of such a monastery—and my rather nerve-wracking proposal is that it was the monastery of Kinneddar in the province of Moray in northern Pictland.

Postscript

As a short postscript, in II.46 of the Life, Adomnán provides a direct insight into his own time when he writes of a plague that has recently beset the islands of Ireland and Britain. He says:

Everywhere was affected, apart from two peoples: the population of Pictland and the Irish who lived in [Dál Riata].

He puts this miraculous escape down to the posthumous protection of Columba:

Surely this grace from God can only be attributed to St Columba? For he founded among both peoples the monasteries where today he is still honoured on both sides.

In a plaintive footnote to this statement, Richard Sharpe commented:

One could wish that Adomnán had named the monasteries that St Columba had founded in Pictland and Scottish Dalriada.

In Adomnán’s fleeting mention of caput regionis, it’s just possible that he did at least name one.

References

Anderson, Alan and Marjorie Anderson (eds. and trs.). Adomnán’s Life of Columba. Oxford University Press (1961)

Campbell, Ewan. ‘A cross-marked quern from Dunadd.’ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 117, 105–117 (1987)

Herbert, Máire. Iona, Kells, and Derry: The History and Hagiography of The Monastic Familia of Columba. Oxford University Press (1988)

Lathe, Richard, and David Smith. ‘Holocene relative sea-level changes in Western Scotland: the early insular situation of Dun Add (Kintyre) and Dumbarton Rock (Strathclyde)’. The Heroic Age: A Journal of Early Medieval North-West Europe 16 (2015): 1-12.

Márkus, Gilbert. ‘Latin and Gaelic in the early monastery: detecting a dialect-shift?’ Blog post for Iona’s Namescape (2020)

Noble, Gordon, Gemma Cruickshanks, Lindsay Dunbar, et al. ‘Kinneddar: a major ecclesiastical centre of the Picts.’ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 148: 113–145 (2019)

Reeves, William (ed.) The Life of St Columba, founder of Hy; written by Adamnan, ninth Abbot of that Monastery, edited from an 8th-century codex. Dublin University Press for the Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society (1857)

Sharpe, Richard (ed. and tr.). Life of St Columba by Adomnán of Iona. Penguin Classics (1995)

Many thanks to Thomas Clancy and Fergus Holmes-Stanley for their observations that contrary to the Andersons’ view, tír is sometimes used in the early Middle Ages to denote a political territory as well as a landmass. An obvious example is the name Tír Eoghain (Tyrone) to denote the territory of the Cenél nEógain branch of the Uí Néill dynasty. This perhaps puts Kintyre back into the running for the location of caput regionis, although we might have to explain what Columba, Luigbe moccu Min and the Gallic merchants were doing there.

In fact, sea-level change modelling by Richard Lathe and David Smith in 2013 found indications that “when the fortification [at Dunadd] was first constructed (circa 300 BC) the outcrop was largely surrounded by the sea, and [it] retained promontory or island status as late as AD 460–770.” I have added the report to the bibliography.

See footnote 2 above.