In civitate Nrurím: A medieval place-name mystery

In which I examine three theories about where king Áed mac Cináeda died in 878 AD

878 AD was a momentous year in British politics. It was the year in which Alfred defeated Guthrum’s Great Heathen Army at Edington in Wiltshire, resulting in the carving-up of middle and southern England into Wessex in the west and the Danelaw in the east. A turning point for Alfred, it set the house of Wessex off on a multi-generational project to build the country we still know as England.

In the country we now know as Scotland, however, Alfred’s contemporary Áed mac Cináeda wasn’t having as much luck. Having succeeded his brother Constantín to the kingship of the Picts only the previous year, his reign came to an almost immediate end when he was murdered in 878.

The mystery of where Áed was killed

Unfortunately for Áed, that is almost everything we know about him. Whereas Alfred’s exploits were preserved for posterity by his biographer Asser and others, all we know about Áed is contained in a few brief notes and annals. But as terse as these dispatches are, they still contain enough puzzling information to keep historians arguing, guessing, and coming up with elaborate theories.

For this blog, I’m looking at one aspect of those theories: the place where Áed was killed. I’m looking at it because it involves an unidentified place-name, and unidentified place-names are like catnip to early medievalists. But it also tells us quite a lot about manuscripts, and manuscript studies, and the immense challenges that come with that field. And since I’m just starting to learn about manuscripts and medieval handwriting on my MA course, it ties in nicely with what I’m doing there.

Áed’s death in the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba

To see what the issue is, we have to look at how Áed’s death was recorded in one of the earliest sources for the history of ninth-century Scotland.

The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba (CKA) is a short text that recounts the names and reign lengths of the earliest Scottish kings, along with some notable events that happened during their reign.

It lists twelve kings, starting with Cináed mac Ailpín (Kenneth McAlpin) in 842 AD and ending with the Cináed mac Maíl Coluim (Kenneth II) in 995 AD. Its original version was compiled probably somewhere in central Scotland, probably in the late tenth or early eleventh century.

When it comes to the death of Áed, CKA notes:

Edus tenuít idem .i. anno en. eciam brevitas .l’. istorie memorie commandavit set in cívítate Nrurím est occisus. [my emphasis]

Áed held the kingship for one year. His short reign has bequeathed nothing memorable to history but he was killed in the civitas of Nrurím. [my emphasis]

And it’s this weird-sounding place-name, Nrurím, that’s been the subject of multiple theories. For this blog, I’ve picked the three theories I’m aware of, and tried to break them down to see how plausible they are.

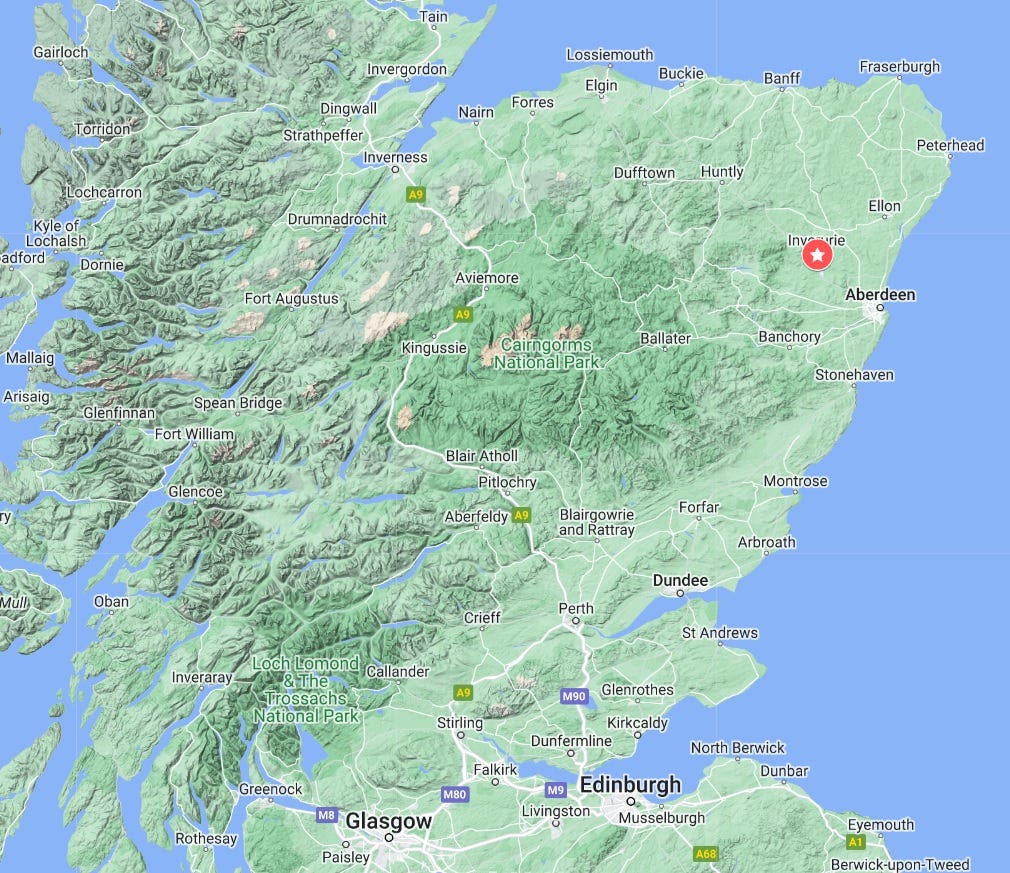

Theory #1: Nrurím was Inverurie in Aberdeenshire

So to the first theory. In his three-volume history of Scotland, Caledonia, published in 1807, the antiquarian George Chalmers associates Nrurím with Inverurie in Aberdeenshire:

It was [Áed’s] misfortune to reign, while Girig was Maormor of the extensive country, between Dee and Spey. This artful chieftain found no difficulty, to raise up a competitor, with a faction, to oppose the king. The contending parties met in Strathalan, on a bloody field, wherein the son of the great Kenneth was wounded; and being carried to Inverurie, he died two months after this fatal conflict, and one year after his sad accession, during wretched times, in 881 AD.

Chalmers seems to have stitched this narrative together from a variety of sources.1 One is CKA, with its mention of Nrurím. Another is a twelfth-century list of early Scottish kings, which says:

Edh macKynnath i a. reg. et interfectus in bello in Strathalun a Girg f. Dungal et sepultus est in Iona insula.

Áed son of Kenneth reigned for one year and was killed in battle in Strathallan by Girg son of Dungal and was buried on Iona.

Chalmers merges these two accounts to propose that Áed was wounded in a battle with Giric son of Dúngal in Strathallan in Perthshire, then taken to Inverurie, where he died of his wounds. But since the main power centre of the McAlpin kin-group was at Forteviot, relatively close to Strathallan, this seems an odd choice of refuge. What justification is there for identifying Nrurím with Inverurie?

As far as I can tell from one of his footnotes, Chalmers based his theory purely on the similarity of the two names:

The Chron. in the Reg. of St. Andrews, and the Chron. Elegiacum, state, that he was slain, in the battle of Strathalan: The Chron., No. 3, in Innes, states his death, in Nrurin.2 The fact appears to be that he was wounded in the battle of Strathalan, and died two months after, at Inverurie.

How plausible is it?

It is true that -rurim is similar to the final five letters of Inverurie. But the name Inverurie breaks into two elements: inver-, Gaelic for ‘mouth’ or ‘confluence’, and -urie, referring to the River Urie that converges with the River Don just south of the town.

It has had this form since at least 1178, when it appears in charters as Inuerurin and Inuerowry. Given that the name refers to the immutable landscape setting, it seems unlikely that it would have had a different name in the tenth century.

So if Nrurím was Inverurie, it would mean that at some point, a scribe copying out the text of CKA had decided to write Inuer- simply as Nr-. If deliberate, this seems an extreme abbreviation, especially as it doesn’t contain the initial letter I. So, absent any other supporting evidence for Nrurím being Inverurie, this theory doesn’t seem to me to be particularly plausible.

Theory #2: Nrurím was Rossie in Angus

Scribal error is also at the core of the second theory, put forward in 1998 by historian Professor Benjamin T. Hudson. In an article for the Scottish Historical Review about the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, he argued that Nrurím is actually Rossie in Perthshire, 15km west of Dundee.

Hudson makes a series of mental leaps to arrive at this conclusion, based largely on his knowledge of the way manuscripts were copied and preserved in the middle ages. The original version of CKA is thought to have been compiled in the late tenth century, but the only version that survives today—and the version on which these theories are based—is a much later copy, made in the fourteenth century.

In the intervening four centuries, as the manuscript was copied and recopied, new information was probably added, and misreadings, misspellings and other errors almost certainly crept in. Hudson makes several assumptions about these emendations to argue for Rossie as the location.

First, he draws our attention to the Latin word civitate that appears in the phrase in civitate Nrurím. He suggests this word might once have been a marginal ‘gloss’ (the medieval version of a comment on a Microsoft Word or Google Doc) that only got folded into the body copy at a later point:

Civitas is commonly used to identify a monastery in medieval chronicles; in this instance it might have been an explanatory gloss which was incorporated into the text.

Having removed civitate from in civitate Nrurím, Hudson is free to make his second supposition:

The original could have been i rRusím, with the preposition i causing gemination of the following r…

I’m not going to pretend I know why a preposition i would have to be followed by a double r, especially not a lowercase r followed by an uppercase one. But in any case, i rRusím (‘at Rossie’) is not the same as Nrurím. However, Hudson then adds a third supposition:

…which was corrupted to i nrurím.

So a scribe making a copy of CKA—presumably while civitate was still a gloss in the margin—might have accidentally transcribed i rRusim as i nrurím, and this error was perpetuated in later copies, including the lone surviving one.

How might this mistake have happened? Hudson offers a speculative explanation based on his knowledge of palaeography, the art of deciphering medieval handwriting:

An original text written in insular script would explain the confusion of n- and -s- with r- and -r-. The first of the double rs might have been written in shortened form leading to the confusion with n or it could have been originally a long r for which the descender was damaged giving the appearance of an n to a twelfth-century scribe unfamiliar with Gaelic. Similarly an original long s can easily be misread as a long r.

To show what Hudson means, above is a page from the Gospel of Matthew in the tenth-century Book of Deer, written in an insular script that is likely similar to the script used in the original of CKA.

The Latin words angelus (‘angel’) and apparuit (‘appeared’) are underlined in red. Note the long-tailed s on the end of angelus, which Hudson argues could be confused with an r, and the r in apparuit which he argues could be confused for an n.

Essentially Hudson is asking us to believe that the scribe, copying i rRusím, was unfamiliar both with the place-name and with insular script, and thus mistook the first r for an n and the s for an r, writing the name as Nrurím.

For reasons too complex to try to pick apart here, he also asks us to believe that the scribe who introduced this error was working in the twelfth century, and that they were a Norman French speaker who was unfamiliar with Gaelic.

How plausible is it?

All of Hudson’s suppositions may be true, but Occam’s razor applies: it takes a lot of leaps of faith to believe that the place intended was Rossie. It feels to me as though Hudson really wants Nrurím to have been Rossie, and is bending over backwards to find an explanation for how it could be.

I find this a bit odd as he doesn’t then try to explain why Rossie was a likely place for Áed to have died. But as I haven’t read a lot of his work, it may be an argument he makes elsewhere.

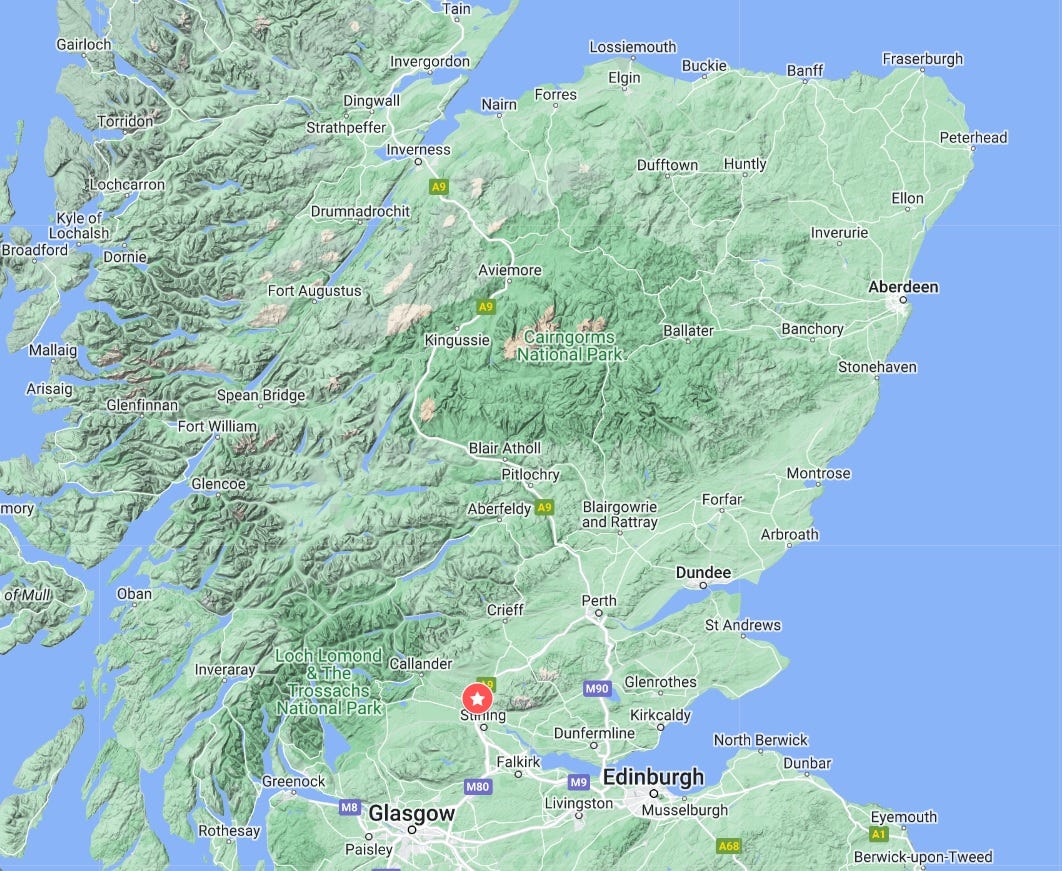

Theory #3: Nrurím was Dunblane in Stirlingshire

No doubt mindful of Occam’s razor, in 2007 Dr Alex Woolf proposed a simpler solution: that civitas Nrurím was in fact Dunblane, just north of Stirling.

Woolf is primarily a historian not a palaeographer, so his theory is based on what else we know—or can reasonably infer—about the events surrounding Áed’s death. For that, he draws on the same twelfth-century king-list as used by Chalmers, which says:

Áed son of Kenneth reigned for one year and was killed in battle in Strathallan by Girg son of Dungal and was buried on Iona.

Not all of the information contained in these king-lists is reliable, and when it contradicts what’s written in earlier sources, historians often dismiss it in favour of the earlier account. The king-lists, for example, say that three kings of Alba died in Forres, but as earlier sources say two of them were killed elsewhere, historians tend to see the insertion of Forres as later, anti-Moravian propaganda.

The same could be true here. The king-lists say Áed was killed in Strathallan, but CKA, the earlier and therefore theoretically more reliable source, says he was killed in Nrurím. However, Woolf says there may be no contradiction: Nrurím could be a place in Strathallan, specifically Dunblane.

His argument rests on two things: the word civitas and the etymology of Dunblane. First he says:

The twelfth-century king-lists say that [Áed] was killed in battle in Strathallan by Girig son of Dúngal. The value of this is uncertain, but as far as we know there was only one civitas in Strathallan, if civitas here means major church-settlement, and that is Dunblane.

But the name Dunblane—or Dol Blááin (‘meadow of St Blane’) as it was in the early middle ages—is nothing like Nrurím. This couldn’t possibly be a copying error. Instead, Woolf argues that Nrurím may have been an earlier name for the settlement, before the relics of St Blane were moved to it:

If Blane’s relics had only been transferred to Strathallan in the recent past, it is possible that an older name for the church there survived (one might compare St Asaph’s, the English-language name for Llanelwy, the episcopal centre of northeast Wales, or indeed St Andrews for Rigmonaid).

How plausible is it?

At first I thought this was a neat and convincing argument, but now I’m not so sure. Firstly, this isn’t the only time Dunblane appears in CKA. It also appears in an account of the reign of Áed’s grandfather Cináed mac Ailpín—but there, it’s written as Dulblaan:

Britanní autem concremaverunt Dulblaan atque Danari vastaverunt Pictaviam ad Cluanan et Duncalden.

The Britons burned Dunblane and the Danes devastated Pictavia as far as Clunie and Dunkeld.

It seems at least questionable that the place would be given its ‘new’ name at the start of the chronicle, and then its ‘old’ name just a few lines later.

Secondly, both Llanelwy and Rigmonaid make sense in their respective languages: Brittonic (Welsh) and Gaelic. Llanelwy means church on the river Elwy, and Rigmonaid means the king’s hill.

Nrurím doesn’t seem to contain any known Gaelic or Brittonic place-name elements, which is partly why it continues to be so puzzling. So I think Woolf’s theory might need a further consideration of whether this was actually the original place-name, or whether it is a corruption of the original name.

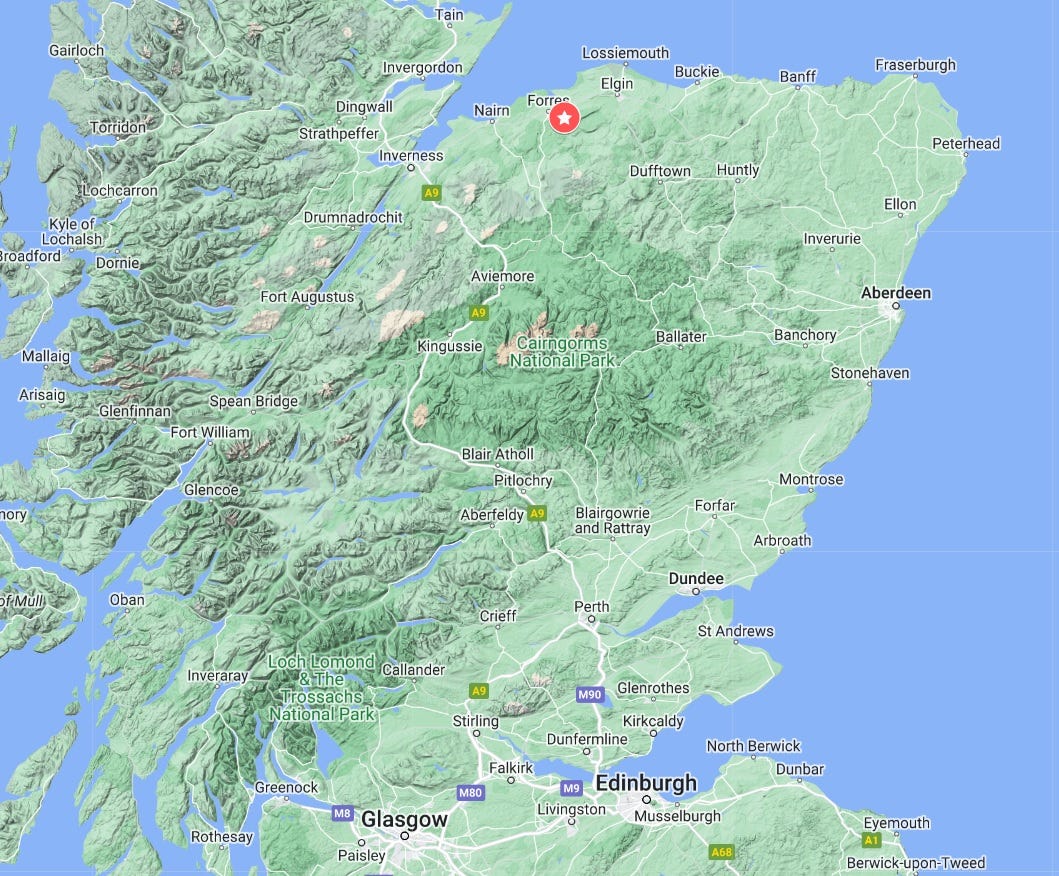

Theory #4: Nrurím was Blervie near Forres

On the grounds that all three of the above theories are at best slightly shaky, maybe I can be permitted to throw my own shaky theory into the mix: that Nrurím was Blervie, near Forres.

One person who was extremely familiar with the actual manuscript in which the name Nrurím appears was Dr Marjorie Ogilvie Anderson, a palaeographer and manuscript historian. Her 1973 book Kings and Kingship in Early Scotland offers an exceptionally methodical analysis of the texts of CKA, the king-lists and other early sources of Scottish history.

Anderson analysed the handwriting of every word of CKA, and concluded that Nrurím wasn’t the only reading that could be produced from that particular series of letters. In a footnote, she adds:

Just possibly uturím.

On reading this, something pinged in my brain. Another odd-sounding place-name that appears in some versions of the king-list is variously written as Ulurn, Ulnem, Ulum and Ulrum. All of these spellings denote the place where the lists say king Malcolm mac Domnaill was killed in 954 AD.

The ‘F’ version of the king-list says:

Malcolm Mac-Dovenald 9 an interfectus est in Ulurn a Moraviensib. sep in Iona.

Malcolm son of Donald [reigned for] 9 years, was killed in Ulurn by the Moravians and was buried on Iona.

While the ‘I’ version has:

Malcolm filius Dounald .ix. annis et interfectus est in Ulnem a Moraviensibus per dolum et sepultus in [Ioua insula].

Malcolm son of Donald [reigned for] 9 years and was killed in Ulnem by the Moravians through treachery and was buried on Iona.

And a version of the king-list that was inserted into two different versions of the Chronicle of Melrose says (in English as I don’t have access to the original Latin):

Version A: “The men of Moray slew him in Ulum.”

Version B: “The men of Moray slew him in Ulrum.”

It doesn’t take too big a leap of faith to think that CKA’s uturím (if that is the correct reading) could be a further (mis)spelling of this same name. Ulrum in particular isn’t a million miles from uturím, though I’m quite prepared to be put right on why it couldn’t be.

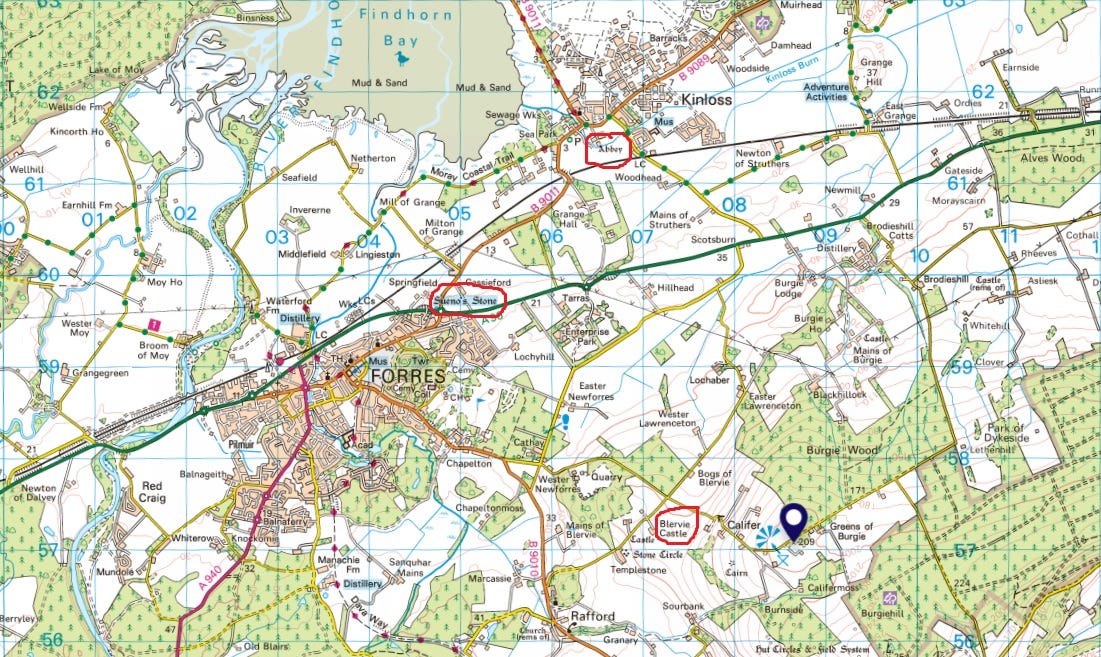

Ulurn/Ulnem/Ulum/Ulrum is reliably identified as Blervie, just south of Forres. But Forres is in Moray, so identifying Nrurím/Uturím with Blervie would mean dismissing the king-list account of Áed being killed in Strathallan; quite a big assumption. Is there any other evidence that might support the idea that Áed was killed in Forres?

Well, there is Alex Woolf’s theory that the branch of the Alpinid dynasty that descended from Áed was based in Moray. Whether Áed himself was based there or whether this northern power base was established in the next generation is unclear. But it at least hints at a reason why Áed might have died in Moray rather than Strathallan.

A forgotten civitas at Forres?

Secondly, there’s the reference to Nrurím/Uturím as a civitas. Only two other places are called civitas in CKA: Scone and Brechin, both with royal connections—the former being a place of secular as well as ecclesiastical power, and the latter as a church endowed by Cináed mac Maelcoluim (d. 995 AD).

Dunkeld, meanwhile, despite being the chief church of southern Pictland, is referred to in CKA as an ecclesia. Are these terms interchangeable, or is there something special about civitas?3

In my last blog I looked at the possibility of Forres—in particular, Sueno’s Stone—being a place of inauguration for the northern branch of the Alpinid dynasty; the branch Woolf sees as being descended from Áed. If that was the case, then Forres could be seen as a northern twin of Scone in terms of function and importance, perhaps meriting the civitas label.

I have to admit, though, that apart from Sueno’s Stone itself, there’s no evidence of a major early medieval secular-ecclesiastical settlement at Forres (or indeed Blervie). But I am becoming gradually more convinced that something of the sort must have existed nearby, perhaps on the site later occupied by Kinloss Abbey.

Persistent connections with tenth-century kings

Lastly, there’s the fact that Forres appears elsewhere in the early sources in connection with the Alpinid kings. As well as claiming that Malcolm mac Domnáill (Malcolm I) was killed at Ulurn/Ulnem/Ulum/Ulrum in 954 AD, some of the king-lists also state that Domnall mac Causantín (Donald I) was killed in Forres in 900, and that Dubh mac Maíl Coluim was killed in Forres in 966.

Even if the first two are just twelfth-century propaganda, they still hint at a link between Forres and the Alpinid dynasty. By the twelfth century Elgin had become the chief place in Moray and the site of the bishop’s seat. So why the emphasis on these kings being murdered in Forres, rather than Elgin, unless there had been something particularly notable about Forres in the ‘old days’?

Admittedly this all feels a lot like clutching at straws, but then so do the other three theories about Nrurím, so I don’t feel too bad about airing my own theory here.

So what have I learned?

I started this blog thinking it would be relatively easy to critique the three Nrurím theories. Certainly neither Chalmers’s nor Hudson’s felt plausible to me, and I thought it might be quite straightforward to explain why.

In fact it turned out to be very difficult, and I’m not sure I’ve done a very good job of it. I’m not a historical linguist, I’ve had one fifteen-minute lecture on palaeography, and I’ve never seen the manuscript of CKA as there’s no digitised version online. So imagining how words like Nrurím might have originally been written, how place-names might have been spelled in the early middle ages, or how they might have got corrupted over time, turns out to be far beyond my present abilities.

It has been enjoyable, though, and a useful exercise for understanding how little I know and how much I still have to learn. Plus I’m quite fond of my Nrurím/Uturím/Ulurm theory, even though it’s probably no more plausible (or provable) than the others. If anyone has any other theories, I’d love to hear them.

References

Anderson, Marjorie O. Kings and Kingship in Early Scotland (1973)

Chalmers, George. Caledonia, Or an Account, Historical and Topographic, of North Britain, from the Most Ancient to the Present Times, Vol. 1 (1807)

Gondek, Meggen. Mapping sculpture and power: symbolic wealth in early medieval Scotland. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 2003

Hudson, Benjamin T. “The Scottish Chronicle.” Scottish Historical Review 77 (2004)

Innes, Thomas. A Critical Essay on the Ancient Inhabitants of the Northern Parts of Britain or Scotland (1729)

People of Medieval Scotland Database

Watson, W.J. The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (1926)

Woolf, Alex. From Pictland to Alba 789-1070 (2007)

I haven’t been able to identify where Chalmers got the information about Giric being mormaer of (presumably) Mar. This doesn’t appear in any of the early sources, so I’m guessing it must come from a later, unreliable source like Hector Boece or George Buchanan.

Chalmers has Nrurin rather than Nrurím because he copied the name not from the manuscript itself but from the appendix of a 1729 essay by Thomas Innes, which contained transcription errors. Given that Inverurie appears as Inuerurin in 1178, Innes’s mistranscription may have given Chalmers more confidence in his theory.

I have Professor Meggen Gondek’s 2003 PhD thesis on symbolic wealth in early medieval Scotland to thank for drawing my attention to the possible nuances of meaning between civitas, ecclesia and other early medieval Latin words for high-status buildings and settlements.

Fascinating stuff as ever! It does seem hard to dismiss the Strathallan thing in the absence of anything more solid though. I guess as with the Strathearn/Culross connection it could potentially be intended politically instead of hydrologically - but it's not going to reach Forres! I wonder if there are any other toponyms that might be brought into play if Anderson's theory that the 'n's could be 'u's were accepted?

The odd thing about Blervie as the potential site of Malcolm's death is that the argument that pulls one way about Forres (ie even if the kings' deaths there are fictional propoganda, Forres must have been an important place to carry that level of symbolism when it was invented) surely goes into reverse for Blervie? If you were going to invent a fictional place of death to score propoganda points, why would you choose somewhere so obscure? Especially one so close to Forres? It feels there must be at least some pretext for such an otherwise random place to be chosen.

As an aside, what's the basis for Elgin being the most important place in Moray by the 12th century? It was obviously a burgh, but then so was Forres; it didn't become the seat of the cathedral until until the 13th century, and the sherrifdoms of Elgin and Forres weren't combined under Elgin until the late 15th century. If anything Inverness would seem to be the dominant centre of secular power in Moray post-Stracathro - it was probably the seat of the Sheriff of Moray mentioned in 1172, and was where the Leges Scocie specified stelen goods in Moray, Ross and Caithness should be taken for dispute.

You have my sympathy for the lack of reliable information that you're running into. It reminds me of the early days of the internet, when there was just enough content to make it tantalizingly easy to expect more...only to run into dead ends. Now I also have sympathy for future researchers who will have to deal with information overload made worse by easy access for the ignorant. I guess the silver lining is that you didn't have to deal with more than 3 implausible theories, lol.

In any case, I am thoroughly enjoying your historical journey. For some reason, I've come to view it as a medieval soap opera, always waiting for you to shine a light on another mysterious circumstance...

Best of luck with your continued research and studies!