Sicut rivulus descendit in Massat: A lost Pictish cultic site?

In which I ponder the significance of a lost river confluence mentioned in a twelfth-century charter of Kinloss Abbey

[Republished 06/11 with updates and corrections]

Long-term readers of this blog may remember that in July last year, I mulled over a twelfth-century land grant to Kinloss Abbey whose geography I found very confusing.

The charter clause defining the original grant of land to the Abbey seems to suggest that at the time of the abbey’s foundation, the Kinloss Burn flowed into the Mosset Burn before both water-courses entered the Moray Firth at Findhorn Bay.

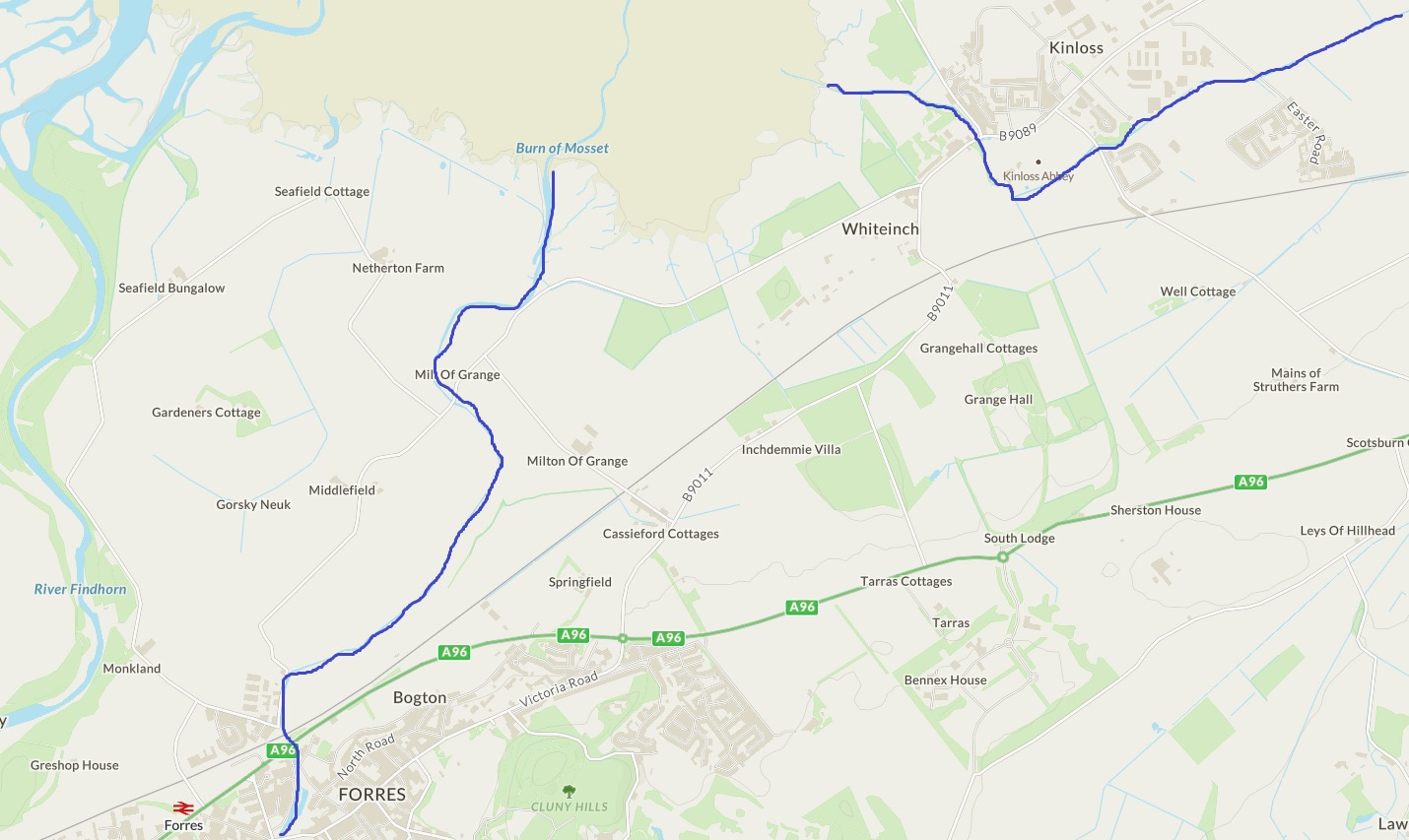

Today, the two burns enter the bay about a kilometre apart (see pic below), although both have been significantly manipulated since the twelfth century.

In this blog I want to think about whether the two burns really did meet in Kinloss—and if so, whether it’s significant that the abbey was founded on or near the site of a now-lost river confluence.

The lost confluence: sicut rivulus descendit in Massat

First, then, the charter in question. Kinloss Abbey was founded by David I in 1150, although no foundation charter survives. It may not even have existed as a written document, as written charters were very rare in Scotland prior to 1150, and this foundation may have followed the older tradition of defining boundaries by perambulation (the donor, the recipient and high-status associates walking around them) and consensus (everyone agreeing that these are the boundaries).

The first written record of the land originally granted to the abbey dates from some time between 1187 and 1203. It’s a protection charter issued by Richard de Lincoln, bishop of Moray, who undertakes to protect the abbot, his monks and their lands from any harassment.

The charter specifies the lands granted to the abbey on its foundation as:

Kynlos et Inuerlochethin per rectas divisas suas. Terram quoque quam ipse Rex David eis perambulavit sicut rivulus descendit in Massat et sicut maresia descendit ad nemus. Et terram super quam Scottie molendinum stabat cum piscarijs et omnibus alijs ad predictam terram pertinentibus. Et terram Eth quam Tvethel tenuit per easdem divisas per quas ipse tenuit. Et unum rete in aqua de Eren. Et boscum de Inche damin.

Which translates to:

Kinloss and Inverlochty by their proper bounds. And the land which King David himself perambulated, as the burn falls into Massat and as the marsh runs down to the wood. And the land on which the Gaelic mill used to stand, with its fishings and all the other things belonging to that land. And the land of Áed which Túathal held, by the bounds by which he held it. And a net in the River Findhorn. And the wood of Inche Damin.

Ignoring the mention of Inverlochty, which is a different place and not relevant to the rest of the description or to this enquiry, what’s interesting to me is the phrase:

Terram quoque quam ipse Rex David eis perambulavit sicut rivulus descendit in Massat et sicut maresia descendit ad nemus.

And the land which king David himself perambulated, as the burn falls into Massat and as the marsh runs down to the wood.

Massat here must surely be the Mosset Burn, which today runs through the west end of Forres before turning north towards Findhorn Bay. And because the charter concerns Kinloss Abbey I presume the unnamed rivulus is the Kinloss Burn, which still runs through the abbey site.

A confluence in the middle of the bay?

What, then, must the waterscape around Kinloss Abbey have looked like in 1150 for the Kinloss Burn to feed into the Mosset Burn? It’s something I puzzled over for a long time, until I came upon a possible answer courtesy of Professor Leif Isaksen of Exeter University (and, like me, another member of the Forres diaspora).

Leif suggested that the confluence didn’t need to be on dry land, and that sicut rivulus descendit in Massat could refer to the point in Findhorn Bay where the two burns meet. Indeed this junction was used as a landmark in later centuries: in 1758 it was included on a detailed map drawn up to settle a dispute over fishing rights in the bay.

Findhorn Bay is tidal, so it may have been possible—if perhaps not very advisable—for David and his co-perambulators to walk to that point at low tide. (Maybe a local reader might be able to confirm whether it’s walkable or not.) Or perhaps they specified it by looking at it from the shore.

Either way, this was my front-running theory until very recently, when I chanced on another, quite intriguing possibility.

An older eastwards course of the Mosset?

I was reading the chapter about Forres kindly given to me by Dr John Barrett, from his forthcoming book on the medieval burghs of Moray entitled The Civilisation of Moray: Burghs in the Landscape and the Landscape of Burghs, when I noticed this very interesting statement:

The market-street of Forres was aligned east-west along the spine of a sandy ridge about 60ft above sea level, with the castle closing the vista at the west end. The Mosset Burn washed the feet of the northern tenements in a course that continued to be a defining feature in eighteenth-century sasines [property records]—long after the burn had been redirected into a more northerly channel. [my emphasis]

This suggests that the Mosset in its original course used to head eastwards towards Kinloss as it ran past Forres, rather than northwards towards Findhorn Bay as it does today. I’ve tried to plot this possible eastwards course in the maps below.

First, here’s an 1832 plan of Forres showing very clearly the outline of the tenements either side of the central market street, in a classic medieval burgh layout. I’ve outlined in blue the Mosset “washing the feet of the northern tenements,” in John Barrett’s words, then heading out east through parts of the Forres hinterland called (in suitably watery fashion) Bogton and Springfield.

[UPDATE: Thanks to Alastair Fraser who has pointed out that the original map I had here couldn’t be right as it had the burn flowing uphill (not the first time I’ve had to be reminded that water doesn’t flow uphill!) and that the Lee Bridge was the original medieval bridge over the Mosset, so the eastwards turn would have to be after it. I’ve put in a new map here with that change made.]

And here’s that course continuing out towards Kinloss, roughly between the B9011 road—which runs along the higher 10m contour—and the Inverness-Aberdeen railway line. [NOTE: Now also updated as per the above.]

And in this next one, I’ve shown how and where it might have met the Kinloss Burn, before the abbey’s monks diverted the burn for water power and sanitation:

An explanation for some puzzling features and place-names

Obviously, this is a lot of speculation on my part, and I’m not in any way a geographer so this may not be how water courses work. But a course and a confluence like this would explain quite a few things that have been puzzling me.

Firstly, and most obviously, it would explain why Bishop Richard’s charter to Kinloss Abbey uses the confluence of the burn and the Mosset as a boundary marker of the original abbey lands. Related to that, it might also help to explain the big shield-shaped enclosure-like feature around the abbey in the centre of this aerial view:

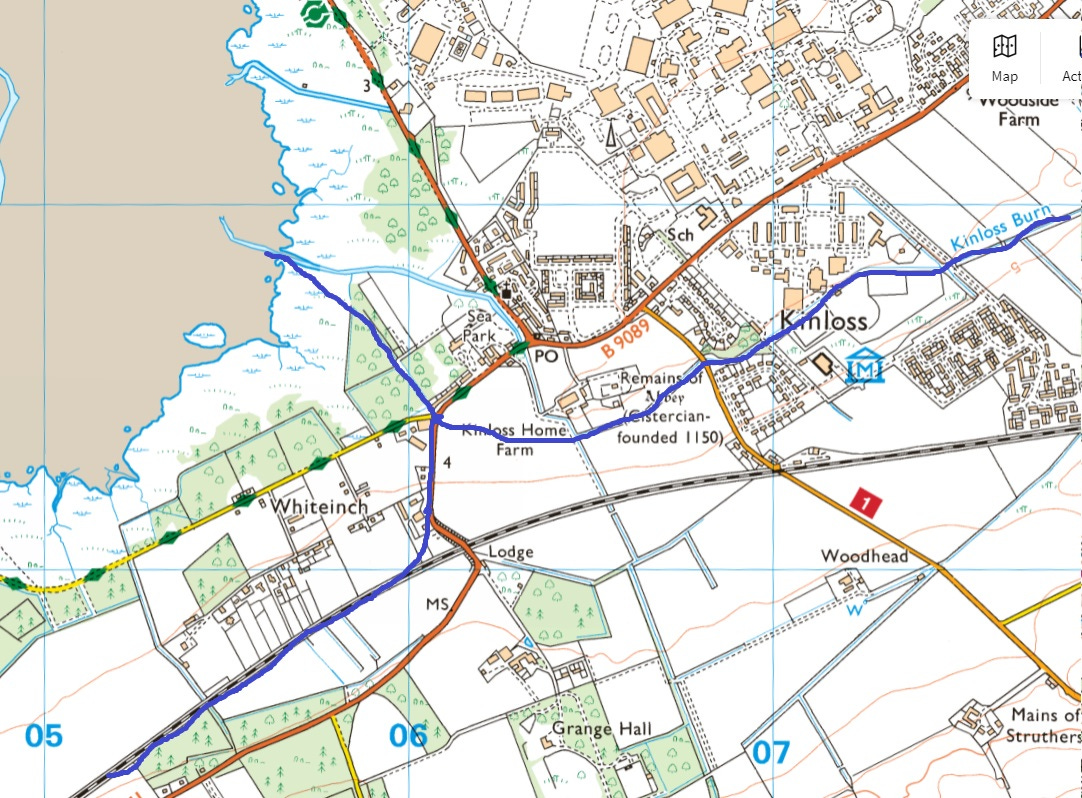

As this feature is too big to be a vallum (ditch) enclosure, yet it seems to encircle the abbey grounds very neatly, I wonder if at least the western side of it represents the old course of the Mosset, which became fossilized as the boundary of the abbey lands after the burn was diverted northwards in Forres. That might explain why the B9011 bends sharply to the left at the Grange Hall lodge and curves around the abbey, rather than continuing straight on into Kinloss: it’s respecting the old burn boundary.

If this is the case, the point where I’m suggesting the rivulus descendit in Massat would form the north-western corner of that boundary—now the junction of the B9011 and the back road from Forres that arrives in Kinloss at Whiteinch (as circled in red below).

A possible explanation for two local place-names

If the Mosset did flow this way towards Kinloss, it might also help to explain a couple of the place-names along its course: Cassieford and Inchdemmie.

Cassieford is just north-east of Forres on the B9011, and appears in the seventeenth century as Calsafuird, i.e. causeway-ford. If we imagine the B9011 as an ancient routeway between Sueno’s Stone and Kinloss (as I’ve done previously), Cassieford might have been a place where it forded the Mosset—though I have to say I can’t immediately make that work on my map reconstruction.

A little further down the road is Inchdemmie, which is plainly the bosco de Inche Damin (wood of Inchdemmie) given in the original grant to Kinloss Abbey. It’s difficult to know exactly where this wood was, but the Gaelic prefix ‘Inch’ means either an island or a water-meadow (haugh in Scots). If we imagine the Mosset flowing by, Inche Damin could have been a water-meadow at its edge.

The same argument could possibly be made for Whiteinch just west of Kinloss, although as an English name with a Gaelic loanword, it’s likely not as old as Inche Damin. And both of these inch names may equally refer to patches of drier land in a boggy landscape rather than river-meadows.

A sacred Pictish pagan site?

Excitingly for me, the possibility of the abbey being founded near a confluence also lends a bit more weight to the idea that it replaced (or took over) an earlier ecclesiastical foundation on this spot. I investigated that idea at length in this blog, but I didn’t take this possible confluence into account.

However, there’s an established theory that the Picts were drawn to river confluences, for which they had a word, aber, which still persists in place-names like Abernethy, Abertarff and Aberfoyle. It also meant river mouth, hence Aberdeen and Arbroath.

In a 1997 paper entitled “Pictish rivers and their confluences,” the place-name scholar W.F.H. Nicolaisen suggests that at least some of these aber-places held sacred meaning for the pagan Picts. He cites Aberdeen as an example of an aber-place at the mouth of two rivers named Devana/Devona (for the Don) and Deva (for the Dee), both meaning ‘goddess,’ and then adds:

[I]t is more than likely that Pictish ‘river worship’ was concentrated on locations at which a smaller tributary joined a larger water-course or at which a river flowed into the sea… Abers could therefore have been regarded as holy ground, a notion which is reinforced not only by references to the ‘purity’ of a river as in Abernethy, or its healing powers as in Arbuthnott, but also by references to a water demon, as in Aberfeldy, or its identification with a bull, as in Abertarff.

Admittedly, the Mosset Burn isn’t a major water-course—the major river in this area is the Findhorn—but perhaps it didn’t need to be. Another Pictish aber-place not far from Kinloss is Cawdor, which appears in a thirteenth-century charter as Abbircaledour (possibly ‘confluence of the hard water’). That may refer to the confluence of the Cawdor Burn and the River Nairn, but the village is actually closer to the smaller confluence of the Cawdor and Riereach burns (see below).

What does this have to do with an early Christian church on the site of Kinloss Abbey? Well, Nicolaisen argues that the sacredness of certain river confluences to the Picts was a factor in the siting of early churches in Pictland:

If, indeed, confluences were cultic places for the Picts who had their ‘nemeta’ [sacred spaces] nearby, then it is not surprising that Christian establishments and places of worship were created close to such pagan locations, and that at least twenty-two of the Scottish Aber names designated, or are still applied to, parishes.

On its own, this is highly tenuous evidence for an earlier Christian church on the Kinloss Abbey site. It’s based on three layers of speculation: a) that there was once a confluence nearby, b) that this confluence was a sacred space for the local pagan Picts, and c) that early Christians founded a church near this sacred space, which was in turn taken over by Cistercians in 1150 to create Kinloss Abbey.

But taken together, the mention of a confluence with the Mosset at or near Kinloss in Bishop Richard’s charter, along with the reference to a bridge at Kinloss in 966 AD in the medieval Scottish king-lists, and the reference to a demolished horizontal mill in Bishop Richard’s charter, give the faintest of hints of an early church site on this spot.

I think a picture is certainly building up, and perhaps before long I’ll be able to scrape together enough fragments of evidence to make this argument properly.

A spanner in the works—or not?

I’ll sign off with a thing I’ve discovered since I started writing this blog, and which may throw a spanner in the works of the speculation above, or it may actually strengthen it—I don’t know yet.

This is a 1309 charter of Robert the Bruce, in which he orders the sheriff and bailies of Forres not to prevent the monks of Kinloss from diverting the Mosset. I don’t have the original Latin, but the translation in the People of Medieval Scotland (POMS) database1 reads:

[King Robert] mandates and firmly orders the sheriff and bailies, in faith and law, that they are not to impede, nor are they to permit any other person to impede, the abbot and convent of Kinloss or their men, so that the monks may be able to dig, to drag, and redirect the burn of Mosset from the middle of the king’s land as far as their house of Kinloss, which they have from the gift of the king’s predecessors. [my emphasis]

If the Mosset already flowed near the abbey in 1150, as Bishop Richard’s charter seems to say, what does it mean that in 1309 the monks were allowed to divert it “from the middle of the king’s land” to the abbey? Was this just confirmation of an earlier right they had to the burn? Had the burgesses of Forres been threatening to divert it away from Kinloss—as they ended up doing later anyway?

I’ve no immediate answers, but it looks like this will be something I need to investigate at some point. In the meantime, if anyone has any thoughts I’d be glad to hear them.

References

Barrett, John R. The Civilisation of Moray: Burghs in the Landscape and the Landscape of Burghs (forthcoming)

Innes, Cosmo (ed.) Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis (1837)

May, Peter. A Survey of the River Findhorn with the fishing places &c (1758)

Nicolaisen, W.F.H. ‘On Pictish Rivers and Their Confluences,’ in The Worm, The Germ and The Thorn: Pictish and related studies presented to Isabel Henderson (1997)

People of Medieval Scotland (POMS) online database

Stuart, John (ed.) Records of the Monastery of Kinloss with Illustrated Documents (1872)

The POMS database seems to be offline at the time of writing.

Hi Fiona

As thought provoking as ever.

Some thoughts on your conjectural hydrology…..

The Lea Bridge over the Mosset was the primary crossing point over the burn throughout the medieval period and into the modern. This was on the direct route to the crossing of the Findhorn at Waterford.

That’s not to say that it didn’t turn east beyond that point.

Prior to the building of the bypass, Councillors Walk i.e. the traditional town boundaries ran along that line. I always wondered why that was the boundary as there was little or no geographical feature to define it, but if the Mosset Burn ran there…..

BTW your line on the 1832 map is definitely off - you have the burn flowing uphill! Back Street is now what is North St and quite a stiff climb up from the banks of the Mosset. It’s more likely to have followed the line followed by the railway today.

On Cassieford, I think the OS map is misleading. It labels the farm which is uphill and on the wrong side of the Kinloss road. However, when I was growing up in the area, Cassieford was applied to the small settlement on the other side of the Kinloss road on the downslope to where the burn would be in your conjecture. I have to say I think this and the Inchdemmie name are quite indicative - I grew up wondering where the ford in Cassieford actually was

Finally, on the RtB charter, could this be reflecting that the burgesses of Forres had already diverted the burn and Kinloss Abbey were looking to re-establish the original course? Quite often such intervention by authority only came after the locals had taken the law (and property boundaries) into their own hands.

Keep up the good work

Had a bit of trouble signing in today (although it's been fine in the past) & it wouldn't let me post a comment WITHOUT signing in, but it seems to have worked now! I just wanted to say: this is all as fascinating as ever, and I think Inchdemmie is a great place name! (Not as good as Findhorn obv, but still fun.) I hope it turns out your river went where you hope it did - or, at least, that you find proof one way or the other!