'Earn' place-names in Moray: Early Irish colonies?

In which I examine a theory that sees 'earn' place-names as indicators of early Gaelic settlement on the Moray Firth

Long-term readers (hello!) may remember that last year I mulled the idea that Sueno’s Stone near Forres might commemorate a victory in 904 AD of Constantine II of Alba over a viking army who had ravaged “Dunkeld and all Albania” in the previous year.

The cornerstone of this idea was that the 10th-century Chronicle of the Kings of Alba notes that this battle took place in “Sraith Herenn.” This is usually taken to mean Strathearn, the valley of the Earn in Perthshire.

But as Alex Woolf pointed out in 2006, there is more than one ‘Sraith Herenn’ in the Pictish heartlands. The river Findhorn was also once known as the Earn. So in my blog, I toyed with the idea of a location on the Findhorn for the battle of Sraith Herenn.

A district name meaning ‘Ireland’?

In researching that blog, I re-encountered an odd theory that I’m going to try to make sense of in this one. It was first aired in 1926 by the place-name scholar W.J. Watson, who proposed that Sraith Herenn has less to do with any river called Earn, and more to do with Ériu or Éire, the island of Ireland.

It’s quite a complex theory, and I’ll try my best to untangle it without boring anyone.

First, here’s Watson, writing in The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland about Strathearn in Perthshire:

There can be no doubt that the name Éire was used as a district name in the parts of Britain where the Gael settled. I believe that Strathearn means ‘Ireland’s Strath,’ not ‘Strath of the River Earn,’ and that Loch Earn (Loch Éireann) means ‘Ireland’s Loch’.

Watson had come to this conclusion in three ways. Firstly, he noted that other places in Britain have names that mean ‘Ireland’ or ‘Place of the Gael’ – like Iwerddon and Dolwyddelan in north Wales.

Secondly, he identified place-names that include an element like earn but which aren’t near the river Earn. One such place is a Raterne mentioned in a charter of 1488, which he parsed as Ráth Éireann, ‘Ireland’s Fort,’ and identified as modern-day Rottearns in Strathallan.

Lastly, he noted a passage from an 8th-century tract in which Culross (which is definitely not in the strath of the Earn) is mentioned as being in Strath Erenn. He concluded, as we saw above, that Sraith Herenn must have been the name of a much wider district than (just) the area around the river Earn (see map below).

‘New Irelands’ on the Moray Firth

More pertinently for this blog, Watson saw a similar pattern along the southern shore of the Moray Firth. He identified three separate northern ‘districts’ that seemed to be called Éireann for ‘Ireland’: one in Nairnshire, one in Moray, and one in Aberdeenshire.

For simplicity I’m going to leave the last one, around the River Deveron (which Watson sees as Dubh-Éireann) for another time, and just focus on the first two.

‘New Ireland’ in Nairnshire: Auldearn

The Nairnshire ‘district’ of Éireann is Auldearn and its environs. Watson’s source for this is a land grant of 1140 from David I to the priory of Urquhart, of “Pethenach near Eren, and the shielings of Fathenachten.” He deduces that Pethenach is Penick and Fathenachten is Fornighty, and concludes that:

This Erin [sic] was therefore in Nairnshire, and appears to be the old name for Auldearn parish. In any case it is the name of a district, and Allt Éireann, Auldearn, means ‘Ireland’s burn.’

I have to say that Watson’s thinking here isn’t terribly clear to me. From the land grant he quotes, Eren seems to be the name of a settlement, as Pethenach is described as being ‘near’ Eren, not ‘in’ Eren. To me this doesn’t suggest that Eren was a ‘district’ but a settlement: in fact the early medieval settlement that I looked at in my last blog. It may even be part of the next ‘district’ that he notes, which I’ll look at now.

‘New Ireland’ in Moray: around the Findhorn

Watson’s second northern Éireann is around the lower reaches of the river Findhorn in Moray. Here, he seems to suggest that both the river and a number of places near it were (re-)named in honour of Ireland by the area’s early Gaelic-speaking settlers.

The etymology of ‘Findhorn,’ he says, is Fionn-Éire, meaning ‘white Ireland,’ which “doubtless refers to the white sands of the estuary.” He seems to be saying that the name ‘Findhorn’ was only applied to the estuary area of Findhorn Bay, with the rest of the river simply being called Éire/Earn/Eireann.

As well as the estuary itself, Watson cites a few place-names nearby that he believes support his theory. One is Invereren, a place that no longer exists,1 but which appears in early charters. Watson believes this was the old village of Findhorn, near the old mouth of the river. It was washed away in 1702 when the Findhorn dramatically changed course at its mouth, and nothing now remains of it.

In addition to Invereren, he says:

The names Cullerne and Earnhill, near the mouth of the Findhorn, meaning ‘nook of Eren’ and ‘hill of Eren,’ are further in favour of the area having been a district… Near Dulsie Bridge is a large fort called Dún Éireann, Ireland’s fort, a name which may indicate that the district extended well inland.

Later, he tentatively suggests one more possibility, evoking another name for Ireland:

…another name for Ireland is Fàl, and we have Dunfàil, Dunphail, near Forres...

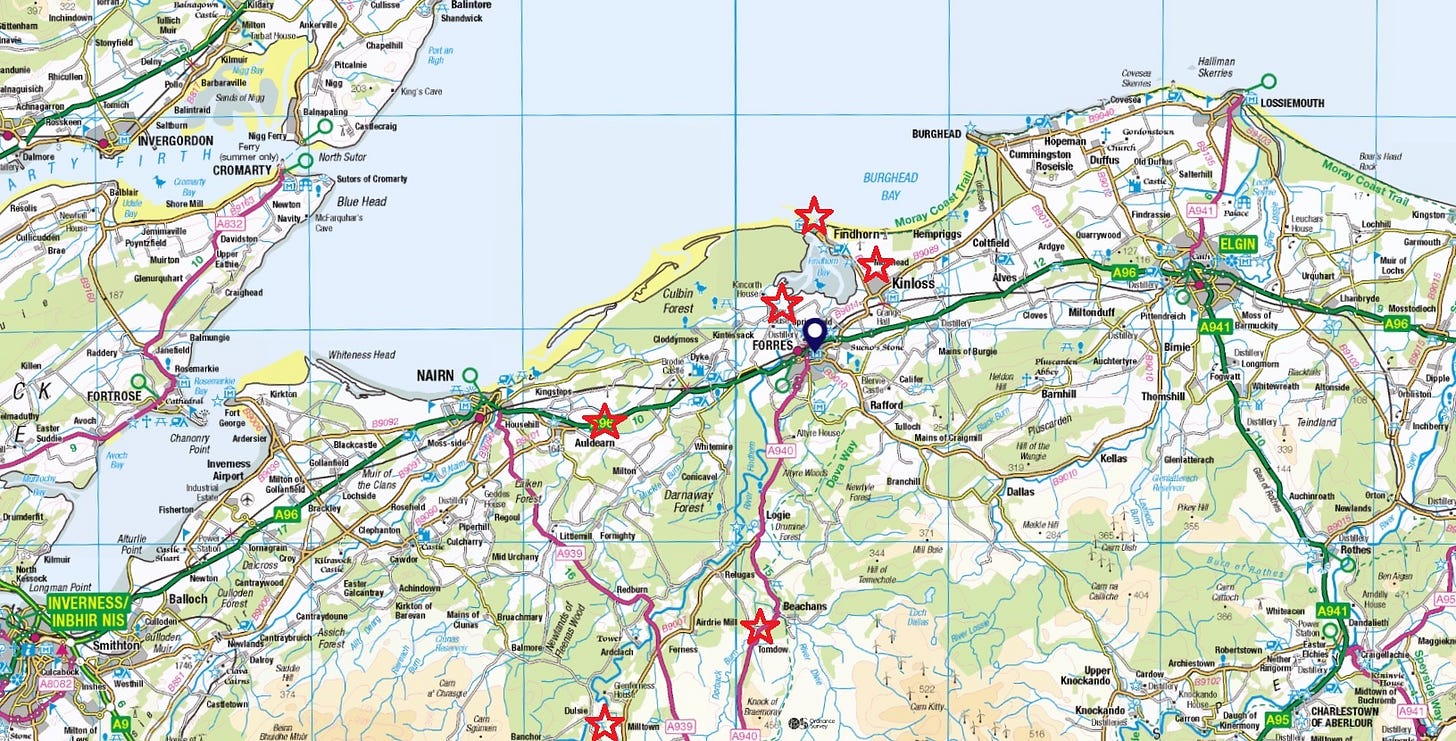

I’ve plotted all these places on the map below. Running from north to south, the red stars indicate Invereren, Cullerne, Earnhill, Auldearn, Dunphail and Dunearn.

River names, rather than ‘Ireland’ names?

There’s nothing inherently strange about places being named after other places. It’s a common strategy deployed by colonising forces to stamp their perceived ownership and authority on to the newly-occupied land.

We also know that Gaelic speakers—who originated in Ireland—must have colonised this part of Scotland during the early Middle Ages, as their language had replaced the Pictish language by the 12th century when we start to get (still-sparse) documentary sources for Moray.

But that said, something feels odd about so much ‘New Ireland’ naming in a small geographical area—especially as I’ve only mentioned a subset of the names Watson highlighted, to avoid over-complicating this blog. (His full list includes Banff, Boyndie, Deveron and Elgin, as well as Atholl further south.)

Indeed, when other toponymists have commented on Watson’s theory, it’s often been with scepticism. In a chapter of Moray: Province and People (1993) called Names in the Landscape of the Moray Firth, leading place-name scholar W.F.H. Nicolaisen noted:

If [Watson’s] interpretations are right this would indeed be a remarkable accumulation of names reinforcing each other in their direct links with the country from which the settlers or their ancestors had ultimately come.

However, he went on to say:

I have been studying river names for almost forty years now, and instinct tells me they do not behave in this way. For the second part of Findhorn and Auldearn and the related Deveron, an original river name is more likely, and much points in this direction, i.e. of the -horn, -earn and -eron representing ancient river names meaning ‘flowing water’.

In other words, Nicolaisen believes the Auldearn Burn and the Findhorn were already called something like ‘Earn’ when Gaelic speakers first settled in Moray, and the settlers may simply have added prefixes (allt-, fionn-) in their own language.

Support for the Auldearn theory

Revisiting the debate in 2010, however, Professor Thomas Clancy (Glasgow University) thought Watson may have been on to something—at least regarding Auldearn.

In a book chapter entitled Atholl, Banff, Earn and Elgin: New Irelands in the East Revisited, he noted that:

Auldearn as a form first appears in the fourteenth century, by which time we may be dealing with the Scots auld here, the contrast perhaps being with the now-lost Invereren, at the mouth of the Findhorn. The significance here is that Auldearn therefore ceases to be another example of a hydronym and Watson’s case becomes somewhat stronger.

So Clancy is suggesting that Auldearn’s original name of Eren referred not to the burn but to the settlement, and thus could more plausibly have been named Éireann for Ireland.

As there’s some evidence for an early Columban church in Auldearn, which could well have been an outpost of the Gaelic-speaking monastery of Iona, an ‘Ireland’ name for Auldearn starts to seem less far-fetched.

But what about the Findhorn?

Clancy is less convinced about the Findhorn. He agrees with Nicolaisen that ‘Earn’ (or similar) was probably what the river was already called when Gaelic speakers settled in Moray:

Watson makes good use of some other names, such as Cullerne and Earnhill, on the lower Findhorn, and Dunearn hillfort on the upper Findhorn, as indicating the extent of the district he thought of as Eren (< Ériu). But… these could all be names derived from their proximity to [a river] named ‘Eren’.

However, he’s reluctant to dismiss Watson’s theory out of hand—especially given that the Perthshire Strathearn definitely seems to refer to a wider region. In which case, he says, perhaps Watson’s most tentative suggestion was on the right lines after all:

It may be worth giving a cameo appearance to the other Ireland name, Fál. It is in the north-east, some eight miles south of Forres, that we find Dunphail (< Dún Fáil?) – is this another Ireland name? Watson had his doubts, but the proximity to some of the others we are discussing is interesting.

Two more earn names to consider

At this point I’d like to throw a couple of other names into the mix that neither Watson, Nicolaisen nor Clancy seem to have considered, and which may lend more weight to Watson’s theory.

I’ve noted the first one before: it’s Earnside near Alves, which isn’t beside the Findhorn (or indeed any flowing water) but still has an ‘earn’ name. Its second element is Scots rather than Gaelic, and it doesn’t seem to be attested before the 15th century—when it was the site of a castle of the Comyn family—but it could still recall an older name.

More intriguing is a place called in some high medieval sources Ulern or Vlerin. This place is securely attested in a charter of Alexander II from 1221 detailing a land grant to Kinloss Abbey. From the description in that charter, it seems to be the estate now known as Blervie, south-east of Forres. Perhaps significantly, versions F and I of the medieval Scottish king-list say that Ulern is where Malcolm I of Alba died in 954 AD.

Adding Earnside and Ulern to the map produces this:

Even if we don’t believe that these earn/ern/erin names mean ‘Ireland,’ it’s still notable how many of them are clustered around Forres. And even if some of them do refer to the river Findhorn, not all of them can be explained that way: Auldearn, Ulern and Earnside aren’t near that river.

A possible explanation from Menteith…

So what (if anything) could be going on here? For a moment, I thought I had an answer. When I mentioned my research for this blog on Twitter, Dr Murray Cook recommended I read the PhD thesis of Dr Peter McNiven, who’d been looking at the Gaelic place-name element earrann—meaning a portion or share—in the medieval earldom of Menteith in central Scotland.

McNiven’s research showed that this element designates a piece of arable land belonging to an ecclesiastical landowner, and which in Menteith and Galloway has usually been anglicised to Arn or Ern. He gives Arnprior, Arnclerich, Ernfillan and Chapelerne as examples. Professor Richard Oram (Stirling University) has added that in Galloway it appears to refer to assarted land, i.e. land reclaimed from waste to create arable.

I may well be wrong—please do comment if you have any thoughts!—but this doesn’t seem to be what’s going on with these Nairnshire and Moray ‘earn’ names. None, except possibly Auldearn, seem to be associated with any ecclesiastical foundation (although this has reminded me that one day I’m going to look for evidence of an older monastery pre-dating Kinloss Abbey, founded in 1150).

There’s also the fact that earrann seems to become Arn in Menteith and Galloway, whereas I don’t have any ‘Arn’ names at all. Plus most of these northern earn places are unlikely to have been assarts, since (and as McNiven also suggests for Menteith), the low-lying area around Auldearn, Forres, Kinloss and Alves was surely already productive arable land when Gaelic speakers arrived.

…and a much more speculative explanation from me

One other very tentative explanation occurs to me. Historians Neil McGuigan and Alex Woolf have both proposed that Moray was the home base of a branch of the Gaelic-speaking royal dynasty descended from Scotland’s first Gaelic king, Cináed mac Ailpín (r. 842-858).

They disagree on which branch, however. McGuigan has Moray as the base of Clann Causantín, the descendants of Cináed’s son Causantín I (r. 862-877). Woolf thinks it was the base of Clann Aeda, the descendants of Cináed’s other son Aed I (r. 877-878). The other branch, they agree, had its power base somewhere south of the Mounth.

Records show that throughout the 10th century, the over-kingship of Alba alternated between a king drawn from Clann Causantin and one drawn from Clann Aeda. In Woolf and McGuigan’s conception, this means Alpinid kings were drawn alternately from Moray and from a base south of the Mounth.

Here below is Neil McGuigan’s table of the alternating kings and their attested places of death. (Note that McGuigan doesn’t cite Ulern as a possible place of death for Máel Coluim mac Domnaill, even though it appears as such in two of the king-lists. See this blog for why.)

This is the same kind of succession as was practised in Ireland in the early Middle Ages, and there’s evidence that the Gaelic kings of Alba looked heavily to Ireland as a model for many aspects of kingship. Causantín and Aed’s sister, Mael Muire, married two consecutive high-kings of Ireland, and Woolf suggests that Causantín’s son Domnall and Aed’s son Causantín—in the second row of the table above—may have been brought up in Ireland by their aunt.2

Is it possible, then, that the faint references to ‘Ireland’ that seem to survive in ‘earn’ names around Forres denoted territory belonging to this northern branch of the Alpinid dynasty? There’s no documentary evidence for where they were based, but to me it feels significant that the only Moray place-names that appear in the record for the 10th century are Forres, Kinloss and Ulern, and all of them are mentioned in connection with the deaths of three kings of Alba, all from Clann Causantín.

If you can bear one final bit of speculation, if this rash of ‘Ireland’ names in Moray and Nairnshire indicate the core territory of one branch of the ruling Alpinid dynasty, then Sueno’s Stone, which sits right at the heart of this territory, is persistently dated to the ninth or tenth century, and whose Irish stylistic parallels are often remarked upon, may also be connected with that branch of the dynasty.

Whether it commemorates a battle against the vikings, won in 904 AD by Causantín mac Aeda in the heart of this northern Sraith Herenn, is more speculative still.

References

Brichan, J.B. Notice of a Curious Boundary of Part of the Lands of Burgie, Near Forres, in a Charter of King Alexander II, 1221 (1859)

Clancy, T.O. Atholl, Banff, Earn and Elgin: ‘New Irelands’ in the East Revisited (2010)

McGuigan, N. Mael Coluim III ‘Canmore’: An Eleventh-Century Scottish King (2021)

McNiven, P. Gaelic place-names and the social history of Gaelic speakers in medieval Menteith (2011)

Nicolaisen, W.F.H., Scottish Place-Names (1973)

Nicolaisen, W.F.H. Names in the Landscape of the Moray Firth (1993)

Watson, W.J. The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland (1926)

Woolf, A. Dún Nechtain, Fortriu and the Geography of the Picts (2006)

Woolf, A. From Pictland to Alba 789 to 1070 (2007)

There is a house named Invererne to the north of Forres, but this estate appears on 16th and 18th century maps as Tannachy/Tannachie, so its present name must be modern.

Although Woolf recently said on the Scotichronicast podcast that he’s not sure he believes this any more.

The School of Scottish Studies has a recording of the place name Srath h-Eirinn spoken by one of the last speakers of Gaelic from near Tomatin. This is part of the Gaelic Linguistic Survey.

Next question, was there then an early incursion of Irish-identifying people up the Great Glen to this inner Moray estuary? I suspect the answer is quite nuanced. The Great Glen has always been a major route from the west to the east, and it perhaps isn’t the divider of east/west Dalriatans/Picts that tends to be regarded today. At the dawn of history we see pretty clear evidence that the Caledones held both ends (and the middle 😊 ) of the Great Glen. And that is also attested by the use of the boar symbol from Inverness down to Dunadd. Yes I know people try to say the boar was stamped there by invading Picts in the 8th/9th centuries, but it fits better within its mythological context as the boar that rakes the great ditches across the land, bringing into the world all sorts of creatures good and bad. And we now have a growing body of early CI symbols that can be dated to prior to the sudden breakdown c. 200 AD, including the dating of Culduthel beside the Knocknagael boar stone. And let’s not forget that Pictland too, or groups that identified as Pictish, held territory in the west, it goes both ways, over many many centuries. OK, I think what I’m trying to say here is that there probably has always been steady movement up and down the Great Glen, people came and went, traded and married, and no doubt self-identified according to prevailing winds, so perhaps it shouldn’t be a surprise to find names that look ‘Irish’ at both ends. But in the end, I’d say the naming likely dates from the 3rd-6th centuries?